Lesson 7 - Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Site

advertisement

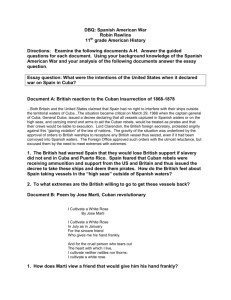

Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit Lesson 7 Title: History of the Caribbean: Fighting for Independence Grade Level: 6 Unit of Study: Caribbean GLCE: G2.2.1 Describe the human characteristics of the region under study (including languages, religion, economic system, governmental system, cultural traditions). G4.4.1 Identify factors that contribute to conflict and cooperation between and among cultural groups (control/use of natural resources, power, wealth, and cultural diversity). G4.1.1 Identify and explain examples of cultural diffusion within the Americas (e.g., baseball, soccer, music, architecture, television, languages, health care, Internet, consumer brands, currency, restaurants, international migration). Time: Approximately 1-3 days (depending on teacher preference for depth of activity) Abstract: In this lesson students will examine the path to independence for Caribbean nations such as Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. Students will also explore today’s Caribbean society, and create a timeline of Caribbean History. Key Concepts: Caribbean nations sought, fought for, and won independence from European rule. Many countries in the Caribbean today have experienced many struggles, but continue to strive for success. Today’s Caribbean culture remains influenced by an ethnic mosaic of peoples which unites all of the islands. Sequence of Activities: 1. Students will investigate the Ten Years War and the Spanish American War and how these wars affected Caribbean life today by reading about them in an encyclopedia or at www.wikipedia.org (see background information at the end of this lesson). 2. Students will use the information they have gathered throughout lessons in this unit so far in order to create a Timeline of Caribbean History. They may create a pencil/paper timeline or a web-based timeline using the following websites: http://www.readwritethink.org/materials/timeline/ http://www.teach-nology.com/web_tools/materials/timeline/ www.ourtimelines.org Connections: Language Arts, Technology, Art Resources http://www.scholars.nus.edu.sg/post/caribbean/nations.html http://www.caribbean-on-line.com/ http://www.caribbean.com/ Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit http://www.caribbeandaily.com/ http://www.cep.unep.org/ Google Earth World Atlas Encyclopedia Textbook (if available) CIA World Fact Book: (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/) www.wikipedia.org Background Information From Wikipedia: Ten Years' War From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ten Years War Date Location Result October 10, 1868–1878 Cuba Spanish victory. Pact of Zanjón Belligerents Cuba Kingdom of Spain Commanders Carlos Manuel de Céspedes Arsenio Martínez Máximo Gómez Campos Antonio Maceo Grajales Strength 12,000 rebels, 40,000 supporters 100,000 Casualties and losses +300,000 rebels and civilian ?? The Ten Years' War (Spanish: Guerra de los Diez Años), (1868-1878), also known as the Great War, began on October 10, 1868 when sugar mill owner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit his followers proclaimed Cuba's independence from Spain. It was the first of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Little War (1879-1880) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895-1898). The final three months of the last conflict escalated to become the Spanish–American War. Background The failure of the latest Reformist efforts, the demise of the "Information Board" and an economic crisis in 1866/67 gave way to a new scenario. In spite of the crisis, the colonial administration continued to make huge profits which were not invested on the island but either went into military expenditures (44% of the revenue), paid for the colonial governments expenses (41%) or sent to Spain and Fernando Poo (12%). The Spaniards with 8% of the population appropriated over 90% of the island’s wealth. In addition, the majority of the Cuban population still had no political rights giving rise to underground movements, especially in the eastern part of the country. [1] In July 1867, the "Revolutionary Committee of Bayamo" was founded under the leadership of a one of Cuba’s wealthiest plantation owners, Francisco Vicente Aguilera. The conspiracy rapidly spread to Oriente’s lager towns, most of all Manzanillo where Carlos Manuel de Céspedes became the main protagonist of the uprising. Originally from Bayamo, Céspedes owned an estate and sugar mill known as ‘’’La Demajagua’’’. The Spanish, aware of Céspedes’ anti-colonial intransigence, tried to force him into submission by imprisoning his son Oscar. Céspedes refused to negotiate and Oscar was executed. [2] Tactics Carlos Manuel de Céspedes The date for the uprising was moved up, because the Spaniards had discovered the plans in early October. In the early morning of October 10 Céspedes issued the independence cry ‘’’10th of October Manifesto’’’ at La Demajagua, starting the war against Spanish rule in Cuba. As a first step, Céspedes freed his slaves, asking them to join the struggle. However, many questioned Céspedes's plans for manumission, notably the rate at which slaves were to be freed, or disagreed with his call for U.S. annexation of Cuba. During the first few days, the uprising almost failed. Céspedes intended to occupy the nearby town of Yara on October 11, from which this revolution took its name, but suffered numerous casualties and was dispersed by a Spanish Army column on the way. Céspedes escaped with only 12 men. The October 10 date is commemorated in Cuba as a national holiday under the name Grito de Yara ("Cry of Yara"). In spite of this defeat, the uprising of Yara was supported in Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit various regions on Oriente and continued to spread throughout the eastern region of Cuba. On October 13, the rebels took eight towns in the province favouring enrolment and acquisition of arms. By