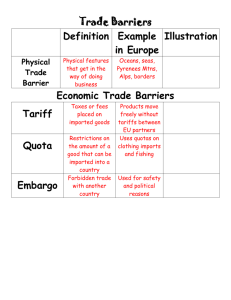

iii. quantitative restrictions

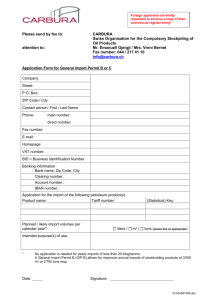

advertisement