MSWord Version of Topics Related to Decision Making

advertisement

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 – What is Decision making?

2

Chapter 2 – Decision theory

8

Chapter 3 – Emotions in Decision Making

13

Chapter 4 – Risk

18

Chapter 5 – Risk management

31

Chapter 6 – Responsible decision making

42

Chapter 7 – Behavioral Decision Making

47

Webliography

56

Chapter 1

What is

Decision

making?

Decision making can be regarded as an outcome of mental processes (cognitive process) leading to the

selection of a course of action among several alternatives. Every decision making process produces a

final choice.[1] The output can be an action or an opinion of choice.

Contents

* 1 Overview

* 2 Decision making processes topics

o 2.1 Cognitive and personal biases

o 2.2 Neuroscience perspective

* 3 Styles and methods of decision making

* 4 See also

* 5 References

* 6 Further reading

* 7 External links

Overview

Human performance in decision making terms has been subject of active research from several

perspectives. From a psychological perspective, it is necessary to examine individual decisions in the

context of a set of needs, preferences an individual has and values he/she seeks. From a cognitive

perspective, the decision making process must be regarded as a continuous process integrated in the

interaction with the environment. From a normative perspective, the analysis of individual decisions is

concerned with the logic of decision making and rationality and the invariant choice it leads to.[2]

Yet, at another level, it might be regarded as a problem solving activity which is terminated when a

satisfactory solution is found. Therefore, decision making is a reasoning or emotional process which can

be rational or irrational, can be based on explicit assumptions or tacit assumptions.

Logical decision making is an important part of all science-based professions, where specialists apply

their knowledge in a given area to making informed decisions. For example, medical decision making

often involves making a diagnosis and selecting an appropriate treatment. Some research using

naturalistic methods shows, however, that in situations with higher time pressure, higher stakes, or

increased ambiguities, experts use intuitive decision making rather than structured approaches,

following a recognition primed decision approach to fit a set of indicators into the expert's experience

and immediately arrive at a satisfactory course of action without weighing alternatives. Also, recent

robust decision efforts have formally integrated uncertainty into the decision making process.

Decision making processes topics

According to behavioralist Isabel Briggs Myers, a person's decision making process depends on a

significant degree on their cognitive style.[3] Myers developed a set of four bi-polar dimensions, called

the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). The terminal points on these dimensions are: thinking and

feeling; extroversion and introversion; judgment and perception; and sensing and intuition. She claimed

that a person's decision making style is based largely on how they score on these four dimensions. For

example, someone who scored near the thinking, extroversion, sensing, and judgment ends of the

dimensions would tend to have a logical, analytical, objective, critical, and empirical decision making

style.

Other studies suggest that these national or cross-cultural differences exist across entire societies. For

example, Maris Martinsons has found that American, Japanese and Chinese business leaders each

exhibit a distinctive national style of decision making.[4]

Cognitive and personal biases

Some of the decision making techniques that we use in everyday life include:

* listing the advantages and disadvantages of each option, popularized by Plato and Benjamin Franklin

* flipping a coin, cutting a deck of playing cards, and other random or coincidence methods

* accepting the first option that seems like it might achieve the desired result

* prayer, tarot cards, astrology, augurs, revelation, or other forms of divination

* acquiesce to a person in authority or an "expert"

* calculating the expected value or utility for each option.

For example, a person is considering two jobs. At the first job option the person has a 60% chance of

getting a 30% raise in the first year. And at the second job option the person has an 80% chance of

getting a 10% raise in the first year. The decision maker would calculate the expected value of each

option, calculating the probability multiplied by the increase of value. (0.60*0.30=0.18 [option a]

0.80*0.10=0.08 [option b]) The person deciding on the job would chose the option with the highest

expected value, in this example option number one. An alternative may be to apply one of the processes

described below, in particular in the Business and Management section.

Biases can creep into our decision making processes. Many different people have made a decision about

the same question (e.g. "Should I have a doctor look at this troubling breast cancer symptom I've

discovered?" "Why did I ignore the evidence that the project was going over budget?") and then craft

potential cognitive interventions aimed at improving decision making outcomes.

Below is a list of some of the more commonly debated cognitive biases.

* Selective search for evidence (a.k.a. Confirmation bias in psychology) (Scott Plous, 1993) - We tend

to be willing to gather facts that support certain conclusions but disregard other facts that support

different conclusions.

* Premature termination of search for evidence - We tend to accept the first alternative that looks like

it might work.

* Inertia - Unwillingness to change thought patterns that we have used in the past in the face of new

circumstances.

* Selective perception - We actively screen-out information that we do not think is salient. (See

prejudice.)

* Wishful thinking or optimism bias - We tend to want to see things in a positive light and this can

distort our perception and thinking.

* Choice-supportive bias occurs when we distort our memories of chosen and rejected options to

make the chosen options seem relatively more attractive.

* Recency - We tend to place more attention on more recent information and either ignore or forget

more distant information. (See semantic priming.) The opposite effect in the first set of data or other

information is termed Primacy effect (Plous, 1993).

* Repetition bias - A willingness to believe what we have been told most often and by the greatest

number of different of sources.

* Anchoring and adjustment - Decisions are unduly influenced by initial information that shapes our

view of subsequent information.

* Group think - Peer pressure to conform to the opinions held by the group.

* Source credibility bias - We reject something if we have a bias against the person, organization, or

group to which the person belongs: We are inclined to accept a statement by someone we like. (See

prejudice.)

* Incremental decision making and escalating commitment - We look at a decision as a small step in a

process and this tends to perpetuate a series of similar decisions. This can be contrasted with zerobased decision making. (See slippery slope.)

* Attribution asymmetry - We tend to attribute our success to our abilities and talents, but we

attribute our failures to bad luck and external factors. We attribute other's success to good luck, and

their failures to their mistakes.

* Role fulfillment (Self Fulfilling Prophecy) - We conform to the decision making expectations that

others have of someone in our position.

* Underestimating uncertainty and the illusion of control - We tend to underestimate future

uncertainty because we tend to believe we have more control over events than we really do. We believe

we have control to minimize potential problems in our decisions.

] Neuroscience perspective

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and orbitofrontal cortex are brain regions involved in decision

making processes. A recent neuroimaging study, Interactions between decision making and

performance monitoring within prefrontal cortex, found distinctive patterns of neural activation in these

regions depending on whether decisions were made on the basis of personal volition or following

directions from someone else.

Another recent study by Kennerly, et al. (2006) found that lesions to the ACC in the macaque resulted in

impaired decision making in the long run of reinforcement guided tasks suggesting that the ACC is

responsible for evaluating past reinforcement information and guiding future action.