the end of October, the insurrection had some 12,000 volunteers. That same month, Máximo Gómez, a former cavalry officer for the Spanish Army in the Dominican Republic, with his extraordinary military skills, taught the Cuban forces what would be their most lethal tactic: the machete charge. [1]. The machete charge was particularly lethal because it involved firearms as well. If the Spanish were caught on the march, the machetes would cut through their ranks. When the Spaniards (following then-standard tactics) formed a square, rifle fire from infantry under cover and pistol and carbine fire from charging cavalry would cause many losses. However, as it would be in wars such as these, yellow fever caused the heaviest losses because the Spanish had not acquired the childhood immunity that the Cuban troops had. Progress of the War The rebels proceeded to seize the important city of Bayamo after a 3-day-combat. It was in the enthusiasm of this victory when the poet and musician, Pedro Figueredo composed Cuba’s national anthem, the “Bayamo”. The first government of the Republic in Arms, headed by Céspedes, was established in Bayamo. The city was retaken by the Spanish after 3 months on January 12, but it had been burned to the ground.[3] Nevertheless, the war spread in Oriente: On November 4, 1868, Camagüey rose up in arms and, in early February1869, Las Villas followed. The uprising was not supported in the westernmost provinces Pinar del Río, Havana and Matanzas and, with few exceptions (Vuelta Abajo) remained clandestine. A staunch supporter of the rebellion was José Martí who, at the age of 16, was detained and condemned to 16 years of hard labour, later deported to Spain and would eventually become a leading Latin American intellectual and Cuba’s foremost national hero as a primary architect of the 1895-98 War of Independence. After some initial victories, and then defeats, Céspedes replaced Gomez with General Thomas Jordan, who brought a well-equipped force, as head of Cuban army. However, General Jordan's regular tactics, although initially effective, left the families of Cuban rebels far too vulnerable to the "ethnic cleansing" tactics of the ruthless Blas Villate, Count of Valmaceda (also spelled Balmaceda). Valeriano Weyler, who would reach notoriety as the "Butcher Weyler" in the 18951898 War, fought along the Count of Balmaceda. General Jordan then left, Máximo Gómez was returned to his command and a new generation of skilled battle-tested Cuban commanders rose from the ranks, these including Antonio Maceo Grajales, José Maceo, and Calixto García and Vicente Garcia González [2]. Other war leaders of note fighting on the Cuban Mambí side included: Donato Mármol, Luis Marcano-Alvarez, Carlos Roloff, Enrique Loret de Mola, Julio Sanguily, Domingo Goicuría, Guillermo Moncada, Quintin Bandera, Benjamín Ramirez, and Julio Grave de Peralta. On April 10, 1869, a constitutional assembly took place in the town of Guáimaro (Camagüey), with the purpose of providing the revolution with greater organizational and juridical unity and with representatives from the areas that had joined the uprising. A major topic of the discussions was whether a centralized leadership should be in charge of both military and civilian affairs or if there should be a separation between civilian government and military leadership, the latter being subordinate to the first. The overwhelming majority voted for the separation option. Céspedes Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit was elected president of this assembly and General Ignacio Agramonte y Loynáz and Antonio Zambrana, principal authors of the proposed Constitution, were elected Secretaries.[4] After completing its work, the Assembly reconstituted itself as the House of Representatives as the state’s supreme power, electing Salvador Cisneros Betancourt as its president, Miguel Gerónimo Gutiérrez as vice-president, and Agramonte and Zambrana as Secretaries. Céspedes was then elected, on April 12, 1869, as the first president of the Republic in Arms and General Manuel de Quesada (who had fought in Mexico under Benito Juárez during the French invasion of that country), as Chief of the Armed Forces. After failing to reach an agreement with the insurrection forces in early 1869, the Spanish responded by unleashing a war of extermination. The colonial government passed several laws: all arrested leaders and collaborators would be executed on the spot, ships carrying weapons would be seized and all on board immediately executed, males 15 and older caught outside of their plantations or places of residence without justification would be summarily executed, all towns were ordered to raise the white flag, otherwise burnt to the ground, any woman caught away from her farm or place of residence would be concentrated in cities. Apart from its own army the government could rely on the Voluntary Corps which had been created a few years earlier to face the announced invasion by Narcisco López and which became notorious for its barbaric and bloody acts. One infamous incident was the execution of eight students from the University of Havana on November 27, 1871. [5] Another one was the seizure of the steamship Virginius in international waters on October 31, 1873 , and, starting on November 4, serial execution of 53 persons, including the captain, most of the crew and a number of Cuban insurgents on board. The serial executions were only stopped by the intervention of a British man-of-war under the command of Sir Lambton Lorraine. In another incident, the so-called "Creciente de Valmaseda", farmers (Guajiros), and the families of Mambises were killed or captured en masse and sent to concentration camps. The Mambises fought using guerrilla warfare and their efforts had much more impact on the eastern side of the island than on the western, due in part to a lack of supplies. Ignacio Agramonte was killed by a stray bullet on May 11, 1873 and was replaced in the command of the central troops by Máximo Gómez. Due to political and personal disagreements