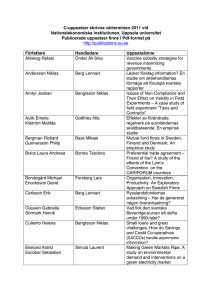

Mikro Sammanfattning 2425KB Sep 10 2013 04:46:35

advertisement

Mikro- och Allokeringsteori, Kurs 404 Denna sammanfatting är inte helt färdig. Men jag antar att det är bättre att lägga upp den nu än att lägga upp den efter omtentan =) (2004-01-03) Har kollat igenom den en gång nu så de flesta fel har nu blivit korrigerade. Märkte också att jag råkade sammafatta kapitel 14 som inte är med på tentan. Har dock inte tagit bort den. (2004-01-05) Claes Melander, 19701 1 Sammanfatting av Mikroekonomikursen Av Claes Melander 19701, 2004-01-02 Källor: ”Microeconomics” Perloff, third edition samt föreläsningsmaterial Chapter 1 – Introduction Microeconomics: the allocation of scarce resources – how the individual or the company allocate his resources to receive the most benefits. Society’s three main allocation decisions: Which goods are produced How they are produced Who gets the goods Positive statement: testable hypothesis about cause and effect. (Faktabaserade teorier) Normative statement: Value judgements, cannot be tested. (Åsiktsbaserade teorier) Chapter 2 – Supply and Demand Supply function depends on cost (such as interest rates, wage rates, and the cost of raw materials, production cost), rules and regulations Demand function depends on price of the good, price of similar goods, income, taste, rules and regulations Law of Demand – Demand curves slope downward Shocking the equilibrium: A change in an underlying factor other than price causes a shift ot the supply or demand curve, which alters the equilibrium. Price Control Maximipris (Price ceiling) - Kan leda till överskottsefterfrågan (Excess demand) då priset sätts lägre än vad det skulle vara utan statlig inblandning. Minimilön (Price floor) – Kan leda till utbudsöverskott (Excess supply) eller arbetslösthet som är fallet med minimilön. Perfectly competitive markets Everyone is a price taker: Because no consumer or firm is a very large part of the market, no one can affect the market price. Easy entry of firms into the market, which leads to a large number of firms, is usually necessary to ensure that firms are price takers. Firms sell identical products: Consumers do not prefer one firm’s good to another Everyone has full information about the price and quality of goods: Consumers know if a firm is charging a price higher than the price others set, and they know if a firm tries to sell them inferior-quality goods. Costs of trading are low: It is not time consuming, difficult, or expensive for a buyer to find a seller and make a trade or for a seller to find and trade with a buyer Claes Melander, 19701 2 Chapter 3 - Applying the Supply-and-Demand Model Om en input som påverkar efterfråge- eller utbudskurvan ändras, så ändras också jämviktspriset. En skiftning av utbudskurvan ger en förflyttning längs efterfrågekurvan, och vice versa. Elasticities of Supply and Demand Generally, elasticity is a measure of the sensitivity of one variable to another. It tells us the percentage change in one variable in response to a one percent change in another variable. Oelastisk: 0 > > -1 Elastisk: < -1 Perfekt Oelastisk: = 0 Vertikal kurva. (Ger oändlig skillnad i pris vid förändring i utbudet/efterfrågan, men ingen skillnad i efterfråga. Exempelvis livsnödvändiga medikament) Perfekt elastisk: = -∞ Horisontell kurva (Ger oändlig skillnad i kvantitet vid förändring i utbudet, men ingen skillnad i pris. Omfattas av relativt ”onödiga” varor) Inelastisk: Låg förändring (i kvantitet vid prisförändring) Elastisk: Stor förändring (i kvantitet vid prisförändring) Långsiktig elasticitet är oftast större än kortsiktig, på grund av substitutionsfaktorer och lagringsmöjligheter. Om varan lätt kan lagras, är dock kortsiktiga mer elastiska än långsiktiga, Efterfrågans priselasticitet Efterfrågekvantitetens känslighet vid ändringar i pris. Measures the sensitivity of quantity demanded to price changes. It measures the percentage change in the quantity demanded for a good or service that results from a one percent change in the price. The primary determinant of price elasticity of demand is the availability of substitutes. Many substitutes: demand is price elastic Few substitutes: demand is price inelastic = procentuell förändring i efterfrågekvantitet = ( Q/Q) = procentuell förändring i pris ( p/p) Linjär efterfrågekurva, ger = Claes Melander, 19701 Q p = D´(p)* p pQ Q Q p = -b*p där -b är lutningen på kurvan pQ Q 3 Då på en linjär efterfrågekurva har vi en Unitary elasticity: A 1% increase in price causes a 1% fall in quantity. Law of Demand Minskat utbud vid prisökning visas genom negativ priselasticitet. Perfectly Elastic Demand Consumers very sensitive to price change If the price increases even slightly above p*, demand falls to zero. Thus a small increase in price causes an infinite drop in quantity, so the demand curve is perfectly elastic Perfectly Inelastic Demand Consumers not sensitive to price change If price goes up, the quantity demanded is unchanged, so the elasticity of the demand must be zero. A demand curve is vertical for essential goods Inkomstelasticitet (av efterfrågan) Efterfrågans känslighet mot förändringar i inkomst Income elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in quantity demanded resulting from a one percent change in income. = procentuell förändring i efterfrågekvantitet = ( Q/Q) = procentuell förändring i inkomst ( I/I) Q I IQ Korspriselasticitet (av efterfrågan) Efterfrågans känslighet mot prisändringar hos en annan vara. procentuell förändring i efterfrågekvantitet = ( Q/Q) = procentuell förändring i en annan varas pris ( pL/pL) Q pL pL Q Negativ elasticitet: Komplementvaror (När andra varan ökar i pris köps mindre av vår vara) Positiv elasticitet: Substitut (När andra varan ökar i pris köps mer av vår vara) Utbudets priselasticitet: Utbudets känslighet vid ändringar i pris. = procentuell förändring i utbudskvantitet = procentuell förändring i pris Claes Melander, 19701 Q/Q = p/p Qp pQ 4 Skatt Ad Valorem Exempelvis moms. Staten tar en viss procent av det betalda priset. Specificerad/enhetsskatt Fördelning av skattebördan p = ( - ) * Staten tar en viss summa per såld enhet. Effekter på jämvikten: Enhetsskatt höjer jämviktspriset och sänker därmed utbudet. Ju högre elasticitet på efterfrågan, desto mindre ändring i jämviktspriset vid pålägg av skatt. (utbudetselasticiteten hålls konstant) Under perfekt konkurrens vältras inte hela förändringen över i priset. Högre övervältring när utbudselasticiteten är hög och när efterfrågeelasticiteten är låg. Påverkan av en skatt bestäms av relativiteten efterfråga/utbud. Hur mycket av skatten som betalas av konsumenterna ges av = utbudselasticitet . ( - ) utbudselasticitet – efterfrågeelasticitet Om efterfrågekurvan har negativ lutning (neråt) och utbudet positiv (uppåt), betalas pålagd skatt inte enbart av konsumenterna. Claes Melander, 19701 5 Chapter 4 - Consumer Choice Konsumentens preferenser bestämmer hur stor nytta denne har av en vara/service. (Individual tastes or preferences determine the amount of pleasure people derive from the goods and services they consume.) Konsumenten möts av begränsningar. (Consumers face constraints of limits on their choices.) Konsumenten maximerar sin nytta utifrån dessa begränsningar. (Consumers maximize their well-being or pleasure from consumption, subject to the constraints they face.) PREFERENSER Completeness – The consumer prefers the first bundle to the second, prefers the second to the first, or is indifferent between them. (Kompletta) Transitivity – A>B and B>C therefore A>C (Transitiva) More is Better – More ”Goods” are preferred to less ”Goods”. Less “Bads” are preferred to more “Bads” (Always wanting more is known as nonsatiation) Indifferenskurva Olika kombinationer av två varor som ger samma nivå av nytta, dvs anses likvärdiga. Egenskaper Större nytta ju längre bort från origo. Alla kombinationer av varor ger en viss nyttonivå, dvs det går en differenskurva genom varje varukorg Indifferenskurvor kan inte korsa varandra, inte vara ’tjocka’ Lutar neråt. Konvexa vid konsumerande av positiva kvantiteter. Kan även vara koncava Bytesförhållanden Perfekta substitute - Kännetecknas av linjära indifferenskurvor Perfekta komplement - Mer av vara x bara värdefullt tillsammans med mer av vara y. Claes Melander, 