A Concept Paper Toward a Bottom-up Measurement and Evaluation

advertisement

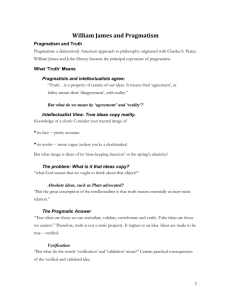

A Concept Paper Toward a Bottom-up Measurement and Evaluation Protocol for Energy Efficiency Programs David Sumi, Ph.D., and Bryan Ward, PA Consulting Group Introduction There is increasing interest internationally in quantifying and verifying energy savings attributable to energy efficiency programs so that these impacts may be credibly applied toward various initiatives. These initiatives include a host of international, multinational, and national voluntary or mandatory efforts to register, certify, or regulate energy use and/or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The purpose of this paper is to concisely outline some criteria, concepts, and terms toward a program evaluation protocol that will be developed by the Efficiency Valuation Organization (formerly the International Performance Measurement & Verification Protocol – MVP; see www.ipmvp.org and Volume I, Concepts and Options for Determining Savings). As with the MVP, the goal is to provide a framework of current best practice techniques for verifying results of energy efficiency projects – and specifically for energy efficiency programs. The principal summarizing idea of this paper is that a program evaluation protocol will be an essential part of an overall scheme for the measurement and verification of energy efficiency improvements in Europe. Such a protocol would be very useful in supporting the planned Directive on energy end-use efficiency. Many of the concepts and terms introduced in this paper are currently in place in an ongoing evaluation in the U.S. for the state of Wisconsin conducted by a U.S. subsidiary of the U.K.-based PA Consulting Group. Further information and reports for this evaluation, and in particular the energy impacts reporting “system,” can be obtained at the following web site: www.doa.state.wi.us (click on “Reference Center” then “Focus on Energy Evaluation Reports”). The concepts and terminology used in this paper are also generally consistent with those used in the state of California, as reflected in the development of The California Evaluation Framework (Prepared for the California Public Utilities Commission and the Project Advisory Group, February 2004, by TecMarket Works and a project team). This paper draws on the Wisconsin case study because of PA’s familiarity with the evaluation scheme, and because it is a case study example of: regularly reported energy savings (and environmental benefits) across a complete portfolio of government-sponsored programs serving all customer sectors with different evaluation approaches tailored to various program designs, measures, etc. where the various approaches all “roll-up” with energy impacts consistently expressed as verified gross and verified net, and the verification research underlying the energy savings reporting is based (at least to some important extent for each program) on ex post statistical adjustments (e.g., measurements with statistically representative samples) 1 24/02/2005 A Scheme for Measurement & Verification of Energy Efficiency Improvements In order for a bottom-up measurement and evaluation protocol to effectively support the proposed Directive, we argue that it must be certifiable, implementable, comprehensive, and able to evolve over time (by implementable we refer to the ease with which the protocol can be adopted and established). These criteria are shown in Figure 1, along with their supporting attributes and methodological practices. The remainder of this paper will focus on the criteria and briefly describe these attributes, concepts, and methods (with key terms and concepts italicized). Some examples are also provided which illustrate use of the concepts and methods. In order for a bottom-up measurement and evaluation protocol for energy efficiency programs to effectively support the Energy Service Directive it must be certifiable, implementable, comprehensive and able to evolve. Certifiable Sound Methods Replicable Documented Independent Implementable Allows for incremental gains in accuracy Cost Effective Understandable Comprehensive Able to Evolve Across Geographies & Climates Covers All Program Types New programs New Technologies Current Best Practice Techiques Budget Levels New Certification Requirements New Techiques Common Terms * Program tracking database * Sampling methodology * Maximum acceptable sampling error * Verification of installation (verified gross) * Verification of attribution (verified net) * Focus on greatest areas of uncertainty * Focus on greatest sources of savings * Techniques tied to program design Deemed vs. Individually calculated Stipulated vs. Directly measured Definition of baseline Participant survey vs other analytical options Metering Billing analysis Building simulation Figure 1: Criteria and Attributes of a Bottom-up Measurement & Evaluation Protocol 2 24/02/2005 Certifiable A crucial criterion for a measurement and evaluation protocol is that its application should provide increased confidence in the determination of actual energy savings. That is, there should be a basis for the energy efficiency program sponsor, the Member State government, and the Commission to accept that the energy savings are valid and accurate. We think the following attributes contribute to certifiability: Sound, reliable methods. Methodologies are well established for measuring energy use quantities both pre- and post-retrofit. Of particular importance for a protocol is to: (1) assist in determining on a measure- or technology-specific basis the methods that can be expected to meet at least minimum requirements for statistical validity; and, (2) apply those methods to the energy savings parameters with the greatest expected uncertainty. In many cases these measurement methods will correspond to the options provided in the IPMVP, but the application of the measurement option will be incorporated in a sampling methodology that enables valid measurements for a sample to be extrapolated to a “population” of program projects or measures. Replicable. This refers to the ability of protocol methods and procedures to be applied for