HISTORY OF SEMIOTICS

Kesadaran akan semiotika diawali oleh Augustine (c.397AD) dan Poinsot, lalu

dilanjutkan John Locke, in 1690, dan Charles Sanders Peirce, yang menemukan kategori

semiotik, realisme dan idealisme (1867-1914).

1. The Ancient World and Augustine

Augustine merupakan orang pertama yang mengemukakan pendapat bahwa signum

merupakan alat atau cara yang umum digunakan untuk melakukan berbagai jenis dan

tingkat komunikasi. Pandangan itu pada zamannya dianggap mengejutkan karena dalam

dunia filsafat Yunani atau Romawi kuno yang didominasi oleh filsafat itu tidak ada

satupun pandangan mengenai tanda yang sama seperti yang kita yakini saat ini. Akar kata

"seme-" tentu saja berasal dari Yunani, tetapi dalam naskah Yunani sendiri pandangan

mengenai tanda terbagi dua, yaitu antara Semeion/Nature di satu sisi dan

Symbolon/Culture. Plato dalam Cratylus (c.385BC), juga Aristototeles pada keseluruhan

karyanya termasuk Perihermenias [c.330BC: 16-20a; cf. Eco et al. 1986: 66-68], dan

Boethius [esp. inter 511-513AD] memperkuat kecenderungan munculnya pendapat

Augustine mengenai kesatuan tanda (doctrina signorum).

Selain Augustine, terdapat pula kaum Stoics, yang dalam debatnya dengan Epicureans

mengembangkan teori tanda yang cukup lengkap tetapi yang tersisa hanya sebagian kecil

yang disampaikan secara terpisah-pisah oleh lawan-lawannya, terutama Sextus Empiricus

(c.200). Eco, Lambertini, Marmo, dan Tabarroni (1986: 65-66) mengatakan bahwa

Augustine merupakan orang yang pertama kali mengusulkan istilah semiotika umum

(general semiotics), yaitu ilmu atau doktrin umum mengenai tanda.

2. The Latin World

Dalam perkembangan kesadaran akan semiotika, William of Ockham (i.1317-1328),

walaupun menolak para ahli logika, menerima definisi Augustine bahwa setiap tanda

merupakan penghubung atau kendaraan untuk menuju sesuatu yang immateril, yaitu isi

yang disignifikasi oleh tanda itu yang tidak dapat dipersepsi. Keberatan William atas ahli

logika berakar dari diambilnya tanda dari luar seperti kata-kata dan isyarat dan cara

bagian dalam untuk mengetahui seperti citra dan gagasan sebagai bagian dari perspektif

tanda.

Penolakan atas adanya hubungan antara tanda dengan makna yang dapat dipersepsi yang

telah lama berkembang terjadi saat Ockham tinggal Paris dan karena perkenalannya

dengan konsep kealamiahan tanda (signum naturale). Petrus d'Ailly (c. 1372)

membedakan cara internal (signa formalia) dan cara eksternal untuk mengetahui (signa

instrumentalia), sedangkan apa yang diketahui dan apa yang dirasakan dimiliki bersama

oleh masyarakat. Williams (1985a: xxxiii) mengatakan bahwa kontroversi dalam

semiotika yang diawali sekitar abad ke 17 berkisar pada pertanyaan apakah tanda hanya

melibatkan apa yang dapat dipersepsi. Namun menurut William lebi penting adalah

menjadikan pikiran dan kata-kata ke dalam perspektif doktrin tanda.

3. The Iberian Connection

Dominicus Soto (1529, 1554) pada masa awal studinya di Paris tidak menyetujui

hubungan antara keberadaan tanda dan fungsi aktifnya dalam pengalaman dengan

kendaraan yang dapat dipersepsi sebagai tanda sehingga menimbulkan pertanyaan

mengenai ketergantungan obyektivitas saat tanda berfungsi. Fungsi tanda hanya sebatas

apa yang dapat dilihat dan dialami langsung sebagai sebuah obyek. (Williams 1985a:

xxxi-xxxii):

Pada umumnya, sejak jaman kuno hingga saat ini, tanda dilihat sebagai topeng Janus

(mask of Janus), memiliki dua wajah, dan bersifat relatif atas kekuatan kognitif beberapa

organisma di satu sisi dan atas isi petanda di sisi lain. Relativitas itulah yang

menyebabkan tanda menjadi sebuah tanda. Dalam kaitan ini, tanda dapat berfungsi dari

dalam (from within) kekuatan kognitif suatu organisma dan tanda yang berfungsi

mempengaruhi kekuatan itu dari luar (from without). Pembedaan itu mempertanyakan

hakekat relativitas? Pertanyaan itu dijawab John Poinsot dalam Treatise on Signs

(1632a). Para ahli pra-semiotik realis atau paradigma idealis gagal mengapresiasi bahwa

gagasan merupakan tanda sebelum menjadi obyek kesadaran kita. Dalam pandangan

mereka, tanda hanya dapat memberi akses atas hakekat sesuatu hanya sebatas apa yang

dapat disampaikan oleh tanda. was itself anomalous in terms of previous traditions as

well as in terms of what it anticipated.

The decisive development in this regard was the privileged achievement of John Poinsot,

a student with the Conimbricenses, and the successor, after a century, to Soto's own

teaching position at the University of Alcalá de Henares. With a single stroke of genius

resolving the controversies, since Boethius, over the interpretation of relative being in the

categorial scheme of Aristotle, Poinsot (1632a 117/28-118/18, esp. 118/14-18, annotated

in Deely 1985: 472-479) was able to provide semiotics with a unified object conveying

the action of signs both in nature virtually and in experience actually, as at work at all

three of the analytically distinguishable levels of conscious life (sensation, perception,

intellection). By this same stroke he was also able to reconcile in the univocity of the

object signified the profound difference between what is and what is not either present in

experience here and now or present in physical nature at all (Poinsot 1632a: Book III).

Poinsot was able to reduce to systematic unity Soto's ad hoc series of distinctions, as he

put it in his first announcement of the work of his Treatise ("Lectori", 1631; p. 5 of the

Deely 1985 edition), and thereby to complete the gestation in Latin philosophy of the first

foundational treatise establishing the fundamental character of, and the ultimate

simplicity of the standpoint determining, the issues that govern the unity and scope of the

doctrine of signs. Unfortunately, because he so skillfully embedded his Tractatus de

Signis within a massive and traditional Aristotelian cursus philosophiae naturalis, he

unwittingly ensured its slippage into oblivion in the wake of Descartes' modern

revolution. Three hundred and six years would pass between the original publication of

Poinsot's Treatise on Signs and the first frail appearance of some of its leading ideas in

late modern culture (Maritain 1937-1938, discussed in Deely 1986d).

4. The Place of John Locke

Coincidentally, Poinsot achieved his Herculean labor of the centuries in the birth year of

the man whose privilege it would be, while knowing nothing of Poinsot's work, to give

the perspective so achieved what was to become its proper name. Thus, 1632 was both

the year John Locke was born and the year that Poinsot's treatise on signs was published.

The name-to-be for what both Locke and Poinsot and, later Peirce also, called "the

doctrine of signs"—an expression of pregnant import in its own right, as Sebeok (1976a:

ix) was first to notice (elaborated in Deely 1978a, 1982b, 1986b inter alia)—was

proposed publicly fifty-eight years later, in 1690, in the five closing paragraphs (little

more than the very last page) of Locke's Essay concerning Humane Understanding.

The principal instigation that Locke himself wrote in reaction against, but along very

different lines from what he would end by proposing for "semiotic", was the Cartesian

attempt (1637, 1641) to claim for rational thought a complete separation from any

dependency on sensory experience.

The irony of the situation in this regard was that Locke's principal objections to Descartes

were not at all furthered by the speculative course he set at the beginning and pursued

through the body of his monumental Essay concerning Humane Understanding of 1690.

