The General Election Campaign Steven E. Schier and Janet Box

advertisement

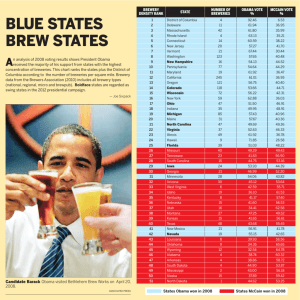

The General Election Campaign Steven E. Schier and Janet Box-Steffensmeier Once it became clear that Barack Obama and John McCain would be the major parties’ presidential nominees, many imposing questions surrounded the fall general election contest. Would race prove an impediment for Barack Obama, the first African American nominee of a major party in the nation’s history? Would the impressive financial advantage his campaign had accrued prove decisive in the fall contest? Could John McCain overcome the unpopularity of his party and its president? How would candidate debates and campaign events affect the 2008 election outcome? Would the vice presidential nominees affect the election result? Our account relates the 2008 fall campaign’s answers to these questions. Underlying such uncertainties, however, lay certain conditions that pointed to a Democratic victory in November. Political scientists produced many models aimed at predicting the presidential election outcome. By the second half of 2008, virtually all of these models forecast a Democratic victory in November.1 In eight different prediction models, the most common variables used to estimate the election outcome were economic conditions and the job approval of the incumbent president. Both of these influences pointed in the same direction. Declining economic growth, rising unemployment and the remarkably low job approval of President George W. Bush all foretold good news for Democrats and bad tidings for the GOP, regardless of campaign events in the fall. Since the creation of public opinion polling, whenever a retiring president had a job approval below 45 percent, his party’s nominee lost the White House. Bush’s approval rating ranked well below that throughout 2008, frequently dipping below 30 percent. 1 A sluggish economy contributed to Bush’s low approval, but the unpopular war in Iraq also served to depress GOP prospects. Though progress in the war had accelerated markedly because of a U.S. troop surge in 2007, a majority of the American public continued to view the initiation of the war by the Bush administration in 2003 as a mistake. Just as the party presiding over a poor economy suffers in presidential elections, so also have the “war parties” in American history. David Mayhew notes that a war can bring electoral contests about whether it “should have been fought in the first place” and over the possibility of “incompetent management” (Mayhew 2005, 480). Both matters plagued the GOP in 2008. Larry Bartels and John Zaller also found that the drawn-out wars of Korea and Vietnam cost the party in charge a 4 percent loss at the polls in the 1952 and 1968 elections as the wars dragged on (Bartels and Zaller 2001). The Iraq war’s 2006 electoral costs for the GOP, when it lost control of both the Senate and House, placed it firmly in the Korea/Vietnam category. 2008 promised more of the same. A number of other circumstances also favored Democrats in the 2008 presidential race. John McCain sought to succeed a two-term incumbent of his party, a feat accomplished only once since 1932. A historically high proportion of Americans – in some polls as high as 90 percent – though the nation was on the “wrong track.” Polls reported that far fewer Republicans indicated enthusiasm for their nominee than did Democrats for their nominee. Surveys also indicated that the percentage of adult Americans calling themselves Republicans, which had reached parity with Democrats at 37 percent in the 2004 election, was now slumping considerably and falling five to ten points behind that of their partisan rivals. Almost two dozen House Republicans had retired rather than face reelection in such a situation (York 2008). The adverse environment for Republicans was reflected in the fundraising totals for the parties’ presidential candidates in 2008. During the primary season, Democratic presidential 2 candidates vastly outraised Republicans by $787 million to $477 million. Barack Obama led the Democratic pack during the primaries with an astounding $414 million raised, about twice that of McCain’s $216 million. Hillary Clinton’s withdrawal from the presidential race in June had cleared the way for the Obama campaign to focus on the convention and fall campaign. The campaign chose to opt out of the public financing system, foregoing $85.1 million in public general election funds to be able to raise unlimited cash from individual contributors, albeit in amounts no larger than $2,300 per person. This decision would prove to be wise, allowing the Obama campaign to raise an unprecedented $764.8 million during the 2008 election cycle. With abundant funds, they would blanket the airwaves with ads and create a get-out-the-vote ground game in key states that the GOP could not rival. Flush with cash, the Obama campaign decided to “expand the field” of the race by establishing dozens of campaign offices not only in crucial swing states like Florida, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio and Pennsylvania, but also in traditionally GOP strongholds like Indiana, North Carolina, Colorado, and Virginia. Though the GOP retained a formidable get out the vote operation developed in 2004 for 2008, the McCain campaign and national party simply did not have the resources to match the extensive network of field offices created by Obama’s millions. No modern general election campaign had ever assembled the funds and expertise to create such an extensive ground game before. Whatever the events of the fall campaign, a substantial Obama advantage in cash and organization would persist through the autumn. Given all this, it was no surprise that the Democratic nominee enjoyed a lead in the polls over the GOP candidate throughout 2008. Figure 1 shows the pattern of the McCain-Obama horserace over time. With few exceptions in 2007-2008, Obama was ahead, a trend that would persist through the general election campaign, except for a brief McCain lead in mid-September. 