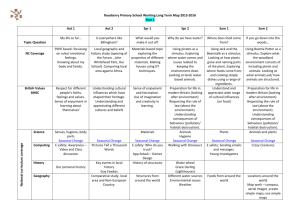

Business Case and Intervention Summary

advertisement