the same projects/measures by other independent third party evaluators with essentially the same results (allowing for adjustments to account for different conditions commonly affecting energy use). Documented. The means by which a protocol is applied must be well documented and thereby transparent, i.e., another third party evaluator should be able to understand why, how, and with what results a protocol was applied. Independent. Independent third party evaluation is a key “best practice” underlying use of an evaluation protocol. Common terms. A fundamental contribution of a measurement & verification protocol is to provide a common set of terms. The following provides an example of terms and associated verification steps currently used in the ongoing evaluation in the U.S. for the state of Wisconsin (cited above). Verification of tracked energy savings. The program sponsor (government agency, non-government organization, or private sector entity) must maintain a program tracking database that includes all of the energy efficiency measures and actions taken within the program. The term “tracked” is used to signify that these savings result from program efforts directly counted (or tracked) by program sponsors. This is the fundamental foundation for a program-based M&V protocol. The table below provides definitions for each of the various tracked savings impacts incorporated in the Wisconsin impact evaluation system. Currently, the verified gross energy savings is being used for publicly reported impacts, while the verified net energy savings are used for the economic and benefit-cost analyses. 3 24/02/2005 Table 1. TRACKED ENERGY IMPACTS Gross Reported Savings Verified Gross Savings Verified Net Savings Energy savings as reported by the program sponsor, unverified by an independent evaluation. Energy savings verified by an independent evaluation based on reviews of the number and types of implemented improvements, and the engineering calculations used to estimate the energy saved. Energy savings that can confidently be attributed to program efforts. Evaluators make adjustments for participants who were not influenced by the program (i.e., additionality). Using the entries in the program tracking database as a sample frame, a sampling methodology is used that determines the sample for which the verification steps are applied. Thresholds for maximum sampling error are agreed between the program sponsor, the evaluator, and the state government. Any entry in the program tracking database must have a non-zero probability of being sampled for the verification measurement. For purposes of clarity, tracked energy savings can be distinguished from nontracked energy savings in that they are not directly counted (tracked) by program sponsors. Nontracked energy savings are likely to consist of a combination of savings resulting from participant spillover (e.g., participants who, after an initial program experience, go on to adopt more energy saving products or practices without program assistance), market effects (e.g., changes in “marketplace” practices, services, and promotional efforts which induce businesses and consumers to buy energy saving products and services without direct program assistance), and unclaimed rewards (e.g., people who intend to submit the paperwork in order to claim rewards but fail to do so). All of these nontracked energy impacts are potentially attributable to a program, but, we would argue, are not amenable to the bottom-up approach that is the focus of this paper. However, we also note that nontracked savings are an extremely important source of energy savings. They can be, for example, a direct extension of steps toward verification of net energy savings via the gathering of data that document the effects of a program on a specific market. An example from the Wisconsin case study is the use of CFL sales tracking data to estimate changes in product market share that can be confidently attributed to the presence of a program explicitly seeking to influence the CFL market in a specific geography. 4 24/02/2005 Figures 2 and 3, appended to this paper, illustrate schematically how some of these terms and measurement methods are combined in M&V for a non-residential custom measures program (Figure 2) and the tracked savings from a residential compact fluorescent lighting (CFL) program. Both examples are taken from the ongoing evaluation in the U.S. for the state of Wisconsin. Implementable A measurement & verification protocol must be relatively easy and straightforward to adopt and establish. If this criterion is not met there will be little likelihood that the primary criterion – certifiability – will be achieved. Key attributes for ease of implementation include: Allows for incremental gains in accuracy. Balancing uncertainty in measurement validity and cost is an ongoing resource issue for evaluation. One practical approach to this issue is to implement the M&V over time in a manner that allows for certain know sources of uncertainty to be addressed in a staged manner. That is, if there are two primary sources of uncertainty for measurement of energy savings, one source may be addressed the first year and the other in a second year of the program. In the example of a residential CFL program, the parameter with the greatest effect on savings may be the actual installation (and retention) rate of CFLs obtained through the program. This could be determined during the first program year by a telephone survey with a statistically representative sample of CFL recipients. The somewhat more expensive measurement task of on-site metering a sample of CFL installations for hours of use could be conducted in the second year. [It should be noted, however, that if measurement results obtained in the second year are significantly different than the assumption used in the first year for hours of use, an ex post adjustment to energy savings for the first year may be required.] Cost effective. The cost of measuring certifiable energy savings will depend on many factors (the IPMVP has a good discussion of cost factors; see www.ipmvp.org and Volume I, Concepts and Options for Determining Savings, section 4.10). Among the most useful procedures to balance cost and uncertainty in M&V are to: (1) understand the measurement methods and techniques that are best suited to the program design; (2) focus on the energy savings parameters with the greatest uncertainty; and (3) focus on the greatest sources of savings (among programs within a portfolio of programs, or among projects or measures within a program). Understandable. There are perhaps two levels of comprehension that are most relevant. A protocol should embody, to the extent possible, non-complex and relatively simple terms and methods. The basic terms and energy savings measurement methods should be comprehensible to stakeholders who are not professional evaluators. However, those actually conducting the methods and techniques, and who are responsible for independent third party verification/certification, are likely to require professional training. 