Travis, F.T. (2006) From I To I: Concepts of Self on an

advertisement

NOTICE: this is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication in

The Concept of Self in Psychology, Nova Publishing. Changes resulting from the

publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and

other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may

have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive

version was subsequently published in Travis, F.T. (2006) From I To I: Concepts of Self

on an Object-Referral/ Self-Referral Continuum, In A. P. Prescott, Ed. The Concept of Self

in Psychology, Nova Publishing

FROM I TO I:

CONCEPTS OF SELF ON A

OBJECT-REFERRAL/ SELF-REFERRAL CONTINUUM

Fred Travis

Center for Brain, Consciousness and Cognition

Maharishi University of Management

1000 North Fourth Street, FM 1001

Fairfield, IA 52557

641 472 7000 x 3309 (phone)

641 472 1123 (fax)

Email: ftravis@mum.edu

Key words: Self, Transcendental Meditation, self-referral, object-referral, levels of mind,

cognition

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

ABSTRACT

Concepts of self in the 100-year history of psychology can be placed along an objectreferral/self-referral continuum. For instance, William James’s self-as-known, or “me,” is

more object-referral and his self-as-knower, or “I,” is more self-referral. Current neural

imaging studies have investigated 3rd person-perspectives of self (object-referral) and 1st

person-perspectives of self (self-referral).

The object-referral/self-referral continuum is based on analysis of individuals practicing

the Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique. This meditation technique from the Vedic

tradition of India takes the attention from surface perception and thinking, to more abstract

levels of thought, to a level of pure self-awareness at the source of thought. Our research

has yielded subjective and objective markers of the experience of pure self-awareness or

content-free self-awareness. Subjectively, pure self-awareness is characterized by the

absence of time, space and body sense. Time, space and body-sense are the framework for

waking experiences. During the experience of pure self-awareness, this framework that

gives meaning to waking consciousness is absent. Objectively, pure self-awareness is

characterized by spontaneous periods, 10-40 sec long, of slow inhalation along with

heightened brain wave coherence. These data support the Vedic descriptions of pure selfawareness as “the fourth”—a state of consciousness in addition to waking, dreaming and

sleeping.

Our research has also yielded subjective and objective characteristics of the permanent

integration of pure self-awareness with customary experiences during waking, dreaming,

and sleeping. This state has been traditionally called enlightenment. A content analysis of

inner experiences of these subjects and two comparison groups has yielded descriptions of

2

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

the ends of this object-referral/self-referral continuum. On the object-referral end,

individuals described themselves in terms of cognitive and behavioral processes. They

exhibited lower values of the consciousness factor, lower frontal EEG coherence during

tasks, lower alpha and higher gamma power during tasks, and less efficient cortical

preparatory. In contrast, individuals reporting the experience of enlightenment described

themselves as an abstract continuum underlying thought, feeling and action— self-referral

descriptions. The experience of self-awareness has been written with a capital “S”—Self—

to differentiate from more active experiences. These subjects exhibited higher values of

the consciousness factor, higher frontal coherence, higher alpha and lower gamma power

during tasks, and heightened cortical response to tasks. This object-referral/self-referral

continuum describes the progressive de-embedding of the Self from the machinery of

perception, thought, and behavior.

In the coming century, psychology should take advantage of meditation technologies—

technologies of consciousness—to explore more expanded experiences of Self to

understand who we are and what it means to be fully human.

3

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

INTRODUCTION

The concept of self has been a core concept throughout the 100-year history of

psychology. For instance, Wilhelm Wundt, the father of experimental psychology, defined

the self as a unitary concept: “…the feeling of the interconnection of all single psychical

experiences.” ((Wundt, 1897) pg. 221). In contrast, William James, the father of

American Psychology, delineated a range of possible concepts of self. These ranged from

the self as knower, the “I,” to the self as known, the “me” (James, 1962). The self-asknown includes our material processions, social status, thoughts and feelings (James,

1962).

Current neural imaging studies have investigated a similar continuum from 1st person to

3rd person perspectives of sense-of-self. Visualizing ones’ physical traits and bodily

gestures, a 3rd person perspective, activated medial parietal cortices including the precuneus

and angular gyrus (Kjaer et al., 2001; Taylor, 2001). Stories containing 1st person pronouns

activated medial frontal areas including the anterior cingulate (Vogeley et al., 1999).

Similarly, medial frontal activation was reported during 1st person self-referential

judgments of pictures (Gusnard et al., 2001) and of trait adjectives (Kelley et al., 2002).

Neural imaging data suggest that a distributed frontal-parietal system supports our

experience of self-awareness, with 1st person experiences activating predominately frontal

midline structures and 3rd person experiences activating predominately parietal midline

structures.

Our proposed object-referral/self-referral continuum of sense-of-self adds a level of self

that is independent of thinking and acting. This object-referral/self-referral continuum

(Travis et al., 2002) was based on interview data and EEG data of individuals practicing the

4

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Transcendental Meditation (TM®) technique1. This meditation technique is from the

Vedic tradition of India. It takes one’s attention from surface perception and thinking to a

level of pure consciousness at the source of thought (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1963). Pure

consciousness is the experience of consciousness itself—self-awareness without customary

thoughts, feelings or perceptions (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969; Travis et al., 2000). Pure

self-awareness is the state in which the self is only aware of itself. This contrasts with

object-referral awareness, in which the self is identified with the processes of knowing—

feelings, decisions, planning, thinking, comparing, perception and action. This state of

pure self-awareness is often written with a capital “S” to distinguish this more universal,

unbounded state of Self from the experience of being absorbed in thinking, planning and

activity.

SECTION 1:

WHAT IS THE NATURE OF THE EXPERIENCE

OF PURE SELF-AWARENESS?

We’ll begin with the Oxford English Dictionary definition of awareness. The first five

definitions in the dictionary define awareness with specific content: (1) interpersonal

cognitive relations, (2) remembering on a first-hand basis ones past actions or experiences,

(3) awareness of any object; (4) immediate awareness of ones mental processes, and (5) the

totality of mental experiences that constitute our conscious being. These definitions

characterize self-awareness is terms of the content of experience. The last definition is

qualitatively different: “…awareness that is distinct from the content that makes up the

stream of consciousness.”

1Transcendental

Meditation is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, licensed to Maharishi

Vedic Education Development Corporation, and used under sublicense.

5

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

A number of authors have defined states that could fall into this last definition of

awareness. O’Shaughnessy suggested that awareness itself can be "...distinct from

particular consciousnesses or awarenesses” ((O'Shaughnessy, 1986), p. 49). He proposed

that pure self-awareness is like an “empty canvas” that can not be viewed

representationally, but makes possible and is physically necessary to view a painted

picture. Woodruff-Smith discussed “the inner awareness that makes an experience

conscious...a constituent and constitutive feature of the experience itself” ((WoodruffSmith, 1986) p. 150). Baar’s theater metaphor includes an attention director or deep self

that provides a context (framework) to connect one conscious event with another (Baars,

1997).

The prevailing Western view is that an individual cannot be aware or conscious without

being conscious of something (Natsoulas, 1997); that no subjective state can be its own

object of experience ((James, 1962) pg. 190). However, the subjective traditions of the

East—the Vedic tradition of India (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969), and the Buddhist

traditions of China (Chung-Yuan, 1969) and Japan (Reps, 1955)—include systematic

meditation techniques predicted to lead to the state of "pure self-awareness" without

customary content of awareness. For instance, the Maitri Upanishad 6:19 (Upanishads,

1953) states:

When a wise man has withdrawn his mind from all things without, and when his

spirit of life has peacefully left inner sensations, let him rest in peace, free from the

movements of will and desire…Let the spirit of life surrender itself into what is

called turya, the fourth condition of consciousness. For it has been said: There is

something beyond our mind, which abides in silence within our mind. It is the

supreme mystery beyond thought. Let one’s mind . . . rest upon that and not rest on

anything else.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969), responsible for bringing the

TM technique to the West from the Vedic tradition of India, explains:

6

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

When consciousness is flowing out into the field of thoughts and activity it

identifies itself with many things, and this is how experience takes place.