Emotion appears to aid the decision making process:

* Decision making often occurs in the face of uncertainty about whether one's choices will lead to

benefit or harm (see also Risk). The somatic-marker hypothesis is a neurobiological theory of how

decisions are made in the face of uncertain outcome. This theory holds that such decisions are aided by

emotions, in the form of bodily states, that are elicited during the deliberation of future consequences

and that mark different options for behavior as being advantageous or disadvantageous. This process

involves an interplay between neural systems that elicit emotional/bodily states and neural systems that

map these emotional/bodily states. [http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.14678721.2006.00448.x?cookieSet=1&journalCode=cdir

Styles and methods of decision making

Styles and methods of decision making were elaborated by the founder of Predispositioning Theory,

Aron Katsenelinboigen. In his analysis on styles and methods Katsenelinboigen referred to the game of

chess, saying that “chess does disclose various methods of operation, notably the creation of

predisposition—methods which may be applicable to other, more complex systems.”[5]

In his book Katsenelinboigen states that apart from the methods (reactive and selective) and submethods (randomization, predispositioning, programming), there are two major styles – positional and

combinational. Both styles are utilized in the game of chess. According to Katsenelinboigen, the two

styles reflect two basic approaches to the uncertainty: deterministic (combinational style) and

indeterministic (positional style). Katsenelinboigen’s definition of the two styles are the following.

The combinational style is characterized by

a very narrow, clearly defined, primarily material goal, and

a program that links the initial position with the final outcome.

In defining the combinational style in chess, Katsenelinboigen writes:

The combinational style features a clearly formulated limited objective, namely the capture of

material (the main constituent element of a chess position). The objective is implemented via a

well defined and in some cases in a unique sequence of moves aimed at reaching the set goal.

As a rule, this sequence leaves no options for the opponent. Finding a combinational objective

allows the player to focus all his energies on efficient execution, that is, the player’s analysis

may be limited to the pieces directly partaking in the combination. This approach is the crux of

the combination and the combinational style of play.[5]

The positional style is distinguished by

a positional goal and

a formation of semi-complete linkages between the initial step and final outcome.

“Unlike the combinational player, the positional player is occupied, first and foremost, with the

elaboration of the position that will allow him to develop in the unknown future. In playing the

positional style, the player must evaluate relational and material parameters as independent

variables. ( … ) The positional style gives the player the opportunity to develop a position until it

becomes pregnant with a combination. However, the combination is not the final goal of the

positional player—it helps him to achieve the desirable, keeping in mind a predisposition for

the future development. The Pyrrhic victory is the best example of one’s inability to think

positionally.”[6]

The positional style serves to

a) create a predisposition to the future development of the position;

b) induce the environment in a certain way;

c) absorb an unexpected outcome in one’s favor;

d) avoid the negative aspects of unexpected outcomes.

The positional style gives the player the opportunity to develop a position until it becomes

pregnant with a combination. Katsenelinboigen writes:

“As the game progressed and defense became more sophisticated the combinational style of

play declined. . . . The positional style of chess does not eliminate the combinational one with

its attempt to see the entire program of action in advance. The positional style merely prepares

the transformation to a combination when the latter becomes feasible.”

Chapter 2

Decision theory

Normative and descriptive decision theory

Most of decision theory is normative or prescriptive, i.e. it is concerned with identifying the

best decision to take, assuming an ideal decision maker who is fully informed, able to compute

with perfect accuracy, and fully rational. The practical application of this prescriptive approach

(how people should make decisions) is called decision analysis, and aimed at finding tools,

methodologies and software to help people make better decisions. The most systematic and

comprehensive software tools developed in this way are called decision support systems.

Since it is obvious that people do not typically behave in optimal ways, there is also a related

area of study, which is a positive or descriptive discipline, attempting to describe what people

will actually do. Since the normative, optimal decision often creates hypotheses for testing

against actual behaviour, the two fields are closely linked. Furthermore it is possible to relax the

assumptions of perfect information, rationality and so forth in various ways, and produce a

series of different prescriptions or predictions about behaviour, allowing for further tests of the

kind of decision-making that occurs in practice.

What kinds of decisions need a theory?

Choice between incommensurable commodities

Choice under uncertainty

This area represents the heart of decision theory. The procedure now referred to as expected

value was known from the 17th century. Blaise Pascal invoked it in his famous wager (see

below), which is contained in his Pensées, published in 1670. The idea of expected value is that,

when faced with a number of actions, each of which could give rise to more than one possible

outcome with different probabilities, the rational procedure is to identify all possible outcomes,

determine their values (positive or negative) and the probabilities that will result from each

course of action, and multiply the two to give an expected value. The action to be chosen

should be the one that gives rise to the highest total expected value. In 1738, Daniel Bernoulli

published an influential paper entitled Exposition of a New Theory on the Measurement of Risk,

in which he uses the St. Petersburg paradox to show that expected value theory must be

normatively wrong. He also gives an example in which a Dutch merchant is trying to decide

whether to insure a cargo being sent from Amsterdam to St Petersburg in winter, when it is

known that there is a 5% chance that the ship and cargo will be lost. In his solution, he defines a

utility function and computes expected utility rather than expected financial value.

In the 20th century, interest was reignited by Abraham Wald's 1939 paper[1] pointing out that

the two central concerns of orthodox statistical theory at that time, namely statistical

hypothesis testing and statistical estimation theory, could both be regarded as particular special

cases of the more general decision problem. This paper introduced much of the mental

landscape of modern decision theory, including loss functions, risk functions, admissible

decision rules, a priori distributions, Bayes decision rules, and minimax decision rules. The

phrase "decision theory" itself was first used in 1950 by E. L. Lehmann.[citation needed]

The rise of subjective probability theory, from the work of Frank Ramsey, Bruno de Finetti,

Leonard Savage and others, extended the scope of expected utility theory to situations where

only subjective probabilities are available. At this time it was generally assumed in economics

that people behave as rational agents and thus expected utility theory also provided a theory of

actual human decision-making behaviour under risk. The work of Maurice Allais and Daniel

Ellsberg showed that this was clearly not so. The prospect theory of Daniel Kahneman and

Amos Tversky placed behavioural economics on a more evidence-based footing. It emphasized

that in actual human (as opposed to normatively correct) decision-making "losses loom larger

than gains", people are more focused on changes in their utility states than the states

themselves and estimation of subjective probabilities is severely biased by anchoring.

Castagnoli and LiCalzi (1996),[citation needed] Bordley and LiCalzi (2000)[citation needed] recently showed

that maximizing expected utility is mathematically equivalent to maximizing the probability that

the uncertain consequences of a decision are preferable to an uncertain benchmark (e.g., the

probability that a mutual fund strategy outperforms the S&P 500 or that a firm outperforms the

uncertain future performance of a major competitor.). This reinterpretation relates to

psychological work suggesting that individuals have fuzzy aspiration levels (Lopes &

Oden),[citation needed] which may vary from choice context to choice context. Hence it shifts the

focus from utility to the individual's uncertain reference point.

Pascal's Wager is a classic example of a choice under uncertainty. The uncertainty, according to

Pascal, is whether or not God exists. Belief or non-belief in God is the choice to be made.

However, the reward for belief in God if God actually does exist is infinite. Therefore, however

small the probability of God's existence, the expected value of belief exceeds that of non-belief,

so it is better to believe in God. (There are several criticisms of the argument.)