and Agramonte's death, the Assembly deposed Céspedes as president, who was replaced by Cisneros. Agramonte had come to realize that his dream Constitution and government were ill suited to the Cuban Republic in Arms, which was the reason he quit as Secretary and assumed command of the Camaguey region. By being curtailed by the Congress, he understood Cespedes' plight, thus becoming a supporter. Céspedes was later surprised and killed by a swift-moving patrol of Spanish troops on February 27, 1874. The new Cuban government had left him with only one escort and denied him permission to leave Cuba for the US, where he wanted to help to prepare and send armed expeditions. Activities in the Ten Years War peaked in the years 1872 and 1873, but after the death of Agramonte and destitution of Céspedes, Cuban operations were limited to the regions of Camagüey and Oriente. Gómez began an invasion of Western Cuba in 1875, but the vast majority of slaves and wealthy sugar producers in the region did not join the revolt. After his most trusted general, the American Henry Reeve, was killed in 1876, the invasion was over. Spain's efforts to fight were hindered by the civil war (Third Carlist War),that broke out in Spain in 1872. When the civil war ended in 1876, more Spanish troops were sent to Cuba until they Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit numbered more than 250.000. The impact of the Spanish measures on the liberation forces was severe. Neither side in the war was able to win a single concrete victory, let alone crush the opposing side to win the war, but in the long run Spain gained the upper hand.[6] [edit] Conclusion of the War From the very onset of the war there were deep divisions with respect its organisation which became even more pronounced after the Assembly of Guáimaro with the dismissal of Céspedes and Quesada in 1873. The Spanish were able to exploit regionalist sentiments and fears that the slaves of Matanzas would break the weak existing balance between whites and blacks. They changed their policy towards the Mambises offering amnesties and reforms. The Mambises did not prevail for a variety of reasons; lack of organization and resources; lower participation by whites; internal racist sabotage (against Maceo and the goals of the Liberating Army); the inability to bring the war to the western provinces (Havana in particular); and opposition by the US government to Cuban independence. The US sold the latest weapons to Spain, but not to the Cuban rebels. [7] Tomás Estrada Palma succeeded Cisneros as president of the Republic in Arms. Estrada Palma was captured by Spanish troops on October 19, 1877. As a result of successive misfortunes, on February 8, 1878, the constitutional organs of the Cuban government were dissolved and negotiations for peace were started in Zanjón, Puerto Príncipe. General Arsenio Martínez Campos, in charge of applying the new policy, arrived in Cuba, but it took him almost two years to convince most of the rebels to accept the Pact of Zanjón on February 10, 1878, signed by a negotiating committee. The document contained most of the promises made by Spain. The Ten Years' War came to an end, except for the resistance of a small group in Oriente led by General Garciá and Antonio Maceo Grajales, who protested in Los Mangos de Baraguá on March 15. Even a constitution and a provisional government was set up but the revolutionary élan was gone. The provisional government convinced Maceo to give up, thus ending the war in May 28, 1878.[8] Many of the graduates of Ten Year War, however, became central players in Cuba's war of independence started in 1895. These include the Maceo brothers, Maximo Gómez, Calixto Garcia and others. [7] The Pact of Zanjón promised various reforms throughout the island which would improve the financial situation of Cuba. Perhaps the most significant was to free all slaves who had fought Spain. A major conflict throughout the war was the abolition of the slavery. Both the rebels and the people loyal to Spain wanted to abolish slavery. In 1880, a law was passed by the Spanish government that freed all of the slaves. However, the slaves were required by law to work for their masters for a number of years but the masters had to pay the slaves for their work. The wages were so low the slaves could barely afford to live off of them. The Spanish government lifted the law before it was to expire because neither the land owners nor the freed men appreciated it. After the war ended, there were 17 years of tension between the people of Cuba and the Spanish government, a time called ‘’’The Rewarding Truce’’’, including the Little War (La Guerra Chiquita) between 1879-1880. These separatists would go on to follow the lead of José Martí, the most passionate of the rebels chose exile over Spanish rule. There was also a severe depression throughout the island. Overall, about 200,000 people lost their lives in the conflict. The war also devastated the coffee industry and American tariffs badly damaged Cuban exports. Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit References 1. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 43 2. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 43-44 3. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 45 4. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 47 5. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 48 6. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 50 7. ^ a b History of Cuba - The Ten Year War 8. ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 52 Perez Jr., Louis A (1988). Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press. Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba. The Challenge of the Yoke and the Star. Editorial SI-MAR S. A., Havana, Cuba, 1998, ISBN 959-7054-19-1 Further reading Portions of this article were extracted from CubaGenWeb. Perhaps the most detailed source for information on the Ten Years' War is still Antonio Pirala's Anales de la Guerra en Cuba, (1895, 1896 and some from 1874) Felipe González Rojas (Editor), Madrid Spanish–American War From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Spanish-American War Part of the Philippine Revolution, Cuban War of Independence Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill by Frederic Remington Date Location Result Territorial changes April 25 – August 12, 1898 Cuba, and Puerto Rico (Carribean) Philippine Islands, and Guam (Asia-Pacific) Treaty of Paris Philippine-American War Spain relinquishes sovereignty over Cuba, cedes the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the United States for the sum of $20 million. Belligerents Kingdom of Spain United States Cuba Philippine Republic Katipunan Cuban and Puerto Rican Loyalists Filipino Loyalists Commanders Patricio Montojo Nelson A. Miles Pascual Cervera William R. Shafter Arsenio Linares George Dewey Manuel Macías y William T. Sampson Casado Máximo Gómez Ramón Blanco y Emilio Aguinaldo Erenas Strength Cuban Republic: 30,000 irregulars[1]:19-20 United States: 300,000 regulars and volunteers[1]:21 208,812 – 278,447 regulars and militia[1]:2021 (Cuba), 10,005 regulars and militia[1] (Puerto Rico), 51,331 regulars and militia[1] (Philippines) Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit Casualties and losses Spanish Navy: Cuban Republic: 10,665 dead [1] United States: 345 dead, 1,645 wounded, 2,565 diseased[1]:67 560 dead, 300–400 wounded<[1]:67 Spanish Army: 6,700 captured,[2]:371 (Philippines) 13,000 diseased[1] (Cuba) The Spanish–American War was an armed military conflict between Spain and the United States that took place between April and August 1898, over the issues of the liberation of Cuba. The war began after American demand for the resolution of the Cuban fight for independence was rejected by Spain. Strong expansionist sentiment in the United States motivated the government to develop a plan for annexation of Spain's remaining overseas territories including the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.[3] The revolution in Havana prompted the United States to send in the warship USS Maine to indicate high national interest. Tension among the American people was raised because of the explosion of the USS Maine, and the yellow journalist newspapers that accused the Spanish of oppression in their colonies, agitating American public opinion. The war ended after victories for the United States in the Philippine Islands and Cuba. On December 10, 1898, the signing of the Treaty of Paris gave the United States control of Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Historical background The Monroe Doctrine[4]of the 19th Century served as the political foundation for the support of the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain in the United States. Cubans had been fighting for self determination, on and off, since the Grito de Yara of 1868. Cuban struggle for independence In 1895, the Spanish colony of Cuba was the site of a small armed uprising against Spanish authority. Financial support for the "Cuba Libre" rebellion came from external organizations, some based in the United States. [2]:2 In 1896, new Captain General for Cuba, General Valeriano Weyler pledged to suppress the insurgency by isolating the rebels from the rest of the population ensuring that the rebels would not receive supplies. By the end of 1897, more than 300,000 Cubans had relocated into Spanish guarded concentration camps. These camps became cesspools of hunger and disease where more than one hundred thousand died.[2]:9 A propaganda war waged in the United States by Cuban émigrés attacked Weyler's inhuman treatment of his countrymen and won the sympathy of broad groups of the U.S. population. Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit Weyler was referred to as a "Butcher" by yellow journalists like William Randolph Hearst. The American newspapers began agitating for intervention with stories of Spanish atrocities against the Cuban population. USS Maine In January 1898, a riot by Cuban volunteers, most of whom were Spanish loyalists, broke out in Havana and led to the destruction of the printing presses of three local newspapers that were critical of General Weyler. These riots prompted the presence of an American Marine force in the island although there had been no attack on Americans during the rioting.[2]:24[5] yet there were still fears for the lives of Americans living in Havana. Concern focused on the pro-Spanish Cubans who harbored resentment of the growing support in the United States for Cuban independence. Washington informed the Consul-General in Havana, Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of Robert E. Lee, that the Maine would be sent to protect United States interests should tensions escalate further. The USS Maine arrived in Havana on January 25, 1898. Her stay was uneventful until the following month. On February 15, 1898, at 9:40 p. m. the Maine sank in Havana Harbor after an explosion, resulting in the deaths of 266 men. The Spanish attributed the event to an internal explosion; but an American inquiry reported that it was caused by a mine; a fact that has been questioned by historians to this day.[who?] Recent investigations have lead to believe that the explosion was indeed caused by an internal infusion of coal combustion and not a land mine.[who?] A total of four USS Maine investigations were conducted into the causes of the explosion, with the investigators coming to different conclusions. The Spanish and American versions would carry on with divergences.[6] A 1999 investigation commissioned by National Geographic Magazine and carried out by Advanced Marine Enterprises concluded that "it appears more probable than was previously concluded that a mine caused the inward bent bottom structure" and the detonation of the ship. However there is still much contention over what caused the explosion.[7] Spanish and loyalist Cuban opinions included a theory that the United States government may have intentionally caused the detonation as a pretext to go to war with Spain.