19701 6 NYTTA Nyttofunktion (Utility fuction) En formel som visar den totala nyttan associerad med en varukorg Marginalnytta (Marginal Utlility) Marginalnyttan av en viss vara är den extra nytta som individen får av att konsumera ytterligare en enhet av den varan. Lutningen på nyttofunktionen. Positiv, men avtagande. Konsumentens begränsade val Att välja den varukorg som maximerar nyttan Marginal Rate of Substitution Lutningen på differenskurvan. Den talar om hur mycket individen är villig att avstå av y för att få en extra x, givet samma nytta. MRS = -MUX MUY BUDGETRESTRIKTION Alla kombinationer av varor som kan köpas. Mäter ej nyttan, bara budgeten. Budgetrestriktion vid inkomsten I och köp av vara y och vara x. I = px * x + py *y y = I / py – (px / py)x Marginal Rate of Transformation Lutningen på budgetrestriktionen Derivatan av budgetrestriktionskurvan MRT = - pX Py Interior solution - When optimum Indifference curve lies as a combination of the two goods. Corner Solution - When optimum Indifference curve lies by axis consisting of only one good BEGRÄNSAT VAL FÖR KONSUMENTEN Maximeringspunkt Indifferenskurvan tangerar budgetrestriktionen Konsumenten väljer den högsta indifferenskurvan MRT = MRS (Derivatan av budgetrestriktionskurvan = Derivatan av indifferanskruvan) Sista kronan som läggs på vara 1, ger lika mycket nytta som den sista kronan som läggs på vara 2 MRT = MRS - pX = - MUX Py MU Claes Melander, 19701 MUX = pX MUY pY eller MUX = MUY pX pY 7 Chapter 5 - Applying Consumer Theory INKOMSTELASTICITET = procentuell förändring i efterfrågekvantitet = ( Q/Q) = procentuell förändring i inkomst ( I/I) Q I I Q Normal vara Större efterfrågan vid ökad inkomst. Inferiör vara Lägre efterfrågan vid ökad inkomst. Härledning av efterfrågekurvan Visar hur efterfrågan ändras när budgetrestriktionen ändras. I det här fallet skiftar budgetrestriktionen på grund av ett sjunkande öl-pris. Pris-konsumtionskurvan Uppåtlutande kurva visar på positiva inkomstelasticiteter för vara x och y. Bakåtlutande kurva visar att vara y är normal och vara x inferiör. Neråtlutande mot x-axeln visar att vara y är inferiör och vara x normal. Båda varor kan inte vara inferiöra. En vara kan variera mellan inferiör och normal efter olika inkomstnivåer. Exempelvis arbetsutbudskurvan. Inkomst-konsumtionskurva Samma som pris-konsumtionskurvan men här ändras inkomst och inte pris på en vara. (se fig nästa sida) Claes Melander, 19701 8 Engelkurva Visar relationen efterfrågekvantitet – inkomst, när priserna hålls konstanta Prisfall har två effekter på efterfrågan Substitutionseffekten (e1 e*) (SE) Konsumenten köper mer av varan för att den är billigare i jämförelse med andra varor på marknaden. Konsumenten substituerar, väljer den billigare varan. Visar ändring i efterfrågad kvantitet från en kompenserad ändring i varans pris. Inkomsteffekten (e* e2) (IE) Inkomsten blir för högre än varans pris, varans sänkta pris driver upp konsumentens köpkraft. Inkomst effektens riktning beror på inkomstelasticiteten. Ändring i efterfrågan av en vara beroende av inkomsten, där priset är hållt konstant. Claes Melander, 19701 9 Total effekt Räknas ut genom att dra den nya budgetrestriktionen (L2) och därmed flytta till en högre indifferenskurva (I2), därefter ritar man in en imaginär kurva (L*) med samma lutning som den nya budgetrestriktionen (L2) så att den tangerar den nya indifferenskurvan (I1). Flytten från jämvikten e1 till e* visar då substitutionseffekten, varefter inkomsteffekten kan studeras i flytten från e* till jämvikten e2. Den totala effekten kan därefter bedömas. Normal (Fig 5.5) (SE och IE går åt samma håll) Positiv inkomsteffekt + positiv substitutionseffekt = positiv total effekt. Efterfrågas mer när inkomsten ökar eller priset på varan minskar. Exempel: Kläder, restaurantbesök. Inferiör (IE motverkar SE, går åt olika håll) Negativ inkomsteffekt + positiv substitutionseffekt = negativ eller positiv total effekt. Efterfrågas mindre när inkomsten ökar. Skapar en uppåtlutande efterfrågekurva Exempel: Nudlar, blodpudding. Giffen (Fig 5.6) (IE motverkar SE och IE>SE) Negativ inkomsteffekt + positiv substitutionseffekt = negativ total effekt. Efterfrågas mindre när priset på varan minskar. (Motsäger Law of Demand, dock är lagen endast en emprisk regularitet och inte ett teoretiskt faktum) Exempel: När priset på bio faller kan Erik gå och se fler bio filmer, trots detta lägger Erik ner mer pengar på att köpa fotbollsmatchbiljetter och mindre på biobiljetter. Biobijetter efterfrågas alltså mindre trots att priset sjunker i Eriks fall. (bio = Giffen) OBS! En giffen-vara är alltid inferiör, medan en inferiör vara inte behöver vara en giffen-vara Konsumentprisindex och lönekompensation Applicera ovanstående teorier och se att full lönekompensation för KPI är en överkompensation. Gör ett true cost-of-living index (inflationsindex där nytta (indifferencekurvan) är hållt konstant över tiden) med hjälp av tekniken för att identifiera substitions- och inkomsteffekt. Arbete – Fritid En ökad lön leder till såväl inkomstsom substitutionseffekter. Inkomsteffekten leder till ökad mängd arbetstid om det är en normal vara, substitutionseffekten leder till ökad mängd fritid om fritid är en normal vara. Depending on whether leisure is an inferior or normal good, the supply curve of labor may be upward sloping or backward bending Sparande Kan också beräknas som en vara. Claes Melander, 19701 10 Chapter 6 - Firms and Production Kortsiktigt Period då vissa insatsfaktorer är fasta medans andra är variabla. Långsiktigt Period då alla insatsfaktorer är variabla. Produktionsfunktionen q = f(L, K) Beskriver största tekniskt möjliga produktionsvolym vid olika (minimala) kombinationer av produktionsfaktorer. Produktion med en insatsfaktor (Kortsikt) Produktionsfunktionen q = F(L) Genomsnittsprodukten - APL (Average Product of Labor) Förhållandet arbetskraft och totalproduktion ges av Total produktion/antalet arbetare APL = q APL = F(L) L L Marginalprodukten - MPL (Margianl Product of Labor) Ändringen av produktionen när man ökar arbetskraften med en enhet. Ges av tangenten till Total Produktion vid en given punkt. MPL = f L MPL = F’(L) Total produktion (TP) Hur stor output som kan produceras av en viss mängd av inputen. Figur 6.1 Produktion när arbetskraft är en variabel insatsfaktor Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns Om ett företag endast ökar en input samtidigt som de andra faktorer hållna konstanta blir ökningarna i output marginellt lägre och lägre. Claes Melander, 19701 11 Produktion med två insatsfaktorer (Långsikt) Isokvant Samma kvantitet Jämför indifferenskurvor. Visar olika kombinationer av K och L som precis kan producera en given nivå av en vara. Uttrycker möjliga tekniska bytesförhållanden i företaget, mellan K och L, utan att q (output) ändras. MRTS (Marginal Rate of Technical Substution) Marginella tekniska substitutionskvoten = lutningen på isokvanten. Hur många enheter K som krävs för att substituera för L, och ge samma output. MRTS = _ förändring i K = _ K förändring i L L Diminishing MRTS Skalavkastning Skalavkastning är ett uttryck för vad som händer med åtgången på produktionsfaktorer när företaget ändrar sin produktionsvolym. Antag att företaget fördubblar insatsen av alla produktionsfaktorer ( Konstant skalavkastning: Produktionen fördubblas F(L, K) = F(K, L) för >1 Avtagande skalavkastning: Produktionen ökar mindre än dubbelt F(L, K) < F(K, L) för >1 Tilltagande skalavkastning: Produktionen ökar mer än dubbelt F(L, K) > F(K, L) för >1 Claes Melander, 19701 12 Diseconomies of Scale När ett företags genomsnittskostnad ökar då output ökar 1. The Ownership and management of firms: Sole proprietorships o smaller firms, owners run firm Partnerships o smaller firms, owners run firm Corporations o Owners hire managers o Owners want to maximize profits 6. Productivity and technical change: Relative productivity o Firms output q, Most productive firms output q* o 100q/q* = Relative productivity Technical Progress o Neutral Technical change – Produce more with same inputs o Nonneutral Technical change – Production proportions altered Long-run average cost curve: the lower bound of all the short-run average cost curves. Its shape is tied closely to returns to scale. Economies of scale: long-run average costs fall as output