The Atomic Bombs - Mercyhurst University

advertisement

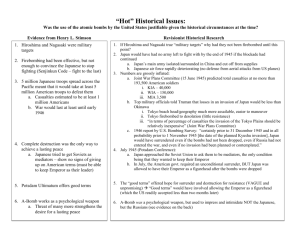

Brandt Schafer Applied Ethics Dr. Donahue 1 October 2013 Atomic Bomb Questions 1. The pro of letting the Japanese know before dropping the atomic bombs that they could keep a ceremonial emperor was that their civilians would protect their emperor at all costs, seeing it as their cultural duty. If they fought under the notion that their emperor would never be harmed, it defeated the purpose of dying in his name. The cons of letting them know were that they might use every resort to ensure that their emperor would reign victorious, even if everyone in Japan died except for him. Either way, the notion that appeared to fight Japan to the death would buy the United States enough time to finish the atomic bomb and avoid its own last resort (Mullins). 2. The pro of waiting for the Russians to enter the Pacific War before dropping the atomic bombs was obviously the strength in numbers and sheer military power: under no circumstances could Japan defeat the Soviet Union or the United States, let alone both of them. They would surrender instantly. The con of waiting for the Russians was the fear that they would settle in Japan just as they did and might have otherwise in other European and Asian nations. It would have had unacceptable post-war consequences because the United States would have even more opposing forces and fewer allies in the Cold War (Lewis). The decision to use the bomb before the Russians invaded essentially prevented their conflict from becoming “hot.” 3. It was arguably necessary to drop the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki because the Japanese may not have surrendered otherwise, and the Russians would have arrived merely a week later. It also provided scientists with data upon which radioactive element was more powerful: uranium or plutonium. The plutonium-based bomb, “Fat Man,” which Bock’s Car dropped on Nagasaki, had a larger field of detonation than the uranium-based bomb “Little Boy” that Enola Gay dropped on Hiroshima, but because of the geography and architecture of the city, resulted in fewer deaths and lesser property damage (“The Bombing of Nagasaki”). A cold joke could be that the scientists wanted to complete their hypothesis. 4. The mainland invasion, known as Operation Downfall, consisted of two phases. The first phase would begin on December 1st, 1945, and assault southern Kyushu. The second phase would assault Honshu on March 1st, 1946, exactly three months apart (MacArthur 395). The atomic bombs were dropped on August 6th, at 8:15 AM, above Hiroshima, and on August 9th, 1945, at 11:02 AM, above Nagasaki (“Introduction”). Delaying the dropping of the atomic bombs a few months would not have been a good idea, as the Soviet mainland invasion would take place even if they chose not to enter a week before they promised. Once again, the Japanese would surrender due to the massive opposing force, but the Cold War would become an even greater issue. The Japanese would be provided with the opportunity to kill thousands of American prisoners of war being held in Japan, because every second provided them with the opportunity to kill, torture and rape the prisoners, even innocent bystanders as seen in the Battle of Manila, also known as the Rape of Manila, in the same vein as the Rape of Nanking seven years beforehand (Kielley). 5. You would have to know before dropping such powerful weapons not only the present effects it will cause, such as thousands of deaths, millions of dollars of property damage, and severance of families, but also its future effects. Those who survived the bombs, colloquially known as “hibakusha,” received great discrimination from their peers. They were physically deformed, and as a result may have been fired from their jobs or harassed in public, in fear that their conditions were contagious. Hibakusha were also shunned in marriage, due to anxiety that their conditions were hereditary, or would die soon afterwards and not be able to provide for their spouse and children. The bombs impaired civilians who were not even part of the war for the rest of their lives simply because they resided on the islands of Japan (Gensuikin). 6. Enola Gay dropped “Little Boy” successfully hitting its original target of Hiroshima. However, Nagasaki was a secondary target: Bock’s Car was originally aiming to hit Kokura with “Fat Man,” but could not find the town in the incredibly cloudy weather. Major Sweeny then realized that there was only enough fuel to return to Okinawa, so he directed his plane to Nagasaki (“The Bombing of Nagasaki”). 7. The dropping of the atomic bombs was an indiscriminate attack. Chapter 3 Rule 12 of international humanitarian law states that the three qualities that define an indiscriminate attack are “(a)…not directed at a specific military objective; (b)…a…means of combat which cannot be directed at a specific military objective; …(c) …means of combat the effects of which cannot be limited” (International Committee of the Red Cross). Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not specific military objectives, and the atomic bomb was certainly not a weapon whose creators limited its power. Interestingly, people do not hesitate to admit that the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11th, 2001, were indiscriminate attacks, despite occurring in a larger city (New York is the size of Tokyo, Hiroshima is the size of New Orleans, and Nagasaki is the size of Aurora, Colorado). Nevertheless, all of these attacks occurred in non-military objective cities. 8. The dropping of the atomic bombs was not a last resort because it persuaded the Japanese to surrender prior to a mainland invasion, which would take not only thousands of Japanese lives, but also thousands of American lives (MacArthur 430). Such an invasion was the true last resort. America provided the Japanese many opportunities to surrender and project their remaining citizens. However, their own philosophy, “honorable death before surrender” lead to hundreds of thousands of instances of the former before the latter, until their best interest finally caved in (Gensuikin). 9. The dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki is statistically justified, as it prevented the deaths of thousands of both Americans and Japanese who would not be alive today otherwise. It was also politically justified, given the fact that it prevented the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union from becoming any worse with the possible inclusion of Japan as a rival. On the other hand, it was not morally justified to drop the atomic bombs, as a mere demonstration of its power may have persuaded the Japanese. However, both Secretary of War Henry Stimson and President Henry Truman denied this proposal, believing that this was unlikely: Japan already knew of the United States arsenal beforehand, so viewing the weapon from afar would not leave an impact (Glover 95-96). Furthermore, war by definition is unmoral, so to the military forces of America, it was a matter of ending what was already started: displaying the power of the bomb would prevent more deaths and destruction as seen in the Cold War. In the history of nuclear warfare, Japan is the only nation to receive any attack, let alone multiple. While the United States has tested over 1,100 bombs and Russia/U.S.S.R. over 900, Japan has tested absolutely zero (Rankin). This due to their three non-nuclear principles, established in 1974 by their government, stating that “we shall not manufacture nuclear weapons…possess them…and…not bring them into our country” (Sato). Perhaps these principles serve as evidence that any nation who falls victim to the atomic bomb will never want to associate with it ever again. Works Cited Glover, Jonathan. Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. Print. International Committee of the Red Cross. Customary International Humanitarian Law Database <http://www.icrc.org/customaryihl/eng/docs/v1_cha_chapter3_rule12>. 30 Sept. 2013. Kielley, Lindsay. “Japanese Actions: Treatment of Prisoners of War.” Bernardsville, New Jersey: Somerset Hills School District. 4 Aug. 1999. Web. 30 Sept. 2013. <http://library.thinkquest.org/26074/japanese.htm>. Lewis, Chris. “Debating the American Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb.” American Studies 2010 Course Website. Boulder, Colorado: University of Colorado. 21 Oct. 2002. Web. 29 Sept. 2013. <http://www.colorado.edu/AmStudies/lewis/2010/atomic.htm>. MacArthur, Douglas. “Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific.” Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Books Express Publishing. 20 June 2003. Web. 29 Sept. 2013. <http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur Reports/MacArthur V1/index.htm>. Mullins, Eustace C. “The Secret History of the Atomic Bomb: Why Hiroshima was Destroyed: The Untold Story.” June 1998. Web. 29 Sept. 2013. <http://www.whale.to/b/mullins8.html>. "Photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki." Gensuikin - Japan Congress Against Aand H-Bombs. 28 Oct. 2003. Web. 25 Sept. 2013. <http://www.gensuikin.org/english/photo.html>. Rankin, Bill. “Nuclear Explosions since 1945.” Radical Cartography. 2007. Web. 23 Sept. 2013. <http://www.radicalcartography.net/nuclear_full.png>. Sato, Eisaku. Nobel Lecture. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Foundation, 11 Dec. 1974. Web. 29 Sept. 2013. Taketa, Yasuhiko. “Testimony of Yasuhiko Taketa, a survivor of Hiroshima.” Gensuikin - Japan Congress Against A- and H-Bombs. Trans. Connie Prener. 28 Oct. 2003. Web. 25 Sept. 2013. <http://www.gensuikin.org/english/taketa.html>. The Avalon Project. “Introduction.” The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. New Haven, Connecticut: Lillian Goldman Law Library. 2008. Web. 29 Sept. 2013. <http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/mpintro.asp>. “The Bombing of Nagasaki.” History Learning Site. Web. 25 Sept. 2013. <http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/bombing_of_nagasaki.htm>.