The Writer's Journey

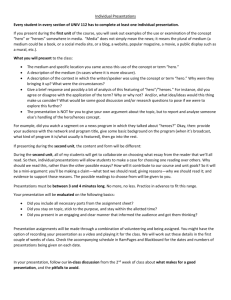

advertisement