Chapter 4

advertisement

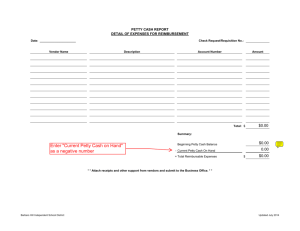

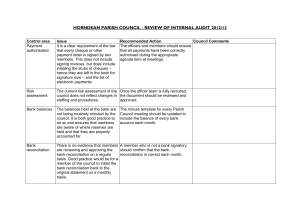

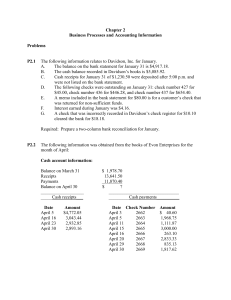

Chapter 4 Chapter 4 Financial Management A. Financial Reporting to Members & Board, and to the National (Treasurer's Report) The most fundamental of an officer's fiduciary duties to the rest of the Board and to the membership and the National office is to report on the chapter's finances, accurately and timely. Most by-laws require the Treasurer to submit reports to the Board and the membership. Those reports, if properly designed, can be used to transmit information that will be needed for other purposes as well. The National office needs to be made sufficiently aware of each chapter's financial transactions that it can perform its responsibility to monitor the activities of those covered by the group exemption and certify accurately to the IRS on an annual basis that all are still operating within exempt purposes. Chapter financial reports should report the essential data that will be asked at year-end on the chapter's own Form 990-EZ or 990 filing, or the group 990 filing, if the chapter elects to participate in that. In addition to quantitative figures, a number of qualitative questions are asked on those forms. See the appendices to Chapter 5 to view the IRS forms. In the appendix to this chapter (Chapter 4) is one suggested format for a Treasurer's report that both supplies much of the necessary 990 information as well as tying down the cash accounts to the bank reconciliation. B. Records Retention A chapter's organizing documents, meeting minutes, insurance policies (even expired ones), and its essential financial records should be retained indefinitely. Essential financial records would include all final financial statements (balance sheet and income or profit & loss statements), the general ledger, which is the organization's "books", and all income tax return filings. There are many suggested periods of retention of other categories of records. One standard set of suggestions, not tailored for non-profits but for businesses in general, is displayed in the appendix to this chapter. The suggested retention periods are generally geared to the statutes of limitations for enforcement of various business and tax laws, federal and state. C. Bank Reconciliations (sample format) 1 Chapter 4 The best single step to protect both financial integrity and accuracy is perform timely, monthly reconciliation of the bank accounts to the chapter's "books," which ultimately means its financial statements, including the Treasurer's report. The reconciliation process should involve more than one single person. At a minimum, a second responsible person should review them on a timely basis, which means at least within the same month. It is probably not an exaggeration to say that half of the small non-profit organization financial frauds of recent years could have been avoided if the full reconciliation process had been performed timely. Fraud aside, bank reconciliation is one of the best protection methods against honest mistakes, either on the part of the chapter or the part of the bank. The process of reconciliation does not differ from reconciling your own individual account to the running balance in your check register. The cash line item in the chapter's general ledger functions as the check register. There are many acceptable reconciliation formats, including the forms that are often imprinted on the back of bank statements. All involve explaining to the penny the difference between the balance that the bank reports as of cutoff day, and the balance reported in the organization's books and records. One suggested format appears in the appendix to this chapter. D. Authorized Signatories on Accounts If at all practical, the only authorized signatories should be responsible officers. It is good policy to require two signatures on checks above a certain amount, such as $500 or $1,000. Check-signing machines should not be used at all by chapters, even if they are theoretically kept locked. The addressee to receive monthly bank statements should be a responsible officer, and if at all possible, it should be someone other than the person who initiates check disbursements. Ideally, the person who receives the bank statement should be the one who reconciles it to the books of account maintained by someone else, but this is often impractical. If the person who receives the statements at least opens them and looks through the contents with a critical eye, asking questions of financial personnel about any items that appear unusual, the chances for financial fraud will be greatly reduced. E. Depositing Receipts It is absolutely good practice to deposit checks (and cash even more so) as quickly as possible. Although it may not be practical to make bank deposits on every day an item of income is received, in no case should large checks be left unlocked overnight, and in no case should any receipts be left undeposited for more than a week. The risk of loss or defalcation is too great. It is also virtually imperative that the bank account be reconciled on a monthly basis, within the month it is received. It is very good practice for the reconciliation to be 2 Chapter 4 performed by someone other than the person primarily responsible for depositing checks. F. Petty Cash Funds The use of petty cash funds is to be discouraged. They are notorious sources of loss through misplacement and petty theft. They also make for poor accounting records, since a petty cash voucher, even if it is filled out, usually does not provide enough detail to determine how the expenditure should be classified. Petty cash voucher forms almost always have a line for the initials or signature of authorization from a responsible official other than the one receiving the funds, but this step is often ignored. Also, petty cash records are no substitute for the kinds of substantiation required for reimbursed business expenses. See Chapter 3, section E, concerning those requirements. If a petty cash disbursement constitutes a permanent reimbursement for an expense incurred, the full accounting for that expense should still be made on an expense