Consciousness coming back onto itself gains an integrated state….This is pure

consciousness. (pg. 25)

Pure consciousness is “pure” in the sense that it is free from the customary processes and

contents of knowing. It is a state of awareness in that the knower does not black out. There

is no gap in time. Being or pure self-awareness is maintained. The content of this

experience is self-awareness. The Self serves both as the experiencer and the object of

experience. In contrast, during customary waking experience, the experiencer and the

object of experience are different. During customary waking experience, there is an inner

reality who is experiencing outer objects or inner thoughts and feelings.

The Buddhist tradition does not speak of an expanded state of Self-awareness. They

characterize deep experiences during their meditation practice to be “Nothingness” or

“Emptiness” (Shear et al., 1999). In contrast, the Vedic tradition characterizes pure

consciousness as the expansion of the individual self to its most universal status (Maharishi

Mahesh Yogi, 1963; Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969). Thus, to investigate the nature of an

expanded sense of Self, we studied individuals who practiced the TM technique, which is

based in the Vedic tradition. TM subjects are also well suited to this study because

individuals quickly master transcending during TM practice—after a few months practice

(Travis et al., 1999; Travis et al., 2002; Travis et al., in review) in comparison to years of

practice required with other meditation techniques before becoming expert (Compton et al.,

1983; Lutz et al., 2004). Thus, most TM subjects would be having similar experiences

reducing variability in the data. Focusing research subjects practicing a single meditation

technique, controls for different meditation experiences, and allows well-defined research

into the nature of self-awareness.

This paper first summarizes previously published research on subjective and objective

markers of the experience of pure self-awareness in TM subjects. It then reviews

subjective and objective markers of the permanent integration of pure self-awareness with

7

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

waking, dreaming and sleeping. Following this review of the literature, the proposed

object-referral/self-referral continuum of self-awareness is discussed in detail.

SECTION II:

PURE SELF-AWARENESS

DURING MEDITATION PRACTICE

Physiological Correlates

Changes in EEG, breath rate, skin conductance, and heart rate characterize the state of

pure self-awareness during TM practice. Refined breathing was the first published marker

of this experience. Farrow and Hebert (Farrow et al., 1982) and later Badawi and

colleagues (Badawi et al., 1984) observed suspension of normal respiration from 10 to 40

seconds during pure self-awareness experiences. This type of breathing, while initially

termed “respiratory suspension,” is actually an example of slow, prolonged inspiration

(Kesterson et al., 1989). This type of breathing is supported by different respiratory drive

centers in the brain stem then those that drive breathing during waking {Travis, 1997 #27;

Plum, 1980 #115}.

A second reliable marker of this state are skin conductance responses at the onset of

breath changes (Travis et al., 1997). This autonomic response is similar to that seen during

orienting—attention switching to environmental stimuli that are novel (Sokolov, 1963;

O'Gorman, 1979) or significant (Maltzman, 1977; Spinks et al., 1985). These autonomic

responses could mark the transition of awareness from active thinking processes to pure

self-awareness devoid of customary content.

A third marker, which is less obvious but has been reported in most studies, is a trend

for increasing frequency of the peak power in the EEG. Compared to the period prior to the

experience of pure self-awareness, the frequency of peak power of the EEG increases from

0.5 to 1.5 Hz. Fluctuations in frequency of peak power follow fluctuations in alertness.

For instance, during sleep 1 Hz EEG is seen, while during very focused tasks 40 Hz EEG

8

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

activity is reported. The observed increase in frequency of peak power during respiration

suspensions could be associated with increased alertness during this experience.

These changes in EEG power occur on the background of high global EEG coherence.

Coherence represents level of connectedness between different brain areas (Florian et al.,

1998; Pfurtscheller, 2001). Higher EEG coherence is associated with higher emotional

stability, higher moral reasoning, more inner motivation, and lower anxiety (Travis et al.,

2004). Alpha EEG coherence rises to a high level in the first minute of TM practice and

continues at that high level through the rest of the session (Travis et al., 1999). Recent

research also reports higher frontal/parietal phase synchrony during TM practice (Hebert et

al., in press). This unique constellation of physiological patterns is unlike any seen in

normal waking, sleeping, or dreaming.

Phenomenological Analysis

Fifty-two University students, twenty-six males and twenty-six females, were asked:

"Please describe the fine details of your deepest experiences during practice of the

Transcendental Meditation technique. Please describe them in your own words, just as if

you were describing the experience of eating a strawberry — its sweetness, juiciness, etc."

(Travis et al., 2004). We emphasized that we were interested in what they experienced; in

how it felt to them, and that we were not interested in other people’s descriptions of these

experience. We did not ask for descriptions of pure self-awareness. That would have

elicited biased responses reflecting more what they knew about pure consciousness, rather

than their direct experience of this state. They were allowed to write as much and for as

long as they wished. These subjects were an average age of 22.5 yrs (SD 6.9). They had

been practicing the TM technique for an average of 5.4 yrs (SD 5.0).

9

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Data analyses

The descriptions were analyzed using the guidelines for systematizing

phenomenological analysis proposed by Hycner (Hycner, 1985). This procedure begins

with reading the passage (all 52 descriptions) many times to get "a sense of the whole."

Next, Hycner recommends reading through and bracketing out "units of meaning"—words

or phrases which express a unique and coherent idea. Once the units of meaning had been

identified, then, as Hycner recommends, units that were clearly redundant were eliminated.

Next, the units were clustered by "shared meanings." This was done by explicit and

implicit meaning. From these clusters of shared meaning, general themes were identified.

The final step was to re-read the descriptions and tally the occurrence of the themes. This

yielded the number of subjects who included that theme in their descriptions, expressed as

a percentage of total subjects.

Results

Three major themes emerged from this analysis. Sixty-eight percent of the subjects

explicitly characterized deep experiences during practice of the Transcendental Meditation

technique by the absence of space, time, or body-sense. The other two themes—peaceful

(32%) and unboundedness (20%)—implicitly include the lack of boundaries of space, time

and body-sense, but further describe the experience when these boundaries were absent.

For instance, one subject described the experience of pure self-awareness as:

...a couple of times per week I experience deep, unbounded silence, during which I

am completely aware and awake, but no thoughts are present. There is no

awareness of where I am, or the passage of time. I feel completely whole and at

peace.

The content analysis of deep experiences during practice of the TM technique suggest

that pure self-awareness, consciousness itself, is qualitatively different than other waking

experiences. Time, space, and body sense are the framework for understanding waking

experience. Experiences either occur inside or outside of the body. Experiences contain

10

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

changing perceptual content that change over time and occur in different points of space.

During the experience of pure self-awareness, both the fundamental framework—time,

space and body sense—and the content of waking experience were absent. This suggests

that pure self-awareness is not an "altered" state of waking. It is not a distorted waking

experience. Rather, pure self-awareness is marked by the absence of the customary

qualities and characteristics of waking experience. Pure self-awareness is Self-awareness,

the Self, isolated from the processes and objects of experience.

Pure self-awareness is subjectively and objectively distinct from experiences during

customary waking, sleeping, and dreaming. In the Vedic tradition, pure self-awareness is

called “the fourth” (Upanishads the Principle Upanishads, 1953). It is described as a state

of consciousness that underlies waking, dreaming and sleeping.