Instead, he furthered the Cartesian revolution in spite of himself; deflected the brilliant

suspicions of Berkeley (1732); fathered the cynical skepticism of Hume (1748);47 and

laid the seeds of overthrow of his own work in concluding it with the suggestion that

what is really needed is a complete reconsideration of "Ideas and Words, as the great

Instruments of Knowledge" in the perspective that a doctrine of signs would make

possible. The consideration of the means of knowing and communicating within the

perspective of signifying, he presciently suggested, "would afford us another sort of

Logick and Critick, than what we have hitherto been acquainted with". It was for this

possible development that he proposed the name semiotic.

The antinomy between the actual point of view adopted at the beginning for the Essay as

a whole and the possible point of view proposed at its conclusion (Deely 1986a) is, for

semiotic historiography, an object worthy of consideration in its own right.

It remains that to Locke goes the privilege and power of the naming. If today we call the

doctrine of signs "semiotic" and not "semiology", it is to the brief concluding chapter XX

in the original edition of Locke's Essay that we must look for the reason—there, and to

the influence this chapter exercised on the young American thinker, Charles Sanders

Peirce, who read the Essay but made of its conclusion a substantial part of his philosophy

and lifework from 1867 onward.

5. Ferdinand de Saussure, Charles S. Peirce, and John Poinsot

Contemporaneously with Peirce, and independently both of him and of Locke, Ferdinand

de Saussure was also suggesting that the doctrine of signs was a development whose time

had come. For this development he proposed a name (i.1911-1916: 33):

We shall call it semîology (from the Greek semeion, 'sign'). It would teach us what signs consist of and

what laws govern them.

While recognizing that, inasmuch as "it does not yet exist, one cannot say what form it

will take", Saussure wished to insist that the prospective science in question is one that

"has a right to existence" and a place "marked out in advance". It will study "the life of

signs at the heart of social life" and be "a branch of social psychology". "The laws that

semiology will discover" are, accordingly, the laws governing "the totality of human

phenomena", or culture in its contrast with nature.

We see then that Saussure's intuition was fatally flawed in its original formulation. He

placed on his intuition of the need for a science of signs the fatal qualification of viewing

it as a subordinate (or "subaltern") rather than as an architectonic discipline respecting the

whole of human belief, knowledge, and experience, as we have seen its internal

requirements dictate. He further compromised his proposal for the enterprise by making

of linguistics "le patron gnéérale de toute sémiologie", raising the "arbitrariness of signs"

into a principle of analysis for all expressive systems. Thereby he obscured the much

more fundamental interplay of the subjectivity of the physical environment and the

subjectivity of the cognizing organism in the constitution of objectivity for Umwelten in

general and the human Lebenswelt in particular, whereby, in the latter case, even the

linguistic sign in its public functioning becomes assimilated from the start to a natural

form, as far as its users are concerned.

The duality of signifiant and signifié, in a word, lacked the thirdness whereby the sign in

its foundation (and whether or not this foundation be essentially arbitrary or "stipulated")

undergoes transformation into first an object and then into other signs. The dynamics of

the process linking semiosis in culture with semiosis in nature, and making one the

extension of the other in an ongoing spiral of interactions, needs to be brought in. But, for

that, the framework needs to be radically reformulated. As far as the contemporary

establishment of semiotics goes, it was the privilege of Charles Sanders Peirce to provide

just such an alternative framework under the influence of Locke's suggestion.

Let us look with some care at what Peirce did with Locke's suggestion, and see if we can

see with something of dispassion "Why", as Short put it (1988), "we prefer Peirce to

Saussure" today. We will see at the same time something of the doctrinal convergence

Peirce, working with contemporary and modern materials, achieves with the foundational

synthesis of a doctrine of signs distillated by Poinsot from the materials of Greek

antiquity and the Latin middle age.

Beginning with his "New List of Categories" in 1867, and continuing until his death in

1914, semiotic in this broadest sense of the study of semiosis surrounding, as well as

within, the human world provided the thrust underlying and the unity for a substantial

part, and perhaps even for the whole, of Peirce's philosophy.48

At the same time, even in the "New List of Categories" as originally drafted, it is fair to

say that Peirce labored overly under the influence of Kant as Master of the Moderns—

that is to say, between the horns of the dilemma set by the (false) dichotomy of the

realism versus idealism controversy. Since, as I think, semiotic in principle and by

right—the jus signi, let us say—begins by transcending the terms of this controversy, it is

not surprising that Peirce had such a time of it whenever he succumbed to the temptation

to try to classify his own work in realist-idealist terms. Assuming naturally the terms of

the controversy as it had developed over the course of modern thought, he only gradually

came to critical terms with the fact that semiotic as such is a form neither of realism nor

of idealism, but beyond both.

As a disciple of Kant in early life, Peirce labored at the impossible task of establishing

the complete autonomy of the ideal/mental from what is individually existent in nature. In

later life he concluded that this erroneous quest had vitiated modern philosophy (1903:

1.19-21). Significant of this evolution of his thought is the fact that in Peirce's later

philosophy his supreme category of Thirdness changed from representation in 1867 to

triadic relation as common to both representations and to laws existent in nature (c.1899:

1.565).

By his Lowell Lectures of 1903, and even already in his c. 1890 "Guess at the Riddle", it

is clear that Peirce was well on the way to taking his categories of semiosis properly in

hand and was marking out a course of future development for philosophy (as semiotic)

that is nothing less than a new age, as different in its characteristics as is the "realism" of

Greek and Latin times from the idealism of modern times in the national languages.

In his "Minute Logic" (c.1902a: 1.203-272) we have a lengthy analysis of what he calls

"ideal" or "final" causality. He assimilates these two terms as descriptions of the same

general type of causality (ibid.: 1.211, 227). But, in successive analyses (ibid.: 1.211,

214, 227, 231; and similarly in 1903: 1.26), it emerges that causality by ideas constitutes

the more general form of this sort of explanation, inasmuch as final causality, being

concerned with mind, purpose, or quasi-purpose, is restricted to psychology and biology

(c.1902a: 1.269), whereas ideal causality in its general type requires as such neither

purpose (1.211) nor mind nor soul (1.216: cf. the analysis of Poinsot 1632a: 177/8178/7).

Now Peirce identifies this ideal causality with his category of Thirdness, the central

element of his semiotic (1903: 1.26) and the locus for any account of narrative, or of

"lawfulness of any kind". Thirdness consists of triadic relations (c. 1899: 1.565). In these

triadic relations the foundations specify the several relations in different ways, so that one

relation is specified, for example, as "lover of", and another as "loved by" (1897: 3.466).

Thanks to their specification, triadic relations have a certain generality (c.1902a: 2.92;

1903: 1.26). Signs constitute one general class of triadic relations, and the laws of nature

(which are expressed through signs) constitute the other general class (c. 1896: 1.480).

Signs themselves are either genuine or degenerate. Genuine signs concern existential

relations between interacting bodies and need an interpretant to be fully specified as signs

(c.1902a: 2.92). For the genuine triadic sign relation is a mind-dependent similarity

relation between the object of the existential relation and the existential relation itself as

object for the interpretant (1904: 8.332). For example, words need an interpretant to be

fully specified as signs. Triadic sign relations that are degenerate in the first degree

concern existential relations between interacting bodies but require no interpretant to

make them fully specified as signs. For example, a rap on the door means a visitor, with

no explanation needed. Triadic sign relations that are degenerate in the second degree

concern mind-dependent relations specified by the intrinsic possibility of the objects with

which they are concerned, because these relations cannot vary between truth and falsity

whatever any human group may think, as for example, in the case of mathematics, logic,

ethics, esthetics, psychology, and poetry (1903a: 5.125; 1908: 6.455; c.1909: 6.328).

It is clear that when either science or literature, or anything in between, is considered in a

semiotic framework as comprehensive as this, an exclusive treatment of its processes

from the standpoint of constructed signs simply will not do. We risk being lost in

crossword puzzles of great interest, maybe, but without validity as modes of

understanding the semiosis peculiar to humanity as it extends and links up again with the

semiosis that weaves together human beings with the rest of life and nature.

