the philadelphia school

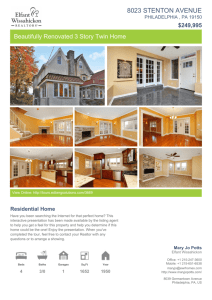

advertisement