3 But in August 2008 Obama’s lead was usually within single digits, and he was a newcomer to presidential politics with some vulnerabilities as a candidate. Previous prediction models had not always foretold the winner; many of them had favored Al Gore in 2000. That suggested that the race might well go either way, depending upon the events of the fall. Neither campaign could take its situation for granted; each faced challenges. [Figure 1 about here] Campaign Strategies during the Convention Season Another uncertainty regarding the general election involved the impact of the party conventions on the presidential race. Traditionally, the “out” party held its convention first, about a month before the convention of the incumbent party. In 2008, that schedule was truncated. Democrats moved their convention to the end of August, one week before the GOP convention of early September. One reason for this move was to avoid possible post convention difficulties like those suffered by John Kerry in 2004 when advertising by the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth had damaged his candidacy. Such tight scheduling, however, might also limit Obama’s post convention “bounce” in the polls. How would back-to-back conventions change the race? Traditionally the post convention “bounce” produced an improvement in a nominee’s competitive standing from the low to high single digits. Would that prove to be the case this time? Both parties located their convention in swing states they hope to win in the fall – the Democrats in Colorado and the Republicans in Minnesota. During the summer, the Obama campaign has conducted extensive polling on the strengths and weaknesses of the two parties’ nominees. They fixed on a strategy that would prove quite productive in the months ahead: tie McCain as closely as possible to the unpopular Bush. David Axelrod, the campaign’s chief strategist, in articulating this approach, held that 4 America was looking for “the remedy, not the replica” (Lizza 2008). This approach involved distinguishing Obama from “Washington insiders,” as he had done with great success in his contest with Hillary Clinton during the primaries. Further, Obama’s research revealed that voters did not know that much about John McCain. Joel Benenson, the campaign’s pollster, recalled, “What we knew at the start of the campaign was that the notion of John McCain as a change agent and independent voice didn’t exist anywhere outside of the beltway.” (Lizza 2008). The adverse environment for the GOP, limited voter knowledge about John McCain and large financial advantage made the execution of a fall campaign straightforward for the Obama high command. But some immediate challenges lay before them. They had to prevent party disunity at the national convention, introduce their candidate effectively to the public via his convention speech, and pick a vice presidential nominee who would offset and shortcomings of Obama as a candidate. To allay concerns about his inexperience, Obama chose Joe Biden, a thirty-six year veteran of the U.S. Senate and chair of its important Foreign Relations committee, as his vice presidential nominee. Biden was to prove a jaunty campaigner, but one whose propensity for verbal missteps would produce difficulties for the campaign throughout the fall. The convention itself began a bit listlessly, but delegates were roused by endorsement speeches by Hillary and Bill Clinton. Biden’s speech featured sharp attacks on partisan rivals, a usual task left to the vice presidential nominee. Referring to McCain, his longtime friend, he asserted, “John thinks that during the Bush years ‘we've made great progress economically.’ I think it's been abysmal. And in the Senate, John sided with President Bush 95 percent of the time.” That fact would become a familiar trope in the Democratic campaign speeches and advertisements. Obama’s well-delivered speech provided a vast spectacle, filling a football stadium with thousands of fans and drawing almost forty million television viewers. His 5 remarks concluded with a call for change and unity, major themes of his candidacy throughout 2008: The men and women who serve in our battlefields may be Democrats and Republicans and Independents, but they have fought together and bled together and some died together under the same proud flag. They have not served a Red America or a Blue America - they have served the United States of America. . . . At defining moments like this one, the change we need doesn't come from Washington. Change comes to Washington. Change happens because the American people demand it - because they rise up and insist on new ideas and new leadership, a new politics for a new time. Political scientist James Stimson estimated Obama’s post convention poll bounce six days after Obama’s speech at 4.33 percent, a bit under the historic average of 4.9 percent (Stimson, 2008). One reason for the small bounce was probably the surprising announcement of Sarah Palin, Governor of Alaska, as John McCain’s running mate on the morning after Obama’s speech, depriving the Democratic nominee of several days of positive post convention coverage. Palin had served less than two years as governor and before that had been mayor of the small town of Wasilla, Alaska. The choice surprised the Obama campaign and the rest of the political world. Few knew what to expect from her. The Palin pick was one of several attempts by the McCain to “shake up” the adverse environment of the race. The McCain campaign during the summer had puttered slowly along, short on funds and receiving less media attention than did the Obama effort. Top McCain aides understood they faced a challenging situation. Unlike the Obama campaign, which could readily execute a simple strategy and message that was likely to bring electoral success, the McCain strategists faced a much more difficult challenge. Chief strategist Steve Schmidt recalled: “This was a 6 campaign that was dealt a very, very tough hand of cards. It was highly unlikely that there will ever be another campaign in our lifetimes that [will feature] a worse environment than the environment that John McCain had to run in” (Schmidt 2008). Since no simple message would work, the McCain campaign focused instead on a series of tactical disruptions that might thrown their opponent off track and open up new opportunities for them. The main opportunities for surprises that might change the race lay in the central events of the fall campaign: the vice presidential pick, the convention acceptance speeches, and the candidate debates. The McCain campaign began their disruptions with a “celebrity” ad in the summer, which mocked Obama’s July international trip by comparing him to Paris Hilton and Brittany Spears. The celebrity label disturbed the Obama campaign, which viewed it as a negative description that might stick to their candidate. Then came the Palin pick, which caught Obama campaign off guard. Palin had been Schmidt’s recommendation in order to shake up the race. A governor with a reputation as a reformer, she gained McCain’s nod after a few conversations. The immediate public reaction to Palin was positive, augmented by her impressive acceptance speech at the GOP convention. Her speech both introduced her to the public and included some barbs regarding Obama’s inexperience. Describing herself as a “hockey mom”, she ad libbed the following description: “You know the difference between a pit bull and a