rises. Diseconomies of scale: long-run average costs rise as output rises. Economies of scope: less expensive to produce goods jointly than separately. Claes Melander, 19701 13 Chapter 7 - Costs Alternativkostnad Economic or Opportunity cost o The value of the best alternative use of a resources Det man måste avstå ifrån för att få det man faktiskt väljer Vad en resurs kan ge i bästa alternativa användning Explicit costs A firm’s direct, out of the pocket payments for inputs to production during a given time period Implicit costs Work time value of owner’s and value of other resources used but not purchased Kortsiktiga kostnader Fast kostnad (F) Är en produktionsutgift som inte är en variabel till output. Kan inte varieras kortsiktigt. Exempel; stora maskiner, plantage Variabel kostnad (VC) Kostnaden för variabla inputs, kan justeras efter output kvantitet. Exempel; arbete och material Total kostnad (C) C = VC + F Marginell kostnad (MC) Lutningen på kostnadskurvan C. (För kortsiktighet även samma som VC) Där MC skär AVC fås minimumpunkten till AC. MC = C eller MC = VC q q Genomsnittlig fast kostnad (AFC) AFC = F q Genomsnittlig variabel kostnad (AVC) AVC = VC q Genomsnittlig kostnad (AC) AC = AFC + AVC eller AC = C q Claes Melander, 19701 14 Långsiktiga kostnader Isokost Kostnaderna är dem samma för alla punkter utmed isokost kruvan Illustrerar alla kombinationer av K och L som kan köpas till givna relativpriser (pL/pK), för en specifik totalkostnad. C=wL + rK Kan jämföras med budgetrestriktions kurvan men viktigt att skilja är att konsumenter endast har budgetrestriktions kruva då företag kan ha flera isokostkurver beroende på deras produktion. - w/r lutningen på isokosten. Visar hur företaget måste substituera mellan K och L givet en viss produktionskostnad. Totalkostnadsekvationen TC = pK * K + pL * L => K = TC - pL * L (linjära isokost ekvationen) pK pK Kostnadsminimering Lägsta totala kostnad utifrån K och L. Den isokost som ligger närmast origo. Den sista kronan som spenderas på kapital bidrar lika mycket till produktionen som den sista kronan som spenderas på arbetskraft. Isokost och Isokvant tangering Lowest-isocost rule o Pick the bundle of inputs where the lowest isocost line touches the isoquant. Tangency rule o Pick the bundle of inputs where the lowest isoquant is tangent to the isocost line MRTS = -w/r MPL/MPK = w/r Last-dollar rule o Pick the bundle of inputs where the last dollar spent on one input gives as much extra output as the last dollar spent on any other input. (MPL/w = MPK/r) Faktorpris förändring Om faktorpriset fallar för en insatsvara kan samma isokvant nås genom en förskjuta tangeringspunkten dit man använder mer av den nu billigare instatsvaran Claes Melander, 19701 15 Chapter 8 - Competitive Firms and Markets Competitive market - Firm is a price taker Consumers believe that all firms in the market sell identical products Firms freely enter and exit the market Buyers and sellers know the prices charged by firms Transaction costs – the expenses of finding a trading partner and making a trade for a good or service other than the price paid for that good or service – are low Price taker: a firm that can't significantly affect market price for its output or inputs. Perfectly competitive market Homogeneous or undifferentiated products Imperfectly competitive market Heterogeneous or differentiated products Residual demand curve Dr(p) The demand curve that an individual firm faces in a competitive market Dr(p) = D(p) – So(p) D(p) = Demand curve in the market So(p) = Supply curve for all other firms in the market Elasticity of residual demand curve Om det finns n identiska företag i marknaden kommer efterfrågeelasiteten för företaget vara i i = nn – 1)o market elasticity of demand (a negative number) o = Elasticity of supply of the other firms (normally a positive number) n – 1 = the number of other firms Ekvationen visar att Dr(p) är mer elastisk då: Det finns fler företag, n i marknaden Efterfråge elatisiteten, är större Utbuds elatisiteten av de andra företegen, o är större Claes Melander, 19701 16 Vinst maximering R – C > 0 ger vinst < 0 ger förlust Economic profit (Normally referred to as profit) Revenue – economic cost (opportunity cost, explicit and implicit) Business profit (Normally referred to as Business profit) Revenue – only explicit costs Output decision The firm produces, what output level, q, maximizes its profit or minimizes its loss Output rules 1. The firm sets output where its profit maximized 2. A firm sets its output where its marginal profit is zero 3. A firm sets its output where its marginal revenue equals its marginal cost ´(qR´(q) – C´(q) = 0 R´(q) = C´(q) MR = MC Shutdown decision If it’s more profitable to shut down than to produce, q, it will shut down Shutdown rules 1. The firm shuts down only if it can reduce its loss by doing so 2. The firm shuts down only if its revenues is less than its avoidable cost Competition in the short run First, the competitive firm determines the output that maximizes its profit (or minimizes its loss) when its marginal cost equals the market price: MC(q) = p Claes Melander, 19701 17 Second, the firm chooses to produce that quantity unless it would lose more by operating than by shutting down. The firm shuts down only if the market price is less than the minimum of its average variable cost: p < AVC(q) Short-Run Firm Supply Curve The competitive firm’s supply curve is its marginal cost curve above its minimum average variable cost Short-Run Market Supply Curve The more identical firms producing at a given price, the flatter (more elastic) the short-run market supply curve at that price. Number of firms, n is fixed Claes Melander, 19701 18 Specifik skatt Om förtaget skattas med per enhet flyttas MC (Supply) och AC kurverna upp med och MC får en ny skärningspunkt med p, som man tillsammans med AC kan räkna ut vinsten efter skatten Competition in the long run Profit maximization Output that maximizes profits – MRL = MCL Shuts down if revenue is less than variable cost. In the long run all costs are variable. Very similar to short run except for all costs are variable The Short-Run and Long-Run Supply Curves Claes Melander, 19701 19 Entry and exit of the market will occur until firms in the market are making zero longrun profit Competitive firm's long-run supply curve: its marginal cost curve above the minimum of its long-run average cost. Long-run market supply curve is horizontal at the minimum long-run average cost if firms have free entry and exit; all firms have identical costs; and input prices are constant. Increasing-cost market: input prices rise as output rises Upward sloping supply curve Constant-cost market: Input prices stay constant as output rises Flat supply curve Decreasing-cost market: Input prices falls as output rises Downward sloping supply curve Zero profit in the long run In the long-run firms in a competitive market make zero economic profit therefore competitive firms must maximize their profits in order to survive Claes Melander, 19701 20 Chapter 9 - Applying the Competitive Model Consumer surplus (CS) The difference between what consumers are willing to pay and what the good actually costs. Calculated as the area under the demand curve and above the market price up to the quantity consumers buy. Producer surplus (PS) The amount a firm is paid minus its variable cost of production, which is profit in the long run. PS is the area below the price and above the supply curve up to the quantity that firm sells. PS = R - VC Welfare of society (W) W= CS + PS + (tax) Deadweight loss (DWL) The net reduction in welfare from loss of surplus by one group that is not offset by gain to another group from an action that alters a market equilibrium. With DWL reasoning one can claim that competition maximizes welfare because it drives price to equal marginal cost at equilibrium. P1 j1 CS = A + B +C PS = D + E P2 j2 CS = A PS = B + D DWL = ∆W = – C – E Claes Melander, 19701 21 Government policies that alter the equilibrium Taxes, price ceilings and price floor create a gap between the price consumers pay and the price firms receive. These policies force price above marginal cost, which raises the price to consumers and lowers the amount consumed. The wedge between price and marginal cost results in a deadweight loss Tariff