Chapter 2 - University of Wisconsin

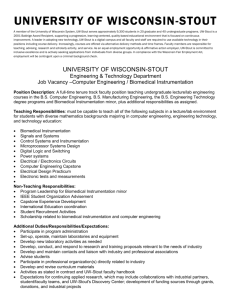

advertisement

The Economic Impact of the University of Wisconsin-Stout on Local Economy Working Paper No. 2007-01 May 2007 Dr. Rula Qalyoubi-Kemp Social Science Department University of Wisconsin – Stout kempru@uwstout.edu Acknowledgments Without the assistance of several campus offices and personnel this study would have never been completed. Meridith Wentz from the University Budget, Planning and Analysis provided a major help in coordinating efforts in data collection. Many thanks to Char Coss and Jo Johnson from Human Resources, Scott Griesbach from the University Housing, Amy Lane from Career Services, Michael Potter from the accounting, and Patti Cramer from the Budget, Planning and Analysis. I am grateful to Dean John Murphy for his financial support. Special thanks to Jenna Wendorf, my research assistant and Becky Simonson from the Social Science department for her input. I am indebted to Richard Tyson for his support and assistance. The findings, interpretations, conclusions and any errors are the author’s own responsibility and should not be attributed to any personnel and/or offices mentioned. About the Author Rula Qalyoubi-Kemp is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin – Stout since 2006. She earned her Ph.D. in Economics from Colorado State University in 2005 with two fields; Public Finance and Taxation and, Environmental and Resource Economics. Additionally, her area of expertise includes Economic Development and Regional Economics. In 2005 professor Kemp wrote the executive summary to his Majesty King Abdullah II of Jordan about Jordan’s long run sustainable economic growth – potentials and impediments. She has four years of experience working in economic consulting firms, nationally and internationally. Currently, professor Kemp is working on assessing restrictions on upward labor mobility in Jordan and researching the institutions that encourage entrepreneurship in China. Professor Kemp reactivated the Social Science Research Center hoping to help Dunn County achieve its economic potentials. This is done by identifying the dynamics of the regional economy and by investigating the forces that shape potential local growth and capturing growth spurs from neighboring states. This is especially true since Dunn Country is in partnership with the I-94 Corridor Technology Zone Program. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………… 4 I. Introduction …………………………………………………………… 7 1. University of Wisconsin – Stout ……………………………… 7 2. The Impact of the University as a Higher Education Institution .. 9 II. Methodology ……………………………………………………….... 11 1. Scope and Objectives ……………………………………….. 11 2. The Multiplier Effect ……………………………………….. 12 3. Leakages and the Regional Purchase Coefficient ………….. 13 4. The IMPLAN System ……………………………………….. 13 5. Margins and the Deflator …………………………………… 14 6. Data ………………………………………………………… 15 III. Impact of UW-Stout on Local Economy …………………………….. 15 1. University Operation and Equipment Expenditures …………. 15 2. Payroll ……………………………………………………….. 18 3. Students Expenditures ……………………………………….. 21 4. Visitors Expenditures ……………………………………….. 23 5. Impact Summary Tables …………………………………….. 27 6. UW-Stout Direct Spending and Impact …………………...… 28 IV. Concluding Remarks ………………………………………………… 30 References ………………………………………………………………………… 32 3 Executive Summary The primary focus of this study is to estimate the University of WisconsinStout economic impact on local economy. Total spending by UW-Stout institution, its staff, students and visitors have “ripple effects” on local and surrounding economies, and that depends on the estimate amount of local spending. When these expenditures are factored in, they measure the amount of dollars that circulate through the region. Therefore, spending by the university as an institution, its employees, students and visitors generates a multiple effects on the local economy beyond its initial spending. This ripple effect can be seen in terms of increase in output, employment and increase in income levels in Dunn County. Key findings of this study for the 2005-06 academic year includes: The $49.6 million in total spending on auxiliaries and other activities produced a total impact of $67.44 million in terms of local output. For every dollar in initial university-related spending, there is an additional 36 cents of output increase. The university added a total of $44.4 million of additional total labor income in Dunn County. Labor income includes salaries and wages which directly impacts household spending and the presence of the university in Dunn County generated an additional 1,357 full time jobs. 4 Spending by university employees produced a total effect of $42.1 million in terms of local output. Total job creation by employees spending is 545 additional jobs and the estimated total labor income earned is $12.7 million. The estimated impact of the university students spending is $79.7 million in terms of local output; for every dollar in initial student spending, there is 59 cents increase in output. Student expenditures supported 1,578 full time jobs, earning $55.5 million in Dunn County. The estimated visitors spending generated $23.2 million in terms of local output, for every dollar visitors spent there is an additional 47 cents of output increase. Visitors supported 455 full time jobs with earned income close to $7.3 million. Major employment categories are medical services, food and drinking services, residential care services, sanitation, personal care services, motor vehicles and parts dealers, hotel and motels, recreational sports centers, finance, insurance and real estate services, construction, stationary and related product manufacturing. Major industries affected by university total spending is telecommunications, transportation, architecture and engineering services, travel agencies, power generation plants, retail and whole sale trade, furniture, electronics, gas stations, agriculture sector, sporting and athletic vendors, commercial laundry and dry cleaning services, food and beverage industry, lumber and wood, and confectionery manufacturing. 5 The total estimated sales tax revenue increase is $11.5 million for Dunn County and the total estimated income tax revenue increase for the state of Wisconsin is $7.2 million. Total contribution of the University of Wisconsin-Stout amounts to more than $367 million to the local economy and more than $386 million for the state of Wisconsin. 