Statutory Bases for Philippine Rehabilitation

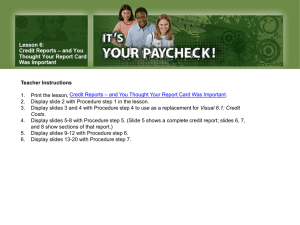

advertisement