A tax levied on imported goods Quota A statutory limit on the amount imported. An import quota and a tariff have the same affects for consumers and producers. The difference is that using a tariff the government collects revenue where import quota benefits the firms allowed to sell their goods in the market. Claes Melander, 19701 22 Chapter 10 – General Equilibrium and Economic Welfare General Equilibrium Partial-equilibrium analysis Examination of equilibrium and changes in equilibrium in one market in isolation. All other prices and goods are held fixed, meaning that we implicitly assume that no other market is affected. General-equilibrium analysis Study of how equilibrium is determined in all markets simultaneously Spillover effect An event in one market may have a spillover effect on other related markets, therefore you may receive a more accurate result using a general-equilibrium analysis instead of a partial Example: Corn Market – Soybean Market 1. (a) U0m and E0m j0m 2. Price of corn falls due foreign demand decrease 3. U0m and E1m j1m 4. Because of low corn price consumers substitute toward corn away from soybeans Demand for soybeans falls and supply for soybeans decrease (spillover effect) 5. (b) E0s falls to E2s and U0s falls to U2s j0s falls to j2s 6. (a) U0m U3m j1m j3m 7. (b) E2s E4s j2s j4s Using a partial analysis we stop at 3. with the general analysis we see that the equilibrium point in the corn market changes even further. Claes Melander, 19701 23 Trading between two people Pareto efficient An allocation of goods or services is Pareto efficient if any possible reallocation would harm at least one person; no one can be made better off without making someone worse off Om Denise och Janes handlar med varandra kommer båda få det bättre då alla punkter inom arean B är en förbättring gentemot jämnvikten i e. Alla punkter i arean B sägs vara Pareto effektiva. Vid punkten f kommer de bådas indifference kurver tangera varandra, alltså bådas Marginal rate of substitution (RS) är lika vid f. Tar man ut flera sådana punkter och drar ett linje emellan får vi en kontraktskurva. Vid denna kurva kommer ingen av parterna vara villiga att ingå i nån mer handel. Competitive exchange First Theorem of Welfare Economics The competitive equilibrium is Pareto efficient Under perfekt konkurrens är alla jämvikter effektiva. Second Theorem of Welfare Economics Any Pareto-efficient equilibrium can be obtained by competition, given an appropriate endowment Varje effektiv resursfördelning kan realiseras som en jämvikt under perfekt konkurrens, för något val av initial fördelning. •Antaganden: Perfekt information, konventionella preferenser, privata varor Claes Melander, 19701 24 Jämvikt under perfekt konkurrens • I en bytesekonomi där alla tar priserna för givna råder det jämvikt om alla kan köpa och sälja så mycket de vill till dessa priser. • Jämvikten definieras av den slutgiltiga resursfördelningen och priserna. Competition, in which all traders are price takers, leads to an allocation in which the ratio of relative prices equals the marginal rates of substitution of each person When MRSj = -Pc/Pö = MRSd We will receive a competitive equilibrium such as f Although if the price ratio would be something else then we would not end up with a competitive equilibrium Production and trading Comparative advantage Two people can achieve a better combined production if they trade. That combined production is summarized by PPF-curve Efficiency and equity The Pareto efficiency criterion reflects a value judgement that a change from one allocation to another is desirable if it makes someone better off without harming anyone else. This criterion does not allow all allocations to be ranked, because some people may be better off with one allocation and others may not be better off with another. Majority voting may not allow society to produce a consensus, transitive ordering of allocations either. Economists, philosophers, and others have proposed many criteria for ranking allocations as summarized in welfare functions. Society may use such a welfare function to choose among Paretoefficient (or other) allocations. Effektiva fördelningar (3 versioner) • En resursfördelning f är effektiv under följande tre ekvivalenta villkor. – Parternas marginella substitutionskvoter är identiska. – Det finns inget utrymme för ömsesidigt gynnsam handel. – Det existerar inga Pareto-förbättringar. Claes Melander, 19701 25 Chapter 11 – Monopoly Monoploy Profit Maximization Profit max MR = MC Marginal Revenue Curve for Monopoly Under perfect competition MR = demand curve. That is not the case for monopoly! The monopoly’s marginal revenue curve lies below the demand curve o The relationship between the two depends on the shape of the demand curve Linear demand curves always have the same relationship to MR curve o The slope of MR is twice the slope of demand curve o If Demand has slope -1 and hits Q = 24 when price is 0 Then MR has slope -2 and hits Q = 12 when price is 0 Price Elasticity of Demand MR = p (1 + 1/) MR equals zero where the demand curve has a unitary elasticity, = -1 Monopoly profit is maximized in the elastic portion of demand curve A monopoly never operates in the inelastic portion of its demand curve fig. b Shutdown Decision Short run shutdown if: AVC > p Long run shutdown if: AC > p Claes Melander, 19701 26 Market Power The ability of a firm to charge a price above marginal cost and earn a positive profit Elasticity The more elastic the demand the monopoly faces at the quantity at which it maximizes its profit, the closer the price is to its marginal cost Lerner Index (Price markup) p – MC = -1 p The more elastic the demand is, the closer (p – MC)/p is to zero, and the competitive level Effects of a shift of the demand curve A monopoly does not have a supply curve; therefore a shift in demand on a monopoly’s output depends on the shape of both its marginal cost curve and its demand curve. As a monopoly’s demand curve shifts, price and output may change in the same direction or different directions. Competition Monopoly Welfare effects of monopoly Because a monopoly’s price is above its marginal cost, too little is produced creating a deadweight loss. As a result the monopoly makes higher profit and consumers are worse off. Deadweight loss Area: C + E Claes Melander, 19701 27 Cost advantages that create monopolies Natural Monopoly A market has a natural monopoly if one firm can produce the total output of the market at lower cost than several firms could. Government actions that create monopolies Barriers of entry Governments make it difficult for new firms to obtain a license to operate Patents Nations grant patents, which give inventors monopoly rights for a limited period if time. Patent is an incentive for inventors and investors to develop new products that have a lot of R&D costs. Because the patent gives the monopoly higher profits returns. Government actions that reduce market power A government can eliminate the deadweight loss created by monopoly firms by regulating the price through e.g. a price ceiling. In the diagram we se a monopoly that has been optimum regulated. In the real world these types of regulations are hard to accomplish when governments usually lack the information necessary to set the price at the right level. A better way of achieving an optimum equilibrium is facilitate entry of new firms in the market Claes Melander, 19701 28 Chapter 12 – Pricing Why and how firms price discriminate A firm can discriminate if it has market power, knows which customers will pay more for each unit of output, and can prevent customers who pay low prices from reselling to those who pay high prices Nonuniform prices A firm earns higher profit from price discrimination than uniform pricing The firm captures some or all of the consumer surplus of customers who are willing to pay more than the uniform price The firm sells to some people who would not buy at the uniform price Types of discrimination Perfect price discrimination First-degree price discrimination Quantity discrimination and Block-pricing Second-degree price discrimination Multimarket price discrimination Third-degree price discrimination (Price discrimination often refers to multimarket price discrimination) Perfect price discrimination The firm