MS Word - The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong

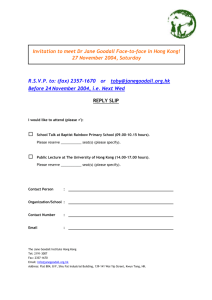

advertisement