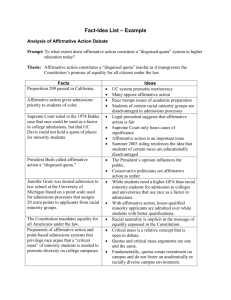

update on affirmative action/diversity litigation

advertisement

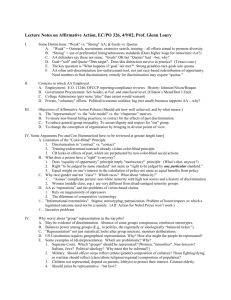

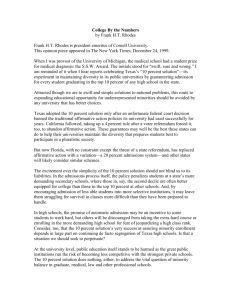

UPDATE ON AFFIRMATIVE ACTION/DIVERSITY LITIGATION June 26-29, 2002 Alexander E. Dreier Hogan & Hartson L.L.P. Washington, D.C. Introduction This outline summarizes selected legal authorities pertinent to affirmative action in higher education. It is not comprehensive. It includes constitutional, statutory and regulatory provisions; Supreme Court decisions; state initiatives; and lower federal and state court decisions. The final section summarizes the state of the law in each federal judicial circuit concerning the diversity justification for affirmative action in education or other contexts. I. Constitutional, Statutory, and Regulatory Provisions U.S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment. “No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” 42 U.S.C. § 1981. “All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.” See, e.g., Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) (Section 1981 extends to purely private acts of discrimination); McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976) (Section 1981 protects white as well as non-white employees). Title VI, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d. “No person . . . shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (“OCR”) regulations under Title VI (“Nondiscrimination under programs receiving federal assistance through the Department of Education effectuation of Title VI,” 34 C.F.R. Part 100). “In administering a program regarding which the recipient has previously discriminated against persons on the ground of race, color, or national origin, the recipient must take affirmative action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination. . . . Even in the absence of such prior discrimination, a recipient in administering a program may take affirmative action to overcome the effects of conditions which resulted in limiting participation by persons of a particular race, color, or national origin.” 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) and (ii). “For example, where a university is not adequately serving members of a particular racial or nationality group, it may establish special recruitment policies to make its program better known and more readily available to such group, and take other steps to provide that group with more adequate service.” 34 C.F.R. § 100.5(i). National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 OCR Policy Interpretation under Title VI (44 Fed. Reg. 58509, October 10, 1979). Encourages higher education institutions “to continue and expand voluntary affirmative action programs to increase their enrollment of minority group members and to attain a diverse student body.” Institutions may consider “race, color, or national origin as a positive factor, with other factors, such as geographic or economic circumstance, in selecting from among qualified candidates,” and may “modify admissions criteria for minorities. . . necessary for a fair appraisal of the academic promise of minority applicants,” offer special services, and establish “numerical goals.” OCR policy on minority-targeted student aid (“Department of Education Final Policy Guidance on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its implementing regulations,” 59 Fed. Reg. 8756, February 23, 1994). A college or university may award financial aid taking into account, among other factors, recipients’ race or national origin if aid is needed to overcome effects of past discrimination. Finding of discrimination may be by court or administrative agency, or aid awarded without such finding if institution is prepared to demonstrate strong basis in evidence for concluding that action was necessary to remedy effects of its past discrimination. To promote diversity, institutions may also consider race or national origin among other factors in awarding aid, or use race or national origin as condition of aid eligibility “if this use is narrowly tailored, or, in other words, if it is necessary to further its interest in diversity and does not unduly restrict access to financial aid for students who do not meet the race-based eligibility criteria.” See also Letter from Judith A. Winston, General Counsel, United States Department of Education, to College and University Counsel (July 30, 1996) (“it is permissible in appropriate circumstances for colleges and universities to consider race in making admissions decisions and granting financial aid”). Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2). Employers shall not “fail or refuse to hire or discharge any individual, or otherwise discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” II. State Initiatives California Proposition 209. “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.” “Nothing in this section shall be interpreted as prohibiting action which must be taken to establish or maintain eligibility for any federal program, where ineligibility would result in a loss of federal funds to the state.” Cal. Const. art. I, § 31. One Florida Initiative. “Neither State University System nor individual university admissions criteria shall include preferences in the admissions process for applicants on the basis of race, national origin or sex.” Fla. Admin. Code Ann. R. 6C-6.002(7). National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 Washington State Initiative 200. “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.” “This section does not prohibit action that must be taken to establish or maintain eligibility for any federal program, if ineligibility would result in a loss of federal funds to the state.” Wash. Rev. Code Ann. ch. 49.60, notes. III. United States Supreme Court Decisions Regents of University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). In challenge to public medical school affirmative action admissions plan under Title VI and Fourteenth Amendment, Court held constitutional the objective of fostering student body diversity, where race a “plus” factor, not more. Justice Powell’s tie-breaking opinion cited academic freedom, but rejected as justifications reducing deficit of minorities in medical schools and profession, remedying societal discrimination, and increasing number of physicians who practice in underserved areas. Court held unlawful setting aside places for minority students. United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979). Private, voluntary preferences permissible under Title VII where job category “traditionally segregated,” interests of nonminorities not unnecessarily trammeled, and program temporary, “not intended to maintain a racial balance, but simply to eliminate a manifest racial imbalance.” Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980). Congressionally-mandated minority set-aside program upheld against Fourteenth and Fifth Amendment challenge. Racial or ethnic criteria when narrowly tailored may be used to cure effects of past discrimination. Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983). University must have racially nondiscriminatory policy as to students to be tax-exempt. Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commission of the City of New York, 463 U.S. 582 (1983). Title VI prohibits intentional classifications based on race for purpose of affirmative action, to same extent as Fourteenth Amendment. Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S. 267 (1986). In constitutional challenge to public employer’s voluntary affirmative action plan that entailed race-conscious layoff of teachers, Court held preferences lawful under Fourteenth Amendment if “narrowly tailored” to meet “compelling state purpose”; disapproved objective of providing faculty role models for students to remedy societal discrimination; upheld objective of overcoming current effects of identified past discrimination. Institution need not be subject to finding of past discrimination or admit past discrimination to adopt voluntary affirmative action plan. United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987). Upheld against constitutional challenge court order requiring public employer to implement affirmative action plan with numerical racial quotas. Factors justifying plan: It was necessary to eliminate pervasive, open, long-term National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 discrimination; effective, alternative remedies not found; plan temporary and flexible; quotas did not trammel rights of non-minorities. Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara County, 480 U.S. 616 (1987). Public employer’s affirmative action plan upheld under Title VII where there was “manifest imbalance” of women in skilled craft jobs; plan flexible; used goals, not “rigid numerical quotas”; rights of nonminorities not trammeled; plan temporary, intended to attain, not maintain, balanced workforce. City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989). In constitutional challenge to minority business set-aside established by public entity, Court required “strict scrutiny” of voluntary race-sensitive state or local government affirmative action plans. State and local governments must show that preferential program is narrowly tailored to meet compelling need. Proponent must show “‘strong basis in evidence for its conclusion that remedial action [is] necessary’“; race-neutral alternatives must be explored; and plan may not unduly infringe third parties’ rights. Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 497 U.S. 547 (1990). Federal Communications Commission minority broadcast licensing preferences narrowly upheld under Fifth Amendment because they “promoted important government objective of broadcast diversity.” Preferences “imposed only slight burdens on non-minorities who had no firmly rooted expectation” of obtaining broadcast license; and, of “overriding significance” in Court’s view, Congress mandated preferences. United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S. 717 (1992). Adoption of race-neutral policies alone does not fulfill obligation to disestablish prior de jure segregated Mississippi university system. Title VI prohibits race or national origin discrimination to same extent as Equal Protection Clause. Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, 515 U.S. 200 (1995). Constitutional challenge by nonminority business to federal highway construction program race-preference provisions. Prime contractors received incentive payments if at least ten percent of work subcontracted to disadvantaged businesses, presumptively including firms owned by African-Americans, Hispanics or other minorities. Federal preference assessed under Croson “strict scrutiny” standard. Overruled more lenient Metro Broadcasting standard (that federal government can more freely engage in affirmative action than state or local government). Court did not discuss diversity. On remand, district court held challenged statutes and regulations, although serving compelling interest in remedying past discrimination, unconstitutional because not narrowly tailored. National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 Texas v. Lesage, 120 S. Ct. 467 (1999) (per curiam). Dismissed Section 1983 claim of Caucasian African immigrant denied admission to University of Texas Ph. D. program. Plaintiff, who would have been rejected based on his qualifications under a race-neutral policy, suffered “no cognizable injury.” Dicta states that forward-looking injunctive relief would have been available. IV. Federal Circuit and District Court Decisions Flanagan v. Georgetown College, 417 F. Supp. 377 (D.D.C. 1976). In pre-Bakke decision, scholarships for minority or disadvantaged students in support of affirmative action program designed to increase minority enrollment held to violate Title VI. Allocating “60% of . . . available scholarship funds to 11% of [the] entering [class] . . . is arbitrary [and] offends against the non-discrimination provisions of [Title VI] . . . .” Davis v. Halpern, 768 F. Supp. 968 (E.D.N.Y. 1991). University unsuccessfully sought summary judgment in challenge to affirmative action policy by white male denied admission. Absent prior discrimination by City University of New York, consideration of race as one admissions factor held constitutional only to extent it sought to advance educational benefit of diverse student body. University held not to have clearly articulated permissible diversity justification. Washington Legal Foundation v. Alexander, 984 F.2d 483 (D.C. Cir. 1993). Rejected on standing grounds challenge by foundation and seven students enrolled at universities that had minority-targeted financial aid programs, who sought to compel Secretary of Education to enforce Title VI. Knight v. Alabama, 14 F.3d 1534 (11th Cir. 1994). Upheld race-conscious remedies including scholarships to increase student racial diversity at certain college campuses, in case involving state higher education system in which effects of past race discrimination persist. Podberesky v. Kirwan, 38 F.3d 147 (4th Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 115 S. Ct. 2001 (1995). In challenge to race-exclusive minority scholarship program initiated as part of compliance plan following OCR finding that university not in compliance with Title VI, and continued as part of effort to overcome present effects of past discrimination, court held university failed to prove it suffered such effects and that scholarship program was narrowly tailored to overcome underrepresentation and low graduation and retention rates. Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 116 S. Ct. 2581 (1996). University of Texas Law School admissions process that targeted percentages of Mexican-American and African-American students unconstitutional. District court reliance on Justice Powell opinion in Bakke for proposition that diversity is compelling interest held misplaced; because opinion did not represent Supreme Court majority and because recent affirmative action decisions indicate contrary position, Justice Powell’s endorsement of diversity as compelling interest for raceconscious admissions not binding. University offered these interests to justify policy: Providing state’s largest minority groups opportunities for admission; fulfilling OCR compliance plan that National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 required increased effort to recruit Mexican- and African-Americans; complying with professional associations’ student diversity standards. In later appeal after remand, a different panel upheld district court’s award of only token damages because plaintiffs were not qualified under a constitutional admissions system, but declined to overturn the Hopwood I holding that diversity is not a compelling interest. 236 F.3d 256 (5th Cir. 2000), cert. denied, 533 U.S. 929 (2001). Stanley v. Darlington County School District, 1996 WL 294369 (D.S.C. May 24, 1996). Upheld plan to ensure high school “student body will be a well qualified, racially balanced group of young people,” but noted that “relief ordered here is designed to remedy the effects of racial discrimination, not merely to further an interest in diversity.” Taxman v. Board of Education of Township of Piscataway, 91 F.3d 1547 (3d Cir. 1996), cert. granted, 117 S. Ct. 2506, cert. dismissed, 118 S. Ct. 595 (1997). Promotion of public high school faculty racial diversity insufficient to justify race-conscious layoff of teacher. Title VII bars affirmative action to achieve diversity. Remedying past discrimination is only permissible purpose of race-conscious programs under Title VII. (After Supreme Court granted certiorari, civil rights groups contributed to settlement.) Ayers v. Fordice, 111 F.3d 1183 (5th Cir. 1997). African-Americans challenged Mississippi’s allegedly racially dual public higher education system. State need not remedy all present discriminatory effects of de jure system, but only discriminatory “consequences [that] flow from policies rooted in the prior system.” Doe v. Department of Health and Human Services (S.D. Tex., complaint filed Feb. 14, 1997). White high school student denied admission to Texas A&M summer science program that admitted only minority students sued university, federal agencies, State of Texas, and private sponsor. In 1997, NIH and USDA agreed to abandon race and ethnicity criteria and pay plaintiff’s legal fees. National Science Foundation (NSF) and State of Texas settled a separate lawsuit with same plaintiff in connection with similar summer camp. Woods v. Wright Institute, 1998 WL 133035 (9th Cir. Mar. 24, 1998). Rejected AfricanAmerican woman’s claim that she was denied admission to graduate program because of race. “[N]onexclusive use of subjective criteria in the educational setting . . . is clearly a permissible means of determining admissibility of students.” [Unpublished opinion.] Kidd v. National Science Foundation (E.D. Va., complaint filed December 12, 1997). White Clemson University graduate student who failed to win one of 2250 graduate research fellowships sued NSF, claiming he was denied opportunity to apply for one of 400 additional slots reserved for minority students. After district court denied plaintiff’s preliminary injunction motion and denied NSF’s motion to dismiss for lack of standing, case settled. Wessmann v. Gittens, 160 F.3d 790 (1st Cir. 1998). Boston Latin School could not set aside seats in proportion to racial composition of qualified applicants, whose grades and test scores National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 were above fiftieth percentile. Court assumed “Bakke remains good law” and criticized Hopwood panel. Policy not narrowly tailored to achieve diversity because: no necessary link between policy and purported goals; exclusive focus on racial and ethnic diversity, and on only five minority groups; policy unnecessary to achieve sufficient diversity or prevent “racial isolation.” No strong basis in evidence that policy needed to remedy past discrimination. Pollard v. State of Oklahoma, (W.D. Okla., complaint filed October 20, 1998). White male challenged, under Equal Protection Clause and civil rights statutes, state scholarship program that used different ACT and SAT cut-off scores for males and females and racial and ethnic groups. Case settled, and program qualification criteria were amended. Tuttle v. Arlington County School Board, 195 F.3d 698 (4th Cir. 1999), cert. dismissed, 529 U.S. 1050 (2000). School board policy that “weighted” applications to alternative school according to race/ethnicity and other factors was not narrowly tailored to promote educational benefits of diversity. Although whether diversity may be compelling interest remains unresolved in Circuit, “[n]on-remedial racial balancing is unconstitutional.” Eisenberg v. Montgomery County Public Schools, 