An Integrated Model of States of Consciousness: The Junction Point Model

A junction point model has been proposed, an “ocean metaphor,” which conceptualizes

pure self-awareness as a fundamental state (an ocean), which sometimes appears as (a wave

of) waking consciousness, sometimes as dreaming consciousness, and sometimes as deep

sleep consciousness (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1972; Travis, 1994). In this model, pure

self-awareness underlies the activity of waking, dreaming and sleeping, and can be

objectively identified and subjectively experienced at the junction point between each state,

i.e., where waking has ceased and sleep has not yet begun. According to this model, the

activities of waking, sleeping, and dreaming are like currents that hide the silent nature of

pure self-awareness—the surface waves covering up the silent depths of the ocean of

consciousness. EEG research supports this model. Similar EEG patterns—theta/alpha

activity (6-10 Hz)—are seen during Transcendental Meditation practice, and during the

waking/sleeping junction, the sleeping/dreaming junction, and the dreaming/waking

junction (Travis, 1994).

11

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

One prediction of this model is that pure self-awareness is not only is an underlying

continuum, but that it can be integrated with waking, dreaming and sleeping. The next

section tests this prediction. It presents subjective and objective characteristics of the

integration of pure self-awareness with waking, dreaming and sleeping.

SECTION III:

INTEGRATION OF

PURE SELF-AWARENESS WITH

WAKING, DREAMING, AND SLEEPING

Repeated experience of the state of pure self-awareness alternated with customary

waking activity gives rise to a new integrated brain state in which pure self-awareness coexists with waking, dreaming and sleeping (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969; Travis et al.,

2002). In this new integrated state, pure awareness is experienced as a foundational state

that gives rise to ongoing experience (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969). It is analogous to the

vastness of the ocean that is not lost with each rising wave of daily life. Research has

identified physiological and phenomenological markers of this integrated state during sleep

and during problem solving.

Physiological Markers

Brainwave (EEG) and muscle tone (EMG) patterns during deep sleep

Mason and colleagues compared brain wave (EEG)S patterns and muscle tone (EMG)

during deep sleep—stage 3 and 4 sleep—in three groups of 11 subjects: non-meditating

subjects, meditating subjects not reporting this integrated experience, and meditating

subjects who reported the permanent integration of pure self-awareness with waking and

sleeping (Mason et al., 1997). Self-awareness during sleep is the critical test of the

integration of pure self-awareness with waking, dreaming, and sleeping, because it spans

12

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

the widest possible continuum of consciousness—from wide-awake, inner awareness to the

inertia of deep sleep.

The data were visually scored for sleep stages. Physiological patterns were analyzed

during Stages 3 and 4 of sleep, because these are the deepest stages of sleep, and so

represent a more stringent test of the experience of inner wakefulness during sleep.

The amount of delta activity in these three groups, which indexes depth of sleep

(Feinberg, 1999), was similar. All subjects appeared to have similar requirements for the

restorative value of sleep, which recent research suggests is for cellular repair following

normal day-to-day wear and tear on the brain (Huber et al., 2004).

These groups did, however, differ in the level of theta/alpha activity—6-10 Hz—

during sleep. During deep sleep, theta/alpha activity, characteristic of the experience of

pure self-awareness during Transcendental Meditation practice, increased with years TM

practice. Theta/alpha activity was lowest in the non-meditating subjects, medium in the

short-term meditating subjects, and highest in the subjects reporting pure self-awareness

during sleep. It is noteworthy that the subjective experience of the co-existence of pure

self-awareness and sleep was associated with the coexistence of the EEG patterns seen

during the experience of pure self-awareness and during sleep.

Muscle tone (EMG) levels decreased during slow wave sleep with years of TM

practice. They were highest in the non-TM group and lowest in the long-term TM group.

Reduced EMG during slow wave sleep has not been reported before. Future research is

needed to probe the significance of this observed physiological marker during sleep in

these subjects

EEG patterns during computer tasks

13

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Travis and colleagues (Travis et al., 2002) investigated EEG and ERP patterns in three

groups of individuals distinguished by their self-reported experience of the integration of

pure self-awareness with waking and sleeping. The three groups included: a Non-TM

group (N=17, age = 39.7±11.5 yrs),2 who did not practice a meditation technique and

rarely if ever reported the experience of pure self-referral consciousness; a Short-term TM

group (N= 17; age = 42.5±11.5 yrs), who had practiced TM for about eight years (7.8±3.0

yrs), and reported pure self-awareness during TM but only occasionally during daily life;

and a Long-term TM group (N=17; age = 46.5±7.0 yrs), who had practiced TM for about

25 years (24.5 ±1.2 yrs) and reported the continuous experience of pure self-awareness

throughout daily life. (Four of the subjects in the last group also participated in the earlier

sleep research.) The age differences between groups were not statistically significant,

F(2,48) = 1.90, p = .160) Each group comprised eight females and nine males. The

subjects were part of the larger Fairfield, Iowa community.

Subjects were in good health with no history of serious accidents, hospitalization, or

psychiatric diseases that would affect their EEG. They were free of prescription or nonprescription drugs. All subjects were right-handed by self-report. Informed consent was

obtained before the testing, and the University Institutional Review Board approved the

experimental protocol.

Table 1 represents these subjects’ demographics. As seen in this table, subjects in each

group spanned levels of education (high school to graduate training) and vocation. The

“Professions” category included architects, engineers, lawyers, researchers, computer

professionals, pharmacists, and university administrators and faculty. These were

2

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

14

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

combined into the “Professionals” category to simplify this table. These people were part

of the community. They had not been sequestered in an ashram.

Table 1. Education Levels and Vocation of the Subjects

Group

Non-TM

Education

2 High School

9 Some College

6 Graduate/Professional

Short-term TM

9 Some College

8 Graduate/Professional

Long-term TM

4 Some College

13 Graduate/Professional

Vocation

2 Artisans

2 Military

4 Business & Management

7 Professionals

2 Student

7 Business & Management

9 Professionals

1 Student

2 Artisans

4 Business & Management

11 Professionals

EEG patterns were recorded from all subjects during two paired-stimulus reaction time

tasks. Both tasks contained a pair of stimuli 1.5 seconds apart. We measured the rise in the

EEG baseline before the second stimuli. This is called the contingent negative variation

(CNV) (Walter, 1964). CNV amplitude 200 msec before the expected stimulus, called the

late CNV, reflects proactive preparatory processes, including mobilization of motor

(Brunia, 1993; van Boxtel et al., 1994) perceptual, cognitive, and attention resources

(Tecce et al., 1993).

The first task was a simple CNV task—asterisk/ tone/ button-press to stop the tone. The

second task was a choice CNV task—two numbers were sequentially presented 1.5 seconds

apart. Subjects responded with a left/right button press to indicate which number was

larger. Three brainwave measures calculated during the choice CNV trials distinguished

individuals who reported the integration of pure self-awareness with waking and sleeping.

These measures were (1) higher broadband frontal EEG coherence, (2) higher alpha and

15

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

lower gamma power, and (3) a better match of the timing and magnitude of CNV with task

demands.

Broadband (8-45 Hz) frontal coherence during tasks. Broadband frontal task EEG

coherence was highest in the Long-term group (Travis et al., 2002). The Non-TM group

had lowest task coherence, and the Short-Term group exhibited intermediate values of

coherence. The frontal cortices, which are reciprocally connected with nearly all other

cortical, subcortical, and brainstem structures (Fuster, 1993; Fuster, 2000), are important

circuits for emotion regulation (Davidson, 2002), moral reasoning (Moll et al., 2001; Moll

et al., 2002), decision making and planning (Fuster, 1993; Fuster, 2000), and self-concept

(Vogeley et al., 1999; Ben Shalom, 2000). Broadband coherence, in contrast to narrow

band coherence such as theta or alpha, may reflect large-scale cortical integration thought

necessary for the unity of subjective experience (Varela et al., 2001). Broadband frontal

coherence observed in subjects reporting this integrate state may characterize the largescale neural integration necessary to support the coexistence of pure self-awareness with

ongoing problem solving.

Increased alpha and decreased gamma power. The pattern of EEG power spectra during

tasks was also different between groups (Travis et al., 2002). The Long-term T group

exhibited higher alpha (8-10 Hz) EEG, which is associated with long-range, top-down

processes, and lower gamma (25-55 Hz) EEG, which is associated with local, bottom-up,

sensory processing (von Stein et al., 2000). Higher alpha and lower gamma EEG in Longterm TM subjects suggests that they process information differently: Inner, self-awareness

may play a greater role in cognitive processing.

