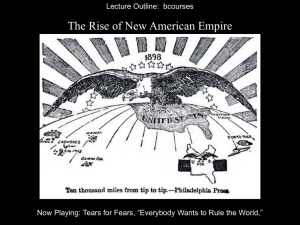

Department of History

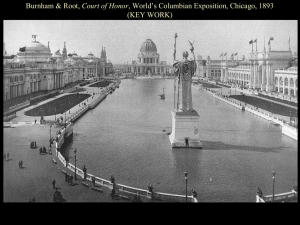

advertisement