Characterization: All About The People We Meet

advertisement

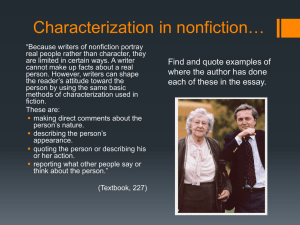

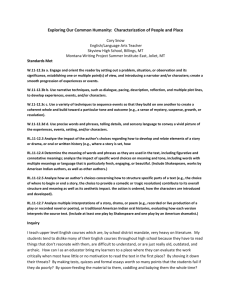

Characterization: All About The People We Meet by Mara Rockliff Getting to Know You Wouldn’t life be easier if the people you met just wore T-shirts that told you what they were like? You’d know right away if the girl who just moved in next door was “SNOBBY AND CONCEITED” or “FRIENDLY, WITH A GREAT SENSE OF HUMOR.” That substitute teacher? Better not mess with her—she’s “TOUGH BUT FAIR.” You won’t have to wonder whether your new science partner will be fun or annoying. His T–shirt says it all. Show Me a Story If you read a novel written a hundred years ago or more, the writer may just tell you directly, “Old Luther was the meanest old cuss in five counties,” or “Little Posy was barely half the size of the other orphans, but she had pluck.” Those kinds of statements, in which the writer tells you directly what a character is like, are known as direct characterization. These days, though, writers try to make their stories more like real life. Writers want you to get to know fictional characters just as you get to know people in real life—not by reading a statement on a T–shirt, but by observing people very closely and deciding for yourself what kinds of people they are. You ask: What do they look like? How do they act? What do they say and how do they say it? How do other people feel about them? One of the first pieces of advice a new writer always hears is “Show, don’t tell.” Telling is the old way—direct characterization. Most writers (and readers) think showing is more interesting and realistic than just telling. This “showing” method of revealing a character is called indirect characterization. In indirect characterization you have to observe the character and come to your own conclusion about the kind of person you are meeting. Who Is This Character, Anyway? So how does a writer show what a character is like? 1. Appearance. Appearances can sometimes deceive, but they’re often your first clue to character. Does the grandfather in the story have laugh lines around his eyes or a furrowed brow from years of worrying? Is the trial lawyer cool and collected in her expensive, neatly pressed suit, or is she a sweat-soaked, wrinkled mess? 2. Action. The writer could tell you, “The boy was happy,” but if you see the boy in action, you’ll know for yourself. Luis danced into the kitchen, singing along with the song on the radio. He paused just long enough to give his mother a loud kiss on the cheek, then danced on out the door. 3. Speech. Listen to a character talk, and she will tell you what she’s like– indirectly. A four-year-old may not announce, “Hi! I’m bratty and stubborn,” but doesn’t the following outburst reveal the same thing? “I don’t have to do what you say!” screamed Darlene as she kicked the new baby sitter in the shins. 4. Thoughts and feelings. Here’s where literature is better than life. In some books you can actually read what people are thinking, and what they think shows who they are. Julie wanted to cry when she saw the stray cat. Its ribs were showing. She desperately wanted to add it to her well-fed tribe of cats at home. 5. Other characters’ reactions. What do the other people in the story think of this character? What do they say about her? How do they act toward him? Of course, just as in life, you have to consider the source. If a character has something insulting to say about everyone in his school, his comments probably tell you more about him than about the others. PRACTICE Write down the name of a character from a story you have recently read. Choose two or three words that describe that character, write those words under the name, and then draw a circle around each word. Now, go back to the story, and find examples of how the writer shows you those characteristics. (Notice appearance, action, speech, thoughts, and other characters’ reactions.) Jot down the examples, circle them, and draw lines connecting them to the main circle.