approved

advertisement

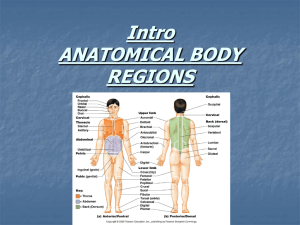

Ministry of Health of Ukraine BUKOVINIAN STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY “APPROVED” on methodical meeting of the Department of Anatomy, Topographical anatomy and Operative Surgery “………”…………………….2008 р. (Protocol №……….) The chief of department professor ……………………….……Yu.T.Achtemiichuk “………”…………………….2008 р. METHODICAL GUIDELINES for the 2nd-year foreign students of English-spoken groups of the Medical Faculty (speciality “General medicine”) for independent work during the preparation to practical studies THE THEME OF STUDIES “Topographical anatomy of inguinal region. Topographical anatomy and operative surgery of the inguinal hernias” MODULE I Topographical Anatomy and Operative Surgery of the Head, Neck, Thorax and Abdomen Semantic module 3 “Topographical Anatomy and Operative Surgery of the Abdomen” Chernivtsi – 2008 1. Actuality of theme: The topographical anatomy and operative surgery of the abdomen are very importance, because without the knowledge about peculiarities and variants of structure, form, location and mutual location of abdominal anatomical structures, their age-specific it is impossible to diagnose in a proper time and correctly and to prescribe a necessary treatment to the patient. Surgeons usually pay much attention to the topographo-anatomic basis of surgical operations on the abdomen. 2. Duration of studies: 2 working hours. 3. Objectives (concrete purposes): To know the definition of regions of the abdomen. To know classification of surgical operations on the abdomen. To know the topographical anatomy and operative surgery of the organs of the abdomenal cavity. 4. Basic knowledges, abilities, skills, that necessary for the study themes (interdisciplinary integration): The names of previous disciplines 1. Normal anatomy 2. Physiology 3. Biophysics The got skills To describe the structure and function of the different organs of the human body, to determine projectors and landmarks of the anatomical structures. To understand the basic physical principles of using medical equipment and instruments. 5. Advices to the student. 5.1. Table of contents of the theme: The Inguinal Region The inguinal region is very important surgically because it is the site of inguinal hernias ("ruptures") in both sexes; however, they are much more common in males. The inguinal region is an area of weakness in the anterior abdominal wall, especially in males, owing to the prenatal penetration of the wall by the testis and spermatic cord. The Inguinal Canal. This is an oblique passage, about 4 cm long in adults, through the inferior part of the anterior abdominal wall. It runs inferomedially, just superior and parallel to the medial half of the inguinal ligament. The inguinal canal has two walls (anterior and posterior), two openings (one at each end called the superficial and deep inguinal rings), a roof (superior wall), and a floor (inferior wall). The anterior wall of the inguinal canal is formed mainly by the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. It is reinforced laterally by fibers of the internal oblique muscle; sometimes by those of the transversus abdominis muscle. The posterior wall of the inguinal canal is formed throughout by the transversalis fascia, which is reinforced medially by the conjoint tendon, the common tendon of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. The floor of the inguinal canal is formed by the superior surface of the inguinal ligament and the lacunar ligament. The roof of the inguinal canal is formed by arching fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. The inferior epigastric artery lies at the medial boundary of the deep inguinal ring; hence, its pulsations form a useful landmark during surgery for determining the location of this ring. Owing to the obliquity of the inguinal canal, the deep and superficial inguinal rings do not coincide. Consequently, increases in intra-abdominal pressure act on the deep inguinal ring, forcing the posterior wall of the canal against the anterior wall. This strengthens this weak part of the anterior abdominal wall. The inguinal canal has been likened to an arcade of three arches formed by the three flat abdominal muscles. Contraction of the external oblique muscle approximates the anterior wall of the canal (formed mainly by the aponeurosis of the external oblique) to the posterior wall (formed mainly by the transversalis fascia). Contraction of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles makes them taut; as a result, the roof of the canal descends and the passage is constricted. During standing, these muscles continuously contract. During coughing and straining, the raised intra-abdominal pressure threatens to force some of the abdominal contents through the canal, producing a hernia. However, vigorous contraction of the arched fleshy fibers of the internal oblique and transverses abdominis muscles "clamp down." The action is like a halfsphincter that helps to prevent herniation. Immediately posterior to the superficial inguinal ring is the conjoint tendon; the rectus abdominis muscle is posterior to the conjoint