THREE APPROACHES TO CASE STUDY DEVELOPMENT FOR

advertisement

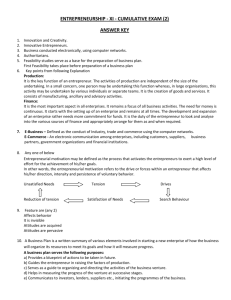

THREE APPROACHES TO CASE STUDY DEVELOPMENT FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION Mary C. Gentile and Heidi M. Neck (This is a working draft. Please do not distribute or reproduce without permission.) Case studies used for teaching purposes are usually written narratives that present a particular business situation or decision, although video and web-based products are growing in popularity, either as supplements or replacements for the written document. Typically cases are fact-based, although sometimes the actual actors, organizations and data are disguised and occasionally a fictional case will be created to illustrate a particular hypothetical scenario for teaching purposes. Case studies can be used as marketing tools, archival documents, or as the basis of scholarly research, but here the focus is on educational case studies for an Entrepreneurship curriculum. Thus, these cases are presented in a way that facilitates a focused and fact-based discussion on topics such as opportunity identification, opportunity evaluation, resource acquisition, entry and growth strategies, creative problem solving, team building, family enterprising, innovation, financing, or the harvest event. And very importantly, the case developers have a defined set of learning objectives that drives their decisions about what information to include and exclude, and how to structure and present the case itself. It is useful to note that defined "learning objectives" do not necessarily translate into defined "solutions" or answers to the case challenges. A case-writing recipe does not exist. Though the Harvard Business School case tradition is well known throughout business education, a monolithic case writing methodology is not encouraged for teaching entrepreneurship. The study of entrepreneurship involves understanding how opportunities are discovered, created, and exploited by whom and under what circumstances.1 Given the multidisciplinary nature of the field and the multiple foci demanded to reflect the variability, flexibility, and uncertainty associated with entrepreneurship, an entrepreneurship-case writer is encouraged to think beyond the “traditional” case study to better reflect the true practice of entrepreneurship and help students work to develop empathy for the entrepreneur. As a starting point, let’s consider three types of entrepreneurship teaching cases: 1 Venkataraman, S. (1997). The dinstinctive domain of entrepreneurship research. In J. Katz & R. Brockhaus (Eds.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, and Growth (Vol. 3, pp. 119-138). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. 1 (1) Opportunity Creating Cases2 The opportunity creating case study focuses on the process of creating a suitable opportunity for an entrepreneurial venture. This type of case is very much centered on the entrepreneur, the entrepreneurial team, and associated networks. It is less about the actual opportunity, although it may be present, and more about the act of creating or making an opportunity. It is both possible and probable that the entrepreneur(s) featured in the case may not even have a venture idea but simply want to engage in the process of creating something of value. Typically, however, the case introduces an individual entrepreneur and describes his/her interests and context, and the focus of the classroom discussion is on what venture(s) the the entrepreneur might start, and how he/she might do so . Such a case approach is appropriate for the development of an entirely new organization, or the development of a new offering within an existing organization. The opportunity-creating case can be structured as a more traditional decision-making case (format described below), or it can be written more informally as a sort of straightforward and hopefully compelling "story" – a sort of opportunity biography. The key factors in this type of case are that the protagonist is an entrepreneur (or a prospective one); the story concerns the entrepreneur's journey in deciding to start a venture and figuring out what it will be; and the case includes enough information so that the discussants can identify and dialogue about the motivation, ability, resources and potential opportunities of the entrepreneur. The approach for writing and teaching opportunity-creating cases is grounded in the Effectuation Approach to entrepreneurship presented in the research and writing of Professor Saras Sarasvathy of the University of Virginia’s Darden Graduate School of Business. The Effectuation approach is contrasted with a more causal approach to venture creation. A traditional scenario found in many entrepreneurship courses and cases starts from the assumption that an entrepreneur simply discovers or finds an opportunity. Then the entrepreneur conducts an analysis to predict the size of the opportunity and the resources required to realize it; creates a plan; and acquires resources to start the venture. The case story follows a chain of causal reasoning, from opportunity discovery