6 I. Introduction 1. University of Wisconsin-Stout The school, founded in 1891 by James Huff Stout provided Manual Training for the Menomonie Public Schools. In 1899, a Kindergarten Training School began to prepare kindergarten teachers and a School of Physical Culture, which provided physical training opened in 1901. In 1903, training schools for manual training teachers and domestic science teachers were added. From 1908-55, it became the Stout Institute, and was designed to "provide facilities in the way of buildings, equipment, and teachers, through which young people of both sexes may secure such instruction and training in industrial and related lines of educational effort as will enable them to become efficient industrial, social, and economic units within their environment." In 1911, following Senator Stout's death, ownership transferred to the State of Wisconsin. From 1955-64 the institution came under the jurisdiction of the Board of Regents of the State Colleges, a move that the institute board resisted, fearing a loss of prestige from being a special college. The institution changed name from 1964-71 to Stout State University in an attempt to provide a plateau to reach out wider public enrollment. The name change was authorized by the Board of Regents who believed that the "state colleges had reached another plateau in their development." Increased enrollment brought new and enlarged facilities. A traditional focus was maintained even while new majors were added and new directions were given to established majors. In 1971 the Wisconsin State Universities and the University of Wisconsin campuses merged to form the University of Wisconsin System. Stout was designated by the Board of Regents as one of only two special mission universities in the UW System. Stout was to offer focused programs "related to professional careers in industry, technology, home economics, applied art and the helping professions." During the academic year 2005-06 the university enrolled more than 8,400 students and awarded more than 1,350 degrees. The university employed more than 3,880 faculty, staff and graduate assistants with student/faculty ratio is 19:1. The 7 university has 24 undergraduate majors, 30 undergraduate minors, 12 specialization, 16 graduate majors, 1 graduate minor, and 2 advanced graduate majors. In 2007, UW-Stout was designated as Polytechnic University. The goal of a Polytechnic University is to combine teaching and applied learning with the changes in the business community. University of Wisconsin-Stout became a “comprehensive, career-focused polytechnic university where students, faculty and staff use applied learning, scientific theory and research to solve real-world problems, grow the state economy and serve society.” This bold move is intended to integrate the university with the business and industrial communities and is projected to complement the Stout Technology Park. The Stout Technology Park was established in 1990 to “develop close relationships with businesses and industries to provide real-world educational opportunities.” This partnership is a first step to pave the way for the development of the I-94 Corridor Technology Zone program. UW-Stout offers specializations in Manufacturing Engineering, Packaging, Graphic Arts and Design, Hotel and Restaurant Management, Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, CAD/CAM Programs, and Computer Manufacturing Simulation. These specializations may prove to be a source of workforce that could support industries in the I-94 Corridor Technology Zone program. This consortium has multiple advantages; from a teaching standpoint, it allows instructors to use not only new technology, but new ideas and methods of teaching. It also provide students new opportunities to see the business community they will be entering and develop an understanding of their future careers that cannot possibly be found in a typical classroom. The business community benefits from this type of learning since they are assured to be hiring well-informed, educated individuals that have been taught with the most up-to-date information and technology that is already currently being used or will be used in their fields. Incorporating the business community with UW-Stout will not only ensure the success of the students and the university, but also the community as well. 8 The University of Wisconsin – Stout is located in Menomonie, Wisconsin in Dunn County and is a unique location for college students to get an education. Normally a “sleepy,” quiet town, Menomonie wakes up when over 8,000 college students get to town in the fall. The area has amentias like Lake Menomonie, the Red Cedar Trail, and Mabel Tainter Theater that not only provides students with activities, but also educates them through culture and history that can only be found in this part of Wisconsin. 2. The Impact of the University of Wisconsin - Stout as a Higher Education Institution For the local (and U.S.) companies to compete locally (and globally) the labor force have to be equip to handle the changing nature of the business environment. The university not only injects spending directly and indirectly to the local economy but also engages in human capital formation and development. The economic significance of UW-Stout as a higher education institution has both tangible and intangible effects. The tangible effects can be conceptualized in the university’s direct expenditures on goods and services, physical structure, capital improvements, payroll, students and visitors spending. These monetized transactions support a wide variety of local businesses and, increase sales and State income tax revenues. Local businesses benefit from these purchases in terms of increase in proprietors’ income and business expansions and, these businesses in turn demand more labor and capital goods which could support other businesses and industries. Human capital is made up of individual people’s capacity for labor, particularly the energy, knowledge and skills that each can personally bring to his or her work. Investing in human capital has a rate of return that can be measured in terms of wages earned and increase in quality of life. Although quality of life is a little harder to quantify beyond material acquisition and health, but the increase in potential earnings with higher education can be conceptualized in Figure 1. 