Thus, the work of Peirce is regarded justly as the greatest achievement of any American

philosopher, and at the same time the emergence of semiotic as the major tradition of

intellectual life today throws the lost work of Poinsot into relief for its original

contribution. Just as the writings of the American philosopher Charles Peirce first

illustrated something of the comprehensive scope and complexity in detail of issues that

need to be clarified and thought through anew in the perspective of semiotic, so did the

Iberian Tractatus de Signis of John Poinsot first express the fundamental character of

these issues in light of the ultimate simplicity of the standpoint determining the semiotic

point of view. The Dean of Peirce scholarship, Max H. Fisch, comments with emphasis in

this regard (1986) that, within its limits, Poinsot's work provides us with "the most

systematic treatise on signs that has ever been written".

Just as semiotics itself appears today as a completely unexpected development within the

traditionally established entrenchments of disciplinary specialization, so does it require a

thorough re-examination of the relation of modern thought in its mainstream

development to Latin times in general and to the Iberian Latin development in particular.

In renewing the history of thought and restoring unity to the ancient enterprise of socalled

philosophical understanding, Poinsot's work occupies a privileged position in the

mainstream of semiotic discourse as we see it developing today. "Poinsot's thought",

Sebeok points out (1982: x),

belongs decisively to that mainstream as the 'missing link' between the ancients and the moderns in the

history of semiotic, a pivot as well as a divide between two huge intellective landscapes the ecology of

neither of which could be fully appreciated prior to this major publishing event.

For the fundamental reason pointed out by Williams (1987a: 480) in observing "that

historical narrative is the only logic capable of situating competing traditions and

incommensurate paradigms in a perspective that not only lends each a higher degree of

clarity on its own terms as well as in relation to the others, but also decides which

paradigms will emerge as victorious", the perspective of semiotic requires of anyone

seeking to adopt and develop it a cultivation also of a sense of how the transmissibility of

the past in anthroposemiosis is an essential constituent and not something at the margins

of present consciousness.

In this way, in particular, semiotics puts an end, long overdue, to the Cartesian revolution

(the collection edited by Chenu 1984 is very helpful in this regard) and to the pretensions

of scientific thought to transcend, through mathematical means, the human condition. The

model for semiotics is rather that of a community of inquirers, precisely because "the

human Umwelt presents us with a continuum of past, present, and future in which

continuity and change, convention and invention, commingle, and of which the ultimate

source of unity is time" (Williams 1985: 274). Thus, the work of Williams (1982, 1983,

1984, 1985-1987, 1987a, 1988) and of Pencak (1987; Williams and Pencak, forthcoming)

in penetrating the traditional field of historiographical study from an explicitly semiotic

point of view, is one of the most essential advances in the developing understanding of

semiotics today.

Eventually, we will see that the doctrine of signs requires for its full possibilities a

treating of history as the laboratory within which semiosis, anthroposemiosis in

particular, achieves its results, and to which it must constantly recur when an impasse is

reached or new alternatives are required. Thirdness, after all, is what history is all about.

6. Jakob von Uexküll

So far, we have seen that the small number of pioneers—in particular, Poinsot, Peirce,

and, to a lesser extent, Saussure—who tried to explore and establish directly the

foundational concepts for a doctrine of signs found the way clogged with an underbrush

of conceptual difficulties rooted in the prevailing thought structures and obstructing the

access to the vantage point from which the full expanse of semiotic might be developed.

Peirce, for this reason (c. 1907a: 5.488), described the pioneer work "of clearing and

opening up" semiotic as the task rather of a backwoodsman.

Once the foundations have been secured, there remains the task of building the edifice

and the enterprise of semiotic understanding, by elucidating at all points the crucial

processes comprising the interface of nature and culture summed up in the term semiosis.

This task, too, is clogged by underbrush accruing from presemiotic thought structures that

must be cut away as semiotics reclaims from previous thought contributions essential to

its own enterprise of reflective understanding.

We have now to see how the history and theory of semiotics includes as well background

figures who, without explicitly understanding their work as semiotic, have made useful

and even decisive contributions toward the recognition of what appears in its full

propriety within the widening vista of semiotics. In the case of thinkers who did not deal

directly, in the sense of with set and conscious purpose, with the notion of semiotic

foundations, the wrestling in areas of semiosic functionings with conceptual difficulties

accruing from obstructive thought structures is made all the more difficult for the want of

an explicit entertainment of an alternative to the prevailing mindsets. In such a case, the

very obstructions risk being incorporated into the creative conceptions themselves. When

this happens, an inevitable degree of distortion results, to the extent that the creative

novelties become assimilated to paradigms exclusive of the foundational clarity and

expanse the perspective of semiotics could eventually provide.

There are thus three classes of what Rauch (1983) calls semiotists: there are the

semioticians, workers who begin from the vantage point and within the perspective of the

sign; there are the pioneers or founding figures of semiotics, the protosemioticians, who

struggled to establish the essential nature and fundamental varieties of possible semiosis;

and there are also, among the ranks of present and past workers of the mind,

cryptosemioticians, who need themselves to become aware of the perspective that

semiotic affords49 or whose work needs to be by others reclaimed and re-established from

within that perspective.50 In particular, oppositions seemingly irreconcilable from the

standpoint of the customary juxtaposition of idealism to realism often admit of

subsumption within a higher synthesis from the vantage of semiotic. In such a way,

apparent contradictions within the history of semiotics need not always remain so at the

level of theory

Here, and by way of concluding our historical sketch, we will deal with the case of one of

the greatest cryptosemioticians of the century immediately following the publication in

1867 of Peirce's "New List of Categories", Jakob von Uexküll. The Umwelt-Forschung

he pioneered (1899-1940) is probably the most important recent illustration of a

cryptosemiotic enterprise transcending, in the direction of semiotic, the limitations it

otherwise imposed upon itself by embracing too intimately the mindset and paradigm

immediately available in the milieu of the time and place.

When we talk of the Umwelt, as we have seen, we are talking about the central category

of zoösemiosis and anthroposemiosis alike. The objective world generated at only these

levels of semiosis finally constitutes, to borrow Toews's felicitous phrase (1987), "the

autonomy of meaning and the irreducibility of experience" to anything that might be

supposed to exist independently of it. This concept, belonging to the biological

foundations that "lie at the very epicenter of the study of both communication and

signification in the human animal" (Sebeok 1976a: x), we owe principally to the work of

Jakob von Uexküll. So it is not surprising that von Uexküll has begun to emerge within

contemporary semiotics as perhaps the single most important background thinker for

understanding the biological conditions of our experience of the world in the terms

required by semiotic.51

Having already shown synchronically how useful this concept is to semiotics, we will

now look at von Uexküll's work diachronically in terms of its "semiotic lag", the

phenomenon wherein the terms used in articulating a newer, developing paradigm

inevitably reflect the older ways of thinking in contrast to which the new development is

taking place, and hence constitute a kind of drag on the development, until a point is

reached whereat it becomes possible to coin effectively a fresh turn of phrase reflecting

precisely the new rather than the old. The new terminology has the simultaneous effect of

ceasing the drag and highlighting what in fact was developing all along (cf. Merrell

1987).

In the case of Jakob von Uexkll, the drag is a consequence of having rooted his biological

theories to an eventually counterproductive degree in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant

(1781, 1787). On the positive side, it was Kant who best focussed thematic attention on

the constructive regularities at work from the side of the subject in establishing the

objects of experience so far as they belong to the phenomenal realm of the appearances of

everyday life. Appreciation of the constructive role of the cognitive powers of the

knowing subject and of that subject's affective shaping of cognitive content in the

presentation through perception of what is known was, to be sure, an essential advance of

philosophical understanding in the matter of dealing theoretically with the origins of

knowledge and the nature of experience in the assessments of belief and practices. The

emphasis on these matters communicated from Kant to von Uexküll was indispensable.