16

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Different CNV patterns. The CNV patterns in the three groups support the proposition

that the Long-term subjects processed tasks differently. CNV in the Long-term group better

suited the task demands.

In the Long-term group, late CNV was higher during simple trials and lower during

choice trials. Thus, in the simple trials, Long-term TM subjects activated cortical response

circuits after the first stimulus because they what the correct response would be—a button

press. On the other hand, in the choice trials, Long-term TM subjects remained balanced

and did not activate cortical response circuits after the first stimulus because they did not

have enough information to determine a correct response. In contrast, the Non-TM

subjects exhibited the opposite response. They responded less during the easier simple

tasks, and more during the complex choice tasks. These responses, however, were not

appropriate. For instance, they activated response circuits before seeing the second number

in the choice task. They did not have enough information to make a correct response. This

is a more object-referral mode, reflecting overall task characteristics.

Frontal and central cortical areas participate in generating the CNV waveform (Tecce et

al., 1993). Appropriate timing of CNV activation suggests more appropriate timing of

frontal executive processes in the Long-term TM subjects. This CNV finding complements

the finding of higher levels of frontal EEG coherence during tasks in these subjects. Thus,

frontal areas, whose functioning are critical for generating levels of self-awareness

(Vogeley et al., 1999; Hobson et al., 2002) appear to function differently in these three

groups.

17

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

The inner experience of these subjects also markedly differed. The last section reports

results from an open-ended interview and paper-and-pencil tests of these three groups of

subjects.

Phenomenological Analysis of Interview Data

The three groups of subjects tested during the computer tasks were given an open ended

interview (Travis et al., 2004). Subjects were asked three questions. (1) “Please describe

experiences during the reaction time tasks;” (2) “Please describe experiences during sleep;”

and (3) “Please describe yourself.” Questions were always in that order. The first question

allowed the interview to gain rapport with the subjects. The second and third questions

were analyzed. During the interview, the interviewer asked the person to explain any

comment that did not seem obvious. For instance, when one person said: “I think I'm not

as happy as I used to be.” The interviewer asked: “You used to be ... does that mean two

years ago or 10 years ago?” Or the interviewer asked: “You talk about connectedness,

could you expand on that concept?” The interview ended when the person had no further

comments to make. These taped interviews were transcribed for later analysis.

Response to the Query: Please Describe Your Experiences during Sleep

During sleep, the non-TM group described typical sleep. For instance, one subject said:

Most times sleep is just that. I go to bed around 9:30 or 10:00 and put my head on

the pillow. It doesn't take me very long to fall asleep. I'm not aware of anything till

5 or 6 o'clock in the morning when it's time to get up.

Notice there is a gap in time between eyes-closed at night, and waking up in the morning.

This is a good night’s sleep.

The Long-Term TM subjects described an entirely different experience during sleep.

They described a continuum of self-awareness that was independent of time, space and

18

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

body sense, which was the ground for all experiences. One person described their

experience of falling sleep in terms of layers settling down:

When I go to bed at night, first layers of the body settle down. I notice when the

body is asleep. Lots of dreams come and go or just fatigue leaves the body, and then

5-6 hours later the body wakes up again in gradual layers and being aware of the

other side…hearing sounds and feeling the covers. First there’s no impulse to

attend to it, then I wake up.

Another person used the analogy of soda fizzing up and settling down to describe his

experience during sleep:

…there’s a continuum there. It's not like I go away and come back. It's a subtle

thing. It's not like I'm awake waiting for the body to wake-up or whatever… It's me

there. I don't feel like I'm lost in the experience. That's what I mean by a

continuum… you know its like the fizzing on top of a soda when you've poured it.

It's there and becomes active so there's something to identify with. When I'm

sleeping, it's like the fizzing goes down.

Response to the Query: Describe Your Self

These responses were analyzed using Atlas-ti software (Muhr, 2004). Atlas-ti is an

interactive software program designed for content analysis of interview data. In this

software, a section of transcribed text is opened in an Atlas-ti window. The experimenter

manually highlights phrases or sentences that contain a single idea. For instance, “I believe

anything is possible.” With a mouse click, the highlighted section is added to Atlas-ti’s

lists of “quotations” for that group. After going through the entire text, the experimenter

begins with the first quotation and generates a single word or phrase that encapsulates the

unit of meaning in that quotation. In Atlas-ti, these are called “codes.” The codes are

connected to the quotations in Atlas-ti so that double-clicking any code brings up all

quotations connected with it. These codes were not generated before hand, but were

generated from the data itself. This “grounded theory” approach (Sommer, 1991) was used

to discover inner experience of the integration of pure self-awareness with waking, sleeping

19

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

and dreaming, rather than test apriori hypotheses. Next the codes are structured into

hierarchical networks within subjects to create a picture of their inner world of meaning.

For instance, in the Non-TM group the networks centered on the descriptions (codes) of the

self as a (1) belief system, (2) cognitive style, (3) feelings, and (4) social roles. These

networks were then assigned a supercode. In the example of the Non-TM group, the

supercode was: “Self is identified with thoughts, feelings and actions.”

The responses to the question: “Describe yourself.” are summarized in Table 2. This

table reports average total words in each interview, average number of quotations selected

from each interview, total codes for each group and the resulting supercode. The total

codes are reported because the same code often summarized quotations from different

subjects in each group.

Table 2: Means and standard deviations of average number of words, quotations, total

codes and the supercode for each group from the content analysis.

Group

Average

Word

Count

Average

Quotations

Total

Codes

Non-TM

554±459

9.5 ± 5.0

57

Short-Term

850±760

9.3 ± 3.2

56

Long-term

1156 ±1180

10.1 ± 6.2

59

Supercodes

Self is identified with

thoughts, feelings, and

actions

Self is the director of

thoughts, feelings and

actions

Self is underlying and

independent of

thoughts, feelings and

actions

The interviews varied in number of words. However, this difference was not

statistically significant (F(2,48) = 2.07, p = .108) due to high variability within groups.

The average number of quotations and total codes were very similar between groups.

20

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

The super codes for the three groups are presented in Table 3, along with sample

quotations. This gives the reader a sense of the responses of subjects in each group that

generated the final super-codes.

Table 3. Results of Content Analysis: Super Codes and sample responses from the three

groups.

Group and

Sample Responses/Quotations

Super Code

N1: I guess I'm open to new experiences, and I tend to appreciate those things

Non-TM

Group:

that are different

Self is

N2: I kind of like to forge my own way

identified with N3: I am open to change and new ideas…I’m an adventuress. I like to go

thoughts,

out...and experiment with new ideas.

feelings, and

N4: I tend to appreciate those things that are different, even in my style of

actions

dress. I like something usually because its odd or strange or something that

other people absolutely wouldn't wear.

N5: I’m happy, caring, helpful, I like people who like to help other people; I

hate seeing anyone in trouble.

S1: I’m my own awareness. My ability to perceive and be aware. I’m my own

Short-Term

Group:

potential, my own power,

Self is the

S2: I’m my own capabilities; my ability to learn; my ability to do things…in

director of

it’s essential nature — my ability to act.

thoughts,

S3: There are many different levels to who I am. I'm a sister, a daughter, a

feelings, and

friend, an athlete, a nature lover, a seeker of the truth. I'm a very spiritual

actions

person. I believe that I can do and accomplish anything that I set my mind to.

S4: I am a little bit more silent, more reserved, and thoughtful than most, with

a deep desire to just succeed in all activities and at the same time to develop

spiritually very quickly.

S5: Who I am is who I am inside. How I think. What I believe. How I feel.

How I react.

L1: We ordinarily think my self as this age; this color of hair; these hobbies …

Long-term

Group:

my experience is that my Self is a lot larger than that. It’s immeasurably vast...