197 F.3d 123 (4th Cir. 1999), cert. denied, 529 U.S. 1019 (2000). School district policy that permitted denial of student transfers that would contribute to racial isolation was unconstitutional. Left open question whether diversity can be compelling interest, but held policy to be unlawful “non[-]remedial racial balancing.” Hunter by Brandt v. Regents of the University of California, 190 F.3d 1061 (9th Cir. 1999), cert. denied, 531 U.S. 877 (2000). University’s elementary school that researched University’s educational techniques could consider race, to make study scientifically credible. California’s “compelling interest in providing effective education to its diverse, multi-ethnic, public school population” was furthered by studying diverse student population. Boston’s Children First v. City of Boston, 62 F. Supp. 2d 247 (D. Mass. 1999). Order denying request for “broad” preliminary injunction prohibiting race as factor in student assignment. Stated Wessmann did not hold that diversity can never be a compelling interest. Circumstances distinguished from Wessmann in that here claims were broader; diversity may be more important in elementary school; and plan may be more narrowly tailored. Comfort v. Lynn School Committee, 100 F. Supp. 2d 57 (D. Mass. 2000). Order denying preliminary injunction. Validity of race-conscious student assignment plan to achieve diversity would be decided on factual record. Brewer v. West Irondequoit Central School District, 212 F.3d 738 (2d Cir. 2000). In challenge by white student to program that permitted minority students to transfer to suburban schools and white students to transfer to city schools, court held that earlier circuit precedent “explicitly establish[es] that reducing de facto segregation . . . serves a compelling government interest” and National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 that “the state has a compelling interest in ensuring that schools are relatively integrated.” Vacated preliminary injunction and remanded for trial. Gratz v. Bollinger, 122 F. Supp. 2d 811 (E.D. Mich. 2000). Upheld University of Michigan undergraduate admissions procedure. Court held that “under Bakke, diversity constitutes a compelling governmental interest,” and cited the University’s expert evidence on the educational benefits of student diversity. The University’s “point-based” undergraduate admissions policy was narrowly tailored, because it entailed no rigid quotas and took race into account in two ways the court held lawful: (1) bonus points could be added for minority status, as well as geographic factors, alumni relationship, and other considerations, and (2) applications of minorities, and others with qualities or characteristics deemed important, who met academic standards could be “flagged” for further consideration. Pre-1999 policies that, the court found, protected seats for minorities and used different “grids” for minority and white applicants, were unlawful. Appeal is pending. Smith v. University of Washington Law School, 233 F.3d 1188 (9th Cir. 2000), cert. denied, 532 U.S. 1051 (2001). Affirmed denial of partial summary judgment for plaintiffs, unsuccessful applicants to University of Washington Law School who claimed that diversity may never justify consideration of race. Embraced Justice Powell’s opinion in Bakke; disagreed with what it termed the Fifth Circuit’s “flaw[ed]” analysis of the Bakke decision in Hopwood; and concluded that “educational diversity is a compelling governmental interest that meets the demands of strict scrutiny.” Plaintiffs’ request for broad injunction was moot because, after enactment of Washington State Initiative 200, the Law School amended its policy to omit race as an admissions factor. Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 269 F.3d 305 (4th Cir. 2001) (en banc), cert. denied, 122 S. Ct. 1537 (2002). School district had achieved unitary status, but its raceconscious magnet school lottery was lawful because district was under desegregation order when policy was applied. District acted in good faith to comply with desegregation orders, and “it is necessary to afford a school board some latitude in attempting to meet its desegregative obligations.” District court abused discretion in enjoining consideration of race in student assignments. Whether diversity is compelling interest remains open question in Fourth Circuit, but court said, in dicta, that magnet policy, which included strict racial balance guidelines, would be unconstitutional if adopted by a unitary school district. Johnson v. Board of Regents of the University of Georgia, 263 F.3d 1234 (11th Cir. 2001). Court declined to decide whether promotion of student body diversity is a compelling interest – finding Justice