charges customers the maximum each is willing to pay for each unit of output, the monopoly captures all potential consumer surplus and sells the efficient (competitive) level of output. The firm’s marginal revenue curve is its demand curve for a perfect price discriminating firm Quantity discrimination All customers pay the same price for a given quantity. A firm may quantity discriminate by charging customers who make large purchases less per unit than those who make small purchases Block-pricing A firm charge one price for the first few units (a block) of usage and a different price for subsequent blocks (fig a). (Fig b; normal monopoly pricing) Claes Melander, 19701 Ads Only Take s Cust omer s from Rival s 29 Multimarket price discrimination Firm profit-maximize by charging groups of consumers prices in proportion to their elasticities of demand, the group of consumers with the least elastic demand paying the highest price. The US consumers pay a higher price due to its less elastic demand curve. In each market firms profit-maximize by setting MRJ = MC = MRUS Welfare is less under multimarket price discrimination than under competition or perfect price discrimination but may be greater or less than that single-price monopoly. Two-part tariffs The firm charges a consumer a lump-sum fee (first tariff) for the right to purchase goods or services at a specified price (second tariff). E.g. telephone companies charge a monthly fee (first tariff) then they charge for calls per minute (second tariff) This method may capture all consumer surplus if consumers have identical demand curves. If consumer not are identical or the firm does not know each customer’s demand curve or can vary the two-part tariff across customers, it can use a two-part tariff to make larger profit than it can get if it set a single price. Claes Melander, 19701 30 Nonidentical consumer Profit max (consumer 1 demand) p = $10, & = $2450 п = $4900 (consumer 1 $2450, consumer 2 $2450) Profit max (consumer 2 demand) p = $10, & = $4050 п = $4050 (consumer 1 $0, consumer 2 $4050) Profit max (both consumers) p = $20, & = $1800 п = $5000 (consumer 1 $2400, consumer 2 $2600) Tie-in sales Allows customers to buy one product if they also promise to purchase another one Requirement tie-in sale Customer who buy one product from a firm are required to make all their purchases of another product from that firm Bundling (package tie-in sale) A firm sells only a bundle of two goods so that customers cannot buy either good separately. Paket (Bundling) Kund A är villig att betala 1000 kronor för Word och 600 kronor för Excel Kund B är villig att betala 600 för Word och 1000 kronor för Excel Antag att det inte är möjligt att sätta olika priser för de två kunderna Visa att Microsoft bör paketera Word+Excel Kund A Kund B Om pris är: Vinst Word 1000kr 600kr 1000kr 1000kr Excel 600kr 1000kr 1000kr 1000kr Paket 1600kr 1600kr 1600kr 3200kr Om både Word och Excel skulle kostat 1000kr skulle kund A inte köpa Excel och vice versa, alltså blir vinsten 2000kr (1000 för Word + 1000 för Excel) Om de paketeras tillsammans köper kunderna båda programmen, alltså blir vinsten 3200kr (1600 * två paket) 3200kr > 2000kr alltså bör Microsoft paketera sina produkter Claes Melander, 19701 31 Chapter 13 – Oligopoly and Monopolistic Competition Monopolistic Monopoly Oligopoly MR = MC MR = MC MR = MC p = MR = MC Ability to set price Price setter Price setter Price setter Price taker Market power p>MC p>MC p>MC p=MC Entry conditions No entry Limited entry Free entry Free entry Number of firms 1 Few Few or many Many Long-run profit ≥0 ≥0 0 0 Profit-maximization condition Strategy dependent on individual rival No (has no rivals) firms’ behavior Competition No (cares Yes Yes about market price only) Single May be May be product differentiated differentiated Local natural Automobile Plumbers in a gas utility manufacturers small town Products Example Competition Undifferentiated Apple farmers Game Theory The set of tools that economists use to analyze conflict and cooperation between firms Each oligopolistic and monopolistically competitive firm adopts a strategy to compete with other firms. Firms may use different strategies depending on whether they compete in a single-period game or in multiperiod games. Nash equilibrium (Oligopolistic equilibrium) No firm wants to change strategy given what everyone else is doing. Holding the strategies of all other players (firms) constant, no player can obtain a higher payoff by choosing a different strategy. Dominant strategy If one strategy strictly dominates (makes better profit) all other strategies, regardless of the actions chosen by rival firms, the firm should choose the dominate strategy Single-period game In a single period game none of the firms will cooperate to make higher joint profit when each firm has a substantial profit incentive to cheat on the agreement. We have a prisoners’ dilemma game. All players have dominant strategies that lead to a profit that is inferior to what they could achieve if they cooperated and pursued alternative strategies. Multiperiod games In a repeated game, a firm can influence its rival’s behavior by signaling and threatening to punish. Claes Melander, 19701 32 A firm will produce the output beneficial if both firms pursue it as long as the other firm follows (signaling) If the other firm cheats the collusion in period t, the firm can produce the less profitable output for both in a period t + 1 and all subsequent periods (threatening to punish) Cooperative oligopoly models Cartels If firms successfully collude, they produce the monopoly output and collectively earn the monopoly level of profit. Although their collective profits rise if all firms collude, each firm has an incentive to cheat on a cartel arrangement so as to raise its own profit even higher. For cartel prices to remain high, cartel members must be able to detect and prevent cheating, and noncartel firms must not be able to supply very much output. Laws against cartels When antitrust laws or competition policies prevent firms from colluding, firms may try to merge if permitted by law. Cournot model of noncooperative oligopoly Cournot equilibrium A Nash equilibrium, in which firms choose quantities, is also called a Cournot equilibrium: A set of quantities sold by firms such that, holding the quantities of all other firms constant, no firm can obtain a higher profit by choosing a different quantity. Q = 339 - p qA = Q(p) - qU = (339 - p) - qU p = 339 - qA - qU MRr = 339 - 2 qA - qU MRr = 339 - 2 qA - qU = 147 = MC qA = 96 - 0,5 qU qU = 96 - 0,5 qA qA = 96 - 0,5 (96 - 0,5 qA) P, $/pax qA = 64 qU = 64 P, $/pax 339 Monopoly Duopoly 339 211 243 147 MC 147 MC qU = 64 D MR 96 339 QA, Thousand American Airlines passengers per quarter Claes Melander, 19701 MRr 64 128 137,5 D Dr 275 QA, Thousand American Airlines passengers per quarter 33 339 Best-response Curve Show the output each firm picks to maximize its profit, give its belief about its rival’s output. The Cournot equilibrium occurs at the intersection of the best-response curves Deriving the Best-response curve If United sets MR = p its output is 192 (192 at y-axis) Americans best response (blue curve) will be 0 output other wise it will lose money. If United didn’t produce at all (0 at y-axis) Americans best response (blue curve) would be to produce 96 which will make them a monopoly profit. Stackelberg model of noncooperative behavior Much like the Cournot model but here one firm sets its output before the other firm, that firm is known as the Stackelberg leader, and the firm setting its price after is know as the Stackelberg follower. The leader will use its market position to manipulate the follower and make as large profit as possible. The leader will therefore choose an output where if the follower profit-maximize the leader will still make a larger profit. What output will the leader choose? Through the best-response curve the leader can estimate their rivals output at each output the firm produces. Using the best-response curve we can derive the residual demand for the leader. The leader will set its output where its residual marginal revenue is equal to its marginal cost. MRr = MC Government intervention A government may subsidize a domestic oligopoly firm so that it produces the