Ramsey - Harvard University Department of Physics

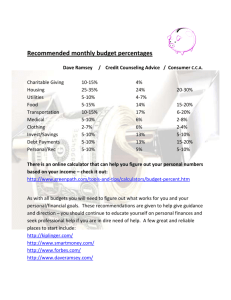

advertisement

Short Biography of Norman Foster Ramsey Norman Foster Ramsey, who died on November 4th 2011 of natural causes, was the last of a towering group of physicists, van Vleck. Schwinger, Purcell, Pound and Ramsey, with different personalities who worked in harmony, although rarely in unison and changed the shape of Harvard University physics department just after the Second World War. He was born on August 27, 1915 in Washington, D.C. His father, a Brigadier General in the Army Ordnance Corps had fought in 3 major wars: SpanishAmerican, and World Wars I and II. During his father’s assignment in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Norman acquired a Kansas accent and graduated from high school with a high academic record at the age of 15. When his parents moved to New York City he entered Columbia College in 1931, earning a BA in Mathematics in 1935. On a Kellett Fellowship to Cambridge University, he earned a 2nd BA in Physics (later a D.Sc.). He returned to Columbia University in 1937 and joined the research group of I.I. Rabi who had invented molecular beam magnetic resonance a couple of months earlier. Ramsey played a crucial role in proving that that the deuteron is not spherical but has a quadrupole moment. However, to satisfy the demands of sole authorship, he only received the PhD for a paper on rotation \al moments in H2 and D2 in 1939. This was an entry into the most fundamental particle physics of the time – nucleon-nucleon interactions - which he studied further at the Carnegie Institution. In 1940 Ramsey began war work. At the MIT Radiation Laboratory he headed the group developing radar at 3 cm wavelength. In 1943 he went to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to work on the Manhattan Project. Perhaps his most important assignment was his appointment in 1945 as head of the Atomic Energy Laboratory in Tinian in the northern Mariana Islands. His group took pieces of metal that came in by the cruiser Indianapolis, assembled them into “devices” or “gadgets” (the atomic bombs), and loaded them on airplanes for delivery to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The terrible weapon he put on board Enola Gay finished a terrible 6-year war for which we must be grateful. The history is usually told in military archives but the crucial role of the scientists is often relegated to private conversation. After the brief return to Columbia University Ramsey was persuaded to join the Harvard faculty in 1948. One of his many roles was to complete the Harvard Cyclotron which had been planned and designed by Kenneth Bainbridge and Robert Wilson. He also established a molecular beam laboratory where he invented the separated oscillatory field method (now called the Ramsey Method) to enable accurate measurements to be made. This was the invention for which Norman won the Nobel prize. He and his graduate students measured in many different molecules a number of molecular and nuclear properties concentrating on the diatomic molecules of the hydrogen isotopes since these molecules were most suitable for comparing theory and experiment. The subject of molecular beams was also where his greatest teaching lay. In the 1950s he started a course on molecular beams which led to a classic monograph which became the bible for many generations of atomic physicists, One of his students, Dudley Hershbach has stated that it was his introduction to the field in which he himself won the Nobel Prize in chemistry. It was also in the 1950s that Professor Wendell Furry had problems with the House unAmerican Activities Committee. While it was Robert Pound who collected money from a unanimous physics department for Furry’s legal defense it was Ramsey who testified in Washington in defense of his colleague. Ramsey began a sabbatical leave in 1954 at a nuclear physics conference in Glasgow. Already an acknowledged leader in the field he was asked to give an after dinner talk. He proposed a toast to the atomic nucleus whose collective aspects and independent particle aspects live in harmony - unlike the collective emphasis of the USSR and the individual emphasis of the USA. Norman always talked a lot and very loudly. He would have been an excellent Presidential candidate before the days of radio and TV. On a bus from Oxford to London later that year he was taking loudly in the back when the bus driver stopped, walked back and asked him to talk less loudly because he was disturbing his driving! Norman was always positive. He bubbled over with ideas and enthusiasm. He could not have carried out all his ideas himself. But he was excellent at delegation. He basically delegated to one of us (Richard Wilson who joined the Harvard faculty in 1955) the upgrade of the cyclotron and later Harvard’s share of plans for the Cambridge electron accelerator but joined and coauthored