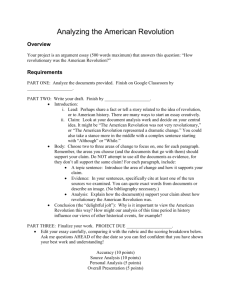

The Revolution of Everyday Life

advertisement