Powell’s opinion in Bakke not binding precedent – because University of Georgia’s diversity-based freshman admissions was not narrowly tailored to meet that interest. At one stage of admissions process, University assigned points to various demographic factors, including race and ethnicity. Weight accorded to race as a factor in admissions must not be “subject to rigid or mechanical application” and must “remain flexible enough to ensure that each applicant is evaluated as an individual”; “membership in a favored or disfavored group” must not be the “defining feature of her candidacy.” Race-neutral factors that contribute to diversity must National Association of College and University Attorneys 8 be taken into account; race must be used in a way that “does not give arbitrary or disproportionate benefit to members of the favored racial groups”; and institution must show race-neutral alternatives were considered and are inadequate. Weser v. Glen, 190 F. Supp. 2d 384 (E.D.N.Y. 2002). Against race and sex discrimination claims by rejected white male applicant, granted summary judgment for public law school that achieves diversity by “actively recruiting a diverse applicant pool and not by preferences in the admissions process.” “[C]onsciousness of race and gender in the formulation of an admissions policy is not tantamount to discrimination.” Grutter v. Bollinger, __ F.3d __, 2002 WL 976468 (6th Cir. May 14, 2002). Upheld raceconsciousness in the University of Michigan law school admissions policy. Justice Powell’s Bakke opinion is “binding” because it was the “narrowest grounds” for decision in that case. Noting that colleges and universities “have been relying on Bakke for more than twenty years,” the majority concluded that “Bakke remains the law until the Supreme Court instructs otherwise.” The majority found the Michigan law school policy to be narrowly tailored to achieve diversity. It “closely tracks the Harvard plan” endorsed in Bakke by considering race and ethnicity as one of several possible “plus” factors that do not insulate minority applicants from competition with non-minorities. Unlike the University of California at Davis procedure that Bakke struck down, the Michigan policy does not include a quota or a separate committee or review process for minority applicants. Based on “overwhelming” testimony and a “presumption that academic institutions act in good faith,” the court distinguished the law school’s pursuit of a critical mass of minority students from a quota. Because it upheld the policy, the court did not reach the question, raised by student intervenors, whether it was a permissible remedy for past discrimination. Judge Clay’s concurrence said the university’s extensive expert evidence on diversity’s educational benefits confirmed that its pursuit is indeed “compelling”. Judge Boggs’ dissent argued that the Powell opinion is insufficient support for the diversity rationale, and racial and ethnic diversity, as distinct from “experiential diversity,” is not a compelling interest. The Michigan policy is not narrowly tailored, the dissent said, because it gives minority applicants a significant advantage; seeking a “critical mass” of minorities amounts to a quota and was not shown to advance education; and the law school overlooked race-neutral alternatives. V. State Court Decision University and Community College System of Nevada v. Farmer, 930 P.2d 730 (Nev. 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 1186 (1998). Upheld state university unwritten policy that allowed academic departments to hire additional faculty member following placement of minority candidate. Court identified faculty diversity as compelling interest, holding program satisfied Bakke because race was one among many factors, and goal of achieving racially diverse faculty was analogous to goal of diverse student body. Plan also held to satisfy Title VII because it furthers Title VII purposes without trammeling white employees’ rights, and aims to attain, not maintain, racial balance among faculty only one percent African-American. National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 VI. The Diversity Justification For Affirmative Action: Selected Authorities By Federal Circuit Summarized below is the state of the law in each federal judicial circuit concerning the diversity justification for affirmative action in education, or in other contexts. First Circuit. Assumed without deciding that “Bakke remains good law” and endorsed, as abstract matter, the educational benefits of diversity. See Wessmann v. Gittens, supra. But court scrutinized public high school set-aside policy’s “concrete workings,” and rejected policy because no necessary link between policy and educational