Carved in Stone Reading

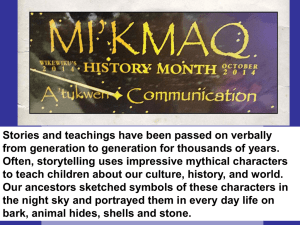

advertisement

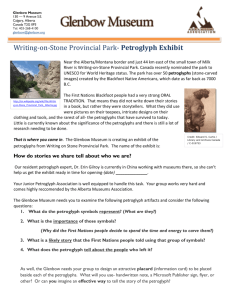

1 “Carved In Stone” Go To: http://museum.gov.ns.ca/imagesns/petroglyphs/ To see photographs of the petroglyphs documented by George Creed. The people of the Mi'kmaw First Nation have lived in what is now Nova Scotia and the Maritimes for thousands of years. They expressed their culture and world view in stories and traditions. We are able to glimpse aspects of Mi'kmaw traditions and culture through these stories and through the art they have created. The Mi'kmaq created enduring art. Some of this art has been carved into the rock of the province. These rock pictures, or petroglyphs, record their lives and the things they saw around them. Many petroglyphs can be found along the rocky shores of the lakes and rivers of Kejimkujik National Park, the Medway River and McGowan Lake, in southwest Nova Scotia. Petroglyphs have also been created at several other locations around the province. The smooth, fine-grained slates found in the Kejimkujik area make an excellent surface for recording images. The lines were cut, scratched, or pecked using stone or metal tools. The Mi'kmaq recorded images of people, animals, hunting, fishing, and the decorative motifs women sewed or painted on clothing. With the arrival of the Europeans, the lives of the Mi'kmaq changed in new ways. Evidence of this change includes images of sailing ships, men hunting with muskets, soldiers, Christian altars and churches, and small items like coins and jack-knives. George Creed, the postmaster at South Rawdon in central Nova Scotia, made a series of tracings of the Mi'kmaw petroglyphs at Kejumkujik and McGowan Lake in 1887 and 1888. The bulk of Creed's tracings are presented here.It is impossible to accurately date most of the petroglyphs. Images of sailing ships, hunters with guns and European-style dwellings are clearly more recent. A few petroglyphs appear to have the year of their creation carved into the rock next to them, either from the 1800s or the 1900s. 2 Creed's tracings form the earliest attempt to document systematically the rock art in the province and are an important record of this culture. Constantly exposed to weather, many petroglyphs have become worn over time. In numerous cases, vandals have defaced the images. In some cases, Creed's tracings are now the only record that the image ever existed. At McGowan Lake, the petroglyphs have been underwater since the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the 1940's, except for a short period in 1983 when McGowan Lake was drained for repairs to the dam. At that time, archaeologist Brian Leigh Molyneaux was able to photograph the petroglyphs and make tracings, adding to the record made by Creed. The Creed tracings, as well as the photographs and tracings done by Molyneaux, are the only access we have to these petroglyphs. The petroglyphs at McGowan Lake have been protected from vandalism and weather by the water covering them and have been preserved much better than the ones at Kejimkujik. The long heritage of Mi'kmaw art continues today. Mi'kmaw artist Alan Syliboy, for example, blends modern themes and traditional petroglyph images to create a fusion of ancient and modern, expressing his pride and understanding of Mi'kmaw heritage. It is very difficult to accurately record petroglyphs. The shallow cuts and lines that make up the image - in the quartzite and slate stone favoured by the artists - are often eroded by years of water, ice and weather wearing the edges down and making the images less distinct. Most recordings have been done with either tracing the petroglyphs onto paper or other materials, or by taking photographs. Often some technique was used to prepare the petroglyphs to make the lines more distinct before recording. Tracings have the advantage that they are exactly the same size as the petroglyphs. Photographs of petroglyphs can be misleading if a scale is not included in the photo so that the size can be accurately shown. Casting, the third method, is the most accurate way to record rock carvings. Tracing: George Creed used a tracing technique. He examined the rock faces, went over those outlines he thought significant with blue aniline pencil, then pressed dampened paper over the tracing. The moisture in the paper transferred the pencil dye to the paper. This technique creates an