Carriage of goods by sea

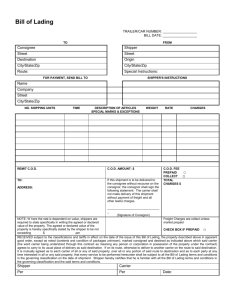

advertisement