hockey mom? Lipstick.” She contrasted her experience with local government to that of Obama’s as a community organizer: “Before I became governor of the great state of Alaska, I was mayor of my hometown. And since our opponents in this presidential election seem to look down on that experience, let me explain to them what the job involves. I guess a small-town mayor is sort of like a ‘community organizer,’ except that you have actual responsibilities.” Palin’s strongly conservative positions created enthusiasm among GOP activists, who had been 7 cool to McCain since he clinched the nomination in the spring. McCain’s speech was reasonably well delivered, but proved no match for the Palin and Obama rhetorical successes of the convention season. He concluded it by referring to his career fighting for reform: “Fight with me. Fight with me. . . . Nothing is inevitable here. We're Americans, and we never give up. We never quit. We never hide from history. We make history.” By the end of the GOP convention, however, the McCain tactical disruption seemed to have worked. The GOP ticket enjoyed a convention bounce estimated by James Stimson at eight points, doubling that of the Democratic ticket. By September 8, four days after the end of the GOP convention the average of national polls put McCain ahead of Obama by three points. A Series of Unfortunate Events The McCain lead would quickly dissipate due to a unique combination of events. Some were expected, such as the inevitable decay of the convention bounce. Some were self-inflicted, such as a series of McCain campaign miscues, including Palin’s poor media “rollout” and McCain’s abrupt behavior during the nation’s financial crisis. That crisis was truly an unprecedented event. It was not just unique in 2008, but had never before occurred in the midst of any general election campaign in American history. The international financial system faced a dramatic threat to its stability of the sort it had never encountered in the decades since it had effectively globalized. Before these tumultuous events transformed the presidential race, the McCain campaign ran into trouble. Though Sarah Palin’s nomination had garnered much attention and interest in the GOP ticket – the television ratings for the GOP convention matched that of the Democratic convention – she had no experience with presidential politics and very limited knowledge of international affairs. The McCain campaign then made a series of mistakes in addressing these 8 shortcomings. In the weeks following the convention, she avoided press conferences and only spoke at campaign rallies. She was limited to two high profile media interviews, first by ABC anchor Charles Gibson and later by CBS anchor Katie Couric. Palin was cautious during the Gibson interview and did not display an abundant understanding of global issues. Her comment that her international experience came from Alaska being on the Russian border received widespread derision. But the Couric interview was worse for Palin. Reportedly, she objected to the invasive staff role during her preparation for the Gibson interview, and did not prepare extensively for Couric. Her lack of knowledge received embarrassing exposure when she could not name a Supreme Court decision with which she disagreed, and could not discuss McCain’s record as a governmental reformer in any detail. This led to harsh but funny depictions of her by actress Tina Fey on Saturday Night Live and a steady decline in the number of American indicating in polls that they considered her a qualified to run for vice president or that they had a positive opinion of her as a candidate. Later in the campaign, Palin gave many more media interviews and press conferences without incident, drawing into question the McCain media strategy for her in September. In retrospect, it seemed a serious stumble by a campaign that could afford few miscues. Joe Biden also earned derisive treatment on Saturday Night Live for his verbal gaffes during the campaign – such as his description of FDR addressing the American people on television in the 1930s, long before television arrived in American homes – but polls consistently indicated that a majority of respondents viewed him as qualified to be president. Though Palin performed soundly in the vice presidential debate on October 2, surveys all revealed that the public through Biden had won. Palin continued to outdraw McCain during her campaign 9 appearances and she remained a strong favorite among Republicans. Over the course of the campaign, however, independents, moderates and suburbanites – crucial groups of swing voters – steadily viewed her more negatively. By Election Day, she was not the unambiguous positive for the McCain campaign she seemed to be at the GOP convention. Sarah Palin made history, though, by becoming a major player in the campaign overnight and the first female GOP vice presidential nominee. The big blow of history came in the global financial crisis of September 2008, the largest such crisis in seventy years and the first occurring in the midst of a presidential general election campaign. The crisis originated in the housing market, where the federal government for years had encouraged high-risk “subprime” mortgages. Packages of these mortgages had been “securitized,” made into investment vehicles, offered to investors by financial institutions. At the time, it was widely thought that securitization would make the issuance of such risky mortgages less of a gamble. By 2008, it was clear that this was not the case. A U.S. monetary policy pursued by the Federal Reserve Board had made the cost of credit negligible for several years prior to 2008. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), federally created corporations that underwrote mortgages, had engaged in risky mortgages for years, assuming that the creation of mortgagebacked securities would shield them from losses. As the housing market slumped in 2007-2008, mortgage-backed securities and the financial condition of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac became parlous. This led to a collapse of several major American financial institutions in September 2008, a crisis threatening the very operation of the international financial system. On September 7, the federal government took control of the operations of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, accepting responsibility for their swollen liability of some $5 trillion in 10 mortgages. Then on September 15 came the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers investment house, a Wall Street titan, brought on in part by its holding of suspect mortgage-backed securities. The reaction of American and international stock markets was severe; the very confidence of global