9 Figure 1: Potential Earnings with Bachelor’s Degree The Figure above illustrates a direct relationship between national median earnings and their corresponding percentage of adult population with bachelor’s degrees. Hence, higher education institutions provide individuals with the means to increase their future potential income. Additionally, higher education institutions carry out research which forms bases of commercial achievements. Also, universities provide education that shape and sharpen the intellect, character and skills of our future labor force. The intangible significance of the University of Wisconsin-Stout is even more important with the “hands-on” knowledge base learning. Building the human capital necessary to fuel innovation, creativity and originality will be the driving force for businesses and industries for the economies of the 21st century. Shaping our labor force with the know-how fosters the development of our intangible capital and increases productivity and hence wages. Therefore, the non-tangible effects of UW-Stout, as a higher education institution, have both direct and indirect consequences of shaping the future of the local (and U.S.) companies’ competitiveness. Moreover, because universities engage in purchases, employees, students and visitors demand goods and services, and pay sales and income taxes, state and local government benefit in terms of revenue increase which could potentially increase local and state government appropriations on socially constructive programs. Hence, 10 the cycle of purchases and spending triggered by the university, its employees, students and visitors have both direct and indirect results on the local economy. This is true especially of rural universities. II. Methodology 1. Scope and Objectives This study examines the impact of four actors namely, the university expenditures, university payroll, spending by university students and visitors. The impact attributable to the university is measured in three different areas: 1) number of jobs that the university supports directly or indirectly 2) additional labor income. and 3) additional output (sales) that the university generates. Figure 2 illustrates the abstract structure under examination. For the purposes of this study the local economy is defined to include Dunn County. Figure 2: Abstract Structure University Expenditures Employment Impact Payroll UW-Stout Local Economy Students Income Impact Output Impact Visitors 11 Additionally there will a discussion on local sales tax and income tax revenue increase resulting from the purchases by the university, employees, students and visitors. 2. The Multiplier Effect The total impact of UW-Stout on the local economy, also recognized as the multiplier effect, is equal to the sum of three elements: the direct effect, the indirect effect and the induced effect. The direct effects are the initial consequence caused by university spending, university payroll and spending by students and visitors. Due to the exchanges between firms, industries, and social institutions (household, Federal government, State and local government, enterprises, capital and inventory) that naturally arise within the local economy, the direct effect commences a series of iterative rounds of income creation, spending and re-spending that can be observed in the indirect and induced effects. The indirect effects are changes in production, employment and income that are caused by the inter-industry purchases and spending prompted by the direct effect. This can be seen as production changes in backwardlinked industries caused by the changing input needs of directly affected industries. The induced effects arise due to changes in household income and spending patterns caused by direct and indirect effects. Since the total impact of the university expenditures is a compound of the initial expenditures, the total effect is expressed as a multiplier effect. The total effect is the sum of the direct, indirect and induced effects. Therefore, the total impact of the university on the local economy is larger than the initial spending. For example, an output multiplier of 1.3 indicates that for every million dollars spent (direct expenditure) an additional 0.3 million dollars is generated within the local economy. Similarly, an employment multiplier of 1.6 indicates that for each job created by direct expenditure, an additional 0.6 full time jobs created or supported. Further, labor income multiplier of 1.8 implies that for every million dollars spent an additional .8 million of labor income created within the local economy. 12 3. Leakages and Regional Purchase Coefficient Industries produce goods and services for final demand and purchase goods and services from other producers. These other producers, in turn, purchase goods and services. This buying of goods and services (indirect purchases) continues until leakages from the region (imports) stop the cycle. Thus, the multiplier effect tracks down the flows of spending by institutions until original spending leaks out of the region. Leakages are payments made to imports sectors which do not in turn re-spend the dollars within the region and the larger the leakages are the smaller the multiplier effect resulting from economic activities. Therefore spending on goods not produced locally has little impact of local spending by any type of social institution. To implement a sound trade flow the regional purchase coefficient factor needs to be adjusted to reflect such leakages. Therefore, the regional purchase coefficient is the ratio of locally purchased to imported goods. An example a regional purchase coefficient of .95 for dairy products indicates that 95 percent of local demand is met by local producers and 5 percent met by producers outside the study area. 4. IMPLAN System This economic impact study is done using IMPLAN input-output model. It is an integrated software and data package coupled with set of tools for creating regional social accounts and for evaluating economic activities. IMPLAN software allows a user to build a study area, also known as social accounts, customized for a specific region. Social accounts track the monetary flows (both market and nonmarket activities) between industries and institutions. The market flows are those between producers of goods and services and consumers, both industrial, and nonindustrial. The non-market flows are those between households and government, government and households, capital and households and so on. These flows are called inter-institutional transfers. The IMPLAN system is designed to serve three functions: 1) data retrieval, 2) data reduction and model development, and 3) impact analysis. 