Self is

on a physical level. It is not just restricted to this physical environment.

independent of L2: It's the “I am-ness.” It's my Being. There's just a channel underneath that's

and underlying just underlying everything. It's my essence there and it just doesn't stop where I

thoughts,

stop…by “I,” I mean this 5 ft. 2 person that moves around here and there.

feelings, and

L3: I look out and see this beautiful divine Intelligence ...you could say in the

actions

sky, in the tree, but really being expressed through these things… and these are

my Self.

L3: I experience myself as being without edges or content…beyond the

universe…all-pervading, and being absolutely thrilled, absolutely delighted with

every motion that my body makes. With everything that my eyes see, my ears

hear, my nose smells. There's a delight in the sense that I am able to penetrate

that. My consciousness, my intelligence pervades everything I see, feel and

21

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

think.

L5: When I say "I" that's the Self. There's a quality that is so pervasive about

the Self that I'm quite sure that the “I” is the same “I” as everyone else's “I.”

Not in terms of what follows right after. I am tall, I am short, I am fat, I am this,

I am that. But the “I” part. The “I am” part is the same “I am” for you and me.

The super-codes derived from the content analysis delineated three quite different

descriptions of self-awareness in healthy adults. As seen in Table 3, the Non-TM group,

who rarely if ever reported the experience of pure self-awareness, described themselves

predominantly in terms of their thoughts, feelings and behavior: “I guess I’m open to new

experiences…” or “I tend to appreciate those things that are different…” or “I kind of like

to forge my own way.” This group described their sense-of-self as predominately

identified with their thoughts, feelings, and actions. Individuals in the Short-term group,

with infrequent experiences of pure self-awareness during daily life, described themselves

predominately as that which directed thoughts, feelings and actions. While their sense-ofself was less object-referral, it was still in terms of active processing. “I’m my awareness.

My ability to perceive and be aware.” or “I’m my own capabilities; my ability to learn.”

Individuals in the Long-term group, who reported the continuous experience of pure

self-awareness co-existing with waking and sleeping activity, described themselves as

underlying and independent of thoughts, feelings and actions. This group recognized

space-time boundaries. For instance, “And in certain contexts that has some value, like

when I tell my wife, I'm going to bed now.” However, they predominately described

themselves as existing outside of space-time causation—“my Self is immeasurably

vast…on a physical level;” “all-pervading;” “beyond speech;” or “My Self doesn’t stop

where I stop.”

22

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

The subjects described three very different inner states. Subjects in the Non-TM Group

described themselves in terms of their thoughts, feelings, and actions. In contrast, subjects

in the Long-term Group described themselves in terms of an independent, underlying

reality—a continuum that was outside time and space. To further explore the nature of the

inner experience of these subjects, they were administered standardized paper-and-pencil

instruments of personality and psychological measures.

Standardized Psychological Tests

After the above research, the subjects were re-contacted and were mailed four pencil-andpaper instruments measuring personality, inner/outer orientation, moral reasoning, and

anxiety. The mailing was followed up by phone calls to confirm receipt and participation.

Individuals returned their tests by mail in an enclosed self-addressed stamped envelope.

Personality. The International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) was used to measure

personality. The IPIP is the result of an international effort to develop and continually

refine a set of personality inventories, whose items are in the public domain, and whose

scales can be used for both scientific and commercial purposes. The IPIP items are freely

available on the Internet (http://ipip.ori.org/ipip/). This website also provides sub-scales

and their correlations with proprietary instruments such as the Minnesota Multiphasic

Personality Inventory or the California Personality Inventory.

We used 100 items in the IPIP that index the five personality constructs in the “Big

Five” model of personality: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional

stability, and openness to experience (Goldberg 1992). Extraversion represents the

tendency to be social, assertive and active, including the two dimensions of dominance and

sociability; Agreeableness is the tendency to be trusting, caring and gentle;

23

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Conscientiousness includes achievement and dependability; Emotional Stability includes

good emotional adjustment, high self-esteem, low anxiety, and high security and easiness

with others; and Openness to experience is the disposition to be imaginative,

nonconforming and unconventional (Judge et al., 2002; Judge et al., 2002). Consensus is

emerging that this five-factor model of personality may describe the most salient aspects of

personality (Goldberg, 1990).

Inner/Outer Orientation. Baruss developed this scale to quantify a subject’s worldview

along an outer/inner, material/transcendental dimension (Baruss et al., 1992). Subjects are

given 38 statements like: “My spiritual beliefs determine my approach to life.” Subjects

respond on a 7-point Likert Scale. This instrument has high item-total correlations (r = .56.62) and high Cronbach alpha coefficients (r = .82-.95) (Baruss et al., 1992). Scores on this

scale correlate highly with positive inner growth and meaningfulness of life (Baruss et al.,

1992). This scale yields a single number, which ranges from –114 (materialistic:

conceptualizing consciousness in terms of information processing) to +114 (transcendental:

emphasize subjective features of consciousness and declare it’s ontological primacy).

Moral Reasoning. Gibbs Socio-Moral Reflection Measure- Short Form (SMR-SF)

presents moral statements and asks subjects to describe why a moral act may be important

to them. For instance: “Keeping promises is important because...”; or “Helping one’s

friend is important because....” Gibbs has written an extensive reference manual to aid in

categorizing responses into moral maturity levels (Gibbs et al., 1992).

The SMR-SF can be group administered as a pencil-and-paper test, takes 15-20 minutes

to complete, and can be scored in 25 minutes. In addition, a scorer can gain competency in

25-30 hours of self-study. Gibbs’s SMR-SF has high test-retest reliability (r = .88), and

24

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

high Cronbach alpha coefficients (r = .92). Scores on the SMR-SF are highly correlated

with scores on Kohlberg’s Moral Judgment Interview (r = .70) (Gibbs et al., 1992), which

is much more intensive to administer and to score.

Levels of moral reasoning range from surface considerations to an inner autonomous

basis for decision-making. More abstract levels of moral reasoning emerge

developmentally and parallel growth in cognitive development and ego development

(Gibbs et al., 1992).

Anxiety levels. Spielberger’s State/Trait Anxiety (STAI) assesses both transitory

feelings of anxiety (state anxiety) and chronic feelings of anxiety (trait anxiety). In

epidemiological studies, 17% of adolescents (Wittchen et al., 1998) and 25% of adults

(Jacobi et al., 2004; Wittchen et al., 2005) report the occurrence of high anxiety in the past

12 months.

The tests of inner/outer orientation, state/trait anxiety, and personality were scored

using standard methods. Gibbs’s moral reasoning protocols were sent to trained scorers.

The scorers met the requirements for reliability in scoring, set forth in Appendix B and C in

Gibbs’s manual (Gibbs et al., 1992). Means, standard deviation, F statistics from

MANOVA and p-values of group differences are presented in table 4. P-values smaller

than .002 are bolded. As seen in this table, there were highly significant difference

between groups in inner/outer orientation, moral reasoning, anxiety, and emotional

stability.