Intertemporal choice

This area is concerned with the kind of choice where different actions lead to outcomes that

are realised at different points in time. If someone received a windfall of several thousand

dollars, they could spend it on an expensive holiday, giving them immediate pleasure, or they

could invest it in a pension scheme, giving them an income at some time in the future. What is

the optimal thing to do? The answer depends partly on factors such as the expected rates of

interest and inflation, the person's life expectancy, and their confidence in the pensions

industry. However even with all those factors taken into account, human behavior again

deviates greatly from the predictions of prescriptive decision theory, leading to alternative

models in which, for example, objective interest rates are replaced by subjective discount rates.

Competing decision makers

Some decisions are difficult because of the need to take into account how other people in the

situation will respond to the decision that is taken. The analysis of such social decisions is the

business of game theory, and is not normally considered part of decision theory, though it is

closely related. In the emerging socio-cognitive engineering the research is especially focused

on the different types of distributed decision-making in human organizations, in normal and

abnormal/emergency/crisis situations. The signal detection theory is based on the Decision

theory.

Complex decisions

Other areas of decision theory are concerned with decisions that are difficult simply because of

their complexity, or the complexity of the organization that has to make them. In such cases the

issue is not the deviation between real and optimal behaviour, but the difficulty of determining

the optimal behaviour in the first place. The Club of Rome, for example, developed a model of

economic growth and resource usage that helps politicians make real-life decisions in complex

situations.

Paradox of choice

Observed in many cases is the paradox that more choices may lead to a poorer decision or a

failure to make a decision at all. It is sometimes theorized to be caused by analysis paralysis,

real or perceived, or perhaps from rational ignorance. A number of researchers including

Sheena S. Iyengar and Mark R. Lepper have published studies on this phenomenon.[2] A

popularization of this analysis was done by Barry Schwartz in his 2004 book, The Paradox of

Choice.

Statistical decision theory

Several statistical tools and methods are available to organize evidence, evaluate risks, and aid

in decision making. The risks of Type I and type II errors can be quantified (estimated

probability, cost, expected value, etc) and rational decision making is improved.

Alternatives to probability theory

A highly controversial issue is whether one can replace the use of probability in decision theory

by other alternatives. The proponents of fuzzy logic, possibility theory, Dempster-Shafer theory

and info-gap decision theory maintain that probability is only one of many alternatives and

point to many examples where non-standard alternatives have been implemented with

apparent success. Work by Yousef and others advocate exotic probability theories using

complex-valued functions based on the probability amplitudes developed and validated by

Birkhoff and Von Neumann in quantum physics.

Advocates of probability theory point to:

the work of Richard Threlkeld Cox for justification of the probability axioms,

the Dutch book paradoxes of Bruno de Finetti as illustrative of the theoretical difficulties that

can arise from departures from the probability axioms, and

the complete class theorems which show that all admissible decision rules are equivalent to a

Bayesian decision rule with some prior distribution (possibly improper) and some utility

function. Thus, for any decision rule generated by non-probabilistic methods, either there is an

equivalent rule derivable by Bayesian means, or there is a rule derivable by Bayesian means

which is never worse and (at least) sometimes better.

Chapter 3

Emotions in

Decision

Making

One of the most common theories in the field of decision making is the expected utility theory

(EU). According to this theory, people usually make their decisions by weighing the severity and

likelihood of the possible outcomes of different alternatives. The integration of this information

is made through some type of expectation, based calculus (cognitive activity) which enables us

to make a decision. In this theory, psychological processes and the decision maker’s emotional

state were ignored and not taken into account as inputs to the expectation based calculus.

Emotions as an information source

In “Risk as Feelings”, Loewenstein, Weber and Hsee [1] argue that these processes of decision

making include ‘anticipatory emotions’ and ‘anticipated emotions’: “anticipatory emotions are

immediate visceral reactions (fear, anxiety, dread) to risk and uncertainties”; “anticipated

emotions are typically not experienced in the immediate present but are expected to be

experienced in the future” (disappointment or regret). Both types of emotions serve as

additional source of information.

For example, research shows that happy decision-makers are reluctant to gamble. The fact that

a person is happy would make him or her decide against gambling, since he or she would not

want to undermine his or her happy feeling. This can be looked upon as "mood maintenance"

[2].

According to the information hypothesis, feelings during the decision process affects people's

choices, in cases where feelings are experienced as reactions to the imminent decision. If

feelings are attributed to an irrelevant source to the decision at hand, their impact is reduced or

eliminated.

Zajonc [3] argues that emotions are meant to help people take or avoid taking a stand, versus

cognitive calculus that helps people make a true/false decision.

Anticipated Pleasure

Mellers and McGraw (2001) [4] proposed that anticipated pleasure is an emotion that is

generated during the decision making process and is taken into account as an additional

information source. They argued that the decision maker estimates how he or she will feel

when he or she is right or wrong as a result of choosing one of the alternatives. These

estimated feelings are “averaged” and compared between the different alternatives. It seems

that this theory is the same as the expected utility theory (EU) but both can result in different

choices.

Implications to decision making processes

In a research from 2001, Isen suggests that tasks which are meaningful, interesting, or

important to the decision maker; and if he or she is in a good mood, the decision making

process will be more efficient and thorough. People will usually integrate material for decision

making and be less confused by a large set of variables, if the conditions are of positive affect.

This allows the decision makers to work faster and they will either finish the task at hand

quicker, or will turn attention to other important tasks. Positive affect generally leads people to

be gracious, generous, and kind to others; to be socially responsible and to take other’s

perspective better in interaction.

Emotional bias

An emotional bias is a distortion in cognition and decision making due to emotional factors.

That is, a person will be usually inclined

to believe something that has a positive emotional effect, that gives a pleasant feeling, even if

there is evidence to the contrary.

to be reluctant to accept hard facts that are unpleasant and gives mental suffering.

Those factors can be either individual and self-centered, or linked to interpersonal relationship

or to group influence.

The effects of emotional biases

Its effects can be similar to those of a cognitive bias, it can even be considered as a subcategory

of such biases. The specificity is that the cause lies in one's desires or fears, which divert the

attention of the person, more than in one's reasoning.

Neuroscience experiments have shown how emotions and cognition, which are present in

different areas of the human brain, interfere between each other in the decision making

process, resulting often on a primacy of emotions over reasoning [1]

This might explain some irrational and damaging reactions and moves that might take place

when those emotions are biased (in case of over-optimism or over-pessimism for example).

Greed and fear

Greed and fear are supposed, together with herd instinct, to be the three main emotional

motivators of stock markets and business behavior, and one of the cause of bull markets, bear

markets and business cycles.[citation needed]

From a market saying to an academic research topic

The phrase, traditionally used by traders and market commentators, has become a topic of

economic research about investor irrationalities (cognitive and emotional biases). Its effects on

market prices and returns contradict, or at least moderate, the efficient market hypothesis.

Here are two examples of approaches:

How those two alterning emotions work for traders, and how they can distort their decision

process, has been the subject of neuroeconomics studies (1). More generally, those researches

show some primacy of emotion over cognition in decision making.

According to Hersh Shefrin, one of the key researchers in Behavioral economics, the phrase

hope and fear, although less colloquially used, would describe better those alterning excessive

expectations by market players

Wishful thinking

Wishful thinking is the formation of beliefs and making decisions according to what might be

pleasing to imagine instead of by appealing to evidence or rationality.