13 The data accompanied the software is collection of data tabulated by the U.S. Department of Commerce, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and other agencies. Data are tabulated for 509 sectors of U.S. (national, state and county levels) which correspond to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). The IMPLAN database consists of two major parts: 1) a national-level technology matrix and 2) estimates of sectorial activity for final demand, final payments, industry output and employment for each county in the U.S. along with state and national totals. The software allows users to tailor a study region on county level, multiple counties, or state and multiple states. The complete set of social accounts is then converted to the industry by industry formulation of input/output accounts and ultimately the predictive Leontief multipliers. The notion of the multiplier rests upon the difference between the initial effect of a change in final demand and the total effects of that change. The IMPLAN accounts closely follow the accounting conventions used in the “Input-Output Study of the U.S. Economy” by the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the rectangular format recommended by the United Nations. 5. Deflators and Margins To account for inflation, deflators are used to convert impact expenditures from current year to the base year and also can be used to inflate the impact reports of the study area to the current year. This is a necessary step to find expenditures expressed in same year’s dollars as the model’s data. The latest IMPLAN data for the State of Wisconsin are for the year 2004. For that reason, the numbers are adjusted to 2005 dollars, which is the year under analysis. Margins are used to convert purchaser prices to producers’ prices. Margins are different depending on the “final” consumer. Households pay transportation, wholesale, and the full retail margins. Industries or the Federal government pay different margins. For example, government may pay little or no retail margins as it has more buying power. Therefore, margins represent the difference between producer and purchaser prices. Margining assigns direct expenditures to the correct input/output sector multipliers. It splits a purchaser price into the appropriate values. 14 Thus, the value of the impacts, if purchased by end users or consumers, must be divided into the portion going to the retailer, and wholesaler, transportation, and the manufacturer. 6. Data All data used in this economic study are for the 2005-06 fiscal year and are provided by different lists of sources, including the University Budget Office, the Admission Office, the Human Resource office, Career Services, Accounting and the University Housing. To infer a correct impact data, differentiation of expenditures due to university operating expenditures, employees’ expenditures (which is related to payroll), students and visitors expenditures is a necessary step. Therefore, the following section present expenditure information and the impact of each of the categories on the regional economy. III. Economic Impact of UW-Stout on Local Economy 1. The University Operating and Equipment Expenditures According to the Budge, Planning and Analysis 2005-06 Annual Report, UWStout spent almost $118 million; Table 1 displays expenditures by category. Permanent Salaries LTE/Student Help Graduate assistant Total Personnel Table 1 Expenditures Amount $46,208,975 $4,943,551 $500,674 $51,653,200 Percent of Total 41.48 Fringe Benefits $21,589,775 17.34 Service and Supplies $34,069,211 27.36 Capital $2,069,344 1.66 Special Purpose $15,154,605 12.17 Total UW-Stout Expenditures* $124,536,135 100% * There is an additional ($-6,604,992) in Sales Credits, total expenditures are $117,931,143 15 These expenditures consist of wages (non-academic and academic staff) and purchases of goods, fringe benefits, and services from private vendors. Approximately 29.02 percent of UW-Stout non-payroll expenditures, or $36.14 million, occurred in Dunn County. To avoid double counting, total UW-Stout nonpayroll spending in Dunn County is relegate by internal grants and assumed as proceeds to UW-Stout in the form of tuition and fees. Capital spending on construction is added to UW-Stout non-payroll dollars to reflect direct spending that impact Dunn County. Of the $124.5 million only 28.9 percent (34,075,920 million) is UW system appropriation, the rest of the funds are made from academic student fees, government and non-government organizations, and private gifts and grants; Table 2 displays revenue source. State Appropriations Table 2 Sources of Funds Amount Percent of Total $34,075,920 28.89 Academic Student Fees $39,069,622 33.13 Auxiliary Enterprise $22,534,604 19.11 Private Gifts & Grants $2,003,605 1.70 Federal Grants and Contracts $5,902,528 5.01 Federal Student Financial Aid $7,181,370 6.09 Other $7,163,496 6.07 Total UW-Stout Revenue $117,931,145 100% The difference between total revenue and expenditures is due sale credit amounting to $6.6 million. Nearly 29 percent of revenue came from UW System appropriation; students’ fees, tuition, room and board account for 33 percent; federal grants and student aid amount to approximately to 11 percent and almost 2 percent came from private gifts and grants. Excluding fringe benefits, students’ aid and payroll (except for LTE and graduate assistance – they are assumed to live in the area), UW-Stout spend 16 approximately $49,556,015. These expenditures are spent on everything from equipment, construction, food services, and library material. These expenditures pour directly into local economy and the surrounding areas, some spending is indirectly observed yet others have induced impact. Table 3 depicts the impact of UW-Stout expenditures in terms of number of job created, their earned income, contributions to Wisconsin output and the multiplier effects. Table 3 Institution Impact Employment Labor Income Output Total Direct 1,128 39,157,952 49,556,015 Total Indirect 6 166,568 512,259 Total Induced 222 5,096,806 17,471,736 Total 1,357 $44,421,326 $67,540,010 Multiplier 1.20 1.13 1.36 The impact analysis shows that the $49.6 million spent by the university and its auxiliaries produced a total effect of $67.5 million in terms of output. Output is measured by the total value of purchases by intermediate and final consumers – measured in total direct, total indirect and total induced. Output can also be thought as the value of sales, plus or minus inventory levels. Table 3 shows that the university spending produced an additional $18 million of additional spending in the local economy. The multiplier is found by dividing total numbers divided by the total direct. A multiplier of 1.36 implies that for every dollar the university spent on capital improvement there is 35 cents that is