Dispensable was the Kantian failure to deal with the rationale according to which the

constructive elements contributed by the subject—socalled concepts or ideas—are

abductively arrived at as necessary postulates in the first place. This rationale was one of

the several threads in the discussions crucial for epistemology that developed over the

closing Latin centuries—particularly in Iberia—and were lost to the modern development

as it took place, after Descartes, through the Latin filter of Suarez's Disputationes

Metaphysicae of 1597.

In the German and Kantian context—even more, if possible, than in the modern context

generally—the opposition of the terms "subjective" and "objective" is a firmly

established dichotomy whose transparency is self-evident. Within this context, von

Uexküll himself, who, as his son notes (T. von Uexküll 1981: 148), did not think of his

work thematically under the rubric of semiotic, had little alternative to seeing the Umwelt

in opposition to the supposed and so-called objective, and as belonging to the

phenomenal realm in Kant's sense—on the side of the "subjective", that is,

dichotomically conceived in opposition to the supposed "objective".

The want of alternative for von Uexküll himself has resulted in considerable confusion

regarding his work in general (through misplaced associations with "vitalism") and,

specifically, in notorious difficulties in interpreting (or "translating") the key term,

"Umwelt".52 The difficulties are a clue to the real problem.53 As far as semiotics is

concerned, von Uexküll's work needs to be thought through afresh at the level of basic

terminology generally and specifically as regards the extent of reliance placed on the

Kantian scheme for philosophy of mind.

T. von Uexküll, for example, in explaining his father's work for the context of semiotics

today, unwittingly brings out the inconsistency that obtains between an orthodox Kantian

perspective and the perspective of semiotic. According to the son's account (I choose an

example where the inconsistency that runs throughout the account is concisely illustrated

within one short paragraph, T. von Uexküll 1981: 161): on the one hand, "A schema is a

strictly private program" for the formation of complex signs "in our subjective universe";

and, on the other hand, "The schemata which we have formed during our life are

intersubjectively identical" at least "in the most general outlines". But, of course, to speak

of the intersubjective save as a pure appearance, in a Kantian context, is as internally

inconsistent as to speak of a grasping of the Ding-an-sich in that same context (as Hegel

best noted).

The conflict, thus, is between an idealist perspective in which the mind knows only what

it constructs and the semiotic perspective in which what the mind constructs and what is

partially prejacent to those constructions interweave objectively to constitute indistinctly

what is directly experienced and known.

Himself immersed in the Kantian philosophy—that is, the most classical of the classical

modern idealisms—Jakob von Uexküll yet was creating in spite of that immersion,

through a creative intuition of his own, a notion anticipating another context entirely, a

context which had yet to catalyze thematically and receive general acceptance under its

own proper name, to wit, the context of semiotic as the doctrine of signs. He was

inadvertently precipitating a paradigm shift. A formula I applied to Heidegger (1986: 56),

mutatis mutandis (that is, substituting "biologist" for "philosopher" and "from within" for

"against") can be applied to Jakob von Uexkll: among modern biologists he is the one

who struggled most from within the coils of German idealism and in the direction of a

semiotic.

For, unlike Heidegger, who expressly wrestled with reaching an alternative to the existing

paradigms both realist and idealist, von Uexküll embraced a horn of the false dilemma:

he saw himself as merely extending the Kantian paradigm to biology. He did not see that

such an "adaptation" presupposed a capacity of human understanding incompatible with

the original claims Kant thought to establish for rational life by his initiative. In other

words, to apply Kant's paradigm as von Uexküll intended, it was necessary in the

application already to transcend the paradigm—an adaptation of the original through

mutation indeed.

The genuine adoption by a human observer of the point of view of another life form, on

which Umwelt research is predicated, is a-priori impossible in the original Kantian

scheme. Either Umweltensforschung is a form of transcendental illusion, or, if it is

valid—if, for example, von Frisch really did interpret with some correctness the bee's

dance or von Uexküll the toad's search image—then von Uexküll, in extending Kant's

ideas to biology, was also doing something more, something that the Kantian paradigm

did not allow for, namely, achieving objectively and grasping as such an intersubjective

correspondence between subjectivities attained through the sign relation.54

Once it is understood that the classical terms of the subject-object dichotomy are

rendered nugatory within the perspective of a doctrine of signs and that, within this

context, the term "objective" functions precisely to mean the prospectively

intersubjective, in opposition to both terms of the dichotomy classically understood, new

possibilities of understanding are opened up. These possibilities are more in line with

what is at the center of, the original to, von Uexkll's work than could be seen through the

filter of Kantian idealism, which provided at the time the only developed language

available to a scientist of philosophical bent. As "a consistently shared point of view,

having as its subject matter all systems of signs irrespective of their substance and

without regard to the species of the emitter or receiver involved" (Sebeok 1968: 64),

semiotics requires a theoretical foundation equally comprehensive. That foundation can

be provided only by an understanding of the being with its consequent causality and

action proper to signs in their universal role. With all the subdivisions, neither a

perspective of traditional idealism nor of traditional realism has the required expanse.

As semiotics comes of age, it must increasingly free itself from the drag of pre-existing

philosophical paradigms. Beginning with the sign—that is, from the function of signs

taken in their own right within our experience (semiosis)—it is the task of semiotics to

create a new paradigm—its ownand to review, criticize, and improve wherever possible

all previous accounts of experience, knowledge and belief in the terms of that paradigm.

It is thus that the history of semiotics and the theory of semiotics are only virtually

distinct, forming together the actual whole of human understanding as an achievement, a

prise de conscience, in process and in community.

The maxim for that process, accordingly, is the same as the maxim for semiotics itself:

Nil est in intellectum nec in sensum quod non prius habeatur in signum ("There is

nothing in thought or in sensation which is not first possessed in a sign").55 For if the

anthropos as semiotic animal is an interpretant of semiosis in nature and culture alike,

that can only be because the ideas of this animal, in their function as signs, are not limited

to either order, but have rather, as we explained above, the universe in its totality—"all

that wider universe, embracing the universe of existents as a part"—as their object.

References

Back to index

Copyright 1990 John Deely, all rights reserved.

Semiotics: Nature and Machine

http://www.bookrags.com/research/semiotics-este-0001_0004_0/

Semiotics (from the Greek word for sign) is the doctrine and science of

signs and their use. It is thus a more comprehensive system than

language itself and can therefore be used to understand language in

relation to other forms of communication and interpretation such as

nonverbal forms. One can trace the development of semiotics starting

with its origins in the classical Greek period (from medical

symptomatology), through subsequent developments during the Middle

Ages (Deely 2001), and up to John Locke's introduction of the term in the

seventeenth century. But contemporary semiotics has its real foundations

in the nineteenth century with Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) and

Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913), who, working independently of each

other, developed slightly different conceptions of the sign. The

development of semiotics as a broad field is nevertheless mostly based on

Peirce's framework, which is therefore adopted here.

Ever since Umberto Eco (1976) formulated the problem of the "semiotic

threshold" to try to keep semiotics within the cultural sciences,

semiotics—especially Peircian semiotics—has developed further into the

realm of biology, crossing threshold after threshold into the sciences.

Although semiotics emerged in efforts to scientifically investigate how

signs function in culture, the twentieth century witnessed efforts to

extend semiotic theory into the noncultural realm, primarily in relation to

living systems and computers. Because Peirce's semiotics is the only one

that deals systematically with nonintentional signs of the body and of

nature at large, it has become the main source for semiotic theories of

the similarities and differences among signs of inorganic nature, signs of

living systems, signs of machines (especially computer semiotics, see

Andersen 1990), and the cultural and linguistic signs of humans living

together in a society that emphasizes the search for information and

knowledge. Resulting developments have then been deployed to change

the scope of semiotics from strictly cultural communication to a

biosemiotics that encompasses the cognition and communication of all

living systems from the inside of cells to the entire biosphere, and a

cybersemiotics that in addition includes a theory of information systems.

