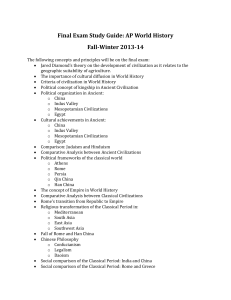

Course Overview

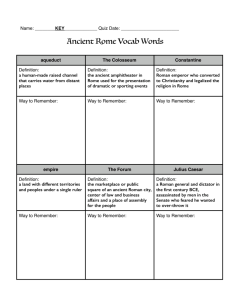

advertisement