generated by the university expenditures. Total job created from UW-Stout presence in Dunn County is an additional 1,356 employees with a value of labor income of $44.4 million. According to the Wisconsin Department of Revenue, the average of Wisconsin Income tax rate is 6 percent thus the additional income tax revenue is $2,665,275.6. Major employment categories are: food and beverage stores, childcare services, office physicians, dentists and hospitals, nursing and residential care facilities, food services, civic, social and professional services. Non-payroll impact on the local economy amounts to $67.5 million with additional $3,667,422.7 in sales tax revenue (according to Wisconsin Department of Revenue, the average weighted Wisconsin sales tax is 5.43 17 percent.) Among the sectors that are effected by UW-Stout presence in the Dunn county area are: real estate, travel agencies, consulting services, architecture and engineering services, financial institutions, legal services, telecommunication, medical services, electronics and appliance, power generation plant, wholesale trade, transportation and gas stations, postal services, furniture, computer system and design, commercial printing, maintenance and repair, meat processing and farmers (dairy, produce, cattle). 2. Payroll According to the University Budget Office, the university employed a total of 1,213 employees at UW-Stout with 598 serve as faculty and academic staff, 37 with limited appointments, 378 are classified staff, 130 are project/limited term appointment and 70 are graduate assistant. Also, according to the University Budget Office, the UW-Stout campus at the end of the 2005-2006 academic year, had a total 1001.9 FTE employees; Table 4 displays FTE employment by category. Table 4 FTE Employment at UW-Stout Unclassified Classified Category FTE Category Non-Instructional 223.95 Project Academic Staff Instr 46.64 Permenent Faculty 289.97 Grad Assis 27.63 Total 588.19 Total FTE 20.14 393.57 413.71 Table 5 depicts gross salaries by category where total wages earned by unclassified and classified, graduate assistants, and limited-term and student employment. 18 Table 5 Gross Wages by Category at UW-Stout Category Gross Wages Unclassified and Classified Employees $46,208,975 Graduate Assistants 4,943,551 Limited Term Employment and Student Help 500,674 Total 51,653,200 Total Wages Excluding LTE and Students $51,152,526 Salary and wages amounted to $51.15 million for employees, excluding LTE and Students. Table 6 displays wages earned by unclassified and classified employees. Table 6 Unclassified and Classified Net Wages at UW-Stout* Gorss Payroll $51,152,526 Taxes Federal Income Payment $5,514,242 State Income Payment 3,150,996 Social Security Payment 3,913,168 Total Taxes 12,578,406 After Tax Income 38,574,120 Leakage Expenditures 7,714,824 Disposable Income $30,859,296 *Excluding benefits and Medicare These figures do not include the amount received as benefits such as health care, retirement, etc. Also, since consumers purchase goods and services using their disposable income, the wage and salary numbers need to be adjusted by subtracting income and social security taxes. Moreover, this study assumes a “conservative” average disposable income ratio of 80 percent.1 Therefore, after adjusting for all taxes, the total disposable income earned by UW-Stout FTE employees was $30.9 million. Using FTE figure instead of headcount is a better approximation to represent the fact that some employees live outside Dunn County. 1 NorthStar Economics, Inc. assumed this ratio to be 90.2 percent. This study assumes that 80 percent of total income earned by UW-Stout is spent locally the rest is spent elsewhere – a more liberal ratio would yield higher impacts. Additionally it is assumed that Income tax withholdings equals tax liabilities on average. 19 The impact analysis shows that the $30.9 million earned by UW-Stout employees produced a total effect of $42.1 million in terms of output. The total effect in terms of labor income created amounted to $12.7 million. The employment multiplier derived by dividing total jobs by the number of direct jobs is 1.35. Expenditures by UW-Stout employees supported a total of 545 jobs in the local area. See Table 7 for a summary of UW-Stout employees spending impacts. Employment Labor Income Output Total Direct 404 9,177,049 30,859,296 Table 7 Payroll Impact combined Total Indirect Total Induced 71 70 1,879,221 1,623,418 5,679,061 5,529,363 Total 545 $12,679,688 $42,067,720 Multiplier 1.35 1.38 1.36 The total economic activities of UW-Stout payroll lead to creation of additional new jobs. Each UW-Stout employee results in .35 total job creation, which means for every FTE employee there is .35 employment. These created jobs generated a total of almost $12.7 million dollars of labor income, yielding $ 760,781 to Wisconsin income tax revenue. Moreover, the purchases of UW-Stout employees of goods and services contribute more than $42.1 million to the local economy and yielding $2.3 million sales tax revenue. The jobs created, earned income (by these created jobs) and the total contribution would have not be realized without the presence of UW-Stout employees. In the fiscal year 2005-06 UW-Stout employees’ disposable income was almost $34.8 million. NorthStar Inc. in its 2002-03 report categorized UW-Stout employees’ expenditures from their disposable income in four industry classes: Private Business, Households, Not-for-Profits, and Government. Applying the same percentage share as in NorthStar Inc. yields industry shares of UW-Stout employees spending which is displayed in Table 8. 20 Table 8 UW-Stout Employees' Disposable Income by Category Industry Sector Disposable Income Percent of Total Private Business 28,496,168 81.9 Households 208,763 0.6 Not-for-Profits 1,182,991 3.4 Government 4,905,934 14.1 Total $34,793,856 100 UW-Stout employees spent almost $28.5 million at local businesses, approximately $1.2 million is given to non-profit organizations and about $5 million to government agencies. Among the sectors that are affected by UW-Stout employees spending are the following: agriculture (dairy and meat), real estate, wood windows and door manufacturing, sanitation manufacturing, plastic plumbing fixtures, glass and glass products, general merchandise stores and whole sale trade, insurance companies, postal services, banking, food and beverage stores, gasoline stations, furniture and home furnishing stores, architectural services, personal care services, legal services, travel agencies, employment services, veterinary services, childcare services, hotel and motels, sporting and athletic vendors, fitness and recreational sport centers, motor vehicles and parts dealers and automotive repairs. 