image on the back of the paper that is a mirror image of the original, thus all of Creed's tracings are reversed when compared to the original carving. All of the images of Creed's tracings presented in this gallery have been reversed to represent the image as it existed in the rock. 3 Modern tracings are typically done on a transparent material such as mylar. The mylar sheet is placed over the petroglyph and the lines are traced with an ink pen, creating a correct image tracing of the petroglyph. Ruth Holmes Whitehead, Ethnologist at the Nova Scotia Museum, made this tracing of an early petroglyph in Bedford, NS, that was possibly cut with stone tools. Photography: Arthur and Olive Kelsall of Annapolis Royal, NS, photographed many of the petroglyphs in Kejimkujik National Park between 1946 and 1955. They created the first photographic record of Mi'kmaw rock art. The Kelsalls traced the lines in the rock with white ink to enhance the contrast with the darker rock, creating a stark but clear image. More recently Parks Canada and the Nova Scotia Museum have catalogued and photographed the petroglyphs within Kejimkujik National Park and at McGowan Lake, NS. For these photographs the petroglyphs were first painted in with white ink or watered-down poster paint. Carefully controlled lighting is used to get the best results. The light is aimed directly across the image, bringing up the shadows of the cut lines, rather than aiming a light from above. It enables the recorder to see the petroglyphs more clearly. To avoid interference from sunlight, much of this painting is done at night, then the images are photographed during the day, using natural light. Casting: Casting petroglyphs creates a very accurate copy that records the size and texture of the original. Casting is usually done with latex. The latex moulds can then be electroplated with copper to create a metal cast. Such copper casts are super-accurate and preserve a permanent record of the image. The Parks Canada has made moulds made of many petroglyph sites at Kejimkujik. George Creed grouped his petroglyph tracings into broad categories depending on the subjec: ships, people, canoes, animals, etc. In doing this he broke up groupings and made separate 4 tracings of individual images. It is impossible to tell from Creed's tracings what the context was, or the relationships of the individual images to each other. Unfortunately, any meaning conveyed by the overall grouping of images has been lost. Who was George Creed? George Creed was born 27 May, 1829 on the family farm at South Rawdon, in Hants County, Nova Scotia. He worked as a farmer, storekeeper and eventually Postmaster in South Rawdon. The Creed family had emigrated from Faversham, England and his grandfather, Richard Creed, was a clerk with the Royal Engineers and had been involved in construction work at the Halifax Citadel. He travelled extensively in the Maritimes and was very interested in the Mi'kmaq. Reading of the discovery of strange etchings in the rocks along rivers and lakeshores in Queens County, in James More's History of Queens County, Creed travelled to see the petroglyphs in 1881. He returned to Kejimkujik and made his first tracings there and at McGowan Lake in 1887. The following year, assisted by his wife and two nephews, he was able to stay longer making tracings of several hundred petroglyphs. "Accompanied by my wife as tent-keeper and matron, and my two nephews, Messrs. Frank S. Creed, of Fredericton, N.B., and Geo. W. Davison, of Newport, Queens, as assistants, I camped on the shore of Kejimkoojic (sic), on June 23. From that date until July 28 we worked assiduously at examining, tracing and copying whenever the favourable weather would permit. At the close of five weeks under canvas, the water having risen so as to prevent further progress, we resolved to abandon the work on Saturday, 28th July,..." From a talk given by Creed, and quoted in the Halifax Morning Chronicle, 14 November 1888. In 1888, Creed deposited a set of his tracings in the office of the Provincial Secretary. They were transferred to the Provincial Museum of Nova Scotia in 1910. A second set was given by Creed to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. George Creed died in 1899 and was buried in the graveyard on his farm, "Clifford Farm", in South Rawdon. A detailed history of the Creed Family can be found here at Ruth Davison's Genealogy pages.