Biosemiotics and Its Controversies

Semiotics is a transdisciplinary doctrine that studies how signs in

general—including codes, media, and language, plus the sign systems

used in parallel with language—work to produce interpretation and

meaning in human and in nonhuman living systems as prelinguistic

communication systems. In the founding semiotic tradition of Peirce, a

sign is anything that stands for something or somebody in some respect

or context.

Taking this further, a sign, or representamen, is a medium for

communication of a form in a triadic (three-way) relation. The

representamen refers (passively) to its object, which determines it, and

to its interpretant, which it determines, without being itself affected. The

interpretant is the interpretation in the form of a more developed sign in

the mind of the interpreting and receiving mind or quasi mind. The

representamen could be, for example, a moving hand that refers to an

object for an interpretant; the interpretation in a person's mind

materializes as the more developed sign "waving," which is a cultural

convention and therefore a symbol.

All kinds of alphabets are composed of signs. Signs are mostly imbedded

in a sign system based on codes, after the manner of alphabets of natural

and artificial languages or of ritualized animal behaviors, where fixed

action patterns such as feeding the young in gulls take on a sign

character when used in the mating game.

Inspired by the work of Margaret Mead, Thomas A. Sebeok extended this

last aspect to cover all animal species–specific communication systems

and their signifying behaviors under the term zoösemiotics (Sebeok

1972). Later Sebeok concluded that zoösemiotics rests on a more

comprehensive biosemiotics (Sebeok and Umiker-Sebeok 1992). This

global conception of semiotics equates life with sign interpretation and

mediation, so that semiotics encompasses all living systems including

plants (Krampen 1981), bacteria, and cells in the human body (called

endosemiotics by Uexküll, Geigges, and Herrmann 1993). Although

biosemiotics has been pursued since the early 1960s, it remains

controversial because many linguistic and cultural semioticians see it as

requiring an illegitimate broadening of the concept of code.

A code is a set of transformation rules that convert messages from one

form of representation to another. Obvious examples can be found in

Morse code and cryptography. Broadly speaking, code thus includes

everything of a more systematic nature (rules) that source and receiver

must know a priori about a sign for it to correlate processes and

structures between two different areas. This is because codes, in contrast

to universal laws, work only in specific contexts, and interpretation is

based on more or less conventional rules, whether cultural or (by

extension) biological.

Exemplifying a biological code is DNA. In the protein production system—

which includes the genome in a cell nucleus, the RNA molecules going in

and out of the nucleus, and the ribosomes outside the nucleus

membrane—triplet base pairs in the DNA have been translated to a

messenger RNA molecule, which is then read by the ribosome as a code

for amino acids to string together in a specific sequence to make a

specific protein. The context is that all the parts have to be brought

together in a proper space, temperature, and acidity combined with the

right enzymes for the code to work. Naturally this only happens in cells.

Sebeok writes of the genetic code as well as of the metabolic, neural, and

verbal codes. Living systems are self-organized not only on the basis of

natural laws but also using codes developed in the course of evolution. In

an overall code there may also exist subcodes grouped in a hierarchy. To

view something as encoded is to interpret it as-sign-ment (Sebeok 1992).

A symbol is a conventionally and arbitrary defined sign, usually seen as

created in language and culture. In common languages it can be a word,

but gestures, objects such as flags and presidents, and specific events

such as a soccer match can be symbols (for example, of national pride).

Biosemioticians claim the concept of symbol extends beyond cultures,

because some animals have signs that are "shifters." That is, the meaning

of these signs changes with situations, as for instance the head tossing of

the herring gull occurs both as a precoital display and when the female is

begging for food. Such a transdisciplinary broadening of the concept of a

symbol is a challenge for linguists and semioticians working only with

human language and culture.

To see how this challenge may be developed, consider seven different

examples of signs. A sign stands for something for somebody:

1. as the word blue stands for a certain range of color, but also has

come to stand for an emotional state;

2. as the flag stands for the nation;

3. as a shaken fist can indicate anger;

4. as red spots on the skin can be a symptom for German measles;

5. as the wagging of a dog's tail can be a sign of friendliness for both

dogs and humans;

6. as pheromones can signal heat to the other sex of the species;

7. as the hormone oxytocin from the pituitary can cause cells in

lactating glands of the breast to release the milk.

Linguistic and cultural semioticians in the tradition of Saussure would

usually not accept examples 3 to 6 as genuine signs, because they are

not self-consciously intentional human acts. But those working in the

tradition of Peirce also accept nonconscious intentional signs in humans

(3) and between animals (5 and 6) as well as between animals and

humans (4), nonintentional signs (4), and signs between organs and cells

in the body (7). This last example even takes special form in

immunosemiotics, which deals with the immunological code,

immunological memory, and recognition.

There has been a well-known debate about the concepts of primary and

secondary modeling systems (see for example Sebeok and Danesi 2000)

in linguistics that has now been changed by biosemiotics. Originally

language was seen as the primary modeling system, whereas culture

comprised a secondary one. But through biosemiotics Sebeok has argued

that there exists a zoösemiotic system, which has to be called primary, as

the foundation of human language. From this perspective language thus

becomes the secondary and culture tertiary.

Cybersemiotics and Ethics

In the formulation of a transdisciplinary theory of signification and

communication in nature, humans, machines, and animals, semiotics is in

competition with the information processing paradigm of cognitive science

(Gardner 1985) used in computer informatics and psychology (Lindsay

and Norman 1977, Fodor 2000), and library and information science

(Vickery and Vickery 2004), and worked out in a general renewal of the

materialistic evolutionary worldview (for example, Stonier 1997). Søren

Brier (1996a, 1996b) has criticized the information processing paradigm

and second-order cybernetics, including Niklas Luhmann's communication

theory (1995), for not being able to produce a foundational theory of

signification and meaning. Thus it is found necessary to add biosemiotics

ability to encompass both nature and machine to make a theory of

signification, cognition and communication that encompass the sciences,

technology as well as the humanities aspect of communication and

interpretation.

Life can be understood from a chemical point of view as an autocatalytic,

autonomous, autopoietic system, but this does not explain how the

individual biological self and awareness appear in the nervous system. In

the living system, hormones and transmitters do not function only on a

physical causal basis. Not even the chemical pattern fitting formal

causation is enough to explain how sign molecules function, because their

effect is temporally and individually contextualized. They function also on

a basis of final causation to support the survival of the self-organized

biological self. As Sebeok (1992) points out, the mutual coding of sign

molecules from the nervous, hormone, and immune systems is an

important part of the self-organizing of a biological self, which again is in

constant recursive interaction with its perceived environment Umwelt

(Uexkull 1993). This produces a view of nerve cell communication based

on a Peircian worldview binding the physical efficient causation described

through the concept of energy with the chemical formal causation

described through the concept of information—and the final causations in

biological systems being described through the concept of semiosis (Brier

2003).

From a cybersemiotic perspective, the bit (or basic difference) of

information science becomes a sign only when it makes a difference for

someone (Bateson 1972). For Pierce, a sign is something standing for

something else for someone in a context. Information bits are at most

pre- or quasi signs and insofar as they are involved with codes function

only like keys in a lock. Information bits in a computer do not depend for

their functioning on living systems with final causation to interpret them.

They function simply on the basis of formal causation, as interactions

dependent on differences and patterns. But when people see information

bits as encoding for language in a word processing program, then the bits

become signs for them.

To attempt to understand human beings—their communication and

attempts through interpretation to make meaning of the world—from

frameworks that at their foundation are unable to fathom basic human

features such as consciousness, free will, meaning, interpretation, and

understanding is unethical. To do so tries to explain away basic human

conditions of existence and thereby reduce or even destroy what one is

attempting to explain. Humans are not to be fitted and disciplined to work

well with computers and information systems. It is the other way round.

These systems must be developed with respect for the depth,

multidimensional, and contextualizing abilities of human perception,

language communication, and interpretation.