5 24/02/2005 Comprehensive In order to be implementable for all Member States (and internationally) a measurement & verification protocol must provide a broad menu of techniques adaptable to determining program savings in varying conditions. This criterion suggests the following attributes: Applicable across geographies and climates. Different end-uses and technologies will offer the greatest energy savings potential in different geographies and climates. A protocol must be adaptable and able to present procedures, with varying levels of accuracy and cost, which can be used to certify savings. Covers all program types. The portfolio of energy efficiency initiatives and programs will differ across each of the Member States. A protocol, and its concepts, terms, and methods must be applicable in some manner to all program designs that are amenable to the bottom-up measurement approach (i.e., are predicated on a program tracking database including all energy savings that the program sponsor intends to claim). Current best practice techniques. Like the IPMVP, a program-level evaluation protocol should provide an overview of current best practice techniques available for verifying results of energy efficiency programs amenable to the bottom-up measurement approach. Many measurement options are available, including participant surveys (self-reported data for energy savings parameters), review of project engineering documentation, metering, billing analysis, and building simulation (often suited to new construction programs). Thus, all of the measurement options of the IPMVP, plus other primary and secondary data collection methods, should be available to a program-level protocol. In contrast to the IPMVP, accurate, valid, and reliable measurements are conducted with a statistically representative sample of the overall program participant population (and extrapolated to the population). Budget levels. As suggested in discussion of the need for a protocol to be cost effective (above), a comprehensive protocol can be suited to energy efficiency programs with widely varying implementation budgets. Again drawing from the ongoing energy savings evaluation in the U.S. for the state of Wisconsin, we have found that an important distinction involves two broad choices of M&V techniques – each incorporating the ability to apply ex post adjustments to energy savings using statistical criteria. The first is based on energy efficiency measures that have stipulated or “deemed” savings values (e.g., a kWh savings value that would be assumed for all installations of the measure in a particular geographic area). This approach we have found suitable for mass residential EE programs, or small C&I programs with routine measures (e.g., lighting measures). The second protocol approach addresses more “custom” measures, i.e., measures whose energy savings potential would typically be assessed with site-specific audits. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate schematically the different approaches. 6 24/02/2005 Able to Evolve A program evaluation protocol must be a “living document” that provides for methods and procedures – and program designs – that evolve over time. Certainly the Member States can expect to develop over time new programs, incorporating new technologies. Thus, new measurement procedures will be desired. And, the certification requirements of “external programs” (EU Emissions Allowance Trading Schemes, White and Green Certificates, etc.) can all be expected to change over time. Often of particular importance is the measurement of baselines for use in specific determinations of energy savings. A protocol must adequately address the need for periodic re-specification of baseline data. This can be particularly pertinent to measurement approaches relying primarily on deemed savings and employing parameters with “stipulated” values that require testing over time. Future Work Like the project-specific IMPVP, continued international development of a programspecific evaluation protocol will involve increasingly broad international participation. Going forward, the IPMVP web site will use its site archives to document the development of an international program evaluation protocol. Of near-term interest, the summarizing idea of this paper is that a program evaluation protocol will be an essential part of an overall scheme for the measurement and verification of energy efficiency improvements in Europe. Such a protocol would be integral in supporting the planned Directive on energy end-use efficiency. 7 24/02/2005 Example Program tracking database Engineering Review Sample Documentation Request Documentation Reviews Sample Engineering Verification Installation Attribution Large, Complex Completed Projects Small, Simple CATI Sample CATI Sample Installation Attribution Population Adjustment Factors Source: “Focus on Energy Business Programs and Evaluation Meeting: How Do We Do It?” presentation by Miriam Goldberg, KEMA-XENERGY Inc., and Jeff Erickson, PA Consulting Group. Madison, Wisconsin: September 30, 2003. Figure 2: Business Programs M&V Process CFL Example Program tracking database Rebated CFLs Small, Simple CATI Sample CATI Sample Installation? Hours of use? Replaced bulb wattage? Population Adjustment Factors Figure 3: Residential Programs M&V Process 8 24/02/2005