[6][8] Path to war Main article: Propaganda of the Spanish American War Upon the destruction of the Maine,[9] newspaper owners such as William Randolph Hearst came to the conclusion that Spanish officials in Cuba were to blame, and they widely publicized this theory as fact. Their sensationalistic publications fueled American anger by publishing astonishing accounts of "atrocities" committed by Spain in Cuba. A common myth states that Hearst responded to the opinion of his illustrator Frederic Remington, that conditions in Cuba were not bad enough to warrant hostilities with: "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."[10] Lashed to fury, in part by such press, the American cry of the hour became, "Remember the Maine, To Hell with Spain!" President William McKinley, Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed and the business community opposed the growing public demand for war. Senator Redfield Proctor's speech, delivered on March 17, 1898 thoroughly analyzed the situation concluding that war was the only answer. Many in the business and religious communities, which had heretofore opposed war, switched sides, leaving President McKinley Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit and Speaker Reed almost alone in their opposition to the war.[11] On April 11 President McKinley asked Congress for authority to send American troops to Cuba for the purpose of ending the civil war there. On April 19, while Congress was considering joint resolutions supporting Cuban independence, Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado proposed the Teller amendment to ensure that the United States would not establish permanent control over Cuba following the cessation of hostilities with Spain. The amendment, disclaiming any intention to annex Cuba passed Senate 42 to 35; the House concurred the same day, 311 to 6. The amended resolution demanded Spanish withdrawal and authorized the president to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuba gain independence from Spain. President McKinley signed the joint resolution on April 20, 1898, and the ultimatum was forwarded to Spain. In response, Spain broke off diplomatic relations with the United States and declared war on April 23. On April 25, Congress declared that a state of war between the United States and Spain had existed since April 20 (later changed to April 21).[12] Theaters of operations Pacific Philippines The Spanish had first discovered the Philippines on March 17, 1521. Ever since then they had been a key holding for the Spanish Empire. The first battle between American and Spanish forces was at Manila Bay where, on May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey, commanding the United States Navy's Asiatic Squadron aboard the USS Olympia, in a matter of hours, defeated the Spanish squadron under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón. Dewey managed this with only nine wounded.[13][14] With the German seizure of Tsingtao in 1897, Dewey's Squadron had become the only naval force in the Far East without a local base of its own, and was beset with coal and ammunition problems.[15] Despite these logistical problems, the Asiatic squadron had not only destroyed the Spanish fleet but had also captured the harbor of Manila.[15] Following Dewey's victory, Manila Bay was filled with the warships of Great Britain, Germany, France, and Japan; all of which outgunned Dewey's force.[15] The German fleet of eight ships, ostensibly in Philippine waters to protect German interests (a single import firm), acted provocatively—cutting in front of American ships, refusing to salute the United States flag (according to customs of naval courtesy), taking soundings of the harbor, and landing supplies for the besieged Spanish. The Germans, with interests of their own, were eager to take advantage of whatever opportunities the conflict in the islands might afford. The Americans called the bluff of the Germans, threatening conflict if the aggressive activities continued, and the Germans backed down.[16][17] Commodore Dewey had transported Emilio Aguinaldo to the Philippines from exile in Hong Kong in order to rally Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government.[18] U.S. land forces and the Filipinos had taken control of most of the islands by June, except for the walled city of Intramuros and, on June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo had declared the independence of the Philippines.[19] Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit On August 13, with American commanders unaware that the cease fire had been signed between Spain and the United States on the previous day, American forces captured the city of Manila from the Spanish.[20] [21] This battle marked an end of Filipino-American collaboration, as Filipino forces were prevented from entering the captured city of Manila, an action which was deeply resented by the Filipinos and which later led to the Philippine–American War.[22] Guam On June 20, 1898, a U.S. fleet commanded by Captain Henry Glass, consisting of the cruiser USS Charleston and three transports carrying troops to the Philippines entered Guam's Apia Harbor, Captain Glass having opened sealed orders instructing him to proceed to Guam and capture it. The Charleston fired a few cannon rounds at Fort Santa Cruz without receiving any return fire. Two local officials, not knowing that war had been declared and, being under the misapprehension that the firing had been a salute, came out to the Charleston to apologize for their inability to return the salute. Glass informed them that the United States and Spain were at war. The following day, Glass sent Lt. William Braunersruehter to meet the Spanish Governor to arrange the surrender of the island and the Spanish garrison there. 54 Spanish infantry were captured and transported to the Philippines as prisoners of war. No U.S. forces were left on Guam, but the only U.S. citizen on the island, Frank Portusach, told Captain Glass that he would look after things until U.S. forces returned.