financial securities seemed in question. The next day, the federal government announced a $5 billion emergency loan to rescue the stressed American International Group investment company in order to prevent a further collapse of international financial markets. Two days later, the Bush administration announced a $700 billion plan for the government to buy mortgage-backed securities in order to inject funds to the finance companies that had overinvested in them. This, it was hoped, would restore confidence in these companies and, in turn stabilize the national and international financial systems. That plan required Congressional approval. It is at this point the presidential politics directly intersected with the crisis. Though the economy was the foremost public concern throughout 2008, the crisis boosted its mention as the most important problem to the highest level since the 1980 recession (Jones 2008). It became the preeminent issue in fall 2008 as gas prices and the Iraq war fell as public concerns. In this situation, each presidential candidate faced a challenge. McCain, who previously had admitted his limited understanding of economics, needed to demonstrate a reliable competence in addressing the issue. Obama, a relative newcomer to national politics, had to respond in a way that instilled confidence in his ability to be president. McCain stumbled at the outset of the crisis by claiming in a speech “the fundamentals of our economy are sound” when world financial markets were teetering. His campaign’s penchant for seeking tactical advantage also led him to undertake audacious actions. On Wednesday, September 24, McCain agreed, upon Obama’s initiative, to sign a joint statement of principles about how to address the crisis. Immediately 11 after agreeing to this in a phone call, however, McCain suspended his campaign, urged cancellation of the first presidential debate because of the crisis, and flew to Washington. All of these actions were a surprise to Obama, who responded by urging that the debate go on as scheduled because, “It’s going to be part of the president’s job to be able to deal with more than one thing at once.” McCain’s rush back to Washington did not go well for him. At a White House meeting both he and Obama attended the next day, it was clear that bipartisan consensus on the bailout plan did not exist. House Republicans did not agree with its provisions. McCain urged that their perspectives be heeded in the bailout negotiations, but the candidate himself never became a major participant in deliberations over the bailout package. Meanwhile, he quickly dropped his objection to the first debate and flew to Jackson, Mississippi to participate, despite the fact that the crisis was no closer to resolution. Three days later, on Monday, September 29, House Republicans voted in large numbers to insure the failure of the bailout plan on the House floor. This triggered a big downturn in stocks around the globe, and more frenzied negotiations. A revised plan passed on Friday, October 2 and was quickly signed into law. Both Obama and McCain voted for the bailout plan. Stocks, however, remained depressed throughout the remainder of the campaign season, and a parade of bad news regarding rising unemployment and negative economic growth arrived in September and October. The Obama campaign had hoped that McCain’s actions would label him as unstable and erratic in a crisis, and polls indicated that public views of McCain’s leadership abilities declined with the financial crisis. Obama, who was generally constructive during the crisis, urging fellow Democrats to support the rescue plan, saw his leadership scores improve. The greater problem of the crisis for McCain, however, was the very presence of the economic problems themselves. 12 The economic issue had benefitted the Democrats all year and recent events had made those issues dominant for the remainder of the campaign. Polls indicated considerable public opposition to the bailout plan itself. By suspending his campaign and rushing to Washington, McCain had managed to associate himself strongly with both with a serious problem, the financial crisis, and the controversial solution to it. Obama, whose reaction to the October economic events was less impetuous, suffered less from the crisis and now had a powerful economic issue buoying his “change” message. McCain’s tactical gamble did not pay off. The Debates Presidential debates are one of the major “flex points” in the general election season because they directly expose the candidates in verbal competition before millions of Americans. Such situations create mass opinions, giving both campaigns a rare opportunity to reset the race. The McCain campaign hoped to illustrate through the debates that Obama was not up to the job of president; that he was dangerously inexperienced. The Obama campaign sought demonstrate their candidate’s presidential readiness and to tie McCain closely to the unpopular George W. Bush. The first debate, on September 26, involved foreign policy and featured the two candidates at rival lecterns. The vice presidential debate on October 2 featured an identical podium format, and was not limited to a particular subject. The second presidential debate On October 7 presented the candidates in a town hall format, ambling about and answering audience questions. The final, October 15 debate placed the candidates at a table with a single moderator, answering questions and engaging in direct dialogue over economic issues. Polls and most audience surveys of the debates indicated that the Democratic candidate won every debate. Partisans predictably labeled their party’s candidate the winner, but, importantly, independents consistently viewed the Democrat as winning the debate as well. Perhaps the circumstances 13 surrounding the election – an unpopular president, a slumping economy, an unpopular war in Iraq – stacked the deck prohibitively against a successful Republican debate performance. Or perhaps Obama and Biden were just better debaters than McCain and Palin. The debates did not involve any memorable “gotcha” moments that changed the course of the campaign. Such events are rare in the history of general election debates. Obama, for his part, succeeded in appearing presidential and allaying doubts about his leadership ability. His rhetoric placed him in the mainstream on many issues. One of his most successful moments, measured by audience reaction, came at the end of the third debate, when he stressed personal responsibility in education: “But there's one last ingredient that I just want to mention, and that's parents. We can't do it just in the schools. Parents are going to have to show more responsibility. They've got to turn off the TV set, put away the video