Stackelberg leader quantity, which it sells in an international market. Such intervention has many problems and other government can retaliate causing loss of both countries. Claes Melander, 19701 34 Comparison of Collusive, Cournot, Stackelberg and Competitive Equilibria Monopoly qA 96 qU 0 Q = qA + qU 96 p $243 $9.2 A $0 U $9.2 = A + U Consumer surplus, CS $13.8 $13.8 Welfare, W = CS + Deadweight loss, DWL $4.6 Cartel 48 48 96 $243 $4.6 $4.6 $9.2 $4.6 $13.8 $4.6 Cournot 64 64 128 $211 $4.1 $4.1 $8.2 $8.2 $16.4 $2.0 Stackelberg 96 48 144 $195 $4.6 $2.3 $6.9 $10.4 $17.3 $1.2 Price Taking 96 96 192 $147 $0 $0 $0 $18.4 $18.4 $0 qU, Thousand United passengers per quarter American’s best-response curve Contract curve Price-taking equilibrium Cournot equilibrium Stackelberg equilibrium Cartel equilibrium United’s best-response curve qA, Thousand American passengers per quarter Claes Melander, 19701 35 Monopolistic Competition Two conditions hold in a monopolistically competitive equilibrium: MR = MC (firms set output to maximize profit) p = AC (new firms enter until no further profitable entry is possible) This shows that: the lower the fixed costs, the more firms there are in the monopolistically competitive equilibrium Monopolistic vs. competitive markets Firms in both markets make zero profits in the long-run. Competitive firms Horizontal residual demand curves Charge prices equal to marginal cost Monopolistically competitive firms Downward-sloping residual demand curves Charge prices above marginal cost Bertrand price-setting model In many oligopolistic or monopolistically competitive markets, firms set prices instead of quantities Bertrand equilibrium A Nash equilibrium, in which firms choose prices, is also called a Bertrand equilibrium: A set of prices such that no firm can obtain a higher profit by choosing a different price if the other firms continue to charge these prices. Identical products If the product is homogeneous and firms set prices, the Bertrand equilibrium price equals marginal cost. Bertrand vs. Cournot for identical products When firms produce identical products and have a constant marginal cost, the Cournot model is more plausible than the Bertrand. The latter model appears inconsistent with the real world. Therefore economists use the Cournot model to study market in which firms produce identical goods. Differentiated products If the products are differentiated, the Bertrand equilibrium price is above marginal cost. Typically, the markup of price over marginal cost is greater the more the goods are differentiated. Claes Melander, 19701 36 Chapter 14 – Strategy (OBS! Inte på tentan) Preventing entry: Simultaneous decissions Dominant strategy If it is more profitable to enter a market than staying out then the dominant strategy is entering Pure strategy The firm chooses an action with certainty Mixed strategy The firm chooses between its possible actions with given probabilities Simultaneous decision entry game If firms make simultaneous entry decisions, their actions depend on the market size and the possibility for success. If the market is large enough that two firms can make a profit, both enter. If only one firm can profitably produce, there are many possible Nash Equilibria. Preventing entry: Sequential decisions If an incumbent tries to prevent entry depends on: Does it pay for an incumbent to act to prevent entry? When can an incumbent prevent entry? What strategic acts and threats of future actions can an incumbent use to prevent entry? Does it pay to take action? Blockaded entry: Market conditions are such that no additional firm can profitably enter the market, even if the incumbent produces the monopoly output – so it is unnecessary for the incumbent to act strategically to prevent entry Deterred entry: The incumbent acts to prevent an additional firm from entering because it pays to do so Accommodated entry: Because it doesn’t pay for the incumbent to prevent entry through strategic action, it does nothing to prevent entry but reduces its output (or price) from monopoly to duopoly level to maximize its post-entry profit Credible threat An incumbent with first-mover advantage prevents entry by making a credible threat: It commits to taking an action (whether or not entry occurs) that lower potential entrant’s profit. Claes Melander, 19701 37 Commitment and Fixed Costs Which action the incumbent decides to pick depends on two key factors: the ability to commit and the entrants fixed costs. If the fixed cost is below the level where entry is blockaded the incumbent has following options: Cournot equilibrium: If the incumbent can’t commit – so both firms are on an equal footing – the incumbent produces the Cournot equilibrium quantity (No benefits compared to other actions, but an option) Stackelberg (accommodated-entry) equilibrium: If the incumbent can commit and the fixed cost of entry is relatively low, the incumbent commits to the Stackelberg leader quantity (larger than the Cournot quantity) Deterred-entry equilibrium: If the incumbent can commit and the fixed cost of entry is relatively high, it commits to a large enough quantity (larger than the Stackelberg) to deter entry. Cournot equ. Stackelberg equ. Deterred-entry equ. No Yes Yes Ability to commit High Entrants fixed cost Not important Low Conclusion: If the fixed cost is relatively low or zero, the incumbent commits to the Stackelberg leader quantity. If the fixed cost is relatively high, the incumbent commits to a larger output to deter entry Creating and Using Cost Advantages Lowering Marginal Cost while Raising Total Cost If a firm by investing in an expensive e.g. robotic arm for production; raises its total cost and lowers its marginal cost, the firm credibly commits to producing relatively large levels of output and thereby discourages entry. Thus firms benefit from lowering their marginal costs relative to those of rivals. Learning by Doing Firms may raise output in first period to be able to take advantages from the gained experience in future periods. Raising Rival’s Costs Direct Methods: By interfering with its rivals’ production or selling methods Indirect Methods: Incumbent firms may lobby for a government regulation that disproportionately affects new firms. Incumbent may buy up market supplies of scarce resources to prevent rivals from using them. Raising All Firms’ Costs There is always worth more to the monopoly to keep the entrant out than it is worth to the entrant to enter. Thus, raising all firms’ costs is worse for entrants than incumbents. Claes Melander, 19701 38 Advertising Monopoly Advertising A monopoly advertises to raise its profit A monopoly advertises only if it expects its net profit (gross profit minus the cost of advertising) to increase A monopoly sets advertises to the amount where Marginal Benefit equals Marginal Cost MB = MC (MB is the extra gross profit from one more units of advertising or the marginal revenue from one more unit of output) Strategic Advertising Advertising may either help or hurt rivals When advertising causes an increase in demand to rise for all firms in the market, your ad helps your rivals. Therefore rivals may cooperate to run advertising campaigns. When advertising differentiate your product from those of rivals it may benefit your firm at expense of your rivals, therefore hurting rivals Empirical Evidence Cigarette ads increases market demand, helps rivals Coca Cola ads gain from the ads at the expense of rivals, hurts rivals Saltine crackers lies in between these extremes Strategic Advertising Equilibria Whether ads hurts or helps rivals may affect the ad strategies that firms use. First Payoff Matrix: The Nash equilibrium is for both firms to advertise. This game is an example of a prisoners’ dilemma. Both would be better off if they colluded and agreed not to advertise Second Payoff Matrix: Advertising is a dominant strategy for both firms Ads Attracts New Customer to the Market Claes Melander, 19701 39 Chapter 18 – Externalities, Commons, and Public Goods Externalities An externality occurs when a consumer’s well-being or firm’s production capabilities are directly affected by the actions of other consumers or firms rather than indirectly through changes in prices. Negative externality Harms someone, consumers (people) and/or firms. E.g. A chemical