222-674-1-RV - ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry

advertisement

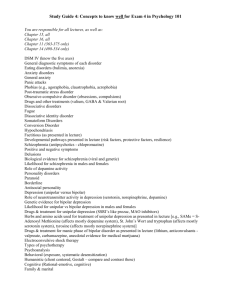

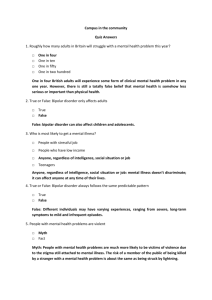

A clinical study of various diagnostic classification systems in bipolar spectrum disorders : especially rare forms. Abstract Objective: There has been a dearth in data as to which system of classification stands most efficient in detecting and diagnosing bipolar spectrum disorders clinically and this needed to be researched. The aim of the study was to compare various new diagnostic classification systems (Jules Angst classification and Akiskal’s classification) in detecting/diagnosing bipolar spectrum disorders especially rare forms) with most widely used methods of classifications like DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10. Methods: This was a cross sectional study of 80 patients clinically suffering from bipolar mood disorder attending the psychiatry outpatient department or those admitted in the psychiatry wards in whom four diagnostic classification systems were compared. Results: All the 59 patients with classic bipolar symptoms were diagnosed by the four diagnostic classification systems. DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 classification classified all the 21 patients of less common forms of bipolar disorder into some or the other category. Akiskal’s classification classified 19 out of 21 patients (90.48%). Jules Angst’s classification classified only 4 of the 21 (19.04%) patients of the less common forms of bipolar disorder. Conclusions: All the diagnostic systems are equally good while classifying patients with classic bipolar symptoms. DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 proved to be the most efficient in classifying less common forms of bipolar disorder. Jules Angst classification lacks diagnostic subcategories like schizoaffective disorder; substance induced mood disorder and dementia with psychotic features, whereas Akiskal’s classification lacks subcategories for cyclothymia. Keywords : Bipolar disorder, diagnosis, DSM-IV-TR, ICD-10, Jules Angst’s classification, Akiskal’s classification LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED BP I – Bipolar I BP II – Bipolar II UP – Unipolar BP – Bipolar BMD – Bipolar Mood Disorder BPAD – Bipolar Affective Disorder BMD-NOS – Bipolar Mood Disorder – not otherwise specified 1 Introduction The concept of bipolar spectrum disorders has evolved over the last few years as propounded by Akiskal and Jules Angst and claims to be more efficient in detecting even rare and less common forms of bipolar disorders [1]. However, there has been no published data quantifying the claim. There has been a dearth of data as to which system of classification stands most efficient in detecting and diagnosing bipolar spectrum disorders clinically. This study was conducted in a municipal general hospital in Mumbai to compare various diagnostic classification systems in detecting/diagnosing bipolar disorders (especially rare forms). Methodology This was a cross sectional study conducted by the department of psychiatry in a tertiary care municipal teaching hospital. The patients were recruited from the psychiatry ward and the outpatient department of the hospital. The sample consisted of 80 patients clinically suffering from bipolar mood disorder attending the psychiatry outpatient department or those admitted in the psychiatry wards. The patients were interviewed in detail with their relatives and enrolled in the study if they satisfied the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were- 1) Patients of either sex and of any age with their relatives willing to participate in the study by signing an informed consent form; 2) Patients with symptoms and history suggestive of a diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder; 3) Patients with adequate and reliable objective data. The exclusion criteria were- 1) Patients lacking reliable objective data; 2) Patients having diagnosis of any other medical disorder likely to alter the clinical course of psychiatric illness; 3) Patients not suitable for the study for any other reason as per the discretion of the investigator. A special proforma was prepared to collect the socio-demographic data, clinical profile of the patient, phenomenology, total duration and details of course of psychiatric illness etc. The other materials used for the assessment of patients included- The Jules Angst’s classification for bipolar spectrum disorders, Akiskals classification for bipolar spectrum disorders, DSM-IV TR and ICD-10. The patients and/or relatives were explained the nature of the study. A written informed consent was taken from the patient and/or relatives. Patients with their relatives were then interviewed using the special proforma and relevant data was collected for the individual case. A complete retrospective and current evaluation of the case histories was done and an attempt to classify each case with different diagnostic systems for bipolar disorders (viz. DSM-IV-TR, ICD-10, Akiskal’s and Jules Angst classification) was made. A study of the phenomenological aspects of the disorder and a comparative study of these classifications was then done. All the 80 patients were divided into two groups according to the symptoms and compared with various diagnostic systems.1) Classic Bipolar Group: Patients having discrete episodes of mania/s and patients having episodes of mania and depression in the course of their illness. 