3. Student Expenditures College costs and additional expenditures vary depending on where a student lives during the academic year - at home with parents or relatives, in campus housing (residence halls), or off campus. The costs of attending UW-Stout in the 2005-06 academic year are presented in Table 9. 21 Table 9 Cost of Attendance at UW-Stout for 2005-05 Academic Year Students Living …on Campus … with Parents …off-Campus Tuitions and Fees* $4,692 $4,692 $4,692 Books and Supplies** 314 314 314 4,572 Room and Board** 1,758 2,820 1,758 Transportation** 720 720 720 Other expenses** 1,666 1,666 1,666 Total $11,964 $9,150 $11,970 Total living expenses*** $6,958 $4,144 $6,964 *Total academic student fees ($39,069,622)/headcount (8,327)=$4,692/student **Source:http://www.uwstout.edu/bpa/ir/factbook06.pdf ***Living expenses excluding tuition and fees, and books and supplies To avoid double counting, expenditures on fees, books and supplies are excluded since these payments represent sources of revenue to the university. Based on numbers produced by the UW-Stout Housing, 67 percent of the 8,327 students enrolled in the 2005-06 academic year lived off campus and/or commuted and 33 percent lived in the dorms. Numbers compiled by this study do not distinguish between those students living with their parents or relatives and those living off campus on their own. Thus, assuming all students living off campus spent the “average” of the two possible classifications -living with their parents or relatives and living off campus on their own- each student spent an average of $5,554 while each student living on campus spent an average of $6,958. Based on these estimates, the estimated total spending of UW-Stout students for the 2005-06 school year was equal to $50.14 million. The impact analysis shows that the $50.14 million spent by UW-Stout students produced a total effect of $79.7 million in terms of total output. The total effect in terms of labor income created amounted to $55.53 million. Student expenditures supported a total of 1,578 jobs in Dunn County. The employment multiplier, derived by dividing total jobs by the number of direct jobs, is 1.2. Table 10 displays a summary of student spending impacts. 22 Employment Labor Income Output Total Direct 1,232 46,256,788 50,144,960 Table 10 Students Impact Total Indirect Total Induced 171 175 4,635,046 4,635,050 14,799,055 14,799,060 Total 1,578 $55,526,884 $79,743,075 Multiplier 1.28 1.20 1.59 The total economic activities of UW-Stout students lead to creation of additional new jobs; UW-Stout student supported a total of 1,578 jobs in Dunn County. These created jobs generated a total of almost $55.53 million dollars of labor income, yielding $ 3.3 million to Wisconsin income tax revenue. Moreover, the purchases of UW-Stout students of goods and services contribute to $79.7 million to the local economy and yielding $4.33 million sales tax revenue. Among the sectors that are directly affected by UW-Stout students spending are the following: cheese manufacturing, soft drink and ice cream manufacturing, breweries, stationary and related product manufacturing, gas stations, automatic vending, commercial laundry and dry cleaning machinery, health and personal care stores, clothing and clothing accessories stores, miscellaneous store vendors, newspaper publishers, motion picture and video rental, telecommunications, travel management and reservation services, food services and drinking places, car washes, automotive repair and maintenance, other personal services, and used and secondhand goods. 4. Visitors Expenditures Estimating visitors spending continuously poses a challenging task. One common method is to simply use some estimated percentages of the university budget to infer their contributions, though this method is not always accurate and does not capture the unique nature of students’ and the university activities. To accurately accomplish this task extensive surveys are needed to accounts for headcount and spending patterns per event, which is prohibitively expensive. Therefore, this study will use the recommended expenditures per visitor per day as prescribed by Minnesota IMPLAN Group, Inc. These expenditures are listed in Table 11. 23 Table 11 Spending by Category Category Beverage Snack food Parking Auto Gas Meals from a restaurant Hotels Miscellaneous Spending per Visitor Per Night… Total spending w/Hotel Total spending w/out Hotel Spending Per Visitor Per Day $2.25 $4.00 $2.00 $15.00 $24.00 $65.00 $10.00 $122.25 $57.25 For the beverage category it is recommended to be $.75 with three beverage drinks a day, snack at $2 twice a day, and meals at $8 three times a day. Thus, total spending per day per visitor with hotel/motel stay is $122.25 and without hotel stay is $57.25.2 Miscellaneous expenditures account for souvenirs and other personal items. Spending and purchases of such items may depend on the nature of the visitors if they were business visitors or otherwise. This study estimated total visitor’s spending by events held on campus. As such, this study recognizes five evens, including, move-in and-out days, graduation commencements, athletic events, career conference visitors, and, visitors to students, faculty and official business travelers destined to do business with UW-Stout. To estimate the number of family members that help students move in and out of their dormitories (not accounting for family help extended to students who live offcampus) this study used the number of students in resident halls and assumed two family members per student as a proxy; 277.5 students (it is the average of the fall and spring residents, since students need help move-in in the fall and move-out at the end of spring semester). Assuming it is a one-day trip, total spending is $524,570. Graduation commencement is held twice during the academic year; the first is held at the end of fall semester and the second is at end of the spring semester. Total NorthStar Economics, Inc. assumed that total expenditures by visitors for “in-town stay” and a “oneday” visit to be $174 and $47 per day per visitor, respectively. 