the central experiments (proton-proton scattering and electron-proton scattering) on both. But he was always available for discussion and all the plans, including those for medical work were discussed with him. He spoke at the cyclotron 50th anniversary of the cyclotron in 1979, and a couple of years later at the start of the new (follow-up) cyclotron at Massachusetts General Hospital.His success in administrative tasks and a team leader, shown so well in Tinian, was well known in the corridors of power in Washington. In 1946 he and Rabi took the lead in establishing Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island and while on\n the faculty at Columbia was the first head of the Brookhaven Physics Department, Many administrative tasks outside Harvard followed. Chairman of the General Advisory Committee of the AEC. (1968-1969) Science Ambassador to NATO (1958-1959) where he set up their program. In 1965 the physics community with widespread acclaim asked him to be President of the Universities Research Association which task he undertook for 15 years. At URA he resolved conflicts between east coast scientists who following the Brookhaven National Laboratory tradition felt that the facilities should be open to all, and the west coast scientists who followed the Berkeley tradition of giving priority to members of the laboratory and official visitors. He selected the director for Fermilab and chose Bob Wilson. He helped Bob build an accelerator for 2/3 the cost Berkeley had estimated and with 60% higher energy. His personal schedule during this period is incredible but true. Although he took half time leave from Harvard, he worked a full schedule on both. Typically he would fly from home to Washington, DC, for a morning meeting with URA staff, exploit the time difference to get to Chicago for an afternoon meeting with Bob Wilson and his senior staff, return to Cambridge in the evening, and be up early next morning to teach. Although URA was for particle physics his basic research activities were by now solely on developments in atomic physics. He never participated in an experiment at Fermilab. His development of the Atomic Hydrogen Maser in 1960 with his former graduate student Dan Kleppner allowed vastly improved precision in atomic clocks. Also in 1950, Ramsey together with our Harvard colleague Professor Ed Purcell realized that there was no fundamental reason why the neutron could not have an electric dipole moment, and with their student (Dr J.H. Smith) in Brookhaven made the first of many such searches which have intensified in recent years. Other students (Lamoreux and Heckel) started a program in Grenoble using ultra cold neutrons which carried the sensitivity down by a factor of ten thousand. Unlike most of us he knew when to stop. On his 65th birthday he handed over responsibility of URA to others, declined formal administrative roles and closed his lab at Harvard. But his interest and advisory role continued. He remained a collaborator at Grenoble on the electron dipole moment experiment and wrote review articles on the subject. He was continually asked to travel, give lectures and teach, and the honors still poured in. Perhaps more importantly on a personal level, his trips were now longer and he took more than a day at his destinations. Ramsey married Elinor Jameson in 1940, and had 4 daughters. After Elinor died in 1983 he married a Ellie Welch of Brookline, Massachusetts a widow whom he met at the Appalachian Mountain Club and who shared his enthusiasm for hiking . Their trips ranged from trekking in the Himalayas to walking across northern England. Between them they have 7 children and 6 grandchildren who survive him. Norman was also very helpful on a personal basis to students and colleagues. The family of one of one us (Richard Wilson) were recipients of such help on more than one occasion. Norman was fun, and inspiring to be with. We will all miss him. But as various seminars and obituaries come along it is clear that his ideas and his work lives on. In addition to the other degrees Ramsey received an honorary D.Sc. from Case-Western Reserve University, Middlebury College, Oxford University, The Rockefeller University, The University of Chicago and The University of Sussex. His many honors included in addition to the Nobel prize in 1989, the: E.O. Lawrence Award, 1960; Trustee Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1962 - 86; Davisson-Germer Prize, 1974; Trustee of The Rockefeller University, 1977 ; President of the American Physical Society, 1978 - 79; Chairman Board of Governors of American Institute of Physics, 1980 - 86; President of United Chapters of Phi Beta Kappa, 1984 - 88 the IEEE Medal of Honor, 1984; Rabi Prize, 1985; Rumford Premium, 1985; Chairman Board of Physics and Astronomy of National Research Council, 1985 - 1989; Compton Medal, 1986; Oersted Medal, 1988; National Medal of Science, 1988. Vannevar Bush Medal 1995 .