Table 4. Means (standard deviations), F statistics and p-values for the psychological tests

25

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Test

Non-TM Short-Term Long-term

F stat

(2,26)

p value

9.03

.001

Inner/Outer Orientation

60.2(23.8)

70.0(12.4)

84.4(13.9)

Moral Reasoning

3.1(0.4)

3.4(0.4)

3.7(0.2)

5.69

.009

State Anxiety

35.9(15.2)

27.1(9.1)

22.3(2.4)

7.66

.002

Trait Anxiety

40.2(15.5)

30.6(7.6)

24.6(4.0)

7.90

.002

IPIP: Extraversion

3.1(0.6)

3.4(0.5)

4.1(0.8)

4.48

.021

IPIP: Agreeableness

4.0(0.5)

4.2(0.4)

4.6(0.4)

3.98

.031

IPIP: Conscientiousness

3.6(0.7)

3.9(0.8)

4.2(0.4)

2.28

ns

IPIP: Emotional Stability

3.3(1.0)

3.8(0.8)

4.4(0.4)

10.64

.0004

IPIP: Openness to Experience

4.0(0.4)

4.5(0.4)

4.7(0.4)

3.64

.040

A Pearson Correlation analysis showed that the psychological measures were highly

intercorrelated (all r > .5) A principle component analysis (PCA) was conducted to model

the variance in the test scores,. The first unrotated component of the PCA has long been

used in intelligence research as a measure of general intelligence or “g”—a construct

theorized to underlie performance across a range of reasoning and problem solving tests

(Spearman, 1904; Jensen, 1980). In the current study, the first principal component of the

unrotated PCA of psychological and personality tests may represent a general measure of

sense-of-self, a basic quality of self-consciousness or life-orientation, that is reflected in

these tests. Table 5 contains the factor loadings for the first and second unrotated

components, which accounted for 69% of the variance in test scores. The other

components had eigenvalues less than 1.

26

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Table 5: Variable Loadings of the 1st and 2nd Unrotated Components of the PCA

Inner/Outer Orientation

Moral Reasoning

State Anxiety

Trait Anxiety

Emotional Stability

1st Unrotated

Component

.71

.64

-.86

-.87

.88

2nd Unrotated

Component

-.48

-.30

.19

.12

-.11

Variance Accounted for

58%

12%

Variable

All variables from the psychological tests were converted to z-scores, weighted by

their factor loadings on the 1st unrotated component, and summed. This sum was called a

Consciousness Factor, because it was theorized to reflect a basic quality of consciousness

or life-orientation common to measures of personality and psychological health. An

ANOVA was used to test for main effects for group on the Consciousness Factor scores.

This analysis yielded significant main effects for group, F(2,26) = 13.2, p < .0001: NonTM: -4.78 ± 1.2; Short-Term: 0.40 ± 1.2; Long-term: 3.59 ± 1.1. Individual comparisons

revealed that Consciousness Factor scores for the Short-Term subjects were significantly

higher (two-tailed) than those of the Non-TM subjects (t(28) = 3.03, p = .006), and there

was a trend for Long-term subjects to be higher than those for the Short-Term subjects

(t(28) = 1.96, p = .062).

The Consciousness Factor, which represents a common dimension across several

tests of personality and psychological health, accounted for over half the variance among

groups. As “g” represents a common dimension among all intelligence tests (Spearman,

1904), so the Consciousness Factor may represent a common dimension among measures

of personality and psychological health. In light of the phenomenological data above,

27

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

higher scores on the Consciousness Factor may represent greater ‘de-embedding’ of senseof-self from mental processes and behavior.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The research reported here presents distinct subjective and objective characteristics of (1)

the experience of pure self-awareness during meditation practice and (2) the permanent

integration of pure self-awareness with waking, dreaming, and sleeping, a state called

enlightenment. This research includes investigation of meditation experience and objective

correlates of meditation effects on brain functioning after the practice. As advances in

instrumentation have enabled science to probe deeper into matter, so applying the

techniques developed by Eastern cultures—meditation practices—may enable science to

probe deeper into the individual psyche.

The first section discussed the possibility of a state of self-awareness free from customary

content of inner thoughts, feelings and outer perceptions. The second section reports

subjective descriptions and objective correlates of the experience of pure self-awareness

during TM practice. These findings suggest that underlying our turbulent, ever-changing

thoughts is a state that is not confined to our head, our heart or to the interior defined by

our body. Rather, pure self-awareness is described as being outside of time, space, and

body sense. It is a continuum of awareness that underlies all change. It is the deepest

aspect of our selves—called the Self. This section ended with a junction point model that

places pure self-awareness in relation to waking, sleeping and dreaming.

The Object-referral/self-referral continuum: From I to I

The range of concepts of self presented in the phenomenological analysis depict the

progressive de-embedding or detachment of self-awareness from its machinery to know the

28

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

world—the mind, senses and the body. This process of de-embedding from a more

expressed level to a more abstract level of self-awareness is the normal path of

development from childhood to adulthood. For instance, Piaget’s stages of cognitive

development can be understood as the progressive de-embedding of the center of one’s

sense-of-self from sensory, motor, and cognitive processes (Alexander et al., 1990). Thus,

one could have a behavioral-centered self in which the person identifies with sensorimotor

behavior: “I like to forge my own way;” or “I like to go out and experiment with new

ideas.” As one de-embeds from behavior, one could have a more cognitive-centered self in

which the person identifies with mental objects and ongoing thoughts and feelings: “I’m

open to new experiences.” In turn, one could become more affect-centered, in which one

identifies more with feelings and interrelations with others and the environment: “I care

deeply for other people;” or “I’m happy, caring, helpful. I like to help other people. This

progressive de-embedding of self-awareness from mental contents and processes is a

natural process that is shaped by ongoing experience (Alexander et al., 1990; Travis et al.,

2001).

The process of “de-embedding” is clearly seen in the interview results from these

subjects. Subjects in the Non-TM group described themselves predominantly in terms of

how they interacted with the world. That is, the self was “embedded” in or identified with

the processes by which they experienced the world. This could be characterized as an

object-referral style. One is what one does. Subjects in the Short-term group described

themselves as directing thinking and behavior—the first stages of the self “de-embedding”

or separating from the processes of thinking and behavior. “I’m my own capabilities; my

ability to learn.” And another: “I am my ability to perceive and be aware.” Yet, these

29

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

subjects still described themselves primarily in terms of what they did. In contrast, subjects

in the Long-term group described themselves as separate from what they were thinking or

doing—their identities, their selves were completely “de-embedded” from the processes of

thinking and behavior. “My Self is immeasurably vast... on a physical level. Not just

restricted to this physical environment.” And another: “It's my Being. There's just a

channel underneath that's just underlying everything. It's my essence there and it just

doesn't stop where I stop.” This style of functioning is a Self-referral style. In this state, the

Self has it’s own status. It is defined in terms of its own structure, independent of objects

and processes of knowing.

Self-awareness ranges from “I” to “I.” It ranges from the Self embedded and identified

with the processes of knowing to the Self aware of itself—from self to Self. While its

expression changes, it is the same fundamental value—pure self-awareness—expressing

itself differently depending on different styles of brain functioning. As experience

changes, so brain functioning changes. We begin to naturally appreciate who we are, and

appreciate our relation with the world around us.

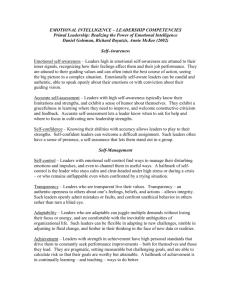

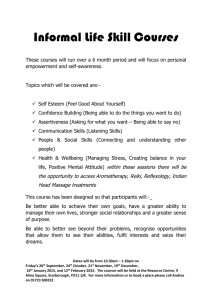

Figure 6 presents the proposed object-referral/self-referral continuum. The boxes at the

top and bottom of Fig. 6 present the ends of the proposed continuum. The three boxes on

the left side contain the supercodes that defined the three groups. The two boxes on the

right operationally define the ends of the continuum as defined by their Consciousness

Factor scores and the brain-based measures. As one de-embeds from cognitive and

behavioral process or moves towards the Self-referral end of this continuum, an integrated

set of mind/body measures appear: scores on the Consciousness factor increase, frontal

EEG 6-40 Hz coherence increases during tasks, alpha power increases and gamma power

30

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

decreases during tasks, and there is a better match between task demands and brain

preparatory responses as measured by contingent negative variation (CNV).

___________________

Insert Fig 6 about here

These subjective and objective findings may characterize the process of self “deembedding” from thinking, feeling and behavior. We suggest that this pattern of selfreport, performance on psychological tests and brain functioning represent the normal

range of human development, which is open to everyone born on earth, provided they gain

the necessary experiences to rise to the next level.

Movie Metaphor

This process of de-embedding can be understood in terms of a movie-metaphor.