through to launch. Rather than starting with a defined opportunity and attempting to predict all contingencies in advance of action and thereby control for them, an effectuation approach suggests that an entrepreneur focuses upon understanding all the means and resources available and then to imagine as many opportunities as possible. In other words, the entrepreneur seeks to act quickly, determine what can be done next, given the means at hand, and to understand what he/she can afford to lose rather than what the risk/return ratio may be. As a result, the analysis of this sort of opportunity-creating case is organized around the following four questions: 2This form of case is heavily influenced by the work of Dr. Saras Sarasvathy and her entrepreneurship theory of Effectuation. For a comprehensive description see: Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise. Northampton, MA: Elgar. 2 Who is the entrepreneur? What does the entrepreneur know? Whom does the entrepreneur know? Then, based on the answer to the above three questions, what should the entrepreneur do? Thus an opportunity-creating case can focus on what the entrepreneur should do first, or next, to start the venture or what opportunity the entrepreneur should explore. The above four questions allow discussants to identify the field of potential opportunities or pathways to start up that the case protagonist has before him or her, based on the entrepreneur's personal, experiential, intellectual and relational resources. The idea here is to be open-ended; to allow for the generation of as many ideas as possible; to follow potential leads as far as the available or obtainable resources will allow; and to be constrained only by a definition of "affordable loss" as opposed to a pre-defined "projected gain." This type of analysis provides students with the opportunity to actually practice the flexibility, freedom, creativity and rapid response times that real-life entrepreneurs must possess, especially during the emergent stages of an idea or venture. The discussion plan will be one of opening up the conversation to generate – and examine – multiple ideas and potential venture objectives, or paths to launch, through the process of creating as opposed to finding – the "Bird-in-Hand" approach. Additionally, the discussion plan for an opportunity creating case might be organized around the question "What can the entrepreneur afford to lose?" or the question "Who are the networks that the protagonist can tap/partner with?" or "How can the entrepreneur" work with, rather than against, the challenges and obstacles that present themselves?" Each of these teachable questions reflects one of the principles of creation-oriented behavior that Sarasvathy has identified in her studies of successful entrepreneurs (Figure 1). Table 1 Principles of Creation-Oriented Behavior Principle Meaning What it’s not… Bird-in-Hand Principle Start with Who you are, What you know & Whom you know Starting with pre-set goals Affordable Loss Principle Invest in what you can afford to lose – extreme case $0 Predicting expected return Crazy Quilt Principle Build a network of selfselected stakeholders Competitive Analysis Lemonade Principle Embrace and leverage surprises Fearing failure or avoiding surprises Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise. Northampton, MA: Elgar. 3 The teaching and writing of an opportunity-creating case is not devoid of market understanding and analysis; they are just not the primary emphasis. Dew and colleagues3 offer another framework (Figure 1) that can be used in the discussion of an opportunitycreating case and that illustrates the relationship of this type of market analysis to the examination of the individual entrepreneur's opportunity creation behaviors. In creating an opportunity, personal feasibility and personal value are fundamental to venture creation. If the entrepreneur (individual) and opportunity align, then logic follows that market, technical, and financial feasibility must also then be considered in light of the entrepreneur's ability and motivation. But in-depth examinations of market feasibility and value will normally take places in the discussion of decision-making cases(descibed below). Although sometimes the same text can be used as anopportunity-creating case and also as a decision-making case, the teaching objectives and focus of the classroom discussion would be significantly different. Figure 1 Is an idea a good opportunity? FEASIBILITY VALUE Is it doable? Technical feasibility Market feasibility Is it worth doing? Financial feasibility (affordable loss) Can I do it? PERSONAL What does it take? Who else do I need? Do I want to do it? What excites me about it and why? MARKET Source: Dew, Read, Sarasvathy, Wiltbank, & Ohlsson, Effectuation in Action, Work in progress, March 2009, p. 36. (2) Decision-Making Cases The decision-making case study is very much inspired by the Harvard case writing tradition. This type of case generally focuses on a particular business process challenge or functional area analysis, while set within an entrepreneurial venture. Most often, however, the decision-making case in entrepreneurship courses documents the journey of venture creation and students must apply analytical tools and frameworks in order to assess, select and justify a decision to act in a particular way... In other words, through a decision-making case students should be prepared to answer: What do the market factors, competitor analyses and financial projections tell me about the potential profitability and viability of this opportunity at a certain point, and how best to realize them? 3 Dew, Read, Sarasvathy, Wiltbank, Ohlsson, Effectuation in Action, Work in progress, March 2009 page 36/88. 