Studies have consistently shown that holding all else equal, subjects will predict positive

outcomes to be more likely than negative outcomes. See positive outcome bias.

Prominent examples of wishful thinking include:

Economist Irving Fisher said that "stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high

plateau" a few weeks before Stock Market Crash of 1929, which was followed by the Great

Depression.

President John F. Kennedy believed that, if overpowered by Cuban forces, the CIA-backed rebels

could "escape destruction by melting into the countryside" in the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

As a logical fallacy

In addition to being a cognitive bias and a poor way of making decisions, wishful thinking is

commonly held to be a specific logical fallacy in an argument when it is assumed that because

we wish something to be true or false that it is actually true or false. This fallacy has the form "I

wish that P is true/false, therefore P is true/false."[1] Wishful thinking, if this were true, would

underlie appeals to emotion, and would also be a red herring.

Some atheists argue that much of theology, particularly arguments for the existence of God, is

based on wishful thinking because it takes the desired outcome (that a god or gods exist) and

tries to prove it on the basis of a premise through reasoning which can be analysed as

fallacious, but which may nevertheless be wished "true" in the mind of the believer. Some

theologians argue that it is actually atheism which is the product of wishful thinking, in that

atheists may not want to believe in any gods or may not want there to be any gods. Both of

these arguments would better be described as confirmation bias. Since one rarely, if ever, finds

an argument written or spoken as described above ("I wish it to be true, therefore it is true"),

the charge of "wishful thinking" itself can be a form of circumstantial ad hominem argument,

even a Bulverism.

Wishful thinking may cause blindness to unintended consequences.

Related fallacies are the Negative proof and Argument from ignorance fallacies ("It hasn't been proven

false, so it must be true." and vice versa). For instance, a believer in UFOs may accept that most UFO

photos are faked, but claim that the ones that haven't been debunked must be considered genuine.

Chapter 4

Risk

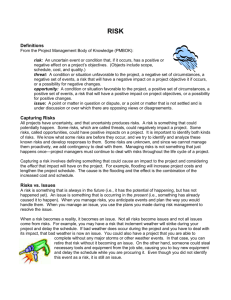

Risk is a concept that denotes the precise probability of specific eventualities. Technically, the notion of

risk is independent from the notion of value, and as such, eventualities may have both beneficial and

adverse consequences. However in general usage the convention is to focus only on potential negative

impact to some characteristic of value that may arise from a future event. Definitions of risk

There are many definitions of risk that vary by specific application and situational context. One is that

risk is an issue, which can be avoided or mitigated (wherein an issue is a potential problem that has to

be fixed now.) Risk is described both qualitatively and quantitatively. In some texts risk is described as a

situation which would lead to negative consequences.

Qualitatively, risk is proportional to both the expected losses which may be caused by an event and to

the probability of this event. Greater loss and greater event likelihood result in a greater overall risk.

Frequently in the subject matter literature, risk is defined in pseudo-formal forms where the

components of the definition are vague and ill-defined, for example, risk is considered as an indicator of

threat, or depends on threats, vulnerability, impact and uncertainty.[citation needed]

In engineering, the definition risk often simply is:

\text{Risk} = (\text{probability of an accident}) \times (\text{losses per accident}).\,

Or in more general terms:

\text{Risk} = (\text{probability of risk occurring}) \times (\text{impact of risk occuring}).\,

There are more sophisticated definitions, however. Measuring engineering risk is often difficult,

especially in potentially dangerous industries such as nuclear energy. Often, the probability of a negative

event is estimated by using the frequency of past similar events or by event-tree methods, but

probabilities for rare failures may be difficult to estimate if an event tree cannot be formulated.

Methods to calculate the cost of the loss of human life vary depending on the purpose of the

calculation. Specific methods include what people are willing to pay to insure against death,[1] and

radiological release (e.g., GBq of radio-iodine).[citation needed] There are many formal methods used to

assess or to "measure" risk, considered as one of the critical indicators important for human decision

making.

Financial risk is often defined as the unexpected variability or volatility of returns and thus includes both

potential worse-than-expected as well as better-than-expected returns. References to negative risk

below should be read as applying to positive impacts or opportunity (e.g., for "loss" read "loss or gain")

unless the context precludes.

In statistics, risk is often mapped to the probability of some event which is seen as undesirable. Usually,

the probability of that event and some assessment of its expected harm must be combined into a

believable scenario (an outcome), which combines the set of risk, regret and reward probabilities into an

expected value for that outcome. (See also Expected utility.)

Thus, in statistical decision theory, the risk function of an estimator δ(x) for a parameter θ, calculated

from some observables x, is defined as the expectation value of the loss function L,

R(\theta,\delta(x)) = \int L(\theta,\delta(x)) f(x|\theta)\,dx

In information security[citation needed], a risk is defined as a function of three variables:

1. the probability that there is a threat

2. the probability that there are any vulnerabilities

3. the potential impact.

If any of these variables approaches zero, the overall risk approaches zero.

The management of actuarial risk is called risk management.

Historical background

Scenario analysis matured during Cold War confrontations between major powers, notably the U.S. and

the USSR. It became widespread in insurance circles in the 1970s when major oil tanker disasters forced

a more comprehensive foresight.[citation needed] The scientific approach to risk entered finance in the

1980s when financial derivatives proliferated. It reached general professions in the 1990s when the

power of personal computing allowed for widespread data collection and numbers crunching.

Governments are apparently only now learning to use sophisticated risk methods, most obviously to set

standards for environmental regulation, e.g. "pathway analysis" as practiced by the United States

Environmental Protection Agency.

Risk versus uncertainty

In his seminal work Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, Frank Knight (1921) established the distinction

between risk and uncertainty.

“

... Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from

which it has never been properly separated. The term "risk," as loosely used in everyday speech and in

economic discussion, really covers two things which, functionally at least, in their causal relations to the

phenomena of economic organization, are categorically different. ... The essential fact is that "risk"

means in some cases a quantity susceptible of measurement, while at other times it is something

distinctly not of this character; and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the

phenomenon depending on which of the two is really present and operating. ... It will appear that a

measurable uncertainty, or "risk" proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an

unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all. We ... accordingly restrict the term

"uncertainty" to cases of the non-quantitive type.

”

A solution to this ambiguity is proposed in "How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles

in Business" by Doug Hubbard:[2]

Uncertainty: The lack of complete certainty, that is, the existence of more than one possibility. The

"true" outcome/state/result/value is not known.

Measurement of uncertainty: A set of probabilities assigned to a set of possibilities. Example:

"There is a 60% chance this market will double in five years"

Risk: A state of uncertainty where some of the possibilities involve a loss, catastrophe, or other

undesirable outcome.

Measurement of risk: A set of possibilities each with quantified probabilities and quantified losses.

Example: "There is a 40% chance the proposed oil well will be dry with a loss of $12 million in

exploratory drilling costs".