Behaviorism, different forms of eliminative materialism, information

science, and cognitive science all attempt to explain human

communication from outside, without respecting the phenomenological

and hermeneutical aspects of existence. Something important about

human nature is missing in these systems and the technologies developed

on their basis (Fodor 2000). It is unethical to understand human

communication only in the light of the computer. Terry Winograd and

Fernando Flores (1987), among others, have argued for a more

comprehensive framework.

But it is also unethical not to contemplate the material constraints and

laws of human existence, as occurs in so many purely humanistic

approaches to human cognition, communication, and signification. Life, as

human embodiment, is fundamental to the understanding of human

understanding, and thereby to ecological and evolutionary perspectives,

including cosmology. John Deely (1990), Claus Emmeche (1998), Jesper

Hoffmeyer (1996), and Brier (2003) all work with these perspectives in

the new view of semiotics inspired by Peirce and Sebeok. Peircian

semiotics in its contemporary biosemiotic and cybersemiotic forms is part

of an ethical quest for a transdisciplinary framework for understanding

humans in nature as well as in culture, in matter as well as in mind.

See Also

Peirce, Charles Sanders.

Bibliography

Andersen, P. B. (1990). A Theory of Computer Semiotics: Semiotic

Approaches to Construction and Assessment of Computer Systems.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bateson, Gregory. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays

in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. San Francisco:

Chandler Publishing. Based on Norbert Wiener's classical cybernetics, a

foundational work that develops the view toward second-order

cybernetics and semiotics.

Brier, Søren. (1996a). "Cybersemiotics: A New Interdisciplinary

Development Applied to the Problems of Knowledge Organisation and

Document Retrieval in Information Science." Journal of Documentation

52(3): 296–344.

Brier, Søren. (1996b). "From Second Order Cybernetics to

Cybersemiotics: A Semiotic Re-entry into the Second-Order Cybernetics

of Heinz von Foerster." Systems Research 13(3): 229–244. Part of a

Festschrift for von Foerster.

Brier, Søren. (2003). "The Cybersemiotic Model of Communication: An

Evolutionary View on the Threshold between Semiosis and Informational

Exchange." TripleC 1(1): 71–94. Also available from

http://triplec.uti.at/articles.php.

Deely, John. (1990). Basics of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Deely, John. (2001). Four Ages of Understanding: The First Postmodern

Survey of Philosophy from Ancient Times to the Turn of the Twenty-First

Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Integrates semiotics as a

central theme in the development of philosophy, thereby providing a

profoundly different view of the history of philosophy.

Eco, Umberto. (1976). A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana

University Press. Foundational interdisciplinary work of modern semiotics.

Emmeche, Claus. (1998). "Defining Life as a Semiotic Phenomenon."

Cybernetics and Human Knowing 5(1): 3–17.

Fodor, Jerry. (2000). The Mind Doesn't Work That Way: The Scope and

Limits of Computational Psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gardner, Howard. (1985). The Mind's New Science: A History of the

Cognitive Revolution. New York: Basic.

Hoffmeyer, Jesper. (1996). Signs of Meaning in the Universe, trans.

Barbara J. Haveland. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. The first and

foundational book of modern biosemiotics.

Krampen, Martin. (1981). "Phytosemiotics." Semiotica 36(3/4): 187–209.

Lindsay, Peter, and Donald A. Norman. (1977). Human Information

Processing: An Introduction to Psychology, 2nd edition. New York:

Academic Press.

Luhmann, Niklas. (1995). Social Systems, trans. John Bednarz Jr. and

Dirk Baecker. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sebeok, Thomas A. (1972). Perspectives in Zoosemiotics. The Hague,

Netherlands: Mouton.

Sebeok, Thomas A. (1992). "'Tell Me, Where Is Fancy Bred?' The

Biosemiotic Self." In Biosemiotics: The Semiotic Web, 1991, ed. Thomas

A. Sebeok and Jean Umiker-Sebeok. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Sebeok, Thomas A., ed. (1994). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics, 2nd

edition. 3 vols. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. One of the most

comprehensive and authoritative works on all aspects of semiotics.

Sebeok, Thomas A., and Marcel Danesi. (2000). The Forms of Meaning:

Modeling Systems Theory and Semiotic Analysis. Berlin: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Sebeok, Thomas A., and Jean Umiker-Sebeok, eds. (1992). Biosemiotics:

The Semiotic Web, 1991. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Stonier, Tom. (1997). Information and Meaning: An Evolutionary

Perspective. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. An important extension of the

information processing paradigm, showing its greatness and limitations.

Uexküll, Thure von; Werner Geigges; and Jörg M. Herrmann. (1993).

"Endosemiosis." Semiotica 96(1/2): 5–51.

Vickery, Brian C., and Alina Vickery. (2004). Information Science in

Theory and Practice, 3rd edition. Munich: Saur. A comprehensive and

important presentation, conceptualization, and use of the information

processing paradigm in library and information science.

Winograd, Terry, and Fernando Flores. (1987). Understanding Computers

and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley.

This complete Semiotics contains 5 words. This article contains 5,653 words (approx. 19 pages

at 300 words per page).

Critical Theory essay on Key Terms in Semiology

©by Elizabeth Faint Doyle

http://www.geocities.com/CollegePark/9349/essay.htm

Semiotic analysis is a way of looking at the world around us in a structured, scientific

way, so that we realise that the signs and symbols we encounter have a culturally

determined basis, rather than occurring naturally through mere coincidence. The concept

of semiotics as a specific tool allowing us to do this emerged only at the beginning of this

century, thanks to the work of the Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles

Sanders Pierce, an American philosopher, although many other cultural theorists have

also contributed to modern understanding of semiotics. Semiotics allows us to study the

technical systems of communication using non-linguistic signals; to study social

communications and can also be used to study signs in the arts and in literature. For this

purpose, there is a specific terminology, five key terms from which will be defined within

this essay - sign, signifier, signified, denotation and connotation; along with references to

texts where these terms have been encountered and examples, to show an understanding

of the basic principles of semiotic analysis.

Signs are the basic tools of semiotics. It has been said by C.S.Pierce, that...

"A sign...is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect..." 1

It is possible to say that anything can be considered to be a sign, an obvious example

being a road sign. When someone encounters a road sign, their reaction to it is usually

unconscious. The person will usually do as the road sign asks, for example, restrict speed

to within 30 miles per hour, without wondering whether they have understood it clearly.

Semiotics demonstrates that although we carry out the action without relating it to the

sign, in fact the sign is culturally determined i.e. one has to learn how to respond to the

stimulus. Following the Saussurian explanation of this phenomenon, we know that a sign

has two parts: the signifier, which in this case would be the actual road sign; and the

signified, the concept of maintaining a speed limit of 30 miles per hour. A sign does not

convey any meaning by itself: the meaning is determined by those who use the sign

system. The sign only has meaning because of its difference from other signs, so one has

to be aware of this to understand any one sign.

So, the signifier is the entity which first catches our attention. If one imagines a sign to be

a coin, then the signifier is the objective, cognitive side of the coin: the logical aspect of

the sign. The signifier is the physical part of the sign, or the spoken word, or the shape

written on paper. A signifier can take any form.