[23] The Caribbean Cuba Spanish armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón. Destroyed during the Battle of Santiago on 3 July 1898. Detail from Charge of the 24th and 25th Colored Infantry and Rescue of Rough Riders at San Juan Hill, July 2, 1898 depicting the Battle of San Juan Hill. Theodore Roosevelt actively encouraged intervention in Cuba and, while assistant secretary of the Navy, placed the Navy on a war-time footing and prepared Dewey's Asiatic Squadron for battle. He worked with Leonard Wood in convincing the Army to raise an all-volunteer regiment, Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. Wood was given command of the regiment that quickly became known as the "Rough Riders".[24] The Americans planned to capture the city of Santiago de Cuba in order to destroy Linares' army and Cervera's fleet. To reach Santiago they had to pass through concentrated Spanish defenses in the San Juan Hills and a small town in El Caney. The American forces were aided in Cuba by the pro-independence rebels led by General Calixto García. Land campaign Between June 22 and June 24, the U.S. V Corps under General William R. Shafter landed at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and established the American base of operations. A contingent of Spanish troops, having fought a skirmish with the Americans near Siboney on June 23, had retired to their lightly entrenched positions at Las Guasimas. An advance guard of U.S. forces under former Confederate General Joseph Wheeler ignored Cuban scouting parties and orders to proceed with caution. They caught up with and engaged the Spanish rear guard who effectively ambushed them, in the Battle of Las Guasimas on June 24. The battle ended indecisively in favor of Spain and the Spanish left Las Guasimas on their planned retreat to Santiago. The U.S. army employed American Civil War-era skirmishers at the head of the advancing columns. All four U.S. soldiers who had volunteered to act as skirmishers walking point at head of the American column were killed, including Hamilton Fish, from a well-known patrician New York City family and Captain Alyn Capron, whom Theodore Roosevelt would describe as one of the finest natural leaders and soldiers he ever met. The Battle of Las Guasimas showed the U.S. that the old linear Civil War tactics did not work effectively against Spanish troops who had learned the art of cover and concealment from their own struggle with Cuban insurgents, and never made the error of revealing their positions while on the defense. The Spaniards were also aided by the then new smokeless powder, which also helped them to remain concealed while firing. American soldiers were only able to advance against the Spaniards in what are now called "fireteam" rushes, four-to-five man groups advancing while others laid down supporting fire. On July 1, a combined force of about 15,000 American troops in regular infantry, cavalry and volunteer regiments, including Roosevelt and his "Rough Riders", notably the 71st New York, 1st North Carolina, 23rd and 24th Colored, and rebel Cuban forces attacked 1,270 entrenched Spaniards in dangerous Civil War style frontal assaults at the Battle of El Caney and Battle of San Juan Hill outside of Santiago.[25] More than 200 U.S. soldiers were killed and close to 1,200 wounded in the fighting.[26] Supporting fire by Gatling guns was critical to the success of the assault.[27][28] Cervera decided to escape Santiago two days later. The Spanish forces at Guantánamo were so isolated by Marines and Cuban forces that they did not know that Santiago was under siege, and their forces in the northern part of the province could not break through Cuban lines. This was not true of the Escario relief column from Manzanillo,[29] which fought its way past determined Cuban resistance but arrived too late to participate in the siege. After the battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney, the American advance ground to a halt. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, allowing them to stabilize their line and bar the entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans forcibly began a bloody, strangling siege of the city.[30] Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit During the nights, Cuban troops dug successive series of "trenches" (actually raised parapets), toward the Spanish positions. Once completed, these parapets were occupied by U.S. soldiers and a new set of excavations went forward. American troops, while suffering daily losses from Spanish fire and sniper rifles, suffered far more casualties from heat exhaustion and mosquitoborne disease.[31] At the western approaches to the city, Cuban general Calixto Garcia began to encroach on the city, causing much panic and fear of reprisals among the Spanish forces. The Americans planned to capture the city of Santiago de Cuba in order to destroy Linares' army and Cervera's fleet. To reach Santiago they had to pass through concentrated Spanish defenses in the San Juan Hills and a small town in El Caney. Naval operations The major port of Santiago de Cuba was the main target of naval operations during the war. The U.S. fleet attacking Santiago needed shelter from the summer hurricane season. Thus Guantánamo Bay with its excellent harbor was chosen for this purpose. The 1898 invasion of Guantánamo Bay happened June 6–10, with the first U.S. naval attack and subsequent successful landing of U.S. Marines with naval support. The Battle of Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898, was the largest naval engagement of the Spanish-American War and resulted in the destruction of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron (also known as the Flota de Ultramar). In May 1898, the fleet of Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete, had been spotted by American forces in Santiago Harbor where they had taken shelter for protection from sea attack. A two month stand-off between Spanish and American naval forces followed. When the Spanish squadron finally attempted to leave the harbor on July 3, the American