CORD-PaperSubmission

advertisement

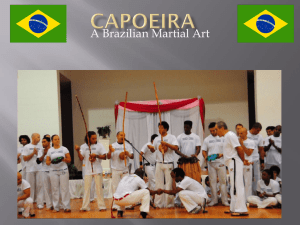

JOGO DE MANDINGA —GAME OF SORCERY— SECRET HISTORIES AND BODILY PRACTICE IN CAPOEIRA ANGOLA THE GAME-DANCE-FIGHT FROM BAHIA, BRAZIL Edward L. Brough Luna, BA Contents: A) Thesis Proposal (Includes Methodology) Approved Jan 2005 B) Selected samples from thesis-in-progress C) Bibliography A) T HES IS PR OPOS A L INT ROD UCT IO N Capoeira (kah-PWEH-dah) is a unique intertextual practice that brings together aspects of fighting, dancing, playing, music, and ritual. As one of the most visible signs of Brazil’s deep African heritage, capoeira is also a living cultural archive, encompassing over 500 years of history, mythology, ritual, slavery, prohibition, resistance, and survival. Since the beginning of its decriminalization in the 1930s, capoeira has also become the national sport of Brazil—a jogo bonito (“beautiful game”) second in popularity only to football soccer. In more recent decades, capoeira has even emerged as a global phenomenon—championed as a fighting form equivalent to other martial arts, a breathless show for tourists and theater audiences, and a source of inspiration for choreographers, break dancers, Hollywood action heroes, fitness gurus, and video game characters. Thus, a cultural form practiced primarily by marginalized, lower class Brazilians of African descent has managed to transcend the boundaries of race, culture, and country to offer the world a fascinating way to “play” through the difficulties and oppressions of everyday life. ST AT EMENT OF T HE PRO B LEM The practice of capoeira dates back at least to the 18th-century colonial era in Brazil, and perhaps hundreds of years earlier, to a practice of dance--fighting found in West Central Africa. Because it has been passed down from one practitioner to another, often under conditions of secrecy, few outsiders have had access to the secrets of capoeira until relatively recently (c. 1940). As a result, its history is riddled with complexities and contradictions that are only just beginning to be unraveled. Major problems haunt researchers of capoeira in this regard. First, there is the relative scarcity and unreliability of ‘‘hard” historical and ethnographic documentation about African and slave culture 3 throughout the period of the Atlantic slave trade.1 This is due in part to ethnocentrism on the part of European documentors,2 as well as the deliberate destruction of documentation by the Brazilian government in the 19th century.3 The difficulty extends to doing field research in today’s West Central Africa, where the historically important slave-trading areas now known as Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo have suffered vile civil wars and mass displacements of people in recent years. Furthermore, the notoriously heterogeneous and often secretive nature of present-day capoeira culture itself makes it difficult (not to mention politically explosive) to differentiate older traditions from newer innovations or stylistic hybrids. S IG N IF IC AN CE OF T HE PRO BLEM Despite these serious stumbling blocks, capoeira has attracted the interest of a wide range of researchers in various fields. The inherently multidisciplinary nature of the form—bringing together movement, music, ritual, and individual resourcefulness into one practice—has already led to examinations of the form informed by cultural anthropology, athletic pedagogy, Latin American and African history, performance studies, martial arts, and Brazilian ethnomusicology, among others. 1 Chike Aniakor is more optimistic about the number of materials available: “. . . there are indeed materials which can aid early dance studies in spite of their severe limitations in terms of the tendency for cultural-prejudicial interpretations. . . “ Chike Aniakor, “Early Written Sources on African Dances from the Seventeenth Century to 1915,” in The Spirit’s Dance in Africa: Evolution, Transformation and Continuity in Sub-Sahara. Esther A Dagan, ed. Montreal: Galerie Amrad African Arts Publications, 1997. p. 56. 2 Aniakor (ibid.) refers to Adam Jones and Beatrix Heintze’s assertion that “. . . few academic historians of Africa—whether African or non-African—would seriously deny that our knowledge of sub-Saharan Africa (taken as a whole) between the fifteenth and ninetheenth centuries (the period for which oral tradition is of most relevance) must and always will rest principally (though by no means exclusively) on European sources.” They also add that “in many cases the quantitiy of the materials is offset by its unreliability.” p. 56. 3 In 1890–91, Ruy Barboso, then Finance Minister of Brazil, ordered the burning of all government documentation about slavery. See Edison Carneiro, Antologia do negro brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Edições de Ouro, 1967. p. 89. However, in more recent years there has been some doubt as to how much of the material was actually destroyed, and some scholars (such as Líbano Soares) have found archives outside Brasil. Carlos Eugenio Líbano Soares, personal communication, Aug 2004. 4 For scholars of dance or movement studies, however, the most important source of information about capoeira is the movement itself. Yet this is precisely the area which has been almost totally neglected by current scholarship. Because of this I believe it is essential, as well as timely, to undertake such a study. While such work must reasonably focus on the contemporary practice of capoeira (which is arguably a “reenactment” of an earlier practice) I believe that an in-depth examination of capoeira movements from the point of view of “bodily history” may offer us important glimpses into the longforgotten past and at the same time speak to the current situation of Afro-Brazilians themselves. This research may also allow scholars to gain a deeper understanding about how an African (or Africanist) movement form would have been utilized to comment on and/or resist the institution of slavery. And because capoeira shares a history of bodily