CLINICAL SKILLS SERIES

Handouts for

Participants

Produced by

The Education Division

American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine

©2001 All Rights Reserved

Primary Care Approach to the Pelvic Examination

Important elements in a physical examination and focused sexual history

Preparation:

Introduce self to patient

Explain purpose of examination

Make sure patient has emptied her bladder

Check all materials and equipment, including non-sterile gloves, lubricant, speculum, mirror

and equipment for taking Pap and other diagnostic tests. Tip: A heating pad can be set up in

the examination table drawer to warm equipment.

Wash hands in the presence of the patient.

Check that table back is raised slightly and a pillow is available:

By elevating the table slightly the patient’s head and shoulders will be raised so that

she will be able to see the exam. This will also help to relax her abdominal muscles.

Cover the patient’s thighs and knees with drape.

Help patient to assume examination position:

Arrange the drape so that it falls between her legs.

Help patient place one heel at a time into foot rests.

Have her slide her buttocks down to edge of table until you direct her to stop.

Ask her to let her knees fall to the sides/Arrange drape for privacy.

Ascertain that the patient is comfortable.

Offer the patient a mirror so that she can familiarize herself with her own unique

anatomy. This will provide her a frame of reference for changes. Not all patients will

be interested.

Invite patient to ask questions at any time during the exam.

Before gloving adjust the light to illuminate the perineum. Wear gloves throughout the

examination and whenever handling equipment. (Be aware that readjusting light during the

exam can contaminate both the gloves and the light.)

Explain in advance each step of the examination and tell the patient what she might feel.

Avoid any unexpected or sudden movements. Always warn the patient when you will begin

and make initial contact on a neutral area such as the inner thigh before beginning palpation

or using speculum.

External Examination

Tell patient that you are going to perform an external examination and explain what you are

about to do; i.e. “now you’re going to feel me touch…”

Inspect and palpate the mons pubis, labia majora and perineum.

Separate the labia and inspect, looking for any ulceration, swelling, nodule, discharge or

lesions:

Labia minora

Clitoris

Urethral meatus

Vaginal opening or introitus

Inspect and palpate the Skene’s glands (these are small openings on either side of and

posterior to the urethral meatus)

Check the Bartholin’s gland by inserting index finger into vagina near the posterior end of

introitus. Palpate tissue between thumb and forefinger on one side. Note any tenderness,

swelling, discharge. Repeat same procedure on the other side.

Inspect the anus.

Ask patient to bear down to assess for cystocele/rectocele if indicated by history.

Speculum Examination

Choose proper size speculum and warm under running warm water (water serves as the

lubricant for both metal and plastic)

Alert patient that speculum examination is about to begin.

Insert speculum:

Hold speculum at 45-degree angle.

Open labia with opposite hand and introduce speculum into vagina directing it away

from the urethral meatus, pointing the tip of the speculum into the posterior fornix as if

aiming for the coccyx.

Insert blades gently and slowly into the vagina along the posterior wall (pointing

downward), depressing the perineal body and rotating at full insertion so that handle is

vertical.

Open speculum slowly, exposing cervix.

Tighten screw to hold in open position.

Observe cervical size, color, and outer os configuration, note any erosion, cyst, polyp, tumor,

eversion, etc.

Explain to patient any abnormalities found and have her use the mirror to observe if she

wishes.

Pap Smear/Other Screens

Obtain cervical specimen by inserting long narrow end of spatula into cervical os and rotate

360 degrees for Pap smear.

Obtain endocervical specimen by inserting cytobrush and rotating as indicated –please check

instructions as some models require 90 degree rotation, others 180 degree rotation etc.

Handle specimen according to correct procedure.

Hold blades open and release screw. Continue to hold blades open while withdrawing

speculum until blades are free of the cervix. Allow blades to close partially.

Inspect the vaginal walls as the speculum is withdrawn. Observe anterior and posterior walls,

noting vaginal rugae, bleeding, ulcers or tumors.

Note discharge: amount, character and color.

Allow speculum to close completely as it is withdrawn; be sure to angle speculum towards

posterior fornix as it is withdrawn, in order to prevent hurting the patient by grazing the

urethra.

Place speculum on paper towels or in tub provided (not in sink). Avoid spills on floor by

using paper towels when carrying speculum to sink area.

Bimanual Pelvic Examination

Apply lubricant to index and middle finger of gloved hand.

Alert patient that you are about to begin the bimanual exam.

Introduce distal segments of index and middle fingers into vagina (Use pubococcygeal

relaxation technique and press down on perineal body.)