forces destroyed or grounded five of the six ships. Only one Spanish vessel, the speedy new armored cruiser Cristobal Colón, survived, but her captain hauled down his flag and scuttled her when the Americans finally caught up with her. The 1,612 Spanish sailors captured, including Admiral Cervera, were sent to Seavey's Island at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, where they were confined at Camp Long as prisoners of war from July 11 until mid-September. During the stand-off, United States Assistant Naval Constructor Richmond Pearson Hobson had been ordered by Rear Admiral William T. Sampson to sink the collier Merrimac in the harbor to bottle up the Spanish fleet. The mission was a failure, and Hobson and his crew were captured. They were exchanged on July 6, and Hobson became a national hero; he received the Medal of Honor in 1933 and became a Congressman. Puerto Rico Main article: Puerto Rican Campaign Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit U.S. 1st Kentucky Volunteers in Puerto Rico, 1898. During May 1898, Lt. Henry H. Whitney of the United States Fourth Artillery was sent to Puerto Rico on a reconnaissance mission, sponsored by the Army's Bureau of Military Intelligence. He provided maps and information on the Spanish military forces to the U.S. government prior to the invasion. On May 10, U.S. Navy warships were sighted off the coast of Puerto Rico. On May 12, a squadron of 12 U.S. ships commanded by Rear Adm. William T. Sampson bombarded San Juan. During the bombardment, many government buildings were shelled. On June 25, the Yosemite blockaded San Juan harbor. On July 25, General Nelson A. Miles, with 3,300 soldiers, landed at Guánica, beginning the Puerto Rican Campaign. The troops encountered resistance early in the invasion. The first skirmish between the American and Spanish troops occurred in Guanica. The first organized armed opposition occurred in Yauco in what became known as the Battle of Yauco.[32] This encounter was followed by the Battles of Fajardo, Guayama, Guamani River Bridge, Coamo, Silva Heights and finally by the Battle of Asomante.[32][33] On August 9, 1898, infantry and cavalry troops encountered Spanish and Puerto Rican soldiers armed with cannons in a mountain known as Cerro Gervasio del Asomante, while attempting to enter Aibonito.[33] The American commanders decided to retreat and regroup, returning on August 12, 1898, with an artillery unit.[33] The Spanish and Puerto Rican units began the offensive with cannon fire, being led by Ricardo Hernáiz. The sudden attack caused confusion among some soldiers, who reported seeing a second Spanish unit nearby.[33] In the crossfire, four American troops — Sargeant John Long, Lieutenant Harris, Captain E.T. Lee and Corporal Oscar Sawanson — were gravely injured.[33] Based on this and the reports of upcoming reinforcements, Commander Landcaster ordered a retreat.[33] All military action in Puerto Rico was suspended later that night, after the signing of the Treaty of Paris was made public. Peace treaty With defeats in Cuba and the Philippines, and both of its fleets incapacitated, Spain sued for peace. Hostilities were halted on August 12, 1898, with the signing in Washington of a Protocol of Peace between the United States and Spain.[34] The formal peace treaty was signed in Paris on December 10, 1898, and was ratified by the United States Senate on February 6, 1899. It came into force on April 11, 1899. Cubans participated only as observers. The United States gained almost all of Spain's colonies, including the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Cuba, having been occupied as of July 17, 1898, and thus under the jurisdiction of the United States Military Government (USMG), formed its own civil government and attained independence on May 20, 1902, with the announced end of USMG jurisdiction over the island. However, the United States imposed various restrictions on the new government, including prohibiting alliances with other countries, and reserved for itself the right of intervention. The US also established a perpetual lease of Guantanamo Bay. On August 14, 1898, 11,000 ground troops were sent to occupy the Philippines. When U.S. troops began to take the place of the Spanish in control of the country, warfare broke out between U.S. forces and the Filipinos resulting in the Philippine-American War. Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit Aftermath With the end of the war, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt musters out of the U.S. Army after the required 30 day quarantine period at Montauk, Long Island, in 1898. The war lasted only four months. Ambassador (later Secretary of State) John Hay, writing from London to his friend Theodore Roosevelt declared that from start to finish it had been “a splendid little war”.[35][36] The press showed Northerners and Southerners, blacks and whites fighting against a common foe, helping to ease the scars left from the American Civil War. The war marked American entry into world affairs. Ever since, the United States has had a significant hand in various conflicts around the world, and entered into many treaties and agreements. The Panic of 1893 was over by this point, and the United States entered a lengthy and prosperous period of high economic growth, population growth, and technological innovation which lasted through the 1920s.[37] The war marked the effective end of the Spanish empire in Asia, Oceania and the Americas. Spain had been declining as an Imperial power since the early 19th century as a result of Napoleon's invasion. The defeat caused a national trauma because of the affinity of peninsular Spaniards with Cuba, which was seen as another province of Spain rather than as a colony. Only a handful of territories remained of Spain's overseas holdings (e.g., Spanish West Africa, Spanish Guinea, Spanish Sahara,Spanish Morocco, Canary Islands). The Spanish military man Julio Cervera Baviera, involved in the Puerto Rican Campaign, blamed the natives of that colony for its occupation by the Americans: "I have never seen such a servile, ungrateful country [i.e. Puerto Rico]... In twenty-four hours, the people of Puerto Rico went from being fervently Spanish to enthusiastically American... They humiliated themselves, giving in to the invader as the slave bows to the powerful lord."