2) Others Group (less common forms of bipolar disorders): patients with episodes of hypomania, hypomania and mild depression, substance induced mood symptoms etc. Written approval for the study was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. Results The mean age of patients with classic bipolar disorder was 35 years (range of 16-65 years) while it was 44 years ((with a range of 23-80 years) in patients with less 2 common forms of bipolar disorder. Majority of the patients were male (72.5 %) in the study (Table 1). All the 59 patients with classic bipolar symptoms were diagnosed by the four diagnostic classification systems. Thirty three (33/59) patients with classic bipolar symptoms were diagnosed as Bipolar-I with psychotic features by Jules Angst classification. All the 59 patients were diagnosed as Bipolar-I by Akiskal’s classification. Of the 59 patients with classic bipolar symptoms, 50 were diagnosed as Bipolar Mood Disorder – I (BMD-I) mania by DSM-IV-TR and 21were diagnosed as Bipolar Affective Disorder (BPAD) manic without psychotic symptoms by ICD-10. as BMD-I in DSM-IV-TR, BPAD in ICD-10 and Bipolar-1 in Jules Angst and Akiskal’s classification. Findings in the table below reveal that all the diagnostic systems are equally good in classifying patients with classic bipolar symptoms (Table 2). Thirteen (13/21) patients with persistent psychotic features and intermittent affective symptoms formed the largest proportion (61.91%) in the group of the less common forms of Bipolar disorders. Akiskal classified them as Bipolar-1/2 while DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 diagnosed them as Schizoaffective disorder. Jules Angst classification was deficient of any sub category for patients with such symptoms and hence these were left undiagnosed (Table 3). One patient with recurrent episodes of hypomania and mild depressions was diagnosed as having Cyclothymic disorder in the Jules Angst classification, DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 classification while the same remained undiagnosed in Akiskal’s classification as it does not mention any subcategory for such patients. One patient who had affective symptoms associated with use of substance was diagnosed as having Bipolar-III ½ in Akiskal classification, as Substance induced mood disorder In DSM-IV-TR and Persistent mood/affective disorder-unspecified in ICD-10. Jules Angst classification lacked any such category and hence the patient remained undiagnosed. Two patients with dementia having affective symptoms were diagnosed as Bipolar-6 in Akiskal’s classification, as Bipolar Mood Disorder – not otherwise specified (BMD-NOS) in DSM-IV-TR and as Unspecified affective disorders in ICD-10. These patients missed the diagnosis in Jules Angst classification. A patient with persistent hypomanic symptoms and intermittent psychotic symptoms was diagnosed as BMD-NOS in DSM-IV-TR and Unspecified affective disorders in ICD-10, while it remained undiagnosed in the Jules Angst and Akiskal’s classification. Overall, as far as diagnosing 21 bipolar patients of the less common forms was concerned the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 proved to be the most efficient as they classified all the 21 patients as bipolar disorders belonging to some or the other category. Akiskal’s classification based on the concept of bipolar spectrum classified 19 out of 21 patients (90.48%). Jules Angst’s classification classified only 4 of the 21 (19.04%) patients of the less common forms of bipolar disorder. All the 80 patients in the study were classified by DSM-IV-TR classification and ICD-10 classification. Jules Angst classification classified 63 (78.75%) while Akiskals classification classified 78 (97.50 %) of the 80 patients included in the study. Seventeen (21.25 %) patients did not receive any diagnosis by Jules Angst classification while 2 (2.50%) patients did not receive any diagnosis by Akiskals classification (Table 4). Schizoaffective disorder was the most common diagnosis (13 patients) which was not classifiable by Jules Angst classification besides substance induced mood disorder (1 patient), dementia with affective features (2 patients) and BMD-NOS/Unspecified affective disorders (1 patient). Akiskal’s classification could not classify 1 patient of cyclothymia and 1patient of BMD-NOS / Unspecified affective disorders (Table 5). 