goals; exclusive focus on racial and ethnic diversity and on five minority groups; policy unnecessary to achieve sufficient diversity or prevent “racial isolation.” Id. Massachusetts district court noted diversity may be more important in elementary school than at higher levels. Boston Children’s First, supra. See also Comfort, supra. Same district court rejected police department diversity defense of affirmative action program. Cotter v. City of Boston, 193 F. Supp. 2d 323 (D. Mass. 2002). Second Circuit. Held that “reducing de facto segregation” in public schools “serves a compelling government interest” and that “the state has a compelling interest in ensuring that schools are relatively integrated.” Brewer v. West Irondequoit Central School District, supra. Precedent also accords universities “wide latitude . . . to define and carry out their own educational missions” and a program’s “value to students” also “involves the people they encounter in the process.” Carroll v. Blinken, 957 F.2d 991, 999-1000 (2d Cir. 1992) (upholding mandatory student activities fee because it stimulated extracurricular activity and campus debate). In pre-Adarand decision, district court held “consideration of race as one factor among many by a university admissions process is constitutional only so far as it seeks to procure for the university the educational benefits which flow from having a diverse student body.” Davis v. Halpern, supra. Same court subsequently rejected diversity rationale in context of police department affirmative action, see Hiller v. County of Suffolk, 977 F. Supp. 202 (E.D.N.Y. 1997), but another district court held that “need for effective law enforcement” can be compelling interest that could justify race-conscious transfer of minority police officers to ease racial tensions, Patrolmen’s Benevolent Ass’n v. City of New York, 74 F. Supp. 2d 321, 329 (S.D.N.Y. 1999). Third Circuit. Rejected diversity, and all non-remedial rationales, as justification for raceconscious decisions in Title VII context. See Taxman v. Board of Educ. of the Township of Piscataway, supra (rejecting school board decision to lay off white teacher, rather than AfricanAmerican, to preserve faculty diversity). However, court suggested diversity justification might be permissible in higher education admissions. Fourth Circuit. In two cases involving public schools, explicitly left open question whether diversity can be compelling interest in education, but invalidated race-conscious policies as not narrowly tailored. Tuttle v. Arlington County Sch. Bd., supra; Eisenberg v. Montgomery County Public Schs., supra. See also Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., supra. Evaluated constitutionality of diversity justification in fire department hiring. See Alexander v. Estepp, 95 National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 F.3d 312 (4th Cir. 1996). While not expressly ruling on validity of diversity justification, challenged policy held not narrowly tailored because means less drastic than race classification were available. Circuit’s rhetoric suggests hostility to diversity justification, see, e.g., Podberesky v. Kirwan, supra, and that Circuit may view remedial justification as exclusive for race-conscious decisions. See also Stanley v. Darlington County Sch. Dist., 1996 WL 294369, at *3 (D.S.C. May 24, 1996). Fifth Circuit. State interest in using race to achieve diverse student body not compelling under strict scrutiny. Hopwood v. Texas, supra. Since Hopwood, court continues to reject diversity as justification for affirmative action. See, e.g., Messer v. Meno, supra (“Diversity programs, no matter how well-meaning, are not constitutionally permissible absent a specific showing of prior discrimination . . . .”). Sixth Circuit. Held that pursuit of student body diversity is a compelling interest, and upheld University of Michigan law school admissions policy as narrowly tailored. Grutter v. Bollinger, supra. District court upheld University of Michigan undergraduate admissions. Gratz v. Bollinger, supra. Appeal was pending when this outline went to press. Seventh Circuit. Suggested that correction of “racial imbalance” could not justify school racebased layoff policy. Britton v. South Bend Community Sch. Corp., 819 F.2d 766, 770-71 (7th Cir. 1987). Also, in non-education context, declared “a majority of the Justices of the Supreme Court believe that racial discrimination in any form, including reverse discrimination, is unconstitutional when done by states or municipalities, unless the purpose is to provide a remedy for discrimination against the favored group.” Milwaukee County Pavers Ass’n v. Fiedler, 922 F.2d 419, 421-22 (7th Cir. 1991). Yet Judge Posner upheld