VI - paul riker

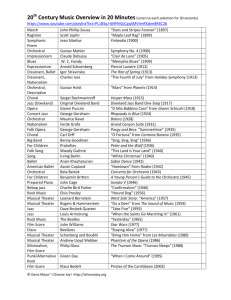

advertisement