The_first_three_years_GOchiltree_Jun99(reformatted)

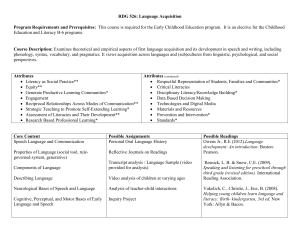

advertisement