The Legend of the Trojan War - Northview Junior Classical League

advertisement

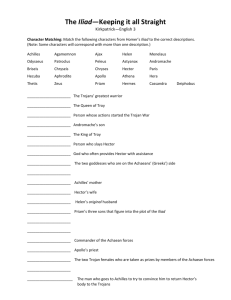

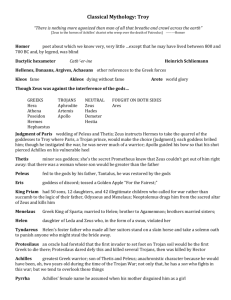

The Legend of the Trojan War [This document is in the public domain and thus may be used by anyone, in whole or in part, without permission and without charge, provided the source is acknowledged, released May 1999] [Note: This summary, which has been prepared by Ian Johnston of Malaspina University-College, Nanaimo, BC, for students in Classics 101 and Liberal Studies, is a brief account of a number of different old stories about the Trojan war, arranged in more or less chronological sequence. There are several different, even contradictory, versions of events. There is no one authoritative narrative of the whole war. Many of these stories were obviously current before Homer, and the story continued to be embellished by the Romans and Medieval writers] 1. The gods Apollo and Poseidon, during a time when they were being punished by having to work among men, built the city of Troy for Priam's father, Laomedon. They invited the mortal man Aeacus (the son of Zeus and Aegina and grandfather of Achilles) to help them, since destiny had decreed that Troy would one day be captured in a place built by human hands (so a human being had to help them). 2. When newly constructed, Troy was attacked and captured by Herakles (Hercules), Telamon (brother of Peleus and therefore the uncle of Achilles and father of Telamonian Ajax and Teucros), and Peleus (son of Aeacus and father of Achilles), as a punishment for the fact that Laomedon had not given Hercules a promised reward of immortal horses for rescuing Laomedon's daughter Hesione. Telamon killed Laomedon and took Hesione as a concubine (she was the mother of Teucros). 3. Priam, King of Troy and son of Laomedon, had a son from his wife Hekabe (or Hecuba), who dreamed that she had given birth to a flaming torch. Cassandra, the prophetic daughter of Priam, foretold that the new-born son, Paris (also called Alexandros or Alexander), should be killed at birth or else he would destroy the city. Paris was taken out to be killed, but he was rescued by shepherds and grew up away from the city in the farms by Mount Ida. As a young man he returned to Troy to compete in the athletic games, was recognized, and returned to the royal family. 4. Peleus (father of Achilles) fell in love with the sea nymph Thetis, whom Zeus, the most powerful of the gods, also had designs upon. But Zeus learned of an ancient prophecy that Thetis would give birth to a son greater than his father, so he gave his divine blessing to the marriage of Peleus, a mortal king, and Thetis. All the gods were invited to the celebration, except, by a deliberate oversight, Eris, the goddess of strife. She came anyway and brought a golden apple, upon which was written "For the fairest." Hera (Zeus's wife), Aphrodite (Zeus's daughter), and Athena (Zeus's daughter) all made a claim for the apple, and they appealed to Zeus for judgment. He refused to adjudicate a beauty contest between his wife and two of his daughters, and the task of choosing a winner fell to Paris (while he was still a herdsman on Mount Ida, outside Troy). The goddesses each promised Paris a wonderful prize if he would pick her: Hera offered power, Athena offered military glory and wisdom, and Aphrodite offered him the most beautiful woman in the world as his wife. In the famous Judgement of Paris, Paris gave the apple to Aphrodite. 5. Helen, daughter of Tyndareus and Leda, was also the daughter of Zeus, who had made love to Leda in the shape of a swan (she is the only female child of Zeus and a mortal). Her beauty was famous throughout the world. Her father Tyndareus would not agree to any man's marrying her, until all the Greeks warrior leaders made a promise that they would collectively avenge any insult to her. When the leaders made such an oath, Helen then married Menelaus, King of Sparta. Her twin (non-divine) sister Klytaimnestra (Clytaemnestra), born at the same time as Helen but not a daughter of Zeus, married Agamemnon, King of Argos, and brother of Menelaus. Agamemnon was the most powerful leader in Hellas (Greece). 