In this sense, Hubbard uses the terms so that one may have uncertainty without risk but not risk without

uncertainty. We can be uncertain about the winner of a contest, but unless we have some personal

stake in it, we have no risk. If we bet money on the outcome of the contest, then we have a risk. In both

cases there are more than one outcome. The measure of uncertainty refers only to the probabilities

assigned to outcomes, while the measure of risk requires both probabilities for outcomes and losses

quantified for outcomes.

Insurance and health risk

Insurance is a risk-reducing investment in which the buyer pays a small fixed amount to be protected

from a potential large loss. Gambling is a risk-increasing investment, wherein money on hand is risked

for a possible large return, but with the possibility of losing it all. Purchasing a lottery ticket is a very

risky investment with a high chance of no return and a small chance of a very high return. In contrast,

putting money in a bank at a defined rate of interest is a risk-averse action that gives a guaranteed

return of a small gain and precludes other investments with possibly higher gain.

Risks in personal health may be reduced by primary prevention actions that decrease early causes of

illness or by secondary prevention actions after a person has clearly measured clinical signs or symptoms

recognized as risk factors. Tertiary prevention (medical) reduces the negative impact of an already

established disease by restoring function and reducing disease-related complications. Ethical medical

practice requires careful discussion of risk factors with individual patients to obtain informed consent for

secondary and tertiary prevention efforts, whereas public health efforts in primary prevention require

education of the entire population at risk. In each case, careful communication about risk factors, likely

outcomes and certainty must distinguish between causal events that must be decreased and associated

events that may be merely consequences rather than causes.

Economic risk

Insight

The central insight in the methodology for incorporating economic risks arise from the realization of the

fact that however manifold and diverse might be the causes, or factors, of risks around a specific project

or business (for instance, the hike in the price for raw materials, the lapsing of deadlines for construction

of a new operating facility, disruptions in a production process, emergence of a serious competitor on

the market, the loss of key personnel, the change of a political regime, natural contingencies, etc.), all of

these are ultimately manifested under only two guises. According to CCF Conception the economic risk

consists in that: "Actual positive conventional cash flows (income, inflows) turn out to be less than

expected AND / OR Actual negative conventional cash flows (expenditures, outflows) turn out to be

larger than expected (in absolute terms)".

Such lucid and unambiguous conceptual treatment of such a complex and multi-faceted notion as the

economic risk emphasizes the very core of the question. The "economic risk is not an abstract

‘uncertainty’ or ‘possibility of failure’ or changeableness (variability) of the outcome… The economic risk

– is a monetary amount which might be under-collected and/or over-paid." Just as in music, one must

use musical notes and staves—not alphabet letters or colors—to render a melody, in describing

economic risk, we must ultimately operate with monetary units and not with the percentages of

discount rates, magnitudes of volatility or anything else. (See [1].)

In business

Means of assessing risk vary widely between professions. Indeed, they may define these professions; for

example, a doctor manages medical risk, while a civil engineer manages risk of structural failure. A

professional code of ethics is usually focused on risk assessment and mitigation (by the professional on

behalf of client, public, society or life in general).

In the workplace, incidental and inherent risks exist. Incidental risks are those which occur naturally in

the business but are not part of the core of the business. Inherent risks have a negative effect on the

operating profit of the business.

Criticism

Criticism has been leveled at the amoral ("rational") application of quantitative risk assessment.[citation

needed]

Risk-sensitive industries

Some industries manage risk in a highly quantified and numerate way. These include the nuclear power

and aircraft industries, where the possible failure of a complex series of engineered systems could result

in highly undesirable outcomes. The usual measure of risk for a class of events is then:

R = probability of the event × C

The total risk is then the sum of the individual class-risks.

In the nuclear industry, consequence is often measured in terms of off-site radiological release, and this

is often banded into five or six decade-wide bands.

The risks are evaluated using fault tree/event tree techniques (see safety engineering). Where these

risks are low, they are normally considered to be "Broadly Acceptable". A higher level of risk (typically up

to 10 to 100 times what is considered Broadly Acceptable) has to be justified against the costs of

reducing it further and the possible benefits that make it tolerable—these risks are described as

"Tolerable if ALARP". Risks beyond this level are classified as "Intolerable".

The level of risk deemed Broadly Acceptable has been considered by regulatory bodies in various

countries—an early attempt by UK government regulator and academic F. R. Farmer used the example

of hill-walking and similar activities which have definable risks that people appear to find acceptable.

This resulted in the so-called Farmer Curve of acceptable probability of an event versus its consequence.

The technique as a whole is usually referred to as Probabilistic Risk Assessment (PRA) (or Probabilistic

Safety Assessment, PSA). See WASH-1400 for an example of this approach.

In finance

In finance, risk is the probability that an investment's actual return will be different than expected. This

includes the possibility of losing some or all of the original investment. It is usually measured by

calculating the standard deviation of the historical returns or average returns of a specific

investment.[citation needed]

In finance, risk has no one definition, but some theorists, notably Ron Dembo, have defined quite

general methods to assess risk as an expected after-the-fact level of regret. Such methods have been

uniquely successful in limiting interest rate risk in financial markets. Financial markets are considered to

be a proving ground for general methods of risk assessment.

However, these methods are also hard to understand. The mathematical difficulties interfere with other

social goods such as disclosure, valuation and transparency. In particular, it is often difficult to tell if such

financial instruments are "hedging" (purchasing/selling a financial instrument specifically to reduce or

cancel out the risk in another investment) or "gambling" (increasing measurable risk and exposing the

investor to catastrophic loss in pursuit of very high windfalls that increase expected value).

As regret measures rarely reflect actual human risk-aversion, it is difficult to determine if the outcomes

of such transactions will be satisfactory. Risk seeking describes an individual whose utility function's

second derivative is positive. Such an individual would willingly (actually pay a premium to) assume all

risk in the economy and is hence not likely to exist.

In financial markets, one may need to measure credit risk, information timing and source risk,

probability model risk, and legal risk if there are regulatory or civil actions taken as a result of some

"investor's regret".

"A fundamental idea in finance is the relationship between risk and return. The greater the amount of

risk that an investor is willing to take on, the greater the potential return. The reason for this is that

investors need to be compensated for taking on additional risk."

"For example, a US Treasury bond is considered to be one of the safest investments and, when

compared to a corporate bond, provides a lower rate of return. The reason for this is that a corporation

is much more likely to go bankrupt than the U.S. government. Because the risk of investing in a

corporate bond is higher, investors are offered a higher rate of return."

In public works

In a peer reviewed study of risk in public works projects located in twenty nations on five continents,

Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl (2002, 2005) documented high risks for such ventures for both costs [2] and

demand [3]. Actual costs of projects were typically higher than estimated costs; cost overruns of 50%

were common, overruns above 100% not uncommon. Actual demand was often lower than estimated;

demand shortfalls of 25% were common, of 50% not uncommon.

Due to such cost and demand risks, cost-benefit analyses of public works projects have proved to be

highly uncertain.

The main causes of cost and demand risks were found to be optimism bias and strategic

misrepresentation. Measures identified to mitigate this type of risk are better governance through

incentive alignment and the use of reference class forecasting. [4]

In human services

Huge ethical and political issues arise when human beings themselves are seen or treated as 'risks', or

when the risk decision making of people who use human services might have an impact on that service.

