Content - Consumer Unity & Trust Society

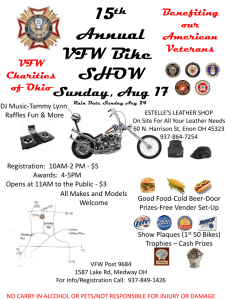

advertisement