Juhani Jussila

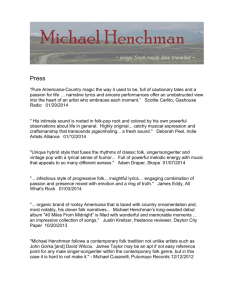

advertisement