2 24 number of graduates is 1,351 with 6.2 family members and 9.9 peers attending two commencement ceremonies, therefore the average is 8.05 visitors per graduate.3 Assuming it is a two night stay, total estimated spending from graduation ceremony is $5.3 million. Visitors to UW-Stout employees are assumed to be three visitors per FTE employee (974) with two night stay, the estimated spending by employees visitors is $714,429. The number of visitors per FTE student (7,199) is assumed to be two with two night stay, total spending is $3.5 million. The total estimated spending by visitors for the purpose of doing business with UW-Stout is more than $5.6 million; it is assumed by NorthStar, Inc., that for every million dollar of university revenue the number of visitors is 331, with a conservative daily spending of $122.25 for 7.7 days. Therefore, the total estimated visitors (to employees, students and business travelers) direct spending is $9.8 million. Athletic events includes home-games for baseball, basketball, cross county, football, gymnastics, hockey, indoor and outdoor track, soccer, softball, tennis and volleyball. Using Athletic tickets sold as a proxy, almost 42,000 people attended UW-Stout home-game athletic events. This study assumes 20 percent of the attendees were from outside the county, thus the estimated spending by these visitors is $1.02 million.4 Career Services hosts Career Conference each October providing recruiters/ companies an opportunity to meet informally with students to share company information and discuss career options. Also, recruiters may come back for a second interview as a follow up on candidates. It is a three day event with an average of three interviewers per potential employer. It is reported by career services that 1,406 employers were present on-campus in October 2005. For the second interview, per employer presence is assumed to be two interviewers staying for two nights. This study adopted the number of successful placements as a proxy for the second on3 Source: UW-Stout’s Economic Contribution to the Region, Dennis K. Winters, NorthStar Economics, Inc. 200203. 4 NorthStar assumed 50 percent were from out of the county attendees. 25 campus interview; there were 281 placements. The total estimated spending by employers for the two events is $1.55 million. Table 12 and Figure 3 summarize the above discussion. Table 12 Visitors Spending by Function Expenditures by Function Expenditures occurred during Move-in-out Days Graduation Ceremony Visitors Visitors to Employees, Students and Business on Campus Athletic Events Career Conference Visitors Total Spending Figure 3 Visitors Expenditure by Category Total Dollars Percentage 524,570 2.9% 5,318,144 29.1% 9,845,107 53.9% 1,026,900 5.6% 1,546,581 8.5% $18,261,301 100.0% Expenditures occurred during Move-in-out Days Graduation Ceremony Visitors Visitors to Employees, Students and Business on Campus Athletic Events Career Conference Visitors The largest estimated spending percentage belongs to the visitors (to employees, students and business); second category is the two graduation commencements attendees, followed by career conference and athletic events visitors. The smallest estimated spending is during the “move-in-out days”. The total estimated spending by all visitors (for all five categories) is $18.3 million. The impact analysis was done on total expenditures by category listed in Table 11 and the result of this analysis is displayed in Table 13. Employment Labor Income Output Total Direct 373 4,909,157 15,840,253 Table 13 Visitors Impact Total Indirect Total Induced 36 46 1,137,888 1,223,051 3,467,214 3,905,419 Total 455 $7,270,096 $23,212,886 Multiplier 1.22 1.48 1.47 The total economic activities of UW-Stout visitors lead to creation of new jobs in the local economy. Each UW-Stout visitor results in .22 total job creation of 455 jobs.5 These created jobs generated a total of almost $7.2 million dollars of labor income, yielding $436,205 increase in Wisconsin income tax revenue. Moreover, the purchases of UW-Stout visitors of goods and services contributed to $23 million to 5 These jobs could be on a temporary base, but nevertheless, Dunn County experienced increase in job creation during the aforementioned events. 26 the local economy and yielded $1.3 million sales tax revenue. Among the industries that are directly affected by the visitors are the hotel and motel industry, food services and drinking places, soft drink and ice manufacturing, and confectionery manufacturing. 5. Impact Summary Tables Table 14 shows a summary of impacts that the university and its auxiliaries, payroll, students and visitors expenditures had on local economy in 2005-06 academic year. Table 14 Impact Data Summary of Employment Impact for All Spending Categories Total Direct Total Indirect Total Induced University and Auxiliaries Expenditures Payroll Students Expenditures Visitors Expenditures 1,128 404 1,232 373 6 71 171 36 Total 3,137 285 Total Multiplier 222 70 175 46 1,357 545 1,578 455 1.20 1.35 1.28 1.22 513 3,935 1.25 Summary of Labor Income Impact for All Spending Categories Total Direct Total Indirect Total Induced University and Auxiliaries Expenditures Payroll Students Expenditures Visitors Expenditures $39,157,952 $9,177,049 $46,256,788 $4,909,157 $166,568 $1,879,221 $4,635,046 $1,137,888 Total $99,500,946 $7,818,723 Total Multiplier $5,096,806 $1,623,418 $4,635,050 $1,223,051 $44,421,326 $12,679,688 $55,526,884 $7,270,096 1.13 1.38 1.20 1.48 $12,578,325 $119,897,994 1.20 Summary of Output Impact for All Spending Categories Total Direct Total Indirect Total Induced University and Auxiliaries Expenditures Payroll Students Expenditures Visitors Expenditures $49,556,015 $30,859,296 $50,144,960 $15,840,253 $512,259 $5,679,061 $14,799,055 $3,467,214 Total $146,400,524 $24,457,589 27 Total Multiplier $17,471,736 $5,529,363 $14,799,060 $3,905,419 $67,540,010 $42,067,720 $79,743,075 $23,212,886 1.36 1.36 1.59 1.47 $41,705,578 $212,563,691 1.45 The main contributor to employment in the local economy is expenditures by UW-Stout employees’ expenditures followed by students and visitors’ expenditures. In terms of labor income, expenditures by the visitors followed by payroll are the main source of increase in labor income in Dunn county. The main contributor to local output is expenditures by students followed respectively by visitors and the university spending and payroll. The relative contribution of each segment is illustrated in Figure 4. Figure 4 Relative Contribution by Category Category Visitors Expenditures Students Expenditures Total Labor Income Total Output Total Employment Payroll University and Auxiliaries Expenditures 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Percentage It is useful to conceptualize the total economic impact of UW-Stout by considering what would happen if the university was not located within Dunn County. Total local output would decrease by about $212.6 million, labor income would decrease by $119.9 million, and employment will be 3,935 smaller. 