Insert both fingers slightly into vagina and turn hand to palm up position; hyperextend

thumb and flex 4th and 5th fingers toward palm.

Palpate vaginal rugae, check for depth, deformity, scarring, cysts, etc.

Palpate cervix; note size, direction, configuration, consistency and tenderness.

Ask patient to take a deep breath and relax abdominal muscles. Patient should place

her arms at her side. Raising arms over the head may cause tightening of the abdominal

muscles.

Palpate uterine body between vaginal and abdominal hands, noting uterine size, position,

configuration, mobility, consistency, and sensitivity.

Move vaginal fingers into one lateral fornix. Place abdominal hand on the lower lateral

quadrant of the abdomen on the same side and attempt to palpate the ovary and parametrial

tissues, noting thickness of parametrial tissues and check for pelvic masses. Move vaginal

fingers into the other lateral fornix and abdominal hand to same side and repeat exam.

Bimanual Rectovaginal Examination

Remove fingers from vagina.

Reglove and apply lubricant to index and middle fingers.

Alert patient that the rectovaginal exam will begin.

Ask patient to bear down as finger is inserted into rectum (anal sphincter relaxation

technique).

Insert middle finger into rectum and index finger into vagina.

Repeat the palpation and characterization of the cervix, uterus, ovaries and parametrial

tissues from this posterior position.

Palpate posterior pelvic wall with a 180º sweep with the rectal finger.

Palpate rectovaginal septum between fingers using a scissor-like movement.

Remove fingers smoothly.

Offer patient tissues with which to wipe the area.

Help patient assume sitting position.

Again ask if she has questions.

Taking a Sexual History

Are you currently sexually active?

NO

Have you ever been sexually active?

NO

What caused you to stop?

With men, women or both?

Heterosexual activity

Homosexual / bisexual activity?

NO

Do you consider yourself to be gay /

lesbian / bisexual?

Is your current relationship monogamous?

How many previous sexual partners have you

had in your lifetime?

Do other people know of your sexual

preference or identity?

Have you or your partner(s) ever had STD or

used IV drugs?

Concerns, questions?

Have you ever been in situations where you felt abused?

Birth control?

Explore #, frequency, type:

anal, oral, vaginal?

NO

Have you always practiced safe sex (condoms)?

Do you have any questions or concerns about your sexual health?

Counsel

Tips for Taking a Sexual History

1. Use appropriate language

Use language that is clear and specific

Avoid euphemisms, jargon

Use non-judgmental terms

Listen and clarify any misunderstanding

Use patient’s language if appropriate

Check frequently for understanding

2. Assure confidentiality

3. Normalize the sexual history

Let the patient know what to expect.

Use a transition statement: “Now I’m going to ask you some questions about your sex

life and sexuality which may be difficult to talk about.”

Normalize the topic: “I ask all my patients these questions. It’s an important part of

your medical history that will help me to provide care for you.”

4. Start with an open-ended question:

“How are things going for you sexually?” or

“Are you sexually active? With men, women, or both?”

5. Use verbal and non-verbal facilitation skills

Elicit all concerns by asking, “Is there anything else?”

Silence may help the patient to talk about sensitive issues

Maintain appropriate eye contact, direct but not too prolonged

6. Normalize specific areas of inquiry

“Many women your age start to experience changes as they approach menopause. Are

you having any problems with vaginal dryness during intercourse?”

7. Respond to the patient’s emotions

Use empathy and restate the patient’s expressed feeling, “This seems very upsetting to

you.”

Legitimize the feeling, “It is understandable that you would feel this way.”

8. Complement the patient on things done well

“It is good that you are using condoms. It shows that you are protecting yourself.”

9. Remain non-judgmental

Maintain a neutral attitude and tone

The Three Most Common Vaginal Infections

Bacterial Vaginosis

Prevalence

BV is currently the most prevalent form of vaginal infection of reproductive age women in the

United States.2,3 The average incidence of BV has varied:

• 32%-64% in patients visiting sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics4-8

• 12%-25% in other clinic populations9,10

• 10%-26% in patients visiting obstetric clinics11-13

Background

Terminology: Bacterial vaginosis, the currently accepted name for this disease, has evolved

over almost 100 years. BV has been formerly known as: nonspecific vaginitis, Haemophilus

vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, Corynebacterium vaginalis.

Microbiology: BV is believed to represent a synergistic polymicrobial infection characterized

by an overgrowth of bacteria normally found in the vagina. Lactobacilli-dominated flora is

replaced with a mixed, predominantly anaerobic flora.