games, and, finally, start instilling that thirst for knowledge that our students need” (Sullivan 2008). He repeatedly linked McCain to the unpopular George W. Bush, not only during the debates, but also in many of his campaign ads that were flooding the airwaves at this time. McCain in the first debate asserted that Obama’s willingness to meet with hostile foreign leaders “without preconditions” amounted to dangerous diplomacy. That failed to move voter sentiment, as did his mention in the final debate of Obama’s past association with 1960s radical William Ayers. He did present another criticism during the final debate that proved more useful to his campaign. McCain introduced an individual who would figure prominently in the campaign’s final weeks: “Joe the Plumber,” specifically Samuel Joseph Wurzelbacher, a plumber’s assistant from Holland, Ohio. Wurzelbacher was captured on tape raising concerns with Obama about his campaign’s proposal to raise taxes on those making more than $250,000 a year. Obama in response said: "It's not that I want to punish your success. I just want to make 14 sure that everybody who is behind you, that they've got a chance for success, too . . . When you spread the wealth around, it's good for everybody." Citing the incident, McCain challenged Obama: “You were going to put him in a higher tax bracket which was going to increase his taxes, which was going to cause him not to be able to employ people, which Joe was trying to realize the American dream [sic].” The Endgame By the end of the debates, on October 20, Obama enjoyed an average lead of six points in national polls. The Obama strategy of reassurance had worked. The economy, in desperate straits, remained central to voters’ minds. His campaign’s impressive ground game was outstripping GOP efforts in all major states and his superior campaign funding allowed him to outspend McCain on the airwaves by considerable margins as well. Under the harsh scrutiny of the campaign media, Obama had not made any major mistakes. McCain’s attempts to make Obama appear to be the “dangerous” choice had not succeeded, and his own judgment was now called into question regarding his actions during the September financial crisis and his choice of Sarah Palin as a running mate. The McCain campaign, however, had found two tactical opportunities to employ in the final stage of the campaign. Obama’s “spread the wealth around” became an opportunity to revive worries about possible tax increases. Joe the Plumber himself joined the campaign trail for McCain. The campaign expanded the critique to suggest that Obama was a sort of socialist. Sarah Palin, on the stump two days after the final debate, claimed: “Senator Obama said he wants to quote ‘spread the wealth.’ . . . Friends, now is no time to experiment with socialism. . . . Whatever you call his tax plan and that redistribution of wealth, it will destroy jobs. It will hurt our economy.” Another tactical opportunity came in the form of a statement by Biden recorded 15 at a Democratic fundraiser: “Mark my words. Mark my words. It will not be six months before the world tests Barack Obama . . . The world is looking. . . . Watch, we're gonna have an international crisis, a generated crisis, to test the mettle of this guy.” The McCain campaign jumped on this to claim that Obama was in fact a risky choice, a person whom could not be trusted to keep American secure. The Obama campaign, for its part, was able to rely on arguments at the end that had worked for them throughout the fall campaign. On October 26, Obama claimed that McCain’s recent criticisms of President Bush, aimed at distancing himself from the president, were “like Robin getting mad at Batman.” The Obama campaign’s unprecedented funds allowed them to purchase a half-hour for a primetime program on several national networks on the Wednesday before the election. Most of the program concerned the economic problems of voters in a number of swing states such as Missouri, New Mexico, Ohio, with the candidate explaining how his policies would improve their situations. He explained his policy specifics while expressing empathy: “We measure the strength of our economy not by the number of billionaires we have or the profits of the Fortune 500, or by whether someone with a good idea can take a risk and start a new business, or whether the waitress who lives on tips can take a day off and look after a sick kid without losing her job.” McCain, for his part, had to appear on interview shows to get some rival exposure. During the final weeks, the McCain campaign increased its ad buys to match those of Obama, after being badly outspent for months. In the last days of the campaign, McCain and Palin hurriedly visited many states that previously had been safely Republican – Indiana, Missouri, North Carolina and Virginia – while also traveling to traditional swing states like Ohio, Florida 16 and Pennsylvania. The travel schedule revealed, far more than any candidate’s rhetoric, that the GOP ticket‘s prospects were dimming. The Election Result Election night delivered a solid victory for the Democratic ticket in both the popular vote and the Electoral College. Obama and Biden garnered 52.9 percent of the popular vote and 365 electoral votes to the GOP ticket’s 45.7 percent and 173 electoral votes. A Democratic ticket had gained 50 percent of the popular vote for the first time since 1976. Turnout was estimated at about 131.3 million, constituting between 61.6 and 63.0 percent of eligible voters, depending on varying estimates of the total eligible electorate. That comprised the highest turnout since the 1960s, a testament to Obama’s massive field organization. Even so, it was only slightly higher than 2004’s 59.6 percent turnout (Center for the Study of the American Electorate 2008; McDonald 2008). Figure 2 reveals that nine states voting for the GOP in 2004 went Democratic. In several of these states, as evident in Table 1, the swing to the Democrats was pronounced. Comfortable 2004 GOP victories in North Carolina, Virginia and Florida were transformed to narrow Democratic wins. Narrow 2004 GOP wins in Iowa, Nevada, New Mexico and Colorado became lopsided defeats in 2008. Ohio, traditionally a swing state in recent elections, swung from narrowly GOP in 2004 to narrowly Democratic in 2008. [Figure 2 and Table 1 about here] Most remarkably, though the GOP had carried Indiana by 21 points in 2004, Obama’s extensive ads and ground game there helped him squeeze out a narrow 25,000 vote statewide win. In examining the Indiana results, analyst Michael Barone concluded: “Organization matters. I was not sure how much the Obama organization could deliver in actual votes. The answer turns out to be a lot. The Indiana results are very impressive” (Barone 