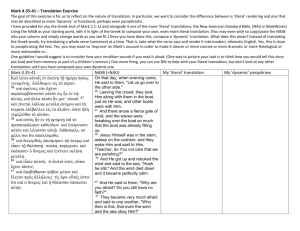

Morton2012. - University of Edinburgh

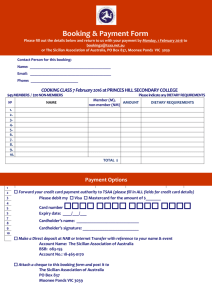

advertisement