Anaerobes: Bacteroides spp, Peptostreptococcus spp, Mobiluncus spp

Facultative Anaerobes: Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis

Concentrations of anaerobic bacteria increase 100- to 1,000-fold in women with BV.10

Lactobacilli are absent or greatly reduced in BV patients.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with BV may present with a variety of symptoms or none at all. More than 50% of all

women with BV may be "without symptoms" (patients may have symptoms but do not

complain).14

1. Unpleasant, fishy or musty vaginal odor.

This malodorous vaginal discharge occurs in about 50%-75% of all patients.15,16 Odor is

caused by alkaline volatilization of various amine by-products of anaerobic

metabolism.17,18 Exacerbation of the odor may occur following sexual intercourse or

during menstruation as a result of a rise in vaginal pH.18

2. Increased vaginal discharge is common.19,20 Discharge is usually thin, gray or white,

and homogeneous; and it tends to adhere to the vaginal wall.21

3. Vaginal itching and irritation may be present.

Complications

BV has been associated with the following complications:

Gynecologic: Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), endometritis, cervicitis,4,22-24 postoperative

infections13,25, mildly abnormal Pap smear results (inflammation or atypical squamous cells

of undetermined significance [ASCUS]), and possible link with cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia (CIN).26

Obstetric: Preterm delivery, amniotic fluid infection,11,27 and preterm, premature rupture of

the membranes (PROM).27,28

Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis of BV is defined by three out of four of the following:

1. The presence of homogeneous discharge

2. pH >4.5

3. Positive KOH whiff test

4. Presence of clue cells on microscopic assessment of a saline smear10,28

Treating the Partner and the STD Debate

Numerous published clinical trials have failed to demonstrate a benefit in treating

sexual partners of women with BV. These trials have shown that the treatment of the

sex partners has not influenced the woman's response to therapy nor the relapse or

recurrence rate. According to the Centers for Disease Control's (CDC) STD treatment

guidelines, routine treatment of sex partners is not recommended.29

The argument that BV is an STD is widely debated. While BV is found more frequently in

sexually active women, BV has also been detected in virginal women.30 The common

recovery of G vaginalis from male sexual partners also obscures the issue of sexual

transmission.31 However, no relationship was found between BV recurrence and the

isolation of G vaginalis from sexual partners.32

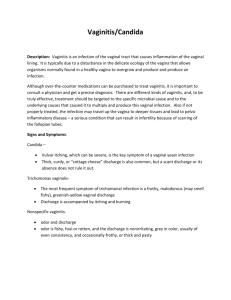

Candida Vaginitis (Yeast)

Prevalence

Candidiasis (yeast) is the second most common vaginal infection. True fungal infections

account for <33% of all vaginal infections.33

Background

Yeast infections are not associated with serious health risks.

Yeast infections are caused by one of many types of fungus called Candida (C albicans is

the most common pathogen; C glabrata and C tropicalis may also be present).

Candida and other organisms may be found in small numbers in the normal vagina as well

as in the mouth and digestive tract. Common causes of Candida overgrowth include:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Antibiotics

Diabetes

Pregnancy

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Signs and Symptoms

1. White, "cottage cheese-like" discharge

2. No odor

3. Vaginal and vulvar pruritis

Diagnosis

The diagnosis should be based on presence of hyphae or spores on KOH wet prep. Do not

base your diagnosis on a cheesy discharge and/or vulvovaginal itching, as these symptoms

may be present in other vaginal infections.

Perform culture only for refractory cases or relapses because up to 20% of women may

have positive cultures without disease.34 Evaluate patients with persistent infection for

diabetes and HIV.

Treating the Partner

Treatment of the patient's sexual partner does not improve the initial response to therapy nor

decrease the frequency of recurrence.

Trichomonas Vaginitis

Prevalence

Diagnosed in:

50%-75% of prostitutes

5%-15% of women visiting gynecology clinics

7%-32% of women in STD clinics

5% of women in family planning clinics 35

Background

Trichomonas vaginalis was initially identified by Donne in 1836 and is thought to be the first

recognized sexually transmitted pathogen.35

Trichomonas is caused by a single-cell parasite known as a trichomonad.

Since the parasite rarely causes symptoms in men, reinfection of women by untreated men

is common.