6. Paris, back in the royal family at Troy, made a journey to Sparta as a Trojan ambassador, at a time when Menelaus was away. Paris and Helen fell in love and left Sparta together, taking with them a vast amount of the city's treasure and returning to Troy via Cranae, an island off Attica, Sidon, and Egypt, among other places. The Spartans set off in pursuit but could not catch the lovers. When the Spartans learned that Helen and Paris were back in Troy, they sent a delegation (Odysseus, King of Ithaca, and Menelaus, the injured husband) to Troy demanding the return of Helen and the treasure. When the Trojans refused, the Spartans appealed to the oath which Tyndareus had forced them all to take (see 5 above), and the Greeks assembled an army to invade Troy, asking all the allies to meet in preparation for embarkation at Aulis. Some stories claimed that the real Helen never went to Troy, for she was carried off to Egypt by the god Hermes, and Paris took her double to Troy. 7. Achilles, the son of Peleus and Thetis, was educated as a young man by Chiron, the centaur (half man and half horse). One of the conditions of Achilles's parents' marriage (the union of a mortal with a divine sea nymph) was that the son born to them would die in war and bring great sadness to his mother. To protect him from death in battle his mother bathed the infant in the waters of the river Styx, which conferred invulnerability to any weapon. And when the Greeks began to assemble an army, Achilles's parents hid him at Scyros disguised as a girl. While there he met Deidameia, and they had a son Neoptolemos (also called Pyrrhus). Calchas, the prophet with the Greek army, told Agamemnon and the other leaders that they could not conquer Troy without Achilles. Odysseus found Achilles by tricking him; Odysseus placed a weapon out in front of the girls of Scyros, and Achilles reached for it, thus revealing his identity. Menoitios, a royal counsellor, sent his son Patroclus to accompany Achilles on the expedition as his friend and advisor. 8. The Greek fleet of one thousand ships assembled at Aulis. Agamemnon, who led the largest contingent, was the commander-inchief. The army was delayed for a long time by contrary winds, and the future of the expedition was threatened as the forces lay idle. Agamemnon had offended the goddess Artemis by an impious boast, and Artemis had sent the winds. Finally, in desperation to appease the goddess, Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigeneia. Her father lured her to Aulis on the pretext that she was to be married to Achilles (whose earlier marriage was not known), but then he sacrificed her on the high altar. One version of her story claims that Artemis saved her at the last minute and carried her off to Tauris where she became a priestess of Artemis in charge of human sacrifices. While there, she later saved Orestes and Pylades. In any case, after the sacrifice Artemis changed the winds, and the fleet sailed for Troy. 9. On the way to Troy, Philoctetes, the son of Poeas and leader of the seven ships from Methone, suffered a snake bite when the Greeks landed at Tenedos to make a sacrifice. His pain was so great and his wound so unpleasant (especially the smell) that the Greek army abandoned him against his will on the island. 10. The Greek army landed on the beaches before Troy. The first man ashore, Protesilaus, was killed by Hector, son of Priam and leader of the Trojan army. The Greeks sent another embassy to Troy, seeking to recover Helen and the treasure. When the Trojans denied them, the Greek army settled down into a siege which lasted many years. 11. In the tenth year of the war (where the narrative of the Iliad begins), Agamemnon insulted Apollo by taking as a slave-hostage the girl Chryseis, the daughter of Chryses, a prophet of Apollo, and refusing to return her when her father offered compensation. In revenge, Apollo sent nine days of plague down upon the Greek army. Achilles called an assembly to determine what the Greeks should do. In that assembly, he and Agamemnon quarrelled bitterly, Agamemnon confiscated from Achilles his slave girl Briseis, and Achilles, in a rage, withdrew himself and his forces (the Myrmidons) from any further participation in the war. He asked his mother, Thetis, the divine sea nymph, to intercede on his behalf with Zeus to give the Trojans help in battle, so that the Greek forces would recognize how foolish Agamemnon had been to offend the best soldier under his command. Thetis made the request of Zeus, reminding him of a favour she had once done for him, warning him about a revolt against his authority, and he agreed. 