2008). Barone 17 noted that lopsided swing in that state probably resulted from the lack of a strong GOP organization resulting from the state’s previously reliable GOP voting pattern. In the traditionally competitive state of Ohio, in contrast, where the GOP had long been organized for hard-fought contests, the Obama swing was much smaller. The Obama organization proved its ability to greatly “expand the playing field” much to their advantage. In contrast, McCain made no inroads into the Democratic Electoral College base. His campaign made concerted efforts in the final phases of the campaign in two traditionally blue states – New Hampshire and Pennsylvania – but lost both decisively. Throughout his 2008 campaign, Obama decried the polarization and division besetting America. He first criticized it in his celebrated 2004 address to the Democratic National Convention: “The pundits like to slice-and-dice our country into Red States and Blue States; Red States for Republicans, Blue States for Democrats. But I've got news for them, too. We are one people . . .” One ironic result of the 2008 popular vote was that, despite Obama’s impressive victory, the statewide results evidenced even more polarization than in 2000 and 2004, in fact more than had any election since 1948. Counting the number of states where the winner’s share of the statewide vote was at least ten points higher or lower than his nationwide vote, 2008 produced eighteen states with such polarized results, compared to sixteen in 2000 and fifteen in 2004. Only one election from 1948-1996 (in the tumultuous year of 1968, with fifteen) featured more than eleven such polarized states. What does this mean? Obama’s great popularity in blue states and Palin’s strong appeal in red states may have augmented polarization in 2008. Polarization does not just result from George W. Bush’s presence on the ballot, but instead may be an enduring feature of our politics. Unity, a major theme in Obama’s campaign rhetoric, may not be so easy to achieve during his presidency (Cost 2008). 18 The Obama win hinged on the support of four demographic groups: African Americans, Latinos, young voters, and highly educated voters. Table 2 reveals that Obama scored resounding (95 percent) support among African-Americans, whose ranks grew from eleven percent of the electorate in 2004 to thirteen percent in 2008. Some analysts claimed before the election was that Obama’s race might cost him votes. Only nine percent of voters, however, said race was a factor in their presidential vote, and a majority of them favored Obama. Latinos also voted much more Democratic in 2008 than in 2004 (increasing from 53 to 67 percent) and their percentage of the electorate increased by one percent. Since the Latino share of the American population and electorate is bound to increase in coming years, that is very good news for Democrats. One of the most remarkable shifts in the election was the large margin Obama gained among voters aged 18-29. His 24-point advantage was vastly larger than John Kerry’s nine-point edge in 2004. Young voters, like Latino voters, portend the future of the American electorate. Obama narrowly carried college graduates, a group that the GOP won regularly in previous elections, and also carried those with post-graduate degrees by a whopping eighteen points, besting Kerry’s 2004 margin by seven points. These groups also will grow as a percentage of the electorate in future years should education levels continue to rise, as is likely. Obama also narrowly carried the suburbs, a crucial area of swing voters. Obama carried every state where he equaled or exceeded his national level of fifty percent of the suburban vote. The future of the 2008 Democratic coalition, judged by these demographic trends, seems bright. Exit polls reported that overall, the Democrats enjoyed a seven point advantage over Republicans in the 2008 electorate – 39 to 32 percent – up from a 37-37 tie in 2004, the biggest partisan shift across two consecutive elections since exit polling began. [Table 2 about here] 19 In contrast, where did McCain score well? McCain carried white voters, but the white proportion of the electorate shrank by three percent – from 77 to 74 percent – and McCain’s margin among them was five points less than gathered of Bush in 2004. He also won rural and older voters by comfortable margins. The rural population is not growing as a proportion of the American population. Older voters will not help build future Republican majorities unless some of the more Democratic younger voters change their minds over time. For future electoral success, the GOP will have to reach beyond older, white and rural voters. McCain suffered from the two central factors mentioned at the beginning of the chapter: George W. Bush’s low job approval and concerns over a declining economy. McCain won every state where Bush’s job approval was over 35 percent in the exit polls and lost every state where Bush’s job approval was below 35 percent (except Missouri, which McCain carried by less than 4,000 votes). Fully 85 percent of voters were “very worried” about economic conditions, and Obama carried these voters by ten points, 54-44 (Cable News Network 2008). The scale of Obama’s success in the 2008 is unusual and impressive. He greatly expanded the number of states in which his party was electorally competitive for the presidency. He won comfortably among groups that will make up a steadily larger proportion of future electorates. He increased his margins among his partisans while also converting groups of swing voters, such as independents, moderates and suburbanites. He did this by raising vast sums, deploying it ably to flood the airwaves with ads and create the largest grassroots organization in modern campaign history, all the while personally demonstrating constant message discipline, in contrast to running mate Joe Biden’s occasional gaffes. One of the greatest accomplishments of the Obama campaign was its paucity of mistakes. That may seem unimportant, but consider the cost of the McCain campaign’s mistakes during the fall campaign and the smooth running 20 Obama campaign seems all the more remarkable. Oh, and one more unusual fact -- all this was accomplished by the first African American to win the White House in our nation’s history. The Broader Consequences Do the solid Democratic presidential and congressional victories of November 4, 2008 betoken a long-term transformation of American politics? Election scholars coined the term “realignment” to connote an unusual election or series of elections that reconfigures electoral politics for the long term. Such elections feature sharp changes in issues, party leaders, the regional and demographic bases of power of the two