The probability of examining human remains as they go through

advertisement

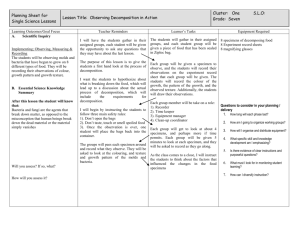

Djuna Elkan 5/12/13 ANTH 485 Taphonomy Write-up The probability of examining human remains as they go through decomposition in undergraduate research is very, very slim. But by getting permission from a local Humboldt resident we were able to obtain a recently deceased felid to observe. We wanted to answer the question: What are the physical changes to a decomposing felid between the months of February and May in Arcata, California? We decided to analyze the soil as well as the decomposition of the flesh itself over this two and a half month period. This paper discusses the process of amateur taphonomy research. When presented with the prospect of studying amateur remains of a cat that had died eight months earlier, Danielle Santos and I decided to do our own project by identifying the stages of decomposition and observing along the way. Methodology The cat that we were given was a friend of ours who was also interested in the research we wanted to do. She gave us full access to do what we wanted to with the remains. After unburying them from a grave that had been dug only eight months earlier, the remains were still wet looking, not very decomposed, and quite smelly. She had placed the remains into a plastic flowerpot to store until our secure pen was set up. Because the yard that we were going to use for our observation had other animals that used it regularly, we wanted to make a fence around the specimen to ensure the safety of our research. It was created with mesh chicken wire shown in our presentation. This made it so we could take pictures and check on the specimen without taking it from the safety of the enclosure. We wanted to place the remains above ground so that we could observe the remains daily and also so they would decompose faster. We decided to take pictures as much as we could, at least every week, if not every day. We would also check the median temperature every week to see if 1 Galloway’s Stages any of our observations correlated with the temperature. By examining this it would give us an idea of what we would see in similar decomposition scenarios during those times of the year. Results After assembling the secure area around the specimen we started to observe it. Our observation started on the 23 of February. The specimen, as said earlier, was not very decomposed at this stage. They appeared very moist, there wasn’t any bone showing yet and smelled very much. Within the first week though we saw some bone exposure of the ulna, radius, some ribs and a white mold began to form. Since it was on the furry part of the remains it probably wasn’t adeposere. We dubbed this stage seven of the Galloway’s stages1. By the third week we started to see some softening of the tissue, which made the bones look more outlined by the flesh still covering them. More bones were becoming visible such as, the right femur, fibula, tibia, some thoracic and lumbar vertebrae were also becoming more noticeable. This pattern continued for several weeks after, the tissue slowly became less abundant while the bones began to be more visible. By week four the vegetation that was growing around the specimen had started to interact with it. The nutrients that the specimen was releasing probably spurred the growth of the plants around it. This also helped because the plants were in need of nutrients so the flesh was becoming less visible in the places where plant life was involved. From weeks five through week eight a strange amount of green discoloration grew around the paws and neck, eventually spreading to the entire abdomen. This we agreed could be because of the amount of rainfall, which will be discussed later. Through this long span of time more bone exposure around the abdomen was becoming more visible, and eventually we agreed by the end of week eight that the specimen was at stage nine of Galloway’s stages. Elkan ANTH 485 Unfortunately a dog got at our research and we ran out of time before our presentation to continue our experiment. We found most of the remains in some grass and were able to determine that some ribs, phalanges, a patella, and some other bones were salvageable. Discussion We found that the climate in February and March was both wet, with a average rain fall of 5.57” and temperatures below 60 degrees.2 This may have made the changes in color on the fur that we saw in the fourth through eighth week of observation. The amount of changes that occurred otherwise was at about the rate that we expected. We were surprised at how long it actually takes for remains that are above ground in a wet environment to fully decompose. It would probably take another few months of warmer weather for the remains to get to at least stage eleven of Galloway’s stages of decomposition. From what we understood the weather has a very large effect on how quickly decomposition occurs. In much dryer climates mummification, as well as, decomposition happen much quicker due to the lack of moisture and the constant sunlight. Because Arcata, CA is a very wet environment with low humidity and high amounts of fog the remains cannot mummify as quickly if at all. In the end we did see more bone exposure, but not to the extent that you would expect to see with this type of experiment if it was dryer. Conclusion Although we could not observe the entire decomposition of these remains, we had the chance too experience how it is done on a much smaller level. We take into consideration that we have not been professionally trained in these techniques, but we have strived to make the best of what we have and what we know. In the beginning of this project we were hoping to have a fully 2 http://www.weather.com/weather/wxclimatology/monthly/graph/95521 skeletonized set of remains by the end of our project. Unfortunately this was not the case. The information that we did gain from the research we did made it easier for us to understand what to do next time we do research like this. Bibliography “Monthly Averages for Arcata, CA”. Weather.com. TRUSTe. Web. 1995-2012. Megyesi, Mary S.; Stephen P. Nawrocki; Neal H. Haskell. Using Accumulated Degree-Days to Estimate the Postmortem Interval from Decomposed Human Remains. Journal of Forensic Science. May 2005. Paper.