nonremedial use of race in prison boot camp. Wittmer v. Peters, 87 F.3d 916 (7th Cir. 1996); see McNamara v. City of Chicago, 138 F.3d 1219, 1222 (7th Cir. 1998) (nonremedial affirmative action can be permissible in “policing and corrections”). In Back v. Bayh, 933 F. Supp. 738 (N.D. Ind. 1996), court rejected diversity rationale for race and gender quotas in county judicial nominating commission: “Without prior discrimination, the government does not have a compelling interest for imposing a racial classification.” “[D]esire for diversity or to have more minorities is not an interest sufficient to justify governmental race-based actions.” Eighth Circuit. Has not directly addressed diversity justification for affirmative action in education. In Valentine v. Smith, 654 F.2d 503 (8th Cir. 1981), declared, “[a]bsent findings of past discrimination, courts cannot ascertain that the purpose of the affirmative action program is legitimate” and stated in dicta that “validity of a state’s affirmative action program should depend on a determination of the relation of the preference to the purpose of remedying past discrimination.” But one district court, in unpublished opinion upholding remedial justification for affirmative action plan, stated police department diversity is also “a compelling end in its own right.” Police Officers’ Federation v. City of Minneapolis, 2001 WL 856021, at *7 (D. Minn. July 27, 2001). National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 Ninth Circuit. In Smith v. University of Washington Law School, supra, rejected plaintiffs’ argument that diversity may never justify consideration of race. In upholding law school’s reliance on diversity rationale, court embraced Justice Powell’s opinion in Bakke; disagreed with the “flaw[ed]” analysis of Bakke in Hopwood; and concluded that “educational diversity is a compelling governmental interest that meets the demands of strict scrutiny.” See also Hunter by Brandt, supra. Tenth Circuit. Has declared in employment context that “purpose of race-conscious affirmative action must be to remedy the effects of past discrimination against a disadvantaged group that itself has been the victim of discrimination.” Cunico v. Pueblo Sch. Dist. No. 60, 917 F.2d 431, 437 (10th Cir. 1990). In rejecting policy to “protect with special consideration the only black administrator in the district,” reasoned that “only goal that is discernible in the . . . decision to retain the [African-American social worker] is that of ‘outright racial balancing,’“ and action therefore not narrowly tailored. Eleventh Circuit. In Johnson v. Board of Regents of the University of Georgia, supra, declined to decide whether diversity is a compelling governmental interest, and held Justice Powell’s opinion in Bakke not binding precedent, “although a majority of the Supreme Court may eventually adopt [it].” The court thought it “possible that the important purpose of public education and expansive freedoms of speech and thought associated with [the] university environment” might “on a powerful record justify treating student body diversity as a compelling interest,” but concluded that “[t]he weight of recent precedent is undeniably to the contrary.” In non-education contexts, district courts have rejected diversity rationale. One, addressing police department program, stated, “desire for diversity is not compelling enough to meet strict scrutiny.” Kane v. Freeman, 1997 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4063, at *18 (M.D. Fla. Mar. 17, 1997). Another rejected raceconscious selection of judicial nominating commission members, declaring interest in diversity alone insufficient. Mallory v. Harkness, 895 F. Supp. 1556, 1560 (M.D. Fla. 1995). Same court noted it rejected diversity rationale as compelling interest “outside of the academic context,” leaving possibility diversity justification might be accepted if offered by education institution. Another court seemed to accept “norm of diversity of ideas in the context of academia,” but not “in the context of minority set-aside programs for construction contracts.” S.J. Groves & Sons Co. v. Fulton County, 1993 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19792, at *16 (N.D. Ga. Sept. 30, 1993). D.C. Circuit. Has not addressed diversity justification in education context, but rejected it in context of FCC regulation that required affirmative action in radio station hiring. Court did “not think that diversity [could] be elevated to the ‘compelling’ level, particularly when the [Supreme] Court has given every indication of wanting to cut back Metro Broadcasting.” Lutheran ChurchMissouri Synod v. FCC, 141 F.3d 344 (D.C. Cir. 1998). National Association of College and University Attorneys 12