Teaching at an Internet Distance: the Pedagogy

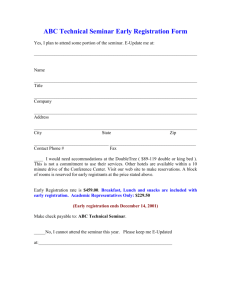

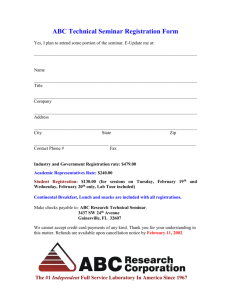

advertisement