the life and letters of raja rammohun roy

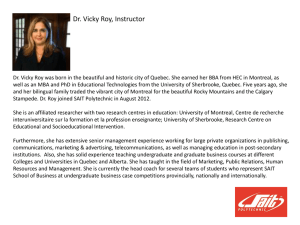

advertisement