4 Beyond this overarching question, there is a problem to be solved or a critical decision point. Decision-making cases move from a discussion of the opportunity to a statement of a problem or decision challenge and an implicit or explicit question about "what should the entrepreneur do?" In order to evaluate options and formulate a decision, the case analysis requires the application of specific techniques, evaluation/analysis methods, strategic frameworks, etc. Some of these techniques, methods and frameworks are specific to entrepreneurial situations (e.g., venture funding models, valuation, hiring employees, building a team, market entry strategy, evaluating resources, intellectual property) and some of them are more generic business tools (e.g., break-even analysis, financial statement analysis, industry analysis). This type of case study is less about uncovering or creating new ground than it is about managing effectively within the terrain that the entrepreneur has already identified and many actions have taken place prior to the point where a decision is required. As such a decision-making case includes a significant amount of background on the key decisionmakers, the organization, the context and any relevant financial or other data, either in the body of the case or in appendices. The traditional decision-making case study is typically shaped and framed from the perspective of a single case protagonist (e.g., the entrepreneur). Specific questions are highlighted, simply because they are the questions for which the entrepreneur or entrepreneurial team was responsible. For example, a typical Babson decision-making case introduces the entrepreneur and the idea that formed a venture. There is enough information in the case to evaluate the attractiveness of the opportunity at the time of venture creation but then the entrepreneur is challenged in some way. Students might use the contextual, competitor and customer data provided to design an initial marketing approach; or they might use the financial data provided to define the initial investment levels required to launch the concept. The standard Babson framework used in decision-making cases is the Timmons Model created by the late Babson professor, Jeffry Timmons.4 Figure 2 depicts the basic model as having three main components: the opportunity, the resources, and the team. This simple but powerful model is a useful guide for both writing and teaching a decisionmaking case. The students should view the Timmons Model as an entrepreneur juggling three balls – opportunity, resources, and team. In an ideal state all three balls should be the same size and easy for the entrepreneur to juggle but in most situations there is an imbalance. The opportunity may be significant in size (large opportunity circle) but there are few resources available to act (small resources circle) and the team is lacking some important skills (medium team circle). At any given point in the case students should be able to evaluate all three components and make a decision about the viability of the venture and/or how to enhance it. Additionally analyzing the case using the Timmons model is a nice way to codify the information presented and helps students navigate through the important decision point(s) 4 For a more comprehensive view of the Timmons model see Chapter 3 in J. Timmons & S. Spinelli (2009) New Venture Creation, McGraw-Hill. 5 highlighted in the case. Achieving balance between the three components in this model will be influenced by the behavior, mindset and skillfulness of the case protagonist – that is, by the creativity, communication, and leadership of the particular entrepreneur. And the business planning process is a good exercise to identify the fits and gaps of the venture and where the imbalance may be and what is needed in order to regain balance. Again, the goal is to keep the model in balance and have the circles equal in size. It is a classroom tool that is both visual and analytical. Figure 2 Timmons Model of Entrepreneurship Communication Opportunity Resources Business Plan Fits and gaps Creativity Leadership Team Founder Though these are actions that may seem relevant for an opportunity-creating case, it is important to remember that there is little analysis in the opportunity-creating case from market, industry, and financial perspectives. The decision-making case requires the use of data, market research, and business planning tools to decide if the entrepreneur should have started the venture or not and what options should be pursued in the future. Based on historical analysis, using the Timmons model, student attempt to predict the future and make decisions accordingly. The Timmons model, when used to frame a decisionmaking case, serves to help student evaluate options. On the other hand, the opportunity-creating case serves as a vehicle to help students learn to identify and create all the options. Figure 3 illustrates the flow of the two types of cases and subsequent case discussions. The decision-making case narrows; the opportunity-creating case expands. 