6. UW-Stout Direct Spending and Impact In 2005-06 academic year the University of Wisconsin – Stout contributed to the local economy by more than $146.4 million, the university related expenditures accounts for $49.5 million in total direct impact, employees’ payroll accounts for 28 $30.9 million, students expenditures accounts for $50.1 million and visitors accounts for $15.8 million. Table 15 displays economic contribution by each actor. Recipients from the total direct spending are private businesses, households, non-profit organizations and the local government. The impact of total direct spending is the largest for private businesses, followed by local government. Figures 5 and 6 depict contributors and recipients shares. Table 15 UW-Stout Direct Economic Contribution and Recipient Shares Contributor University Payroll Student Expenditures Visitor Expenditures $49,556,015 $30,859,296 $50,144,960 $15,840,253 Total $146,400,524 Recipient Private Businesses Households Non-Profit Organizations Local Government $133,370,877 $439,202 $3,806,414 $8,784,031 Total $146,400,524 Figure 5 Contributor Share Figure 6 Recipient Share Inst it ut ion Privat e Businesses Payroll Households St udent Expendit ures Non-Prof it Organizat ions Visit or Expendit ures Local Government The students contribution accounts for 34.3 percent, the university contribute 33.8 percent followed by payroll contribution which accounts for 21.1 percent and visitors contributions amounts to 10.8 percent. Private businesses are the biggest 29 recipient which accounts for 91.1 percent followed by local government, non-profit organizations and households; 6, 2.6, and .3 percent respectively. Among the businesses and industries that benefited from UW-Stout total direct spending are the following: agriculture, forestry, fish and hunting, mining, utilities, constructions, manufacturing, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing, retail trade, information, finance and insurance, real estate, administrative and waste services, educational services, health and social services, entertainment and recreation, accommodation and food services, other services and government. The impact of total contribution of UW-Stout on the local economy is displayed in Table 16.6 Table 16 UW-Stout Total Output Impact University Payroll Student Expenditures Visitor Expenditures Total $140,739,083 $73,445,124 $116,336,307 $36,749,387 $367,269,901 The total economic contribution of UW-Stout to the local economy is $367.2 million, with 38 percent of total impact is attributed to the university, 32 percent is credited to student expenditures, 20 and 10 percent comes from employees payroll and visitors respectively. IV. Concluding Remarks This study analyzed the monetary exchanges between four actors; the university as employer and demander for goods and services, its employees, students and visitors for the 2005-06 academic year. It does not quantify the long run affects of the university on Menomonie and local economy in terms of its intrinsic value of 6 NorthStar Inc. used multipliers of 2.84 for the university, 2.38 for payroll, 2.32 for both student and visitor spending. 30 increased diversity awareness and culture, or the increase in social capital and sense of scholarship. It does not quantify the increase demand for amenities and specialized services, the increase in property value, the potential increase in local wages and the potential increase in proprietor income. It does not capture the increase in research funding outside the university, the increase in “know-how”, the productivity increase of the human capital and does not consider the impact of Poly Technical designation. The latter may prove to be a driver force in attracting new businesses and industries to the region in the long run. To infer the short run economic impact of the university on local economy, this study utilized conservative assumptions and narrow restrictions to reduce the error margins in the predictive models. This was a necessary step to draw realistic conclusions from the aggregate reports. Some modifications to the data used were needed; however sound attempts were made to eliminate double counting and inaccuracies. Because Dunn County is surrounded by Eau Claire, St. Croix, Chippewa, Polk and Pierce counties, an impact analysis including these counties would result in an estimated contribution that would be much larger since it reduces leakages from trade flow accounts and increase the multiplier effects by a factor of 2.09. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that the university is major contributor to the local economy - it is the second largest employer in Dunn County following Wal-Mart Associates Inc. In 2005-06 academic year the University of Wisconsin-Stout contributed more than $367 million to Dunn county economy and more than $386 million to the state of Wisconsin economy.7 7 Total direct and taxes contributions. 31 Reference: Dunn County Workforce Profile: http://dwd.wisconsin.gov/oea/cp_pdf/2006/d033cpw.pdf IMPLAN Data and Software. 2004. Minnesota IMPLAN Group, Inc., IMPLAN System, 1725 Tower Drive West, Suite 140, Stillwater, MN 55082 www.implan.com Measuring Bowling Green State University’s Impact on Ohio’s Economy, Michael C. Carroll, Bowling Green State University. Stout Technology Park: http://www.uwstout.edu/stp/about/ Tax Foundation: http://www.taxfoundation.org/taxdata/show/228.html The Economic Impact of California State University, Fresno on the San Joaquin Valley’s Economy, Dr. Antonio Avalos, Department of Economics, California State University, Fresno, 2006. University of Wisconsin-Stout, Office of Budget, Planning and Analysis, http://www.uwstout.edu/bpa/opbudget/yereview/yebr06.doc University of Wisconsin-Stout, Office of Budget, Planning and Analysis, Fact Book: http://www.uwstout.edu/bpa/ir/factbook06.pdf University of Wisconsin System, Annual Financial Report-2004, http://www.uwsa.edu/fadmin/finrep/afr04.pdf University of Wisconsin System, Office of Budget and Planning, http://www.uwsa.edu/budplan/annualOpBudget.htm University of Wisconsin System, Office of Policy Analysis & Research, Student Statistics Reports, http://www.uwsa.edu/opar/ssb.htm U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey - 2005, http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=ACS UW-Stout’s Economic Contribution to the Region, Dennis K. Winters, NorthStar Economics, Inc. 2002-2003. Wisconsin Department of Revenue, http://www.dor.state.wi.us/faqs/pcs/taxrates.html#txrate2 32