The experience of many people who rely on human services for support is that 'risk' is often used as a

reason to prevent them from gaining further independence or fully accessing the community, and that

these services are often unnecessarily risk averse.[3]

Regret

In decision theory, regret (and anticipation of regret) can play a significant part in decision-making,

distinct from risk aversion (preferring the status quo in case one becomes worse off).

Framing

Framing (Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman, 1981. "The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of

Choice.") is a fundamental problem with all forms of risk assessment. In particular, because of bounded

rationality (our brains get overloaded, so we take mental shortcuts), the risk of extreme events is

discounted because the probability is too low to evaluate intuitively. As an example, one of the leading

causes of death is road accidents caused by drunk driving—partly because any given driver frames the

problem by largely or totally ignoring the risk of a serious or fatal accident.

For instance, an extremely disturbing event (an attack by hijacking, or moral hazards) may be ignored in

analysis despite the fact it has occurred and has a nonzero probability. Or, an event that everyone

agrees is inevitable may be ruled out of analysis due to greed or an unwillingness to admit that it is

believed to be inevitable. These human tendencies to error and wishful thinking often affect even the

most rigorous applications of the scientific method and are a major concern of the philosophy of

science.

All decision-making under uncertainty must consider cognitive bias, cultural bias, and notational bias: No

group of people assessing risk is immune to "groupthink": acceptance of obviously wrong answers

simply because it is socially painful to disagree, where there are conflicts of interest. One effective way

to solve framing problems in risk assessment or measurement (although some argue that risk cannot be

measured, only assessed) is to raise others' fears or personal ideals by way of completeness.

Fear as intuitive risk assessment

For the time being, people rely on their fear and hesitation to keep them out of the most profoundly

unknown circumstances.

In The Gift of Fear, Gavin de Becker argues that "True fear is a gift. It is a survival signal that sounds only

in the presence of danger. Yet unwarranted fear has assumed a power over us that it holds over no

other creature on Earth. It need not be this way."

Risk could be said to be the way we collectively measure and share this "true fear"—a fusion of rational

doubt, irrational fear, and a set of unquantified biases from our own experience.

The field of behavioral finance focuses on human risk-aversion, asymmetric regret, and other ways that

human financial behavior varies from what analysts call "rational". Risk in that case is the degree of

uncertainty associated with a return on an asset.

Recognizing and respecting the irrational influences on human decision making may do much to reduce

disasters caused by naive risk assessments that pretend to rationality but in fact merely fuse many

shared biases together.

Root causes of risk

Optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation have been found to be root causes of risk.[citation

needed]

Risk assessment and management

Because planned actions are subject to large cost and benefit risks, proper risk assessment and risk

management for such actions are crucial to making them successful (Flyvbjerg 2006).

Since Risk assessment and management is essential in security management, both are tightly related.

Security assessment methodologies like BEATO or CRAMM contain risk assessment modules as an

important part of the first steps of the methodology. On the other hand, Risk Assessment

methodologies, like Mehari evolved to become Security Assessment methodologies. A ISO standard on

risk management (Principles and guidelines on implementation) is currently being draft under code

ISO/DIS 31000. Target publication date 30 May 2009.

Risk in auditing

The audit risk model expresses the risk of an auditor providing an inappropriate opinion of a commercial

entity's financial statements. It can be analytically expressed as:

AR = IR x CR x DR

Where AR is audit risk, IR is inherent risk, CR is control risk and DR is detection risk.

Categories of risks

* Political: Change of government, cross cutting policy decisions (e.g., the Euro).

* Regulatory: Change of policy by state, national or multinational regulatory bodies

* Market: Fundamental change in supply and demand functions or global prices for commodities

* Professional: Associated with the nature of each profession.

* Economic: Ability to attract and retain staff in the labour market; exchange rates affect costs of

international transactions; effect of global economy on UK economy.

* Socio-cultural: Demographic change affects demand for services; stakeholder expectations change.

* Health and Safety: Buildings, vehicles, equipment, fire, noise, vibration, asbestos, chemical and

biological hazards, food safety, traffic management, stress, lone working, etc.

* Technological: Obsolescence of current systems; cost of procuring best technology available,

opportunity arising from technological development.

* Contractual: Associated with the failure of contractors to deliver devices or products to the agreed

cost and specification.

* Environmental: Buildings need to comply with changing standards; disposal of rubbish and surplus

equipment needs to comply with changing standards.

* Physical: Theft, vandalism, arson, building related risks, Storm, flood, other related weather, damage

to vehicles, mobile plant and equipment.

* Operational: Relating to existing operations – both current delivery and building and maintaining.

Chapter 5

Risk

management

Risk management is a structured approach to managing uncertainty related to a threat, a sequence of

human activities including: risk assessment, strategies development to manage it, and mitigation of risk

using managerial resources.

The strategies include transferring the risk to another party, avoiding the risk, reducing the negative

effect of the risk, and accepting some or all of the consequences of a particular risk.

Some traditional risk managements are focused on risks stemming from physical or legal causes (e.g.

natural disasters or fires, accidents, ergonomics, death and lawsuits). Financial risk management, on the

other hand, focuses on risks that can be managed using traded financial instruments.

The objective of risk management is to reduce different risks related to a preselected domain to the

level accepted by society. It may refer to numerous types of threats caused by environment, technology,

humans, organizations and politics. On the other hand it involves all means available for humans, or in

particular, for a risk management entity (person, staff, organization). Some explanations

In ideal risk management, a prioritization process is followed whereby the risks with the greatest loss

and the greatest probability of occurring are handled first, and risks with lower probability of occurrence

and lower loss are handled in descending order. In practice the process can be very difficult, and

balancing between risks with a high probability of occurrence but lower loss versus a risk with high loss

but lower probability of occurrence can often be mishandled.

Intangible risk management identifies a new type of risk - a risk that has a 100% probability of occurring

but is ignored by the organization due to a lack of identification ability. For example, when deficient

knowledge is applied to a situation, a knowledge risk materialises. Relationship risk appears when

ineffective collaboration occurs. Process-engagement risk may be an issue when ineffective operational

procedures are applied. These risks directly reduce the productivity of knowledge workers, decrease

cost effectiveness, profitability, service, quality, reputation, brand value, and earnings quality. Intangible

risk management allows risk management to create immediate value from the identification and

reduction of risks that reduce productivity.

Risk management also faces difficulties allocating resources. This is the idea of opportunity cost.

Resources spent on risk management could have been spent on more profitable activities. Again, ideal

risk management minimizes spending while maximizing the reduction of the negative effects of risks.

Steps in the risk management process

Establish the context

Establishing the context involves

1. Identification of risk in a selected domain of interest

2. Planning the remainder of the process.

3. Mapping out the following:

* the social scope of risk management

* the identity and objectives of stakeholders

* the basis upon which risks will be evaluated, constraints.

4. Defining a framework for the activity and an agenda for identification.

5. Developing an analysis of risks involved in the process.

6. Mitigation of risks using available technological, human and organizational resources.

Identification

After establishing the context, the next step in the process of managing risk is to identify potential risks.