Risk factors for acquiring Trichomonas include: (1) multiple sexual partners (2) history of

previous STDs (3) coexistent infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or other STDs

Signs and Symptoms

1. Severe internal and external itching

2. Dysuria

3. Dyspareunia

4. Intense erythema of the vaginal mucosa

5. Yellow-green, frothy vaginal discharge

6. Foul, fishy odor

7. Cervical petechiae ("strawberry cervix")

Symptoms may worsen during menstruation.

Diagnosis

Look for motile trichomonads on saline smear (70% sensitivity).

Treating the Partner

Trichomonas is considered an STD; therefore, treatment of the sexual partner is necessary.

Reprinted with permission of the APGO - Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics

References

1.

Sobel JD. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:924-935.

2.

Sobel JD. Vaginitis in adult women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1990;17:851-879.

3.

Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Scaglione NJ. Bacterial vaginosis: current review with indications

for asymptomatic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1210-1216.

4.

Eschenbach DA, Hillier SL, Critchlow C, et al. Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of

bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:819-828.

5.

McCormack WM, Hayes CH, Rosner B, et al. Vaginal colonization with Corynebacterium

vaginale (Haemophilus vaginalis). J Infect Dis 1977;136:740-745.

6.

Embree J, Caliando J, McCormack W. Nonspecific vaginitis among women attending a

sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 1984;11:81-84.

7.

Hallen A, Pahlson C, Forsum U. Bacterial vaginosis in women attending STD clinics:

diagnostic criteria and prevalence of Mobiluncus spp. Genitourin Med 1987;63:386-389.

8.

Hill L. Anaerobes and Garnerella vaginalis in nonspecific vaginitis. Genitourin Med

1985;61:114-119.

9.

Speigel CA, Amsel R, Eschenbach DA, et al. Anaerobic bacteria in nonspecific vaginitis.N

Engl J Med. 1980;303:601-606.

10.

Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KCS, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Nonspecific

vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiological associations. Am J Med.

1983;74:14-22.

11.

Martius J, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, et al. Relationships of vaginal Lactobacillus species, cervical

Chlamydia trachomatis, and bacterial vaginosis to preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;

71:89-95.

12.

Gravett MG, Nelson HP, De Rouen T, et al. Independent associations of bacterial vaginosis

and Chlamydia trachomatis infection with adverse pregnancy outcome. JAMA.

1986;256:1899-1903.

13.

Gravett MG, Hummel D, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Preterm labor associated with

subclinical amniotic fluid infection and with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol.

1986;67:229-237.

14.

Hay PE, Taylor-Robinson D, Lamont RF. Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in a gynecology

clinic. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:63-66.

15.

Reamy KJ. Vaginitis. Journal of Clinical Practice in Sexuality. 1992:23-26.

16.

Dinsmoor MJ. Common vaginal discharges. Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality. May

1991:36-41.

17.

Chen KCS, Forsyth PS, Durfee MA, Pollack HM, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis: role of

Gardnerella vaginalis and treatment with metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1429-1434.

18.

Chen KCS, Amsel R, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Amine content of vaginal fluid from

untreated patients with nonspecific vaginitis. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:828-835.

19.

Pastorek JG. Bacterial vaginosis: current concepts of diagnosis and management. Infections

in Medicine. January 1992:48-52.

20.

Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Wilcoski LM, et al. Proline aminopeptidase activity as a rapid

diagnostic test to confirm bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:607-611.

21.

Holst E. Bacterial vaginosis: clinical and microbiological findings. In: Horowitz BJ, Mardh PA,

eds. Vaginitis and Vaginosis. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 1991:115-120.

22.

Roex AJM. Gynecological infections and strategies for treatment. Pharm Week 1 (Sci).

1990;12:268-274.

23.

Livengood CH. Bacterial vaginosis: treatment with topical intravaginal clindamycin

phosphate. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:118-123.

24.

Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis: emphasis on upper genital tract complications.

Sexually transmitted diseases. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:593-610.

25.

Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for

postcesarean endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:52-58.

26.

Eltabbakh GH, Eltabbakh GD, Broekhuizen FF, Griner BT. Value of wet mount and cervical

cultures at the time of cervical cytology in asymptomatic women. Obstet Gynecol.

1995;85:499-503.

27.

McGregor JA, French JI, Richter R, et al. Antenatal microbiologic and maternal risk factors

associated with prematurity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1465-1473.

28.

Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Anderson RJ. Statistical evaluation of diagnostic criteria for

bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:155-160.

29.

1993 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Morb Mortal Wky Rep. 1993;42

(RR- 14):68-70.

30.

