031 - Columbia University

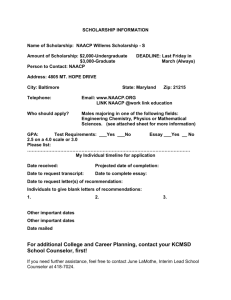

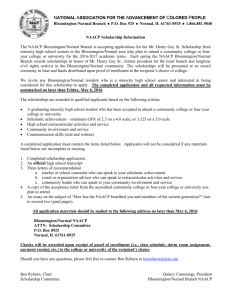

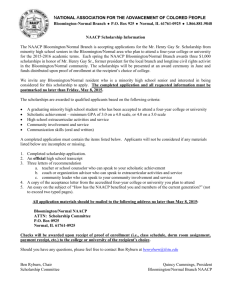

advertisement