plant that dumps its waste products into a lake, spoiling the lake’s beauty, harms a firm that rents boats for use on that waterway Positive externality Benefits others, consumers (people) and/or firms. E.g. By installing outdoor sculptures around its plant, a firm provides positive externalities to its neighbours. The inefficiency of competition with externalities Competitive firms and consumers do not have to pay (if not government regulated) for the harms of their negative externalities, therefore they do not calculate with the cost of negative externalities when they profit/utility maximize. Supply-and-Demand Analysis A competitive market produces excessive pollution because the firms’ private cost is less than their social cost. Private cost – The cost of production, not including externalities Social cost – The true cost which is the private cost plus the cost of the harms from externalities, e.g. pollution MKF – Marginal cost of pollution (the negative exernality) MKP – Private marginal cost MKS – Social marginal cost eS = Optimum equ. eC = Competitive equ. E = Deadweight loss By ignoring externality costs we do not maximize welfare Claes Melander, 19701 40 This diagram illustrates two main results: 1. A competitive market produces excessive negative externalities 2. The optimal amount of pollution is greater than zero Taxes If the government has sufficient information about demand, production cost and the harm of externality, it can use taxes or quotas to force the competitive market to produce the social optimum. Thus internalizing the externality for the firms. Conclusion It is usually optimal to have some negative externalities, because eliminating all of them requires eliminating desirable outputs and consumption activities as well. Market Structure and Externalities A monopoly sets its output where MR = MC, Competitive firms sets its output where MC = p With a negative externality, a non-competitive equilibrium may be closer to than a competitive equilibrium to the socially optimal equilibrium. A tax that increases the welfare for a competitive market, could in fact lower the welfare in a non-competitive market if output already was set lower than the optimal output Allocating Property Rights to Reduce Externalities Property right An exclusive privilege to use an asset Coase Theorem Externalities arise because property rights are not clearly defined. According to the Coase Theorem, allocating property rights to either of two parties results in an efficient outcome if the parties can bargain. If there are no impediments to bargaining, assigning property rights results in the efficient outcome at which joint profits are maximized Efficiency is achieved regardless of who receives the property rights Who gets the property rights affects income distribution. The property rights are valuable. The party without the property rights may be compensated by the other party Private Good Rivalry and Exclusion Claes Melander, 19701 41 Common Property/Good (Allmän egendom/ gemensamma resurer) Resources to which everyone has free access Common property resources are overexploited because Private MC < private MB Taxes and quotas may reduce or eliminate overuse Example o Roads – If too many drivers want to drive on the same road it leads to congestion (a negative externality) o Common pools – Petroleum and other fluids, first person who removes fluid from the pool gains ownership the good o Fisheries – The fish are accessible to all when they are in the water but as soon as someone catches them there someone property. The lack of clearly defined property rights leads to overfishing Public Goods (Kollektiva varor) A commodity or service whose consumption by one person does not prelude others from also consuming it (No Rivalry) Once a public good is provided to anyone, it can be provided to others at no additional cost. A public good produces a positive externality, and excluding anyone from consuming a public good is inefficient Public Goods often have a capacity roof, which if reached introduces rivalry e.g. A public swimming pool gets crowded. A Public good with rivalry can be seen as a Common good Public Goods without Exclusion (Rent kollektiva varor) A public good without a capacity roof that creates rivalry Example – National military defence, air Public Goods with Exclusion / Club Good (Klubbvara) A public good with exclusion As long as everyone pays there is no rivalry There is a capacity roof here as well Rivalry No Rivalry Exclusion Private Good: candy bar, pencil, aluminium foil Public good with exclusion: cable television, club good (concert, tennis club) No Exclusion Common-access resources: fishery, hunting, road Public good without exclusion: National defense, clean air Free Riding Many people are unwilling to pay for their share of a public good. They try to get others to pay for it, so they can free ride: benefit from the actions of others without paying. That is, they want to benefit from a positive externality Claes Melander, 19701 42 Chapter 19 – Asymmetric Information Problems due to Asymmetric Information Asymmetric information causes market failures when informed parties engage in opportunistic behaviour at the expense of uniformed parties. The resulting failures include the elimination of markets and pricing above marginal cost. Two types of problems arise from opportunism: Adverse selection Adverse selection is opportunism characterized by an informed person’s benefiting from trading or contracting with a less informed person who does not know about an unobserved characteristic of the informed person. Moral hazard Moral hazard is opportunism characterized by an informed person’s taking advantage of a less-informed person through an unobserved action. Differences between Adverse selection and Moral hazard Differences between unobserved characteristic and unobserved action E.g. George and Marge are going to get life insurances. Unknown to the company is that they skydive. George will skydive whether or not he has a life insurance o George’s unobserved characteristic leads to adverse selection for the comany Marge will skydive only if she has life insurance o Marge’s unobserved action is a moral hazard for the insurance company Responses to Adverse Selection To avoid adverse selection problems requires restricting the opportunistic behaviour or eliminating the information asymmetry (equalize information) Restricting the opportunistic behaviour A government can avoid adverse selection by providing insurance to everyone or by forcing everyone to buy insurance. Resulting in that not only the high risk people buy insurance and therefore spreading the risk for the insurance companies and lowers the adverse selection. Equalizing Information Screening – Uniformed people screen to determine the information of informed people or their products Signaling – Informed people send signals to uniformed people, or third parties such as the government or independent test centrals provide information How ignorance about quality drives out high-quality goods If consumers cannot distinguish between good and bad products before purchase, bad products may drive goods ones out of the market. This is a problem due to adverse selection. Claes Melander, 19701 43 Methods of dealing with this problem Laws to Prevent Opportunism – If there is a law saying that firms are liable to correct defective products, consumers don’t need worry about adverse selection Consumer Screening – Consumers may screen themselves or buy the information from objective experts, such as a mechanics to appraise a used car. Consumers may be affected by the firm’s reputation from other consumers or observation Standards and Certification – This way consumer can be sure that they receive a minimum quality level. Signaling by Firms – Though signals are only effective if the are credible. Some firms use brand name as a signal of quality. Others provide guarantees or warranties. Price Discrimination due to False Beliefs about Quality Firms can price discriminate by charging different prices to differently informed consumers. They charge more to the less in informed and vice versa. Same product, different brand name Firms can exploit ignorant customers by creating noise: selling virtually the same product under different brand names, charging