reimbursement form, with the required receipts attached. It is not unreasonable to expect volunteer leaders to advance expenses from their own pockets, submit full expense reports for reimbursement, and wait a week or more to receive a fully authorized reimbursement check. Travel advances are to be discouraged, since they may stand unaccounted for a long time, which creates problems of the appearance of unauthorized loans and deemed taxable compensation. Under some circumstances, short-term travel advances relating to specific trips are necessary. If the chapter's financial policies permit such advances, they should be either accounted for or restored to the organization as quickly as possible after each trip. G. Budgeting Most people see the advantages of having the Board approve budgets in advance of each year and each monetarily large event or undertaking. The advantages are the preservation of the chapter's financial soundness and the step of gaining Board authorization for overall levels and categories of expenditures, within which operating officers may exercise day to day authority over specific expenditures. There is an additional advantage to budgeting that many people do not see. Namely, it is one of the better forms of protection against fraud and misappropriation. Fraudulent disbursements (or fraudulent failure to deposit receipts) very often show up early on through comparison of financial line items to budgets and to past periods. Budgets need not be overly elaborate. They should specify an amount for each revenue and expense line item or category for which the chapter keeps records (see the suggested Treasurer's Report format in the appendix to this chapter.) They should be derived by estimates that are based first on prior history, and then on known commitments, contracts and leases. 3 Chapter 4 Budgeting, which simply involves estimating and projecting receipts and expenditures is not a science, it is an art form. The only rule of thumb is to gather as much objective information as possible, and to break estimates and projections down into smaller periods and smaller categories, avoiding the temptation to make large, overall guesses. Deriving and gaining Board approval for the budget is only one step in the process. The next step is to track actual results against the budget, on a month-by-month or at least quarter-by-quarter basis, showing all variations from expected, both positive and negative, and giving a full report to the Board that includes explanations of large variances. H. Avoiding the Appearance of Insider Transactions Chapter 5, section H discusses the issue of "private inurement," which is defined as transferring (directly or in any one of many indirect ways) a non-profit's funds to a private individual or shareholder other than for full and fair value of goods or services provided. The consequence of the IRS or someone else finding evidence of private inurement can be loss of exempt status, but at the very least it will mean considerable turmoil and acrimony in your organization. Although it is legitimate for officers and other insiders to receive funds from the organization, all paperwork details and rules surrounding those disbursements should be scrupulously observed, because of the possible appearance of diverting funds to insiders (private inurement). I. Financial Practices to Avoid Loans of any duration to officers should be avoided if at all possible. If unavoidable, the shorter their duration, the better. See the discussion on travel advances under Petty Cash, in section F, above. If loans are unavoidable (and it is hard to imagine circumstances under which they are truly unavoidable, then a fair market rate of interest must be paid to the organization to prevent a clear case of private inurement. It is well worth noting that any loans to or from officers or other insiders that remain outstanding at year-end must be disclosed in full detail on the Form 990-EZ or 990 filing, or on the group 990 filing, if the chapter in question participates in that filing. All such 990s are available for public inspection, and the information about officer loans cannot be suppressed. See Chapter 5, section L, for more details on the subject of public inspection of 990s. Chapter expenditures other than one's own reimbursable business expenses should be made by direct disbursement from the chapter to the original vendor, rather than charged to personal accounts and reimbursed. It is tempting to "convenience" the chapter by charging office equipment and supply purchases on one's personal credit card until a reimbursement check can be issued, and it is not illegal or a gross violation of any tax rules to do so, but it is best avoided. 4 Chapter 4 The reason is the heavy burden of documentation in order to avoid appearance of private inurement, and even if documented, there is the commonplace suspicion that you charged it to your own credit card for the primary reason of receiving frequent flyer miles. Dealing in cash is best avoided altogether, for obvious reasons. Financial transactions between the chapter and vendors owned by officers or other insiders, or by members of their families should be avoided. This is so even if the chapter is really getting a discount or some other form of "good deal." Such transactions are not prohibited if they are for fair value, but the appearance problem and additional recordkeeping burden are generally too much for any cost savings to overcome. Investing chapter funds in speculative or high-risk investment vehicles is generally to be avoided, and investing in financial institutions or instruments that might be seen to benefit officers or other insiders should be avoided under all circumstances. It is not necessary to invest in the lowest, most conservative government-backed vehicles available, although that is a very safe idea. Some investment in nationally recognized diversified mutual funds that invest in publicly traded stocks or bonds has become normal for non-profits, given the recent bull market in equities. The rule of thumb is to keep portfolios diversified to minimize risk, and to tilt more to the conservative side than one would do with one's own individual funds. 5