3 Discussion The organization of the mood disorders in our current diagnostic system tends to confound polarity and cyclicity, negatively impacting clinical, genetic, and pharmacological research. Thus, in clinical research on unipolar-bipolar differences, the two groups are rarely matched for cyclicity [2]. The diagnosis of hypomania poses further problems. First, there is a growing movement to simply lower the admittedly arbitrary time criterion for hypomania. Second, symptoms of mood elevation may not be severe enough to satisfy the DSM–IV checklist, yet they are still recorded in patient interviews. Third, the term ‘hypomania’ is misused widely to describe mania itself. None of this would matter greatly if the distinction between bipolar and unipolar disorders had no implication for treatment. However, authors have found that antidepressants were used earlier and more frequently than mood stabilizers in patients with bipolar II disorder, and that almost a quarter of patients experienced a new or worsening rapid-cycling course attributable to antidepressant prescription [3]. The two-dimensional bipolar spectrum described by Angst comprises a continuum of severity from normal to psychotic and a continuum from depression, via three bipolar subgroups to mania. This combination of dimensional and categorical principles for classifying mood disorders may help alleviate the problems of under diagnosis and under treatment of bipolar disorders. Two-dimensional mood/affective spectrum (does not include schizoaffective disorder, as a transition to the schizophrenic spectrum). The precise relationship of personality disorders to the disease spectra is uncertain and an unsolved general problem of psychiatric classification. BP-I (-II), bipolar-I disorder type I (II); D, major depression, d, minor depression; M, mania; m, hypomania; MDD, major depressive disorder; RBD, recurrent brief depression; symptoms [4]. Physicians inevitably encounter patients with bipolar disorders, often when the patient is depressed. For most of these patients, the attendant elevations in mood fall short of mania. Such milder periods of expansive mood, hypo manias, may go unrecognized unless the physician specifically queries the patient to uncover them. In addition, patients with bipolar disorders often manifest other distinctive characteristics. An understanding of these hints of bipolarity is helpful to clinicians treating depressive illness. Patients with bipolar disorders are at risk for treatment complications caused by the administration of antidepressants without the concurrent use of mood stabilizers, such as lithium carbonate, Valproate sodium, and Carbamazepine. Such complications include exacerbation of hypomania or mania, induction of refractory states, and, perhaps, rapid cycling or mixed states [5]. Kraepelin’s view from the previous turn of the century of affective disorders, i.e., comprising both UP (unipolar depressive disorders) and BP (bipolar disorder or the bipolar disorder spectrum) in current terminology, as a broad panorama of variants of manic-depressive disorders, finds support in modern research [6-11]. It is above all the discoveries of the high prevalence of bipolar II (BP II) and other bipolar spectrum disorders [12-14] and the new knowledge of highly frequent conversion of unipolar (UP) to bipolar (BP) [11, 15] that lend support to Kraepelin’s view. There is, however, also support for the view that UP and BP can be conceived of as partially separate categories [6]. The courses of BP and UP differ in terms of younger debut age and more frequent recurrences of the former [15]. In terms of courses and symptoms, BP II is to a much higher degree a depressive disorder than bipolar I (BP I), in that periods of manifest or subsyndromal depression relative to periods of hypomania/mania are more than 10 times longer in BP II than in BP I [16]. Symptomatically BP II and UP are different in that hypomanic episodes occur only in the former, while BP II differs 4 symptomatically from BP I in that only hypomania, not mania and often psychosis occurs. The age of onset of bipolar disorder varies greatly. The age range for both bipolar I and bipolar II is from childhood to 50 years, with a mean age of approximately 21 years. Most cases commence when individuals are aged 15-19 years. The second most frequent age range of onset is 20-24 years. Some patients diagnosed with recurrent major depression may indeed have bipolar disorder and go on to develop their first manic episode when older than 50 years. They may have a family history of bipolar disorder. However, for most patients, the onset of mania in people older than 50 years should lead to an investigation for medical or neurologic disorders such as cerebrovascular disease [17]. Detection and diagnosis of bipolarity in mood disorders assumes prime importance for the sake of appropriate treatment to