Risks are about events that, when triggered, cause problems. Hence, risk identification can start with the

source of problems, or with the problem itself.

* Source analysis Risk sources may be internal or external to the system that is the target of risk

management. Examples of risk sources are: stakeholders of a project, employees of a company or the

weather over an airport.

* Problem analysis Risks are related to identified threats. For example: the threat of losing money, the

threat of abuse of privacy information or the threat of accidents and casualties. The threats may exist

with various entities, most important with shareholders, customers and legislative bodies such as the

government.

When either source or problem is known, the events that a source may trigger or the events that can

lead to a problem can be investigated. For example: stakeholders withdrawing during a project may

endanger funding of the project; privacy information may be stolen by employees even within a closed

network; lightning striking a Boeing 747 during takeoff may make all people onboard immediate

casualties.

The chosen method of identifying risks may depend on culture, industry practice and compliance. The

identification methods are formed by templates or the development of templates for identifying source,

problem or event. Common risk identification methods are:

* Objectives-based risk identification Organizations and project teams have objectives. Any event that

may endanger achieving an objective partly or completely is identified as risk.

* Scenario-based risk identification In scenario analysis different scenarios are created. The scenarios

may be the alternative ways to achieve an objective, or an analysis of the interaction of forces in, for

example, a market or battle. Any event that triggers an undesired scenario alternative is identified as

risk - see Futures Studies for methodology used by Futurists.

* Taxonomy-based risk identification The taxonomy in taxonomy-based risk identification is a

breakdown of possible risk sources. Based on the taxonomy and knowledge of best practices, a

questionnaire is compiled. The answers to the questions reveal risks. Taxonomy-based risk identification

in software industry can be found in CMU/SEI-93-TR-6.

* Common-risk Checking In several industries lists with known risks are available. Each risk in the list

can be checked for application to a particular situation. An example of known risks in the software

industry is the Common Vulnerability and Exposures list found at http://cve.mitre.org.

* Risk Charting This method combines the above approaches by listing Resources at risk, Threats to

those resources Modifying Factors which may increase or decrease the risk and Consequences it is

wished to avoid. Creating a matrix under these headings enables a variety of approaches. One can begin

with resources and consider the threats they are exposed to and the consequences of each.

Alternatively one can start with the threats and examine which resources they would affect, or one can

begin with the consequences and determine which combination of threats and resources would be

involved to bring them about.

Assessment

Once risks have been identified, they must then be assessed as to their potential severity of loss and to

the probability of occurrence. These quantities can be either simple to measure, in the case of the value

of a lost building, or impossible to know for sure in the case of the probability of an unlikely event

occurring. Therefore, in the assessment process it is critical to make the best educated guesses possible

in order to properly prioritize the implementation of the risk management plan.

The fundamental difficulty in risk assessment is determining the rate of occurrence since statistical

information is not available on all kinds of past incidents. Furthermore, evaluating the severity of the

consequences (impact) is often quite difficult for immaterial assets. Asset valuation is another question

that needs to be addressed. Thus, best educated opinions and available statistics are the primary

sources of information. Nevertheless, risk assessment should produce such information for the

management of the organization that the primary risks are easy to understand and that the risk

management decisions may be prioritized. Thus, there have been several theories and attempts to

quantify risks. Numerous different risk formulae exist, but perhaps the most widely accepted formula

for risk quantification is:

Rate of occurrence multiplied by the impact of the event equals risk

Later research has shown that the financial benefits of risk management are less dependent on the

formula used but are more dependent on the frequency and how risk assessment is performed.

In business it is imperative to be able to present the findings of risk assessments in financial terms.

Robert Courtney Jr. (IBM, 1970) proposed a formula for presenting risks in financial terms. The Courtney

formula was accepted as the official risk analysis method for the US governmental agencies. The formula

proposes calculation of ALE (annualised loss expectancy) and compares the expected loss value to the

security control implementation costs (cost-benefit analysis).

Potential risk treatments

Once risks have been identified and assessed, all techniques to manage the risk fall into one or more of

these four major categories:[1]

* Avoidance (eliminate)

* Reduction (mitigate)

* Transference (outsource or insure)

* Retention (accept and budget)

Ideal use of these strategies may not be possible. Some of them may involve trade-offs that are not

acceptable to the organization or person making the risk management decisions. Another source, from

the US Department of Defense, Defense Acquisition University, calls these categories ACAT, for Avoid,

Control, Accept, or Transfer. This use of the ACAT acronym is reminiscent of another ACAT (for

Acquisition Category) used in US Defense industry procurements, in which Risk Management figures

prominently in decision making and planning.

Risk avoidance

Includes not performing an activity that could carry risk. An example would be not buying a property or

business in order to not take on the liability that comes with it. Another would be not flying in order to

not take the risk that the airplane were to be hijacked. Avoidance may seem the answer to all risks, but

avoiding risks also means losing out on the potential gain that accepting (retaining) the risk may have

allowed. Not entering a business to avoid the risk of loss also avoids the possibility of earning profits.

Risk reduction

Involves methods that reduce the severity of the loss or the likelihood of the loss from occurring.

Examples include sprinklers designed to put out a fire to reduce the risk of loss by fire. This method may

cause a greater loss by water damage and therefore may not be suitable. Halon fire suppression systems

may mitigate that risk, but the cost may be prohibitive as a strategy.

Modern software development methodologies reduce risk by developing and delivering software

incrementally. Early methodologies suffered from the fact that they only delivered software in the final

phase of development; any problems encountered in earlier phases meant costly rework and often

jeopardized the whole project. By developing in iterations, software projects can limit effort wasted to a

single iteration.

Outsourcing could be an example of risk reduction if the outsourcer can demonstrate higher capability

at managing or reducing risks. [2] In this case companies outsource only some of their departmental

needs. For example, a company may outsource only its software development, the manufacturing of

hard goods, or customer support needs to another company, while handling the business management

itself. This way, the company can concentrate more on business development without having to worry

as much about the manufacturing process, managing the development team, or finding a physical

location for a call center.

Risk retention

Involves accepting the loss when it occurs. True self insurance falls in this category. Risk retention is a

viable strategy for small risks where the cost of insuring against the risk would be greater over time than

the total losses sustained. All risks that are not avoided or transferred are retained by default. This

includes risks that are so large or catastrophic that they either cannot be insured against or the

premiums would be infeasible. War is an example since most property and risks are not insured against

war, so the loss attributed by war is retained by the insured. Also any amounts of potential loss (risk)

over the amount insured is retained risk. This may also be acceptable if the chance of a very large loss is

small or if the cost to insure for greater coverage amounts is so great it would hinder the goals of the

organization too much.

Risk Transference

Many sectors have for a long time regarded insurance as a transfer of risk. This is not correct. Insurance

is a post event compensatory mechanism. That is, even if an insurance policy has been effected this

does not mean that the risk has been transferred. For example, a personal injuries insurance policy does

not transfer the risk of a car accident to the insurance company. The risk still lies with the policy holder

namely the person who has been in the accident. The insurance policy simply provides that if an

accident (the event) occurs involving the policy holder then some compensation may be payable to the

policy holder that is commensurate to the suffering/damage.