"The fact that the relation between signifier and signified is arbitrary means, then, that

since there are no fixed universal concepts or fixed universal signifiers, the signifier itself

is arbitrary, and so is the signified." 2

Furthermore, it takes no special skill in order to be aware of a sign, either to see the

notice or to hear the word: this is the passive part of the process. The only rule which

must be obeyed in relation to a signified is that everyone within the group using the

specific sign system recognises the same signifier as referring to a certain concept. An

interesting example of a signifier not meaning anything to someone comes from J.M

Barrie's 'Peter Pan':

"'I'll give you a kiss for that if you like,' she said. 'All right,' he said, 'thanks' - and held

out his hand for it. Wendy stared at such ignorance. 'Don't you really know what a kiss

is?' she asked. 'I shall when you give me it,' he replied. She was not sure what to do, but

not wishing to hurt his feelings, she felt in her pocket for something to give, and found

her thimble. 'There,' she said and dropped it into his hand. 'Oh, that's a kiss, is it?' he

responded cheer- fully. 'Now, would you like me to give you one?' 'If you please,' Wendy

replied demurely. expecting it to be a real kiss, in spite of what had just happened, but he

pulled a button off his tunic and gave her that. She saw it was a small acorn. 'Thank you

very much,' she said. 'I'll wear it on a chain round my neck.'" 3

It can be seen from the example that Peter Pan obviously does not know what a kiss is,

and the Concise Oxford Dictionary definition of a kiss is 'a touch with the lips, especially

as a sign of love, affection, greeting or reverence', but Peter is perfectly happy to accept

Wendy's explanation of it. The word 'kiss' is a signifier, and because Wendy offers no

explanation of the real concept of a kiss, but effectively offers a new one, she is showing

the arbitrariness of both the signifier and the signified.

To illustrate the other side of the coin, one must consider the term 'signified'. The

signified is the referent...the concept being referred to by the signifier. As Pierre Guiraud

said:

"A sign is always marked by an intention of communicating something meaningful" 4

and the signified is the active part of the sign from which the meaningful concept is

derived. To refer back to the example of Peter Pan, the concept of a kiss, as Wendy

understands it, is the same concept we as English speakers would understand it - that of 'a

touch with the lips...'. We can relate the dictionary definition to our own experience. The

signified is significant to us because we have kissed and have been kissed. Various

leading characters in the semiotic field have been able to push the notion of the signified

further, such as: Roland Barthes with his 'denotative signified' and 'connotative signified',

which build another level onto the level discussed here and Jacques Derrida's 'central

transcendental signified', which explains that each signified gains meaning from its place

in a bigger system, but these are beyond the scope of this essay, which only aims to show

a basic understanding of the terms.

Denotation can be described in the simplest way as what the sign is actually showing us.

What does one actually see (or hear etc.) when they observe a sign? Imagine the recent

advertisements for the Irish beer 'Kilkenny' (see appendix): what the advertisement shows

is a picture of a man pursing his lips to take a drink from a pint of beer and a legend,

which says 'You never forget your first kiss'. The main title on the advert is 'Kiss the

Kilkenny'. From looking at this advertisement the first thing we have is the denotation,

which is exactly what has just been described - the image of the man taking a drink and

the words appearing around it. The denotation catches our attention and leads us to

examine the sign and derive some message from it - connotation. According to Kaja

Silverman, the notion of describing something as 'denotative' is generally attributed to

Roland Barthes:

"...would be described by Barthes as 'denotative'. The denotative complex yields

immediately to a series of connotative transactions..." 5

A popular television quiz show, 'Catchphrase', (LWT, Fridays 7 p.m.) has its underlying

basis in the denotative / connotative process. The game is played by showing the

contestants graphical images and asking them to describe what they see in terms of a

word or phrase. Having observed the actual picture, they must then participate in a quick

series of mental 'connotative transactions' in order to guess the answer, which leads us

next to define the term 'connotation' before we can analyse it.

Connotation is the process by which we make associations and assumptions based on

previously learned cultural perspectives in relation to the actual stimulus of the denotative

level of the sign. Referring back to the last example, we note that the contestants have to

participate in an active process in order to deduce the correct answer. They have to

observe the denotation in each picture, sift through all the possible connotative answers in

order to arrive at the correct one. A very simple example of the type of question posed is

that of the word 'gum' made up of many small bubble shapes. The contestant is able to

denote that the answer involves the word 'gum' and that bubbles are relevant. The obvious

answer to those of us in late twentieth century western cultures is 'bubble-gum', but the

concept of bubble-gum may mean nothing to other cultures. This process was formulated

by the Danish linguist, Louis Hjelmslev:

"...after the analysis of the denotative semiotic is completed, the connotative semiotic

must be subjected to just the same procedure..." 6

This essay has aimed to show a basic understanding of the principles of semiotic analysis

through the definition of key terms, the use of references, and examples to highlight

important points throughout. A very apt quotation to form the basis of the conclusion

comes from Pierre Guiraud:

"Thus if semiology is to be the science of signs it encompasses all knowledge and all

experience, for everything is a sign: everything is signified and everything is signifier." 7

If everything is sign, signified and signifier, then it is therefore possible to say that

everything is also subject to the denotative and connotative processes: it is the instinct of

human nature to examine both itself and its environment.

Footnotes

1. The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Pierce, ed. Charles Hartshorne and Paul

Weiss (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1931), Vol. II, p. 135. as quoted in The

Subject of Semiotics, p. 14, see bibliography.

2. Saussure, Jonathan Culler, Fontana, London 1986, (2nd edition), p. 23.

3. J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan, The Story of the Play, Eleanor Graham and Edward

Ardizzone, Brockhampton Press, Leicester, 1967, p. 34.

4. Semiology, Pierre Guirard, Routledge, London, 1988, p. 22.

5. The Subject of Semiotics, p.35, see bibliography.

6. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, Louis Hjelmslev, trans. Francis J.

Whitfield, (Madison:Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1969), p. 119, as quoted in The

Subject of Semiotics, p. 26, see bibliography.

7. Semiology, Pierre Guiraud, p. 40, see bibliography.

Bibliography

Aston, Elaine and Savona, George, Theatre as Sign System: A Semiotics of Text and

Performance, Routledge, London 1991.

Culler, Jonathan, Barthes, Fontana, London, 1990.

Saussure, Fontana, London 1986, (2nd Edition).

Easthope, Anthony (Ed), A Critical and Cultural Theory Reader,

Open University Press, Buckingham 1996.

Guirard, Pierre, Semiology, Routledge, London 1988.

Rylance, Rick, Roland Barthes, Harvester Wheatsheaf, London 1994.

Silverman, Kaja, The Subject of Semiotics,

Oxford University Press, New York, 1984.

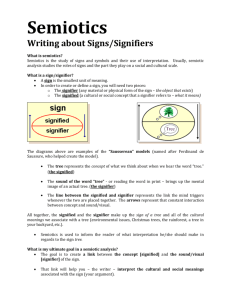

Semiotika, Semiosis, Semiologi: Kata nomina dari studi mengenai tanda dan

pemaknaannya, proses mengaitkan signifieds (petanda) dengan signifiers

(petanda), studi mengenai tanda dan system pemaknaannya.

Tanda: Sesuatu yang bagi seseorang mewakili sesuatu yang lain.

Simbol: Mewakili sebuah obyek seperti bendera, tanda pintu toilet, tanda lalu lintas.

Indeks: Menunjuk ke suatu hal- sebuah indikator seperti mendung pertanda hujan, asap

penunjuk adanya api, dan indeks pada halaman akhir buku yang menunjukkan

halaman pembahasan konsep yang ditunjukannya.

Ikon: Representasi sebuah obyek yang menghasilkan citra mental obyek yang

direpresentasi tersebut. Misalnya, gambar pohon menyebabkan munculnya citra

mental yang sama apa pun bahasa yang digunakan

Signifier atau penanda: Dalam beberapa hal merupakan sebuah pengganti. Kata-kata

baik lisan maupun tertulis merupakan penanda.

Signified atau petanda: Apa yang dirujuk oleh penanda. Ada dua jenis petanda, yaitu:

Konotatif: menunjuk kepada petanda tetapi mempunyai makna yang lebih dalam.

Sebuah contoh diberikan yang Barthes untuk konotasi adalah "pohon" = hijau

mewah, “kursi” = jabatan

Denotatif: petanda yang sebenarnya, hampir mirip dengan definisi

Slippage: Ketika makna berpindah karena sebuah penanda mempunyai tafsiran penanda

lebih dari satu

Wacana: Pesan yang memiliki fungsi komunikatif dan biasanya lebih kompleks dari

tanda yang sederhana.