parties that create a new competitive situation in national elections. The last definitive realignment occurred in 1932, when a Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s landslide election brought new groups -- African Americans, blue collar workers -- into an enlarged Democratic coalition and reshaped electoral competition around a variety of new social welfare issues. The “New Deal coalition” dominated American politics until the 1960s, when it gradually was displaced by an era of more evenly contested presidential and congressional elections. Might the big Democratic victory of 2008 be the start of a partisan realignment? We won’t know the answer to that for several years, because enduring changes are only evident after much time has passed. Even so, there are reasons to doubt that realignment began in 2008. Realigning election feature sharp changes in voting behavior and party allegiances get rearranged. No such sharp shifts occurred in 2008. Political scientist Larry Bartels analyzed state results in 2008 and found them very similar to those of the close election of 2004. Democrats just gained a few more votes among groups across the board; no big shifts in allegiance occurred. The overall shift in the Democratic margin was 29 points in 1932 compared to 9 points in 2008. Bartels found the 2004-8 continuity greatly contrasted with the shifting 21 state patterns of the 1932 election (Bartels 2008). The Democratic gains in Congress were more similar in size to the GOP gains in the midterm election in 1994, which was not a realigning election, than they were to the mammoth Democratic gains of 1932. Further, the election did not result from the surging popularity of the Democratic Party, but rather from the unpopularity of the GOP. In a November 2008 survey, Democrats were about as popular with voters in 2008 as they were in 2004, when they lost the presidency and Congressional seats, while the GOP had dropped in popularity by a big margin (Democracy Corps 2008). Overall, it seems the unprecedented financial crisis of September 2008 magnified a narrow Democratic lead into a substantial November victory. Figure 1 reveals that Obama’s lead surged in late September. Scott Winship draws the appropriate conclusion: “Without the financial crisis, the already weak economy might not have been enough to give Obama his swing states [several of which he won by very narrow margins]. In that case, we would have seen our third straight “50-50 Nation” election. Barring financial crises every four years, that’s no recipe for realignment” (Winship 2008). Prospects for the Parties To prosper, the GOP really must move on from the issues and leaders of 2008. The unpopular George W. Bush will leave the White House, opening up possibilities for new leaders and new coalition construction. But that task will not be easy. The GOP traditionally enjoyed a reputation as the superior party at government management and the maintenance of national security. The many miscues of the George W. Bush presidency – Iraq and Hurricane Katrina, for example – have deeply tarnished that reputation. The immediate concerns of American involve their endangered economic security. The GOP, traditionally the party of limited government and free markets, is not positioned well to meet those needs in the short term. A rethinking of the 22 GOP policy agenda must occur for the party to expand its electoral prospects in the future. And that rethinking is best led publicly by new leaders better able to appeal to a demographically changing electorate. The Democrats now have an unusual opportunity to dominate national policymaking for the first time since they controlled the Congress and Presidency in 1993-4. But they have asked for, and gained, the power to address a daunting set of problems. America was headed into its deepest recession in almost thirty years as Obama took office, making economic stimulus a top priority for the new president. But other troublesome issues crowded the agenda: health care reform, environmental problems, historically large governmental deficits, ongoing military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, international terrorism. How soon must government by Democrats produce results meeting the American public’s approval in order for the party to retain its hold on power? And when will Republicans be seen to offer a credible alternative? The answers to such questions are hostage to events, as was the 2008 presidential election. As Walter Dean Burnham, a leading scholar of American elections put it: “There’s a huge amount of instability that’s built into the electoral system right now. Hegemony tends to erode pretty quickly” (Harwood 2008). Works Cited Bartels, Larry. 2008. Election Debriefing. Center for the Study of Democratic Politics. Princeton University. http://blogs.princeton.edu/election2008/2008/11/election-debriefing.html (accessed November 7, 2008). Bartels, Larry M. and John Zaller. 2001. “Presidential Vote Models: A Recount.” PS: Political Science and Politics 34 (1): 9–20. 23 Cable News Network. 2008. “National President Exit Poll.” http://www.cnn.com/ELECTION/2008/results/president/ (accessed November 10, 2008). Center for the Study of the American Electorate. African Americans, Anger, Fear and Youth Propel Turnout to Highest Level Since 1964. American University. http://domino.american.edu/AU/media/mediarel.nsf/1D265343BDC2189785256B810071F238/E E414B16927D6C9E85257522004F109D?OpenDocument Cost, Jay. 2008. “Electoral Polarization Continues Under Obama.” http://www.realclearpolitics.com/horseraceblog/ (accessed November 20, 2008). Cox, Ana Marie. 2008. “McCain Campaign Autopsy.” Daily Beast, November 7. http://www.thedailybeast.com/blogs-and-stories/2008-11-07/mccain-campaign-autopsy//p/ (accessed November 7, 2008). Democracy Corps. 2008. “Post-Election Survey with Campaign for America’s Future.” http://www.democracycorps.com/download.php?attachment=dcor110508fq1.pdf (accessed November 25, 2008). Harwood, John. 2008. “The End of Political Dominance.” New York Times, October 27. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/27/us/politics/27caucus.html?ref=todayspaper (accessed October 27, 2008) Jones, Jeffrey. 2008. “Economy Runaway Winner as Most Important Problem.” http://www.gallup.com/poll/112093/Economy-Runaway-Winner-Most-Important-Problem.aspx (accessed November 22, 2008). Lizza, Ryan. 2008. “How Obama Won.” New Yorker, November 17. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/11/17/081117fa_fact_lizza?printable=true (accessed November 17, 2008). 24 McDonald, Michael. 2008. 