{the rest needs to be substantially altered] Means causing another party to accept the risk, typically by

contract or by hedging. Insurance is one type of risk transfer that uses contracts. Other times it may

involve contract language that transfers a risk to another party without the payment of an insurance

premium. Liability among construction or other contractors is very often transferred this way. On the

other hand, taking offsetting positions in derivatives is typically how firms use hedging to financially

manage risk.

Some ways of managing risk fall into multiple categories. Risk retention pools are technically retaining

the risk for the group, but spreading it over the whole group involves transfer among individual

members of the group. This is different from traditional insurance, in that no premium is exchanged

between members of the group up front, but instead losses are assessed to all members of the group.

Create a risk management plan

Select appropriate controls or countermeasures to measure each risk. Risk mitigation needs to be

approved by the appropriate level of management. For example, a risk concerning the image of the

organization should have top management decision behind it whereas IT management would have the

authority to decide on computer virus risks.

The risk management plan should propose applicable and effective security controls for managing the

risks. For example, an observed high risk of computer viruses could be mitigated by acquiring and

implementing antivirus software. A good risk management plan should contain a schedule for control

implementation and responsible persons for those actions.

According to ISO/IEC 27001, the stage immediately after completion of the Risk Assessment phase

consists of preparing a Risk Treatment Plan, which should document the decisions about how each of

the identified risks should be handled. Mitigation of risks often means selection of Security Controls,

which should be documented in a Statement of Applicability, which identifies which particular control

objectives and controls from the standard have been selected, and why.

Implementation

Follow all of the planned methods for mitigating the effect of the risks. Purchase insurance policies for

the risks that have been decided to be transferred to an insurer, avoid all risks that can be avoided

without sacrificing the entity's goals, reduce others, and retain the rest.

Review and evaluation of the plan

Initial risk management plans will never be perfect. Practice, experience, and actual loss results will

necessitate changes in the plan and contribute information to allow possible different decisions to be

made in dealing with the risks being faced.

Risk analysis results and management plans should be updated periodically. There are two primary

reasons for this:

1. to evaluate whether the previously selected security controls are still applicable and effective, and

2. to evaluate the possible risk level changes in the business environment. For example, information

risks are a good example of rapidly changing business environment.

Limitations

If risks are improperly assessed and prioritized, time can be wasted in dealing with risk of losses that are

not likely to occur. Spending too much time assessing and managing unlikely risks can divert resources

that could be used more profitably. Unlikely events do occur but if the risk is unlikely enough to occur it

may be better to simply retain the risk and deal with the result if the loss does in fact occur.

Prioritizing too highly the risk management processes could keep an organization from ever completing

a project or even getting started. This is especially true if other work is suspended until the risk

management process is considered complete.

It is also important to keep in mind the distinction between risk and uncertainty. Risk can be measured

by impacts x probability.

Areas of risk management

As applied to corporate finance, risk management is the technique for measuring, monitoring and

controlling the financial or operational risk on a firm's balance sheet. See value at risk.

The Basel II framework breaks risks into market risk (price risk), credit risk and operational risk and also

specifies methods for calculating capital requirements for each of these components.

Enterprise risk management

In enterprise risk management, a risk is defined as a possible event or circumstance that can have

negative influences on the enterprise in question. Its impact can be on the very existence, the resources

(human and capital), the products and services, or the customers of the enterprise, as well as external

impacts on society, markets, or the environment. In a financial institution, enterprise risk management

is normally thought of as the combination of credit risk, interest rate risk or asset liability management,

market risk, and operational risk.

In the more general case, every probable risk can have a pre-formulated plan to deal with its possible

consequences (to ensure contingency if the risk becomes a liability).

From the information above and the average cost per employee over time, or cost accrual ratio, a

project manager can estimate:

* the cost associated with the risk if it arises, estimated by multiplying employee costs per unit time

by the estimated time lost (cost impact, C where C = cost accrual ratio * S).

* the probable increase in time associated with a risk (schedule variance due to risk, Rs where Rs = P *

S):

o Sorting on this value puts the highest risks to the schedule first. This is intended to cause the

greatest risks to the project to be attempted first so that risk is minimized as quickly as possible.

o This is slightly misleading as schedule variances with a large P and small S and vice versa are not

equivalent. (The risk of the RMS Titanic sinking vs. the passengers' meals being served at slightly the

wrong time).

* the probable increase in cost associated with a risk (cost variance due to risk, Rc where Rc = P*C =

P*CAR*S = P*S*CAR)

o sorting on this value puts the highest risks to the budget first.

o see concerns about schedule variance as this is a function of it, as illustrated in the equation

above.

Risk in a project or process can be due either to Special Cause Variation or Common Cause Variation and

requires appropriate treatment. That is to re-iterate the concern about extremal cases not being

equivalent in the list immediately above.

Risk management activities as applied to project management

In project management, risk management includes the following activities:

* Planning how risk management will be held in the particular project. Plan should include risk

management tasks, responsibilities, activities and budget.

* Assigning a risk officer - a team member other than a project manager who is responsible for

foreseeing potential project problems. Typical characteristic of risk officer is a healthy skepticism.

* Maintaining live project risk database. Each risk should have the following attributes: opening date,

title, short description, probability and importance. Optionally a risk may have an assigned person

responsible for its resolution and a date by which the risk must be resolved.

* Creating anonymous risk reporting channel. Each team member should have possibility to report risk

that he foresees in the project.

* Preparing mitigation plans for risks that are chosen to be mitigated. The purpose of the mitigation

plan is to describe how this particular risk will be handled – what, when, by who and how will it be done

to avoid it or minimize consequences if it becomes a liability.

* Summarizing planned and faced risks, effectiveness of mitigation activities, and effort spent for the

risk management.

Risk management and business continuity

Risk management is simply a practice of systematically selecting cost effective approaches for

minimising the effect of threat realization to the organization. All risks can never be fully avoided or

mitigated simply because of financial and practical limitations. Therefore all organizations have to

accept some level of residual risks.

Whereas risk management tends to be preemptive, business continuity planning (BCP) was invented to

deal with the consequences of realised residual risks. The necessity to have BCP in place arises because

even very unlikely events will occur if given enough time. Risk management and BCP are often

mistakenly seen as rivals or overlapping practices. In fact these processes are so tightly tied together

that such separation seems artificial. For example, the risk management process creates important

inputs for the BCP (assets, impact assessments, cost estimates etc). Risk management also proposes

applicable controls for the observed risks. Therefore, risk management covers several areas that are

vital for the BCP process. However, the BCP process goes beyond risk management's preemptive

approach and moves on from the assumption that the disaster will realize at some point.

Chapter 6

Responsible

decision

making

People have different ways of making decisions. Inactive decision making is delaying a decision in the

hope that the situation will resolve itself. Reactive decision making is allowing the views and opinions of

others to determine your decision. Proactive decision making, on the other hand, is looking at a decision

that must be made, considering the options, choosing a plan of action, and taking responsibility for the

outcome. Proactive decision making gives a person a greater degree of control over the problem