6 Figure 3 Decision-Making versus Opportunity-Creating Case Flow Decision-Making Cases narrow down options, evaluate, and make decisions. Every input (actions, information, resources) expands the possible opportunities available. Entrepreneurial Thinking information analyzed to Managerial Analysis Large amounts of Opportunity-Creating Cases A widely accepted decision-making case format includes: a brief opening that presents the case "problem" or decision focus; discrete background sections on the company, the case protagonist, and the industry; background sections on any other relevant players or constituencies (e.g., competitors, suppliers, consumers, other members of management, other employees, investors, partnering organizations, relevant government or community bodies, etc.); a chronological narrative of the situation being described which concludes where the case originally began – that is, with a statement of the case "problem" but without a decision. Sometimes a brief follow-on "B" case is prepared that provides a description of what actually happened. These cases are typically 15-20 pages long and can include numerous appendices and exhibits which present relevant background documents, financial reports, market research data, and so on. The more compelling and challenging the decision point, the more impactful the case study will be. In fact, deciding on a decision focus is often the hardest part of writing a good decision-making case. It should be focused enough that the student preparation and faculty teaching plan can be quite specific. However, it should be the kind of problem that once engaged, requires one to examine many streams of data and to consider multiple possible scenarios. The best decision-making cases can support more than one plausible response, although there should also be some clearly less optimal responses, such that students can hone their analysis and logic by going down multiple paths and the occasional dead end. In other words, the decision should not be one that is obvious and that the entire class will agree with early on in the case discussion. Increasingly, educators have begun to experiment with variations on the traditional decision-making case study. Babson College, for example, uses collaboration tools, specifically wikis, to build cases in real time. The professor creates the base case but then company management, industry experts, and other stakeholders add and edit content as well as answer student questions that are posted. Students, professors, and practitioners 7 are all collaborating and interacting to build case content, exchange ideas, and test alternatives.5 Another trend capitalizes on readily available and current information found on the web. Instead of providing all the relevant data, pre-packaged as it were, case developers will craft the problem statement and then gather web-links to a variety of different types and sources of background information.6 More data will be made available in this way than one individual student could possibly assimilate, requiring students to make judgments about which data is salient and most important and which information they may safely ignore, and/or to work in teams where different individuals are responsible for different aspects of the problem to be solved. These cases are intended to be more reflective of real life, since typically entrepreneurs are not handed all the relevant information in a neat 15 page document. (3) Implementation/Scripting Cases Like the decision-making case, the implementation/scripting case study7 focuses upon a particular business challenge, set within an entrepreneurial venture, and presents the situation from the perspective of an individual case protagonist or actor – usually the entrepreneur but can be other stakeholders. Unlike the previous two types of cases, however, the implementation/scripting case study ends at the point where the protagonist has already decided what to do and needs to build an action plan and a script to get it done. The focal questions therefore are "how can the case protagonist get this done? what information will be needed? what arguments will be effective? what allies are needed? what steps should be taken, in what sequence?" and so on. Implementation/scripting cases are presented as narratives or stories, following the case protagonist's thinking about a particularly compelling challenge and sharing enough detail about who the protagonist is such that discussants can understand the strengths and challenges that he or she will bring to the situation. Often the case will end