12. During the course of the war, numerous incidents took place, and many died on both sides. Paris and Menelaus fought a duel, and Aphrodite saved Paris just as Menelaus was about to kill him. Achilles, the greatest of the Greek warriors, slew Cycnus, Troilus, and many others. He also, according to various stories, was a lover of Patroclus, Troilus, Polyxena, daughter of Priam, Helen, and Medea. Odysseus and Diomedes slaughtered thirteen Thracians (Trojan allies) and stole the horses of King Rhesus in a night raid. Telamonian Ajax (the Greater Ajax) and Hector fought a duel with no decisive result. A common soldier, Thersites, challenged the authority of Agamemnon and demanded that the soldiers abandon the expedition. Odysseus beat Thersites into obedience. In the absence of Achilles and following Zeus's promise to Thetis (see 11), Hector enjoyed great success against the Greeks, breaking through their defensive ramparts on the beach and setting the ships on fire. 13. While Hector was enjoying his successes against the Greeks, the latter sent an embassy to Achilles, requesting him to return to battle. Agamemnon offered many rewards in compensation for his initial insult (see 11). Achilles refused the offer but did say that he would reconsider if Hector ever reached the Greek ships. When Hector did so, Achilles's friend Patroclus (see 7) begged to be allowed to return to the fight. Achilles gave him permission, advising Patroclus not to attack the city of Troy itself. He also gave Patroclus his own suit of armour, so that the Trojans might think that Achilles had returned to the war. Patroclus resumed the fight, enjoyed some dazzling success (killing one of the leaders of the Trojan allies, Sarpedon from Lykia), but he was finally killed by Hector, with the help of Apollo. 14. In his grief over the death of his friend Patroclus, Achilles decided to return to the battle. Since he had no armour (Hector had stripped the body of Patroclus and had put on the armour of Achilles), Thetis asked the divine artisan Hephaestus, the crippled god of the forge, to prepare some divine armour for her son. Hephaestus did so, Thetis gave the armour to Achilles, and he returned to the war. After slaughtering many Trojans, Achilles finally cornered Hector alone outside the walls of Troy. Hector chose to stand and fight rather than to retreat into the city, and he was killed by Achilles, who then mutilated the corpse, tied it to his chariot, and dragged it away. Achilles built a huge funeral pyre for Patroclus, killed Trojan soldiers as sacrifices, and organized the funeral games in honour of his dead comrade. Priam travelled to the Greek camp to plead for the return of Hector's body, and Achilles relented and returned it to Priam in exchange for a ransom. 15. In the tenth year of the war the Amazons, led by Queen Penthesilea, joined the Trojan forces. She was killed in battle by Achilles, as was King Memnon of Ethiopa, who had also recently reinforced the Trojans. Achilles's career as the greatest warrior came to an end when Paris, with the help of Apollo, killed him with an arrow which pierced him in the heel, the one vulnerable spot, which the waters of the River Styx had not touched because his mother had held him by the foot (see 7) when she had dipped the infant Achilles in the river. Telamonian Ajax, the second greatest Greek warrior after Achilles, fought valiantly in defense of Achilles's corpse. At the funeral of Achilles, the Greeks sacrificed Polyxena, the daughter of Hecuba, wife of Priam. After the death of Achilles, Odysseus and Telamonian Ajax fought over who should get the divine armour of the dead hero. When Ajax lost the contest, he went mad and committed suicide. In some versions, the Greek leaders themselves vote and decide to award the armour to Odysseus. 16. The Greeks captured Helenus, a son of Priam, and one of the chief prophets in Troy. Helenus revealed to the Greeks that they could not capture Troy without the help of Philoctetes, who owned the bow and arrows of Hercules and whom the Greeks had abandoned on Tenedos (see 9 above). Odysseus and Neoptolemus (the son of Achilles) set out to persuade Philoctetes, who was angry at the Greeks for leaving him alone on the island, to return to the war, and by trickery they succeeded. Philoctetes killed Paris with an arrow shot from the bow of Hercules. 17. Odysseus and Diomedes ventured into Troy at night, in disguise, and stole the Palladium, the sacred statue of Athena, which was supposed to give the Trojans the strength to continue the war. The city, however, did not fall. Finally the Greeks devised the strategy of the wooden horse filled with armed soldiers. It was built by Epeius and left in front of Troy. The Greek army then withdrew to Tenedos (an island off the coast), as if abandoning the war. Odysseus went into Troy disguised, and Helen recognized him. But he was sent away by Hecuba, the wife of Priam, after Helen told her. The Greek soldier Sinon stayed behind when the army withdrew and pretended to the Trojans that he had deserted from the Greek army because he had information about a murder Odysseus had committed. He told the Trojans that the horse was an offering to Athena and that the Greeks had built it to be so large that the Trojans could not bring it into their city. The Trojan Laocoon warned the Trojans not to believe Sinon ("I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts"); in the midst of his warnings a huge sea monster came from the surf and killed Laocoon and his sons. 18. The Trojans determined to get the Trojan Horse into their city. They tore down a part of the wall, dragged the horse inside, and celebrated their apparent victory. At night, when the Trojans had fallen asleep, the Greek soldiers hidden in the horse came out, opened the gates, and gave the signal to the main army which had been hiding behind Tenedos. The city was totally destroyed. King Priam was slaughtered at the altar by Achilles's son Neoptolemos. Hector's infant son, Astyanax, was thrown off the battlements. The women were taken prisoner: Hecuba (wife of Priam), Cassandra (daughter of Priam), and Andromache (wife of Hector). Helen was returned to Menelaus. 19. The gods regarded the sacking of Troy and especially the treatment of the temples as a sacrilege, and they punished many of the Greek leaders. The fleet was almost destroyed by a storm on the journey back. Menelaus's ships sailed all over the sea for seven years— to Egypt (where, in some versions, he recovered his real wife in the court of King Proteus—see 6 above). Agamemnon returned to Argos, where he was murdered by his wife Clytaemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus. Cassandra, whom Agamemnon had claimed as a concubine after the destruction of Troy, was also killed by Clytaemnestra. Aegisthus was seeking revenge for what the father of Agamemnon (Atreus) had done to his brother (Aegisthus' father) Thyestes. Atreus had given a feast for Thyestes in which he fed to him the cooked flesh of his own children (see the family tree of the House of Atreus given below). Clytaemnestra claimed that she was seeking revenge for the sacrifice of her daughter Iphigeneia (see 8 above). 20. Odysseus (called by the Romans Ulysses) wandered over the sea for many years before reaching home. He started with a number of ships, but in a series of misfortunes, lasting ten years because of the enmity of Poseidon, the god of the sea, he lost all his men before returning to Ithaca alone. His adventures took him from Troy to Ismareos (land of the Cicones); to the land of the Lotos Eaters, the island of the cyclops (Poseidon, the god of the sea, became Odysseus's enemy when Odysseus put out the eye of Polyphemus, the cannibal cyclops, who was a son of Poseidon); to the cave of Aeolos (god of the winds), to the land of the Laestrygonians, to the islands of Circe and Calypso, to the underworld (where he talked to the ghost of Achilles); to the land of the Sirens, past the monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis, to the pastures of the cattle of Helios, the sun god, to Phaiacia. Back in Ithaca in disguise, with the help of his son Telemachus and some loyal servants, he killed the young princes who had been trying to persuade his wife, Penelope, to marry one of them and who had been wasting the treasure of the palace and trying to kill Telemachus. Odysseus proved who he was by being able to string the famous bow of Odysseus, a feat which no other man could manage, and by describing for Penelope the secret of their marriage bed, that Odysseus had built it around an old olive tree. 21. After the murder of Agamemnon by his wife Clytaemnestra (see 19 above), his son Orestes returned with a friend Pylades to avenge his father. With the help of his sister Electra (who had been very badly treated by her mother, left either unmarried or married to a poor farmer so that she would have no royal children), Orestes killed his mother and Aegisthus. Then he was pursued by the Furies, the goddesses of blood revenge. Suffering fits of madness, Orestes fled to Delphi, then to Tauri, where, in some versions, he met his long-lost sister, Iphigeneia. She had been rescued from Agamemnon's sacrifice by the gods and made a priestess of Diana in Tauri. Orestes escaped with Iphigeneia to Athens. There he was put on trial for the matricide. Apollo testified in his defense. The jury vote was even; Athena cast the deciding vote in Orestes's favour. The outraged Furies were placated by being given a permanent place in Athens and a certain authority in the judicial process. They were then renamed the Eumenides (The Kindly Ones). Orestes was later tried for the same matricide in Argos, at the insistence of Tyndareus, Clytaemnestra's father. Orestes and Electra were both sentenced to death by stoning. Orestes escaped by capturing Helen and using her as a hostage. 