Watching a movie, most individuals are “lost” in the movie. The movie is real. Emotions

and thoughts are dictated by the ever-changing sequence of the frames of the film. This is

an object-referral mode, where the objects of experience are salient and determine one’s

thoughts, feelings and sense-of-self. The meditative experience of transcending—the

repeated experience of pure self-awareness—alters this common movie-going experience.

Subjectively, the individual begins to “wake up” to his/her own inner status. Although

continuing to enjoy the movie, he/she gradually becomes aware that they exist independent

from the movie. They experience a value of ‘witnessing’ the activity around them. To

these individuals, the ever-changing movie frames are a secondary part of experience

because these frames are always changing. The most salient part of their every experience

is pure, self-awareness. What is ‘real’ shifts with time from the movie to self-awareness,

from the thoughts, feelings and actions to the Self, from object-referral to self-referral

awareness.

The reported experience of stable states of self-awareness de-embedded from, but coexisting with, the processes of waking, sleeping or dreaming has been called “Cosmic

31

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Consciousness” or “enlightenment” (Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1969; Shear et al., 1999).

This state has been described in many traditions (Bucke, 1991). Though many

scientifically minded people may consider enlightenment to be either imaginary,

impractical, or simply outside the boundaries of scientific investigation, the implications of

these data are that enlightenment may be operationalized by interviews, psychological tests,

and brain patterns during tasks and so brought into the arena of systematic scientific

investigation. As advances in technologies in modern science have expanded our

understanding of the outer environment, so applying subjective technologies from Eastern

traditions could expand our understanding of our inner world and help further our growth

along the proposed Object-referral/Self-referral continuum of Self.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, these phenomenological and physiological data suggest a range of

fundamentally different values of one’s identity or sense-of-self. On one end is the selfreferral experience in which the Self experiences itself through itself. This experience of

pure self-awareness is gained during practice the TM technique.

At the other end, the Self

is embedded in or identified with ongoing perception, thinking, and behavior. Future

longitudinal research can investigate the effect of different meditation and spiritual

traditions on moving individuals along this continuum. This line of research could

dramatically impact our understanding of the possible range of human development, and

could help promote a more unified understanding of spiritual development in terms of

development of brain integration.

32

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Object-Referral Mode

PREDOMINANCE OF COGNITIVE AND BEHAVIORAL

PROCESSES

“I like to forge my own way.”

Self identified with

thoughts and actions

Lower Consciousness Factor Scores

Lower moral reasoning

Lower happiness

Lower emotional stability

An Outer Orientation

Higher anxiety

Lower Integration Scale Scores

Higher frontal EEG coherence

Higher alpha/gamma power ratio

More efficient cortical

preparatory responses

Self as director of

thoughts and actions

Self is independent of

thoughts and actions

Higher Consciousness Factor

Scores

Higher moral reasoning

Higher happiness

Greater emotional stability

An Inner Orientation

Lower anxiety

Higher Integration Scale Scores

Higher frontal EEG coherence

Higher alpha/gamma power ratio

More efficient cortical

preparatory responses

Self-Referral Mode

Predominance of Self

“My self is immeasurably vast on a physical level.”

Figure 1: Schematic Representation of Sense-of-Self along an Object Referral/Self

Referral Continuum. The range of descriptions of sense-of-self extended from

Object-referral to Self-referral predominant modes. The three boxes on the left

present the supercode from the phenomenological, first person reports, and the two

right-most boxes present the psychological (Consciousness Factor scores) and

physiological (brain-based Integration Scale scores) correlates of the ends of the

proposed continuum.

33

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

REFERENCES

Alexander, C., J. Davies, C. A. Dixon, M. Dillbeck, S. Druker, R. M. Oetzel, J. M. Muehlman and D. OrmeJohnson (1990). Growth of Higher Stages of Consciousness: Maharishi Vedic Psychology of Human

Development. Higher Stages of Human Development. C. Alexander and E. Langer. New York,

Oxford University Press: 259-341.

Baars, B. (1997). In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind. New York, Oxford

University Press.

Badawi, K., R. K. Wallace, D. Orme-Johnson and A. M. Rouzere (1984). Electrophysiologic Characteristics

of Respiratory Suspension Periods Occurring During the Practice of the Transcendental Meditation

Program. Psychosomatic medicine. 46(3): 267-76.

Baruss, I. and R. J. Moore (1992). Measurement of Beliefs About Consciousness and Reality. Psychology

Reports 71: 59-64.

Ben Shalom, D. (2000). Developmental Depersonalization: The Prefrontal Cortex and Self- Functions in

Autism. Consciousness and Cognition 9: 457-60.

Brunia, C. H. M. (1993). Waiting in Readiness: Gating in Attention and Motor Preparation.

Psychophysiology 30: 327-339.

Bucke, R. M. (1991). Cosmic Consciousness. New York, E.P. Dutton.

Chung-Yuan, C. (1969). Original Teachings of Ch'an Buddhism. New York, Vintage Books.

Compton, W. C. and G. M. Becker (1983). Self-Actualizations and Experience with Zen Meditation: Is a

Learning Period Necessary for Meditation? Journal of clinical psychology. 39(6): 925-9.

Davidson, R. J. (2002). Anxiety and Affective Style: Role of Prefrontal Cortex and Amygdala. Biological

psychiatry. 51(1): 68-80.

Farrow, J. T. and J. R. Hebert (1982). Breath Suspension During the Transcendental Meditation Technique.

Psychosomatic medicine. 44(2): 133-53.

Feinberg, I. (1999). Delta Homeostasis, Stress, and Sleep Deprivation. Sleep 22: 1021-30.

Florian, G., C. Andrew and G. Pfurtscheller (1998). Do Changes in Coherence Always Reflect Changes in

Functional Coupling? Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 106(1): 87-91.

Fuster, J. M. (1993). Frontal Lobes. Current opinion in neurobiology. 3(2): 160-5.

Fuster, J. M. (2000). Executive Frontal Functions. Experimental brain research. Experimentelle

Hirnforschung. Experimentation cerebrale. 133(1): 66-70.

Gibbs, J. C., K. S. Basinger and D. Fuller (1992). Moral Maturity. Hillsdale, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An Alternative "Description of Personality": The Big-Five Factor Structure. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 1216-1229.

Gusnard, D. A., E. Akbudak, G. L. Shulman and M. E. Raichle (2001). Medial Prefrontal Cortex and SelfReferential Mental Activity: Relation to a Default Mode of Brain Function. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98(7): 4259-64.

Hebert, J. R., D. Lehmann, G. Tan, F. Travis and A. Arenander (in press). Enhanced Eeg Alpha TimeDomain Phase Synchrony During Transcendental Meditation: Implications for Cortical Integration

Theory. Signal Processing Journal.

Hobson, J. A. and E. F. Pace-Schott (2002). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Sleep: Neuronal Systems,

Consciousness and Learning. Nature Review of Neuroscience 3: 679-93.

Huber, R., M. F. Ghilardi, M. Massimini and G. Tononi (2004). Local Sleep and Learning. Nature 430(6995):

78-81.

Hycner, R. N. (1985). Some Guidelines for the Phenomenological Analyses of Interview Data. Human

Studies 8: 279-303.

Jacobi, F., H. U. Wittchen, C. Holting, M. Hofler, H. Pfister, N. Muller and R. Lieb (2004). Prevalence, CoMorbidity and Correlates of Mental Disorders in the General Population: Results from the German

Health Interview and Examination Survey (Ghs). Psychol Med 34(4): 597-611.

James, W. (1962). Psychology: Briefer Course. New York, Collier Books.

Jensen, A. R. (1980). Bias in Mental Testing. New York, The Free Press.

Judge, T. A., J. E. Bono, R. Ilies and M. W. Gerhardt (2002). Personality and Leadership: A Qualitative and

Quantitative Review. Journal of Applied Psychology 87(4): 765-780.