tendon. When intra-abdominal pressure rises, the flat muscles of the abdomen contract, forcing the external oblique aponeurosis against the conjoint tendon, which then pushes against the rectus abdominis muscle. Hence, the conjoint tendon and rectus abdominis muscle reinforce the posterior surface of the superficial inguinal ring, tending to prevent herniation. The Superficial Ring of the Inguinal Canal. Although it is called a ring, the superficial (external) inguinal ring is a more or less triangular aperture (deficiency) in the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The base of this triangle is formed by the pubic crest and its apex is directed superolaterally. The sides of the triangle are formed by the medial and lateral crura (L. legs) of the superficial inguinal ring. Emerging from the superficial inguinal ring is the spermatic cord in the male and the round ligament of the uterus in the female. In addition, the ilioinguinal nerve makes its exit through the ring to supply skin on the superomcdial aspect of the thigh. The central point of the superficial inguinal ring is superior to the pubic tubercle. The lateral crus of the superficial inguinal ring is formed by the part of the external oblique aponeurosis that is attached to the pubic tubercle via the inguinal ligament. The spermatic cord rests on the inferior part of this crus. The medial crus of the superficial inguinal ring is formed by the part of this aponeurosis that diverges to attach to the pubic bone and pubic crest, medial to the pubic tubercle. Intercrural fibers from the inguinal ligament arch superomedially across the superficial inguinal ring. They prevent the crura from spreading apart. The superficial inguinal ring is palpable just superior and lateral to the pubic tubercle. In men it can be examined by invaginating the skin of the scrotum with the tip of a digit (often the index finger), and probing gently superolaterally along the spermatic cord. If the ring is enlarged, it may admit the digit without causing pain. In women and children, the dimensions of the superficial inguinal ring are much less than in men and palpation of it is difficult. In male infants the superficial inguinal ring does not normally admit the tip of a digit. The Deep Ring of the Inguinal Canal. This slitlike opening in the transversalis fascia is located just lateral to the inferior epigastric artery. This deep (internal) ring is immediately superior to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and medial to the origin of the transverses abdominis muscle from the inguinal ligament. The deep inguinal ring is the opening of a fingerlike diverticulum of the transversalis fascia. It formed prenatally when the processus vaginalis evaginated ("pushed through") the transversalis fascia. The margins of the deep ring are not sharply defined, as are those of the superficial ring. When the external oblique is reflected and the epigastric vessels are displaced, it ceases to exist as a ring; however, from the internal aspect, a dimple in the peritoneum often marks the site of the deep inguinal ring. Descent of the Testes. To understand the inguinal canal, some knowledge of the migration and descent of the testes is essential. The testes develop in the lumbar regions deep to the transversalis fascia, between it and the peritoneum. They normally pass through the inguinal canals into the scrotum just before birth. The site of the inguinal canal in the fetus is first indicated by the gubernaculum, a ligament that extends from the testis through the anterior abdominal wall and inserts into the internal surface of the scrotum. Later, a fingerlike outpouching or diverticulum of peritoneum, called the processus vaginalis, follows the gubernaculum and evaginates the anterior abdominal wall to form the inguinal canal. The processus vaginalis pushes extensions of the layers of the anterior abdominal wall before it. In males these prolongations of the layers of the anterior abdominal wall become the coverings of the spermatic cord. In both sexes the opening produced by the processus vaginalis in the external oblique aponeurosis forms the superficial inguinal ring. The testes usually enter the inguinal canals just before birth and pass inferomedially through them to enter the scrotum. Normally the stalk of the processus vaginalis obliterates shortly afterbirth, leaving only the part surrounding the testis, which becomes the tunica vaginalis. The scrotal ligament is the adult derivative of the gubernaculum. Maldescent of a testis (undescended testis or cryptorchidism) is a common abnormality. The testes are undescended in about 3% of full-term and 30% of premature infants. Undescended testes are usually located somewhere along the inguinal canal. Most undescended testes descend during the first few weeks after birth. Descent of the Ovaries. The ovaries also descend from their sites of origin on the posterior abdominal wall to a point just inferior to the pelvic brim; however, they do not normally enter the inguinal canals. The processus vaginalis normally obliterates completely and the gubernaculums attaches to the uterus, where it is divided into the ligament of the