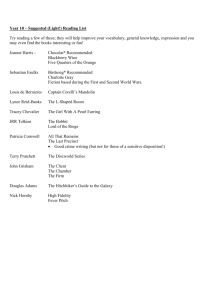

Reaper Man

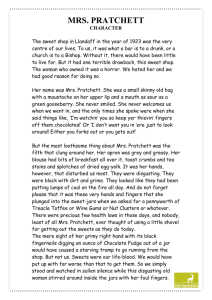

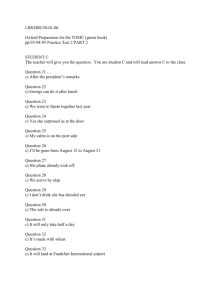

advertisement