22. Neoptolemus, the only son of Achilles, married Hermione, the only daughter of Helen and Menelaus. Neoptolemus also took as a wife the widow of Hector, Andromache. There was considerable jealously between the two women. Orestes had wished to marry Hermione; by a strategy he arranged it so that the people of Delphi killed Neoptolemus. Then he carried off Hermione and married her. Menelaus tried to kill the son of Neoptolemus, Molossus, and Andromache, but Peleus, Achilles's father, rescued them. Andromache later married Helenus. Orestes's friend Pylades married Electra, Orestes sister. 23. Aeneas, the son of Anchises and the goddess Aphrodite and one of the important Trojan leaders in the Trojan War, fled from the city while the Greeks were destroying it, carrying his father, Anchises, his son Ascanius, and his ancestral family gods with him. Aeneas wandered all over the Mediterranean. On his journey to Carthage, he had an affair with Dido, Queen of Carthage. He abandoned her without warning, in accordance with his mission to found another city. Dido committed suicide in grief. Aeneas reached Italy and there fought a war against Turnus, the leader of the local Rutulian people. He did not found Rome but Lavinium, the main centre of the Latin league, from which the people of Rome sprang. Aeneas thus links the royal house of Troy with the Roman republic. The Cultural Influence of the Legend of the Trojan War No story in our culture, with the possible exception of the Old Testament and the story of Jesus Christ, has inspired writers and painters over the centuries more than the Trojan War. It was the fundamental narrative in Greek education (especially in the version passed down by Homer, which covers only a small part of the total narrative), and all the tragedians whose works survive wrote plays upon various aspects of it, and these treatments, in turn, helped to add variations to the traditional story. No one authoritative work defines all the details of the story outlined above. Unlike the Old Testament narratives, which over time became codified in a single authoritative version, the story of the Trojan War exists as a large collection of different versions of the same events (or parts of them). The war has been interpreted as a heroic tragedy, as a fanciful romance, as a satire against warfare, as a love story, as a passionately anti-war tale, and so on. Just as there is no single version which defines the "correct" sequence of events, so there is no single interpretative slant on how one should understand the war. Homer's poems enjoyed a unique authority, but they tell only a small part of the total story. The following notes indicate only a few of the plays, novels, and poems which have drawn on and helped to shape this ancient story. 1. The most famous Greek literary stories of the war are Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, our first two epic poems, composed for oral recitation probably in the eighth century before Christ. The theme of the Iliad is the wrath of Achilles at the action of Agamemnon, and the epic follows the story of Achilles's withdrawal from the war and his subsequent return (see paragraphs 11, 12, 13, and 14 above). The Odyssey tells the story of the return of Odysseus from the war (see 20 above). A major reason for the extraordinary popularity and fecundity of the story of the Trojan War is the unquestioned quality and authority of these two great poems, even though they tell only a small part of the total narrative and were for a long time unavailable in Western Europe (after they were lost to the West, they did not appear until the fifteenth century). The Iliad was the inspiration for the archaeological work of Schliemann in the nineteenth century, a search which resulted in the discovery of the site of Troy at Hissarlik, in modern Turkey. 2. The Greek tragedians, we know from the extant plays and many fragments, found in the story of the Trojan War their favorite material, focusing especially on the events after the fall of the city. Aeschylus's famous trilogy, The Oresteia (Agamemnon, Choephoroi [Libation Bearers], and Eumenides [The Kindly Ones]), tells of the murder of Agamemnon and Cassandra by Clytaemnestra and Aegisthus, the revenge of Orestes, and the trial for the matricide. Both Sophocles and Euripides wrote plays about Electra, and Euripides also wrote a number of plays based on parts the larger story: The Trojan Women, The Phoenissae, Orestes, Helen, and Iphigeneia in Tauris (see 21 and 22 above). Sophocles also wrote Philoctetes (see 16) and Ajax (see 15) on events in the Trojan War. 3. Greek philosophers and historians used the Trojan War as a common example to demonstrate their own understanding of human conduct. So Herodotus and Thucydides, in defining their approach to the historical past, both offer an analysis of the origins of the war. Plato's Republic uses many parts of Homer's epics to establish important points about political wisdom (often citing Homer as a negative example). Alexander the Great carried a copy of the Iliad around with him in a special royal casket which he had captured from Darius, King of the Persians. 