a different price for each. Market Power from price ignorance If consumers don’t know how prices vary across firms, a firm can raise its price without losing all its customers. Thus if consumers have limited information about price, an equilibrium in which all firms charge the full-information competitive price is impossible and therefore gives them market power. Furthermore in this type of market where consumers have asymmetric information and when search costs and the number of firms are large, the only possible single-price equilibrium is at the monopoly price. Problems arising from ignorance when hiring Companies use signaling and screening to try to eliminate information asymmetries in hiring. Where prospective employees and firms share common interests – such as assigning the right worker to the right task – everyone benefits from eliminating the information asymmetry by having informed job candidates honestly tell the firms – through cheap talk – about their abilities. When two parties do not share common interests, cheap talk does not work. Potential employees may inform employers about their abilities by using expensive signals such as college degree. If these signals are unproductive (as when education serves only as a signal and provides no training), they may be privately beneficial but socially harmful. If the signals are productive (as when education provides training or leads to greater output due to more fitting job assignments), they may be both privately and socially beneficial. Firms may also screen. Job interviews, objective tests, and other screening devices that lead to a better matching of workers and jobs may be socially beneficial. Screening by statistical discrimination, however, is harmful to discriminated-against groups. Employers who Claes Melander, 19701 44 discriminate on the basis of a particular group characteristic may never learn that their discrimination is based on false beliefs because they never test these beliefs. Chapter 20 – Contracts and Moral Hazards Principal-Agent Problem A principal (employer) contracts with an agent (employee) to perform some task The profits made depends on the principal’s assets, the actions of the agent and the state of nature a a = number of hours, = random variable (e.g. weather), The principal’s assets = The actual equation Only agent dependent a Only State of nature dependent If the principal cannot observe the agent’s actions, the agent may engage in opportunistic behaviour. This moral hazard reduces the joint profit. An efficient contract leads to efficiency in production (joint profit is maximized by eliminating moral hazards) and efficiency risk bearing (the less-risk-averse party bears more of the risk). Risk averse – individual who don’t like bearing risk. Will pay preemie to be relived from the risk. Risk neutral – Individual who don’t mind bearing risk Types of contracts Fixed-fee contract – The payment to the principal is a fixed sum, F, and the agent receives the residual profit, a - F. There is also a possibility that the agent receives the fixed sum and vice versa. Hire contract – Two types, hourly rate (wage per hour) and piece rate (payment per unit sold). Principal’s residual profit is a - wa, where w is the wage per hour and a number of hours worked. Contingent contract – Payoff depend on the state of nature. One type is a splitting or sharing contract as in a house sale the estate agent charges a commission of 7 % on the sales price. Agent receives 0,07 a , Principal receives 0,93 a Production efficiency Production efficiency is achieved by maximizing the total or joint profit. Contract properties There has to be a large enough payoff for both parts to be willing to participate in the contract It has to be incentive compatible so that agent don’t engage in opportunistic behaviour An agent with a fixed-fee rental or profit-sharing contract gets the entire marginal profit and produces optimally without monitoring. Claes Melander, 19701 45 Contract Fixed-fee rental contract Rent (to principal) Hire contract, per unit pay Pay equals marginal cost Pay is greater than marginal cost Contingent contract Share revenue Share profit Full Information Production Efficiency Asymmetric Information Production Moral Hazard Efficiency Problem Yes Yes No Noa Noc Nob No Yes Yes No Yes Nob Nob Yes Yes a The agent may not participate and has no incentive to sell the optimal number of goods. Efficiency can be achieved only is the principal supervises. b Unless the agent steals all the revenue (or profit) from extra sale, inefficiency results. c The agent sells too many or the principal directs the agent to sell too few goods. Trade-off between efficiency in production and in risk bearing Usually a contract does not achieve efficiency in production and in risk bearing. A principal and an agent may agree to contract that strikes a balance between reducing moral hazards and allocating risk optimally. Contracts that eliminate moral hazards require the agent to bear the risk. If the agent is more risk averse than the principal, the parties may trade off a reduction in production efficiency to lower risk for the agent. Payments linked to production and profit To reduce shirking, employers may reward employees for greater individual or group productivity. Paying employees by piece (output produced) instead of time (hours worked) is proven to be effective but not practical in all markets. Three problems with Piece Rates Measuring output Eliciting the desired behavior Persuading workers to accept piece rates Piece rates are normally used for low-paying industries. Another incentive scheme is needed for managers, corporate directors and others whose productivity is difficult to quantify, especially those who work as part of a team. Year-end bonus – A lump-sum based on the firm’s performance or that group of workers within the firm Stock options – (Options program), blir värdefulla om företagets aktie går bra annars blir optionerna värdelösa då inlösedagen kommer. Claes Melander, 19701 46 Monitoring Because of asymmetric information an employers must normally monitor workers’ efforts to prevent shirking. Less monitoring is necessary as the employee’s interest in keeping the job increases. The employer may require the employee to post a large bond that is forfeited if the employee is caught shirking, stealing, or otherwise misbehaving. If an employee cannot afford to post a bond the employer may use deferred payments or efficiency wages – unusually high wages – to make it worthwhile for the employee to keep the job. Checks on principals Often both agents and principals can engage in opportunistic behavior. If a firm must reveal its actions to its employees, it is less likely to be able to take advantage of the employees. To convey information, an employer may let employees participate in decision-making meetings or audit the company’s books. Alternatively, an employer may make commitments so that it is in the employer’s best interest to tell employees the truth. These commitments, such as laying off workers rather than reducing wages during downturns, may reduce moral hazards but lead to nonoptimal production. Contract choice A principal may be able to obtain valuable information from an agent by offering a choice of contracts. Employers avoid moral hazard problems by preventing adverse selection. For example, they may present potential employees with a choice of contracts, prompting hardworking job applicants to choose one contract and lazy candidates to choose another. Chapter 15.4 – Vertical integration Vertically integration – participate in more than one successive stage of the production or distribution of goods or services Quasi-vertically integrate – use contracts or other means to control firms with which is has vertical relation A firm may vertically integrate or buy from a factor market. Depending on which is more profitable, a firm vertically integrates and produces input itself or buys the input from others. Because vertical integration is costly, firms integrate only if there are significant benefits. Possible Benefits with vertical integration Lowering transaction costs Ensuring a steady supply Avoiding government restrictions Extending market power to another market Eliminating market power of rivals Claes Melander, 19701 47