ovary and the round ligament of the uterus. The round ligament of the uterus passes through the inguinal canal and attaches to the internal surface of the labium majus (homologous to half of the scrotum). Persistence of the processus vaginalis in a female, called a canal of Nuck clinically, may result in an indirect inguinal hernia. Cysts in the inguinal canal and labium majus may also develop from remnants of the processus vaginalis. Summary of the Inguinal Canal. The inguinal canal is an oblique passage through the inferior part of the anterior abdominal wall. The chief protection of the inguinal canal is muscular. Its main constituent is the spermatic cord in males and the round ligament of the uterus in females. It contains the ilioinguinal nerve in both sexes. It has an opening at each end, the deep and superficial inguinal rings. The deep ring is a slitlike opening in the transversalis fascia and the superficial ring is a triangular opening in the aponeurosis of the external oblique. The inguinal canal has two walls (anterior and posterior), a roof, and a floor. The anterior wall is formed mainly by the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle and is reinforced laterally by fibers of the internal oblique. The posterior wall is formed mainly by the transversalis fascia and is reinforced medially by the conjoint tendon. The floor is formed by the inguinal and lacunar ligaments. The roof is composed of the arching fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 5.2. Theoretical questions to studies: The inguinal region. The layer structure of the inguinal region. The nerve and blood supplay of the inguinal region. Fascias of the inguinal region. Surgical anatomy of the inguinal hernias. Principles of surgical treatment of the direct inguinal hernias. Principles of surgical treatment of the indirect inguinal hernias. Principles of surgical treatment of the congenital inguinal hernias. 9. Principles of surgical treatment of the strangulated hernias. 10.Principles of surgical treatment of the sliding hernias. 5.3. Materials for self-control: 1. Diffuse pain referred to the epigastric region and radiating circumferentially around the chest is the result of afferent fibers that travel via which of the following nerves? A B C D E 2. Greater splanchnic Intercostal Phrenic Vagus None of the above In the patient described, the subsequent localization of the pain in the right hypochondriac region is the result of inflammatory stimulation of fibers that are extensions of which of the following nerves? A B C D E Greater splanchnic Intercostal Phrenic Vagus None of the above 3. The patient receives a general anesthetic in preparation for a cholecystectomy. A right subcostal incision is made, which begins near the xiphoid process, runs along and immediately beneath the costal margin to the anterior axillary line, and transects the rectus abdominis muscle and rectus sheath. At the level of the transpyloric plane, the anterior wall of the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle receives contributions from the A aponeuroses of the internal and external oblique muscles B aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles C aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis and internal and external oblique muscles D transversalis fascia E transversalis fascia and aponeu-rosis of the transversus abdominis muscle 4. At this level of incision, liga-tion of the superior epigastric artery probably will result in little, if any, necrosis of the rectus abdominis muscle because the superior epigastric artery anastomoses with the A B C D E 5. deep circumflex iliac artery inferior epigastric artery intercostal arteries internal thoracic artery musculophrenic artery Exploration of the peritoneal cavity disclosed a distended gallbladder. It is located A between the left and caudate lobes of the liver B between the right and quadrate lobes of the liver C in the falciform ligament D in the lesser omentum E in the right anterior leaf of the coronary ligament 6. Numerous stones could be palpated. A finger was inserted into the omental foramen (of Winslow), and the common bile duct was palpated for stones. Structures that bound the omental foramen include all the following EXCEPT the A B C D E 7. caudate lobe of the liver common bile duct hepatic vein inferior vena cava superior part of the duodenum Before closure of the incision, it is felt that a drain should be left in place in the abdominal cavity so that any leakage of bile from the sutured stump or from inadvertent injury to the duct system can be detected. This drain would most advantageously be located in the A B C D E omental bursa pelvic cavity pouch of Morison right paracolic gutter right subphrenic recess Literature 1. Snell R.S. Clinical Anatomy for medical students. – Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000. – 898 p. 2. Skandalakis J.E., Skandalakis P.N., Skandalakis L.J. Surgical Anatomy and Technique. – Springer, 1995. – 674 p. 3. Netter F.H. Atlas of human anatomy. – Ciba-Geigy Co., 1994. – 514 p. 4. Ellis H. Clinical Anatomy Arevision and applied anatomy for clinical students. – Blackwell publishing, 2006. – 439 p.