2008 Unofficial Vote Count. George Mason University. http://elections.gmu.edu/preliminary_vote_2008.html (accessed December 11, 2008). Stimson, James A. 2008. Bounce and Counterbounce. University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. http://www.unc.edu/~jstimson/comment.htm (accessed September 22, 2008). Sullivan, Amy. 2008. “Undecideds Laughing At, Not With, McCain.” Time magazine Swampland blog http://swampland.blogs.time.com/2008/10/16/ (accessed November 20, 2008). York, Byron. 2008. “John McCain, Against the Wind.” National Review online, October 27. http://article.nationalreview.com/?q=NjI1MDk3NzU1NjI1ODQ1Mjc1NWFkNGNlMTMxYTc3 NzY= (accessed October 28, 2008). Winship, Scott. 2008. “America the Polarized.” The New Republic, November 6. http://www.tnr.com/politics/story.html?id=68e1a802-539d-4443-9a73-4901ce151188 (accessed November 6, 2008). 25 Figure 1: National President General Election Poll Trend: Obama and McCain Source: pollster.com. The polling trend lines go through the "middle" of the data, with an average error of zero. The trend estimate smoothes out daily fluctuations in the polls; it is not a raw average of daily polls. The figures listed above the graph are the final, election day poll estimates for each candidate. Created by Charles Franklin, University of Wisconsin-Madison. 26 Figure 2: Electoral Vote Map for the Two Major Parties, 2004 and 2008 27 28 Table I: Popular and Electoral College Vote results in the 2004 and 2008 Presidential Elections State Electoral Vote 2008 Electoral Vote 2004 Popular Vote 2008 McCain Bush McCain Obama Kerry Obama Popular Vote 2004 Popular Vote 2008 (%) Popular Vote 2004 (%) Bush McCain Bush Kerry Obama Kerry Alabama 9 9 1,264,879 811,764 1,176,394 693,933 61 39 63 37 Alaska 3 3 192,631 122,485 190,889 111,025 60 38 61 36 Arizona 10 10 1,132,560 948,648 1,104,294 893,524 54 45 55 44 Arkansas 6 6 632,672 418,049 572,898 469,953 59 39 54 45 4,554,643 7,441,458 5,509,826 6,745,485 37 61 44 54 1,020,135 1,216,793 1,101,255 1,001,732 45 54 52 47 California 55 55 Colorado 9 Connecticut 7 7 620,210 979,316 693,826 857,488 38 61 44 54 Delaware 3 3 152,356 255,394 171,660 200,152 37 62 46 53 Dist. Of Col. 3 3 14,821 210,403 21,256 202,970 7 93 1 89 9 29 Florida Georgia 27 15 Hawaii Idaho 27 3,939,380 4,143,957 3,964,522 3,583,544 49 51 52 47 15 2,048,244 1,843,452 1,914,254 1,366,149 52 47 58 41 120,309 324,918 194,191 231,708 27 72 45 54 400,989 235,219 409,235 181,098 61 36 68 30 1,981,158 3,319,237 2,346,608 2,891,989 37 62 45 55 4 4 4 4 Illinois 21 Indiana 11 11 1,341,667 1,367,503 1,479,438 969,011 49 50 60 39 7 7 677,508 818,240 751,957 741,898 45 54 50 49 Iowa 21 Kansas 6 6 685,541 499,979 736,456 434,993 57 41 62 37 Kentucky 8 8 1,050,599 751,515 1,069,439 712,733 58 41 60 40 Louisiana 9 9 1,147,603 780,981 1,102,169 820,299 59 40 57 42 Maine 4 4 296,195 421,484 330,201 396,842 41 58 45 53 Maryland 10 10 956,663 1,612,692 1,024,703 1,334,493 37 62 43 56 Massachusettes 12 12 1,104,284 1,891,083 1,071,109 1,803,800 36 62 37 62 Michigan 17 17 2,044,405 2,867,680 2,313,746 2,479,183 41 57 48 51 Minnesota 10 10 1,275,409 1,573,354 1,346,695 1,445,014 44 54 48 52 Mississippi 6 6 687,266 520,864 672,660 457,768 57 43 59 40 Missouri 11 11 1,445,812 1,442,180 1,455,713 1,259,171 50 49 53 46 Montana 3 3 241,816 229,725 266,063 173,710 50 47 59 39 Nebraska 4 5 448,801 329,132 512,814 254,328 57 42 66 32 1 30 Nevada 5 New Hampshire 4 New Jersey 15 New Mexico 5 New York 31 North Carolina 15 North Dakota 3 Ohio Oklahoma 20 7 Oregon 5 411,988 531,884 418,690 397,190 43 55 51 48 4 316,937 384,591 331,237 340,511 45 54 49 50 15 1,545,495 2,085,051 1,670,003 1,911,430 42 57 46 53 343,820 464,458 376,930 370,942 42 57 50 49 2,576,360 4,363,386 2,962,567 4,314,280 37 62 40 58 15 2,109,698 2,123,390 1,961,166 1,525,849 49 50 56 44 3 168,523 141,113 196,651 111,052 53 45 63 36 20 2,501,855 2,708,685 2,859,764 2,741,165 47 51 51 49 7 959,745 502,294 959,792 503,966 66 34 66 34 5 31 7 7 699,673 978,605 866,831 943,163 41 57 47 52 Pennsylvania 21 21 2,586,496 3,192,316 2,793,847 2,938,095 44 55 49 51 Rhode Island 4 4 165,389 296,547 169,046 259,760 35 63 39 59 South Carolina 8 8 1,034,500 862,042 937,974 661,699 54 45 58 41 South Dakota 3 3 203,019 170,886 232,584 149,244 53 45 60 38 Tennesee 11 11 1,487,564 1,093,213 1,384,375 1,036,477 57 42 57 43 Texas 34 34 4,467,748 3,521,164 4,526,917 2,832,704 55 44 61 38 Utah 5 5 555,497 301,771 663,742 241,199 63 34 73 26 98,791 219,105 121,180 184,067 31 68 39 59 Vermont 3 3 31 Virginia 13 Washington 11 West Virginia 5 Wisconsin Wyoming Totals 13 11 5 10 3 173 10 3 365 286 252 1,726,053 1,958,370 1,716,959 1,454,742 47 53 54 46 1,098,072 1,548,654 1,304,894 1,510,201 41 58 46 53 394,278 301,438 423,550 326,541 56 43 56 43 1,258,181 1,670,474 1,478,120 1,489,504 43 56 49 49 160,639 80,496 167,629 70,776 65 33 69 29 58,343,671 66,882,230 62,028,719 59,028,550 46 53 Sources: Cable News Network and New York Times. 32 Table 2: Group Support in the 2004 and 2008 Presidential Elections 2008 Voters % 2004 Voters % Characteristic For McCain (%) For Obama (%) For Bush (%) For Kerry (%) Party 39 37 Democrat 10 89 11 89 32 37 Republican 90 9 93 6 29 26 Independent 44 52 48 49 Ideology 22 21 Liberal 10 89 13 85 44 45 Moderate 39 60 45 54 34 34 Conservative 78 20 84 15 Ethnic Group 74 77 White 55 43 58 41 13 11 Black 4 95 11 88 9 8 Hispanic 31 67 44 53 2 2 Asian 35 62 44 56 Sex/ethnicity 36 36 White men 57 41 62 37 39 41 White women 53 46 55 44 5 5 Black men 5 95 13 86 7 6 Black women 3 96 10 90 Sex/marital status 33 30 Married men 53 45 60 39 32 32 Married women 50 47 55 44 14 16 Unmarried men 38 59 45 53 33 21 22 Unmarried women 29 71 37 62 Age 18 17 18-29 years old 32 66 45 54 29 29 30-44 years old 46 52 54 46 37 30 45-59 years old 49 50 51 48 16 24 60 years and older 53 45 54 46 35 63 49 50 Education 4 4 Not a HS Grad 20 22 HS Graduate 46 52 52 47 31 Some College 32 Education 47 51 54 46 28 26 College Graduate 48 50 52 46 17 Post-Graduate 16 Education 40 58 44 55 Religion 54 54 Protestant 54 45 59 40 42 40 65 34 58 40 26 White 22 Evangelical 74 24 77 22 15 Attend church 42 weekly 67 32 70 29 27 27 Catholic 45 54 52 47 12 Attend church 12 weekly 50 49 55 44 21 78 45 74 25 73 36 63 37 60 42 57 2 White Protestant 3 Jewish Family Income 6 12 8 Under $15K 15 $15,000-$29,999 34 19 22 $30,000-$49,999 43 55 49 50 62 58 Over $50,000 49 49 56 43 41 32 Over $75,000 49 49 57 42 26 18 Over $100,000 49 49 58 41 21 24 Union Household 42 57 40 59 15 18 Veterans 54 44 57 41 Size of Place 30 32 Urban 35 63 44 55 49 53 Suburban 48 50 51 48 21 16 Rural 53 45 58 40 Most important issue 63 20 Economy 44 53 18 80 10 15 Iraq 39 59 26 73 19 Terrorism 86 13 86 14 26 73 23 77 9 9 8 Health Care Source: National exit polls collected by Cable News Network. 35 1 Eight different 2008 general election prediction models are discussed in PS Political Science and Politics, Volume XLI Number 4 (October 2008), pp. 679-722. 36