Bump RC, Zuspan FP, Bueschling WJ III, et al. The prevalence, six-month persistence, and

predictive values of laboratory indicators of bacterial vaginosis (nonspecific vaginitis) in

asymptomatic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1984;150:917-924.

31.

Pheifer TA, Forsyth PS, Durfee MA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis: role of Haemophilus

vaginalis and treatment with metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1429-1434.

32.

Eschenbach DA, Critchlow CW, Watkins H, et al. A dose-duration study of metronidazole for

the treatment of nonspecific vaginosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1982;40(suppl):73-80.

33.

Willard M. Vulvovaginitis: a concise guide to office diagnosis and treatment. The Female

Patient. 1994; 19:11-16.

34.

Eschenbach DA, Hillier SL. Advances in diagnostic testing for vaginitis and cervicitis. J

Reprod Med. 1989;34 (suppl 18):555-564.

35.

Rein M, Muller M. Trichomonas vaginalis and trichomoniasis. In: Holmes KK, ed. Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. 2nd ed. New York, NYMcGraw-Hill Publishing Co; 1990:581-592.

36.

Hillier SL, Holmes K. Bacterial Vaginosis. In: Holmes KK, ed. Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing Co; 1990:547-559.

37.

Sobel JD, Cook RL. Lactobacilli: a role in controlling the vaginal microflora? In: Horowitz BJ,

Mardh PA, eds. Vaginitis and Vaginosis. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 1991:46-53.

Differential Diagnosis of Vaginal Infections

Syndrome

Diagnostic

Criteria

Normal

Bacterial Vaginosis

Trichomonas Vaginitis

Candida Vulvovaginitis

Vaginal pH

3.8-4.2

>4.5

>4.5

< or = 4.5 (usually)

Discharge

White, clear, flocculent

Thin, homogeneous, white, gray,

adherent, often increased

Yellow-green, frothy, adherent,

increased

White, curdy, “cottage cheeselike”, sometimes increased

Absent

Present (fishy)

May be present (fishy)

Absent

None

Discharge, bad odor (possibly

worse after intercourse), possible

itching

Frothy Discharge, Bad odor,

vulvar pruritus, dysuria

Itching/burning, discharge

Amine odor (KOH

whiff test)

Main Patient

Complaints

Microscopic

Lactobacilli (1), epithelial cells

(2)

Clue cells (3) with adherent

coccoid bacteria, no WBCs

Trichomonads (4), White Blood

Cells>10/hpf (5)

Budding yeast (6), hyphae,

pseudohyphae (7) w/KOH prep

Four Quick Tests For Vaginal Infections

1. Pelvic examination

Allows for the visual inspection of the whole genital area and for collection of vaginal

secretions for analysis.

2. pH test

Allows for a quick indication of which infection a patient might have. Recent intercourse

or douching may interfere with results.

a. pH 3.8-4.2 = Normal

b. pH>4.5 = BV or Trichomonas

c. pH<4.5 = Candida

Instructions: Take a small amount of vaginal fluid from the lateral and proximal third

of the vaginal wall and smear it on pH paper.

Saline falsely elevates pH.

Lubricant can falsely change pH.

Endocervical secretions have higher pH than vaginal secretions

Cervical and menstrual secretions tend to be alkaline.

3. Wet mount

Microscopic examination of a slide prepared from vaginal secretions.

Preparation of slide:

1. Draw line middle of glass slide with grease pencil

2. Add 2 drops of saline to left of line

3. Add 2 drops of 10%-20% KOH to right of line.

4. Apply sample of vaginal fluid to saline, making 2-3 rotations in saline to ensure a

dilute sample.

5. Apply second sample of vaginal fluid to KOH side of slide, making 10-15

rotations of swab in KOH to assure a fairly concentrated sample.

6. Place cover slip over samples and view under a microscope, scanning both sides of

the slide. Try 4-10X or >40X objective settings.

7. In KOH sample look for mycelia or pseudomycelia (Candida)

8. In saline sample look for:

Presence of WBCs (consider upper genital tract infection or Trichomonas)

Motile pear-shaped organisms (Trichomonas)

Presence of Clue cells, squamous epithelial cells whose borders are obscured

by an overgrowth of bacteria (BV)

Mycelia (Candida)

4. KOH Whiff test

Mix 10%-20% KOH with vaginal fluid to detect a foul, fishy odor. This strong odor is

indicative of BV or Trichomonas.

Perform this test immediately after mixing the vaginal sample into the KOH. Pass swab

under nose for a quick whiff before discarding.

KOH is alkaline and will volatilize the amines produced by BV or Trichomonas if they are

present.