Tanda mistis: Pesan yang tak pernah dipertanyakan yang memperkuat nilai-nilai

dominant dalam sebuah masyarakat. Pesan-pesan itu tidak menimbulkan pertanyaan atau

berpikir kritis.

Sistem denotatif: Sebuah penanda, petanda dan tanda yang bersama-sama membentuk

sebuah makna.

Sistem semiologis tahap dua: Sistem konotatif yang menggabungkan tanda dari sistem

yang pertama menjadi signifier dari sistem yang kedua.

Taksonomi: Satu jenis analisis struktural dimana ciri-ciri sebuah sistem semiotik

digolongkan.

Eksegesis: Interpretasi isi saja yang mencari makna secara konotatif.

Hermenuetik: Berbeda dengan eksegesis karena hermenutik kurang praktis. Teks

menunda dan bahkan memisahkan diri untuk memnggeser makna melalui slippage atau

skidding.

Readerly text: (from the Pleasure of the Text) Discourse that stabilizes and meets the

expectations of the reader.

Writerly text: is a text that discomforts the reader and creates a subject position for

him/her that is outside of his/her mores or cultural base.

Sign :

A deterministic, functional regularity or stability in a system, also sometimes

called a sign-function. Something, the signifier, stands for something else, the

signified, in virtue of the sign-function. May be either lawful, proper, or symbolic

depending on the presence or absence of motivation. This is, of course, a very

general definition, but it is in the tradition of both semiotics and general systems

theory to think very generally.

Contains: signifier, signified.

Cases: lawful, proper, symbolic.

Synonym: sign function.

Sign Function :

Synonym: sign.

Signifier :

That part of a sign which stands for the signified, for example a word or a DNA

codon.

Synonym: token, sign vehicle.

Part-of: sign.

Token :

The physical entity or marker which manifests the signifer by standing for the

signified.

Synonym: signifier, sign vehicle.

Sign Vehicle :

Synonym: token, signifier.

Signified :

That part of a sign which is stood for by the signifier. Sometimes thought of as the

meaning of the signifier.

Synonym: object, referent, interpretant.

Part-of: sign.

Object :

Synonym: signified, referent, interpretant.

Referent :

Synonym: signified, object, interpretant.

Motivation :

The presence of some degree of necessity between the signified and siginifier of a

sign. Makes the sign proper, and complete motivation makes the sign lawful. For

example, a painting may resemble its subject, making it a proper sign.

Antonym: arbitrariness.

Arbitrariness :

The absence of any degree of necessity between the signified and siginifier of a

sign. Makes the sign symbolic. For example, in English we say "bachelor" to refer

to an unmarried man, but since we might just as well say "foobar", therefore

"bachelor" is a symbol.

Antonym: motivation.

Proper Sign :

A sign which has an intermediate degree of motivation. For example, a

photograph is a proper sign.

isa: sign.

Cases: icon, index.

Icon :

A proper sign where the motivation is due to some kind of physical resemblance

or similarity between the signified and siginifier. For example, a map is an icon of

its territory.

isa: proper sign.

Index :

A proper sign where the motivation is due to some kind of physical connection or

causal relation between the signified and siginifier. For example, smoke is an

index of fire.

isa: proper sign.

Symbol :

For CS Peirce, a sign where the sign function is a conventional rule or coding.

The operation of a symbol is dependent on a process of interpretation.

isa: sign.

Rule :

A functional regularity or stability which is conventional, and thus necessary

within the system which manifests it, but within a wider universe it is contingent,

or arbitrary. For example, if we wish to refer to an unmarried man in English, then

we must say "bachelor", even though "bachelor" is a symbol.

Synonym: code, semantic relation.

Antonym: law.

Semantic Relation :

Synonym: code, rule.

Code :

The establishment of a conventional rule-following relation in a symbol,

represented as a deterministic, functional relation between two sets of entities.

Synonym: semantic relation, rule.

Interpret :

To take something for something else in virtue of a coding.

Interpreter :

That entity, typically a human subject, which interprets the sign vehicle of a

symbol.

Interpretant :

For Peirce, that which followed semantically from the process of interpretation.

Synonym: signified, object, referent.

Law :

A regularity or stability which is necessary for all systems, and thus immutable as

a fact of nature. The necessity of the relation is called the sign's motivation.

Antonym: rule.

Semantic Closure :

Propounded by Pattee [ PaH82], the property of real semiotic systems like

organisms, wherein the interpreter is itself a referent of the semantic relation.

Semiotics for Beginners

Daniel Chandler

http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/

S4B/sem-gloss.html

Glossary of Key Terms

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Abduction: This is a term used by Peirce to refer to a

form of inference (alongside deduction and

induction) by which we treat a signifier as an

instance of a rule from a familiar code, and then

infer what it signifies by applying that rule.

Aberrant decoding: Eco's term referring to decoding

a text by means of a different code from that used to

encode it. See also: Codes, Decoding, Encoding and

decoding model of communication

Absent signifiers: Signifiers which are absent from a

text but which (by contrast) nevertheless influence

the meaning of a signifier actually used (which is

drawn from the same paradigm set). Two forms of

absence have specific labels in English: that which is

'conspicuous by its absence' and that which 'goes

without saying'. See also: Deconstruction, Paradigm,

Paradigmatic analysis, Signifier

Address, modes of: See Modes of address

Addresser and addressee: Jakobson used these terms

to refer to what, in transmission models of

communication, are called the 'sender' and the

'receiver' of a message. Other commentators have

used them to refer more specifically to constructions

of these two roles within the text, so that addresser

refers to an authorial persona, whilst addressee

refers to an 'ideal reader'. See also: Codes, Encoding

and decoding model of communication, Enunciation,

Functions of signs, Ideal reader, Transmission

models of communication

Aesthetic codes: Codes within the various expressive

arts (poetry, drama, painting, sculpture, music, etc.)

or expressive and poetic functions which are evoked

within any kind of text. These are codes which tend

to celebrate connotation and diversity of

interpretation in contrast to logical or scientific

codes which seek to suppress these values. See also:

Codes, Connotation, Poetic function, Realism,

aesthetic, Representational codes

Aesthetic realism: See Realism, aesthetic

Affective fallacy: The so-called 'affective fallacy'

(identified by literary theorists who regarded

meaning as residing within the text) involves relating

the meaning of a text to its readers' interpretations which these theorists saw as a form of relativism.

Few contemporary theorists regard this as a 'fallacy'

since most accord due importance to the reader's

purposes. To regard such purposes as irrelevant to

the meaning of a text is to fall victim to the 'literalist

fallacy' - a textual determinist stance. See also:

Decoding, Interpretative community, Literalism,

Meaning, Textual determinism

'Always-already given': See Priorism

Analogical signs: Analogical signs (such as paintings

in a gallery or gestures in face-to-face interaction)

are signs in a form in which they are perceived as

involving graded relationships on a continuum rather

than as discrete units (in contrast to digital signs).

Note, however, that digital technology can transform

analogical signs into digital reproductions which

may be perceptually indistinguishable from the

'originals'. See also: Digital signs

Analogue oppositions (antonyms): Pairs of

oppositional signifiers in a paradigm set representing

categories with comparative grading on the same

implicit dimension and which together define a

complete universe of discourse (relevant ontological

domain), e.g. good/bad where 'not good' is not

necessarily 'bad' and vice versa (Leymore). See also:

Binary oppositions, Converse oppositions

Analysis

Content: See Content analysis

Diachronic: See Diachronic analysis

Ideological: See Ideology

Paradigmatic: See Paradigmatic analysis

Poststructuralist: See Deconstruction

Structuralist: See Structuralism

Synchronic: See Synchronic analysis

Syntagmatic: See Syntagmatic analysis

Anchorage: Roland Barthes introduced the concept

of anchorage. Linguistic elements in a text (such as

a caption) can serve to 'anchor' (or constrain) the

preferred readings of an image (conversely the

illustrative use of an image can anchor an ambiguous