[38] He was challenged to a duel by a group of young Puerto Ricans for writing this pamphlet.[39] Culturally a new wave called the Generation of 1898 originated as a response to this trauma, marking a renaissance of the Spanish culture. Economically, the war actually benefited Spain, because after the war, large sums of capital held by Spaniards not only in Cuba but also all over America were brought back to the peninsula and invested in Spain. This massive flow of capital (equivalent to 25% of the gross domestic product of one year) helped to develop the large modern firms in Spain in industrial sectors (steel, chemical, mechanical, textiles and shipyards Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit among others), in the electrical power industry and in the financial sector.[40] However, the political consequences were serious. The defeat in the war began the weakening of the fragile political stability that had been established earlier by the rule of Alfonso XII. The cover of Puck from April 6, 1901. Caricaturizes an Easter bonnet made out of a warship that alludes to the gains of the Spanish-American War. Congress had passed the Teller Amendment prior to the war, promising Cuban independence. However, the Senate passed the Platt Amendment as a rider to an Army appropriations bill, forcing a peace treaty on Cuba which prohibited it from signing treaties with other nations or contracting a public debt. The Platt Amendment was pushed by imperialists who wanted to project U.S. power abroad (this was in contrast to the Teller Amendment which was pushed by anti-imperialists who called for a restraint on U.S. hegemony). The amendment granted the United States the right to stabilize Cuba militarily as needed. The Platt Amendment also provided for the establishment of a permanent American naval base in Cuba. Guantánamo Bay was established after the signing of treaties between Cuba and the US beginning in 1903. The United States annexed the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. The notion of the United States as an imperial power, with colonies, was hotly debated domestically with President McKinley and the Pro-Imperialists winning their way over vocal opposition led by Democrat William Jennings Bryan, who had supported the war. The American public largely supported the possession of colonies, but there were many outspoken critics such as Mark Twain, who wrote The War Prayer in protest. Roosevelt returned to the United States a war hero, and he was soon elected governor and then vice president. Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit 1900 Campaign poster. The war served to further cement relations between the American North and South. The war gave both sides a common enemy for the first time since the end of the Civil War in 1865, and many friendships were formed between soldiers of both northern and southern states during their tours of duty. This was an important development since many soldiers in this war were the children of Civil War veterans on both sides.[41] Segregation in the U.S. Military, 1898. The African-American community strongly supported the rebels in Cuba, supported entry into the war, and gained prestige from their wartime performance in the Army. Spokesmen noted that 33 African-American seamen had died in the Maine explosion. The most influential Black leader, Booker T. Washington, argued that his race was ready to fight. War offered them a chance "to render service to our country that no other race can", because, unlike Whites, they were "accustomed" to the "peculiar and dangerous climate" of Cuba. One of the Black units that served in the war was the 9th Cavalry Regiment. In March 1898, Washington promised the Secretary of the Navy that war would be answered by "at least ten thousand loyal, brave, strong Black men in the south who crave an opportunity to show their loyalty to our land, and would gladly take this method of showing their gratitude for the lives laid down, and the sacrifices made, that Blacks might have their freedom and rights."[42] In 1904, the United Spanish War Veterans was created from smaller groups of the veterans of the Spanish American War. Today, that organization is defunct, but it left an heir in the form of the Sons of Spanish American War Veterans, created in 1937 at the 39th National Encampment of the United Spanish War Veterans. According to data from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the last surviving U.S. veteran of the conflict, Nathan E. Cook, died on September 10, 1992, at age 106. (If the data are to be believed, Cook, born October 10, 1885, would have been only 12 years old when he served in the war.) Finally, in an effort to pay the costs of the war, Congress passed an excise tax on long-distance phone service.[43] At the time, it affected only wealthy Americans who owned telephones. However, the Congress neglected to repeal the tax after the war ended four months later, and the tax remained in place for over 100 years until, on August 1, 2006, it was announced that the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the IRS would no longer collect the tax.[44] Spanish-American War in film and television The Rough Riders, a 1927 silent film Rough Riders, a 1997 television mini-series directed by John Milius, and featuring Tom Berenger (Theodore Roosevelt), Gary Busey (Joseph Wheeler), Sam Elliott (Bucky Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project Sixth Grade Caribbean Unit O'Neill), Dale Dye (Leonard Wood), Brian Keith (William McKinley), George Hamilton (William Randolph Hearst), and R. Lee Ermey (John Hay) The Spanish-American War: First Intervention, a 2007 docudrama from The History Channel Calhoun ISD Social Studies Curriculum Design Project