4. The Romans also adopted the story. Their most famous epic, Virgil's Aeneid, tells the story of Aeneas (see 23). And in the middle ages, the Renaissance, and right up to the present day, writers have retold parts of the ancient story. These adaptations often make significant changes in the presentation of particular characters, notably Achilles, who in many versions becomes a knightly lover, and Odysseus/Ulysses, who is often a major villain. Ulysses) and Diomedes appear in Dante's Inferno. Of particular note are Chaucer's and Shakespeare's treatments of the story of Troilus and Cressida. Modern writers who have drawn on the literary tradition of this ancient cycle of stories include Sartre (The Flies), O'Neill (Mourning Becomes Electra), Giradoux (Tiger at the Gates), Joyce (Ulysses), Eliot, Auden, and many others. In addition, the story has formed the basis for operas and ballets, and the story of Odysseus has been made into a mini-series for television. This tradition is a complicated one, however, because many writers, especially in Medieval times, had no direct knowledge of the Greek sources and re-interpreted the details in very non-Greek ways (e.g., Dante, Chaucer, and Shakespeare). Homer's text, for example, was generally unknown in Western Europe until the late fifteenth century. 5. For the past two hundred years there has been a steady increase in the popularity of Homer's poems (and other works dealing with parts of the legend) translated into English. Thus, in addition to the various modern adaptations of parts of the total legend of the Trojan war (e.g., Brad Pitt's Troy), the ancient versions are still very current. The Royal House of Atreus The most famous (or notorious) human family in Western literature is the House of Atreus, the royal family of Mycenae. To follow the brief outline below, consult the simplified family tree in p. 279 of the text of Aeschylus's play. Note that different versions of the story offer modifications of the family tree. The family of Atreus suffered from an ancestral crime, variously described. Most commonly Tantalus, son of Zeus and Pluto, stole the food of the gods. In another version he kills his son Pelops and feeds the flesh to the gods (who later, when they discover what they have eaten, bring Pelops back to life). Having eaten the food of the gods, Tantalus is immortal and so cannot be killed. In Homer's Odyssey, Tantalus is punished everlastingly in the underworld. The family curse originates with Pelops, who won his wife Hippodamia in a chariot race by cheating and betraying and killing his co-conspirator (who, as he was drowning, cursed the family of Pelops). The curse blighted the next generation: the brothers Atreus and Thyestes quarrelled. Atreus killed Thyestes's sons and served them to their father at a reconciliation banquet. To obtain revenge, Thyestes fathered a son on his surviving child, his daughter Pelopia. This child was Aegisthus, whose task it was to avenge the murder of his brothers. When Agamemnon set off for Troy (sacrificing his daughter Iphigeneia so that the fleet could sail from Aulis), Aegisthus seduced Clytaemnestra and established himself as a power in Argos. When Agamemnon returned, Clytaemnestra and Aegisthus killed him (and his captive Cassandra)--Aegisthus in revenge for his brothers, Clytaemnestra in revenge for the sacrifice of Iphigeneia. Orestes at the time was away, and Electra had been disgraced. Orestes returned to Argos to avenge his father. With the help of a friend, Pylades, and his sister Electra, he succeeded by killing his mother, Clytaemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus. After many adventures (depending upon the narrative) he finally received absolution for the matricide, and the curse was over. Many Greek poets focused on this story. Homer repeatedly mentions the murder of Agamemnon in the Odyssey and the revenge of Orestes on Aegisthus (paying no attention to the murder of Clytaemnestra); Aeschylus's great trilogy The Oresteia is the most famous classical treatment of the tale; Sophocles and Euripides both wrote plays on Orestes and Electra. One curious note is the almost exact parallel between the story of Orestes in this family tale and the story of Hamlet. These two stories arose, it seems, absolutely independently of each other, and yet in many crucial respects are extraordinarily similar. This match has puzzled many a comparative literature scholar and invited all sorts of psychological theories about the trans-cultural importance of matricide as a theme.