with the need for the protagonist to persuade certain target audiences to get on board with a decision and students will spend time developing actual scripts for how he or she can be most persuasive. The implementation/scripting case study is typically much briefer than the other two types of cases described here. It may be as brief as a paragraph or as long as 3 or 4 pages. Because the cases are shorter, they are more suggestive, relying on the students' own experience and knowledge, as well as outside research (reading, practitioner interviews, etc.). For this reason, students often benefit from team preparation of their action plans, so that they can share different data-gathering/research or interviewing tasks and also use Iyer, B. R., Parise, S., McGuire, M., & Santiage, E. “Babson College’s Wiki-based Platform for Innovative Case Development.” Paper presented at the 2008 Organization Behavior Teaching Conference, Wellesley, MA. 6 For example see information on Yale’s “raw” cases at http://mba.yale.edu/news_events/CMS/articles/pdf/RawvsCooked.pdf 7 This case model is based upon the case format and approach developed by Mary C. Gentile Ph.D, for the Giving Voice to Values curriculum (www.aspenCBE.org). 5 8 peer coaching and brainstorming to generate effective and persuasive "scripts" for building support for the protagonist's decision. Implementation/scripting cases pertaining to the entrepreneurship process may include topics such as succession issues in family enterprising, the first time an entrepreneur must fire an employee, and countless ethical dilemmas faced by entrepreneurs. The implementation/scripting cases are ideal for emotional challenges faced by entrepreneurs. An implementation script case allows for the effective facilitation of sometimes highly charged, emotional discussions. The analysis, discussion and resolution of implementation/scripting cases typically follow a simple process by answering the following questions: What is your purpose in pursuing this decision? What kind of information do you need in order to plan and act responsibly and effectively in the pursuit of your purpose? What are your action options and what do you need to be successful? What is at stake for each affected party, including the protagonist and the parties he or she wants to persuade? What are the main arguments or the typical "reasons and rationalizations" the protagonist is likely to encounter as objections to his or her decision? What are the most effective responses ("scripts") or "levers" that case protagonist can use to counter those objections? When preparing and sharing their scripts, students should be encouraged to go beyond their first line of argument, anticipating what their target audience might say in response, and then developing follow-up scripts. Therefore, they are developing a kind of decision-tree of responses. Taking all the above into consideration, what will be the most effective action plan – target audiences; sequence; context; etc.? Although the cases themselves are brief, implementation/scripting cases often require just as much research and preparation by their authors as the other case formats. However, much of this information is analyzed and presented in the teaching notes, as opposed to the case study document itself. Conclusion The three types of case studies described above provide a defined yet flexible framework for the development of case teaching materials for an entrepreneurship curriculum. It is important to note that one format is not better than the other. What is most important, however, is that the educator has an understanding of which case type to use when (in their teaching) and what case issue is most appropriate for each form (when writing). Table 2 provides an overview and can act as a helpful guide for both case writing and teaching. Entrepreneurship is a multifaceted process with different actors (e.g., entrepreneurs, team, stakeholders) and artifacts (e.g., assets, resources, venture design, business plans, business models); thus, a comprehensive and similarly multi-faced case approach will optimize student learning and entrepreneurial development. 9 Table 2 Summary of Entrepreneurship Case Study Types Approach Teaching Objective Effectuation Engage students in the process of creating Type Implementation/ Scripting What does the entrepreneur say? How can the entrepreneur get it done? What information is needed? Persuasion Engage students in the process of scripting and action planning Best for… Discussing the emergent side of entrepreneurship Working through challenging situations at startup and beyond Length Short/Medium/Long Short Focal Questions Opportunity Creating Who is entrepreneur? What does the entrepreneur know? Whom does the entrepreneur know? Decision Making What’s the problem or opportunity? What are the options? What’s the best decision? Causation Engage students in the process of managerial decision making? Using or demonstrating analytical tools for analysis Long 10

![Chapter 3 – Idea Generation [ENK]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007787902_2-04482caa07789f8c953d1e8806ef5b0b-300x300.png)