34

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Judge, T. A. and R. Ilies (2002). Relationship of Personality to Performance Motivation: A Meta-Analytic

Review. Journal of Applied Psychology 4(797-807).

Kelley, W. M., C. N. Macrae, C. L. Wyland, S. Caglar and S. Inati (2002). Finding the Self? An EventRelated Fmri Study. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 14(5): 785-94.

Kesterson, J. and N. F. Clinch (1989). Metabolic Rate, Respiratory Exchange Ratio, and Apneas During

Meditation. The American journal of physiology. 256(3) Pt 2: R632-8.

Kjaer, T. W., M. Nowak, K. W. Kjaer, A. R. Lou, H. C. Lou and D. K. G. D. John F Kennedy Institute

(2001). Precuneus-Prefrontal Activity During Awareness of Visual Verbal Stimuli. Consciousness

and cognition. 10(3): 356-65.

Lutz, A., L. L. Greischar, N. B. Rawlings, M. Ricard and R. J. Davidson (2004). Long-Term Meditators SelfInduce High-Amplitude Gamma Synchrony During Mental Practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

101(46): 16369-73.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1963). The Science of Being and the Art of Living. New York, Penguin.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1969). Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad Gita. New York, Penguin.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1972). The Science of Creative Intelligence. Livingston Manor, New York, Age of

Enlightenment Press.

Maltzman, I. (1977). Orienting in Classical Conditioning and Generalization of the Galvanic Skin Response

to Words: An Overview. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 106: 111-119.

Mason, L. I., C. N. Alexander, F. T. Travis, G. Marsh, D. W. Orme-Johnson, J. Gackenbach, D. C. Mason,

M. Rainforth and K. G. Walton (1997). Electrophysiological Correlates of Higher States of

Consciousness During Sleep in Long-Term Practitioners of the Transcendental Meditation Program.

Sleep. 20(2): 102-10.

Moll, J., R. de Oliveira-Souza, P. J. Eslinger, I. E. Bramati, J. Mouräao-Miranda, P. A. Andreiuolo and L.

Pessoa (2002). The Neural Correlates of Moral Sensitivity: A Functional Magnetic Resonance

Imaging Investigation of Basic and Moral Emotions. The Journal of neuroscience: the official

journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 22(7): 2730-6.

Moll, J., P. J. Eslinger and R. Oliveira-Souza (2001). Frontopolar and Anterior Temporal Cortex Activation

in a Moral Judgment Task: Preliminary Functional Mri Results in Normal Subjects. Arquivos de

neuro-psiquiatria. 59(3-B): 657-64.

Muhr, T. (2004). User's Manual for Atlas-Ti. Berlin, Scientific Software Development.

Natsoulas, T. (1997). Consciousness and Self-Awareness-Part I: Consciousness4, Consciousness5,

Consciousness6. Journal of Mind and Behavior 18: 53-74.

O'Gorman, J. G. (1979). The Orienting Reflex: Novelty or Significance Detector? Psychophysiology 16: 253262.

O'Shaughnessy, B. (1986). Consciousness. Midwest Studies in Philosophy 10: 49-62.

Pfurtscheller, G. (2001). Functional Brain Imaging Based on Erd/Ers. Vision research. 41(10-11).

Plum, F. and J. B. Posner (1980). The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma. Philadelphia, F.A. Davis.

Reps, P. (1955). Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. New York, Doubleday Anchor book.

Shear, J. and R. Jevning (1999). Pure Consciousness: Scientific Exploration of Meditation Techniques.

Journal of Consciousness Studies 6(2-3): 189-209.

Sokolov, E. N. (1963). Perception and the Conditioned Reflex. Oxford, Pergamon.

Sommer, B. (1991). A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research. New York, Oxford University Press.

Spearman, C. (1904). General Intelligence: Objectively Determined and Measured. American Journal of

Psychololy 15: 201-292.

Spinks, J. A., G. H. Blowers and D. T. L. Shek (1985). The Role of the Orienting Response in the

Anticipation of Information: A Skin Conductance Response Study. Psychophysiology 22: 385-394.

Taylor, J. G. (2001). The Central Role of the Parietal Lobes in Consciousness. Consciousness and cognition.

10(3): 379-417.

Tecce, J. J. and L. Cattanach (1993). Contingent Negative Variation (Cnv). Electroencephalography: Basic

Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. E. Neidermeyer and L. d. Silva. Baltimore,

Williams & Wilkins: 887-910.

Travis, F. (1994). The Junction Point Model: A Field Model of Waking, Sleeping, and Dreaming Relating

Dream Witnessing, the Waking/Sleeping Transition, and Transcendental Meditation in Terms of a

Common Psychophysiologic State. Dreaming 4(2): 91-104.

35

Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum

Travis, F. and A. Arenander (in review). Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study of Effects of Transcendental

Meditation Practice on Interhemispheric Frontal Asymmetry and Frontal Coherence. International

journal of neuroscience.

Travis, F. and C. Pearson (2000). Pure Consciousness: Distinct Phenomenological and Physiological

Correlates of "Consciousness Itself". The International journal of neuroscience. 100(1-4).

Travis, F., J. J. Tecce and C. Durchholz (2001). Cortical Plasticity, Cnv, and Transcendent Experiences:

Replication with Subjects Reporting Permanent Transcendental Experiences. Psychophysiology 38:

S95.

Travis, F. and R. K. Wallace (1997). Autonomic Patterns During Respiratory Suspensions: Possible Markers

of Transcendental Consciousness. Psychophysiology. 34(1): 39-46.

Travis, F. and R. K. Wallace (1999). Autonomic and Eeg Patterns During Eyes-Closed Rest and

Transcendental Meditation (Tm) Practice: The Basis for a Neural Model of Tm Practice.

Consciousness and cognition. 8(3): 302-18.

Travis, F. T., A. T. Arenander and D. DuBois (2004). Psychological and Physiological Characteristics of a

Proposed Object-Referral/Self-Referral Continuum of Self-Awareness. Consciousness and

Cognition. 13: 401-420.

Travis, F. T., J. Tecce, A. Arenander and R. K. Wallace (2002). Patterns of Eeg Coherence, Power, and

Contingent Negative Variation Characterize the Integration of Transcendental and Waking States.

Biological psychology. 61: 293-319.

Upanishads the Principle Upanishads (1953). London, Allen and Unwin.

van Boxtel, G. J. and C. H. Brunia (1994). Motor and Non-Motor Aspects of Slow Brain Potentials.

Biological psychology 38: 37-51.

Varela, F., J.-P. Lachaux, E. Rodriguez and J. Martinerie (2001). The Brainweb: Phase Synchonization and

Large-Scale Integration. Neuroscience 2: 220-230.

Vogeley, K., M. Kurthen, P. Falkai and W. Maier (1999). Essential Functions of the Human Self Model Are

Implemented in the Prefrontal Cortex. Consciousness and cognition. 8(3): 343-63.

von Stein, A. and J. Sarnthein (2000). Different Frequenices for Different Scales of Cortical Integration:

From Local Gamma to Long Rnage Alpha/Theta Synchronization. International Journal of

Psychophysiology 38: 301-313.

Walter, W. G., Cooper, R., Aldridge, V.J., McCallum, W.C., Winter, A. L. (1964). Contingent Negative

Variation. An Electric Sign of Sensorimotor Association and Expectancy in the Human Brain.

Nature 203: 380-384.

Wittchen, H. U. and F. Jacobi (2005). Size and Burden of Mental Disorders in Europe-a Critical Review and

Appraisal of 27 Studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.

Wittchen, H. U., C. B. Nelson and G. Lachner (1998). Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Psychosocial

Impairments in Adolescents and Young Adults. Psychol Med 28(1): 109-26.

Woodruff-Smith, D. (1986). The Structure of (Self-)Consciousness. Topoi 5: 149-156.

Wundt, W. (1897). Outlines of Psychology. Leipzig, G.E. Stechert.

36