Standing-in-the-Court-of-Session-ASLH-Sep-2015-1

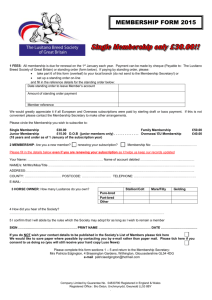

advertisement