be initiated right from the start of the illness. The most widely used classifications for diagnoses; the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 have always been under the critical eye of investigators for their ability to pick up bipolarities and clinical applicability in diagnosing bipolar disorders. Akiskal’s concept of the bipolar spectrum proposes to be a better system of diagnoses to classify bipolar disorders especially the rarer forms. Similarly the concept of bipolar spectrum given by Jules Angst claims the same. There has been a lack of evidence to quantify the claims. A dearth in data to evaluate the conceptual and phenomenological validity of the bipolar spectrum has always been felt. The data for a comparison of available systems of diagnoses to identify, diagnose and classify bipolar disorders has been scarce. Literature on studies testing the conceptual validity of the bipolar spectrum by a comparison with currently used diagnostic systems like the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 to diagnose and classify bipolar systems clinically was found to be deficient. Conclusions All the diagnostic systems are equally good while classifying patients with classic bipolar symptoms. However, in case of the less common forms of bipolar disorder, a marked difference was observed among the diagnostic systems in their efficacy to clinically diagnose bipolar disorder. Patients with rare and new forms of bipolar symptoms can be included in categories like BMD-NOS and Unspecified affective disorders (in DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 respectively), so that they do not miss a diagnosis of bipolar disorder for the lack of any particular diagnostic subcategories. Such subcategories are therefore useful and recommended in classifications like Akiskal and Jules Angst to make them clinically more efficient as diagnostic systems for bipolar disorders. REFERENCES 1. Phillips ML, Vieta E. Identifying functional neuroimaging biomarkers of bipolar disorder : toward DSM V. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33(4): 893-904. 2. Goodwin FK. The evolution of the concept of bipolar disorder. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2008; 36(1): 40-2. 3. Bhagwagar Z, Goodwin GM. Bipolar spectrum disorders : an epidemic unseen, invisible or unreal?. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2004; 10(1): 1-3. 4. Angst J. The bipolar spectrum. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190(3): 189-91. 5. Manning JS, Connor PD, Sahai A. The bipolar spectrum : a review of the current concepts and implications for the management of depression in primary care. Arch Fam 5 Med 1998; 7(2): 63-71. 6. Bennazzi F. Bipolar II disorder and major depressive disorder : continuity or discontinuity. World J Biol Psychiatry 2006; 4(4): 166-71. 7. Mendlowicz M, Girardin JL, Kelsoe J, Akiskal HS. A comparison of recovered patients, healthy relatives of bipolar probands and normal controls using the short TEMPS-A. J Affect Disord 2005; 85(2): 147-50. 8. Akiskal HS, Djenderedjian AH, Rosenthal RH, Khani MK. Cyclothymic disorder : validating criteria for inclusion in the bipolar affective group. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 134(11): 1227-33. 9. Akiskal HS, Hantouche EG, Allilaire JF, Sechter D, Bourgeois ML, Azorin JM, Chatenet-Duchene L, Lancrenon S. Validating antidepressant associated hypomania (bipolar III) : a systematic comparison with spontaneous hypomania (bipolar II). J Affect Disord 2003; 73(1-2): 65-74. 10. Akiskal HS, Pinto O. The evolving bipolar spectrum : prototypes I, II, III and IV. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22(3): 517-34. 11. Angst J, Sellaro R, Stassen H, Gamma A. Diagnostic conversion from depression to bipolar disorders : results of a long term prospective study of hospital admissions. J Affect Disord 2005; 84(2-3): 149-57. 12. Akiskal HS, Mallaya G. Criteria for the soft bipolar spectrum : treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23(1): 68-73. 13. Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Towards a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity : epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord 2003; 73(1-2): 133-46. 14. Benazzi F. Prevalence of bipolar II disorder in atypical depression. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 1999; 249(2): 62-5. 15. Angst J, Gamma A, Sellaro R, Lavori PW, Zhang H. Recurrence of bipolar disorders and major depression : a lifelong perspective. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2005; 54(2): 139-47. 16. Judd LL, Shetler HJ, Akiskal HS, Maser J, Coryell W, Solomon D, Endicott J, Keller M. Long term symptomatic status of bipolar I versus bipolar II disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 6(2): 127-37. 17. Marneros A. Origin and development of the concept of bipolar mixed states. J Affect Disord 2001; 67(4-5): 229-40. 6