oppression and resistance with other African diasporic forms (including Afro-Cuban dance, jazz dance in the U.S., and other Brazilian forms such as the samba), it may also offer new perspectives on the experiences of the African diaspora in the Americas in general. Studying capoeira may even offer a new way to consider the body itself—as a rich source of historical, pedagogical, dynamic, kinesthetic, and cognitive information. With its inherent deceptions, surprises, layers of meaning, and physical demands on the body, capoeira may come to be appreciated as a well rounded approach to health, survival, and long life (as evidenced by the number of capoeira mestres—masters—practicing well into their 70s and 80s).4 Such investigations are also likely to shed light on the vitality of the practice of capoeira outside of Brazil: in the academies and universities of North America, Europe, and Asia, where capoeira has flourished, and where its future may lie. PURPO SE OF T HE S T UDY 4 For example, at this writing (Jan 2005), João Pequeno is about 88 years old, João Grande is about 72, Boca Rica is about 67. Mestre Curió, himself about 70 years old, claims his father still plays capoeira in his 100s (!). 5 This thesis is intended as a preliminary, and evolving effort to a) bring together some of the “hard” facts of historical research on capoeira and related forms, while placing a certain “faith” in the oral—and bodily—history of capoeira as learned through my own research, training, and teaching in the form. This thesis may also serve as preliminary attempt to b) document and analyze the teachings and movements of capoeira for future researchers, as a complement to traditional instruction by a living capoeira mestre, not a replacement. Additionally, it is hoped that by speaking from within the practice, capoeira may be seen as a tradition worthy of preservation, and of continuing relevance. ASSUMPT ION S AN D L IM I T AT ION S This work will focus almost exclusively on the traditional form of capoeira, known as capoeira angola, as it has been transmitted to me by my teacher, Mestre Caboquinho. Mestre Caboquinho (b. José Dantas, 1964) is a native of Bahia, Brazil, who currently lives in Detroit, Michigan. He is one of the foremost proponents of traditional capoeira angola outside of Bahia. In accordance with his own teaching philosophy, I am approaching capoeira angola as a tradition in its own terms: not a “modernized” version of a traditional practice, but a direct descendant and living representation of a traditional practice. The most obvious limitation of this approach is my own status as a relative beginner in the form. In capoeira angola, the giving of ranks and titles is often a long and complicated process that must ideally be presided over by a community of mestres.5 So, in the writing of this thesis, I have taken on an 5 In the days before capoeira academies (c. 1920), the title of mestre was given informally and liberally, not only to capoeira practitioners but as a respectful title (similar to the informal use of “Don” and “Doña” in Spanish). However, while the title of mestre is still used as an honorary, informal one, and continues to be bestowed upon older capoeira practitioners, it is incredibly difficult to gain the title “officially.” A number of prominent mestres of capoeira angola, in fact, were never given their title by any recognized body. This remains a source of quiet controvery in the world of capoeira angola, which prides itself on being different from more contemporary styles of capoeira, in which the position of mestre has often been severely devalued. 6 unusually high level of responsibility which, in some eyes, may be seen as presumptuous and premature.6 My awareness of this dilemma has necessitated the framing of this thesis as a “preliminary and evolving” effort. At the same time, Mestre Caboquinho believes that under his guidance, he has prepared me to work well “within the tradition” of capoeira angola. As such, he has acknowledged the legitimacy of my research, as well as my leadership of a satellite group of his organization, the Tribo Afro-Bahiana de Capoeira Angola Tradicional (T.A.B.C.A.T.), and my continued teaching of an introductory capoeira course at The Ohio State University Department of Dance. As a scholarly pursuit, however, it may be asked whether it is even possible to claim an “authentic” tradition of capoeira. Indeed, among most capoeira practitioners themselves (and a majority of scholars), it is generally accepted that many of the traditions of capoeira have been lost, rediscovered, and reinvented throughout the years, especially since the 1960s. In other words, capoeira has supposedly “adapted” to its surroundings, and “evolved” through time, as any movement style passed informally from individual to individual is likely to do.7 Yet, while it may seem reasonable to acknowledge that the capoeira performed in today’s academies is somewhat different from the street rodas of Rio de Janeiro, Recife, and Bahia in the 1860s, 6 I estimate that the average time it takes to become a mestre in capoeira angola is approximately 20 years. The intermediate titles such as trenel (trainer) and contra-mestre (half or assistant mestre) may take approximately 3–5 years and 8–10 years to obtain, respectively. As I have only been training for approximately 4 years (but only 2 1/2 with my mestre) I might qualify as an “intermediate beginner.” 7 Bira Almeida (Mestre Acordeon) is one of the more prominent advocates of what might be called the “adaptive” view of capoeira. An excellent online essay entitled “Capoeira: An Introductory History” is permeated by this idea, summed up unequivocally by the assertion that “capoeira has undergone many changes throughout the times.” When I posed this to Mestre Caboquinho, he dismissed the notion, saying that “capoieira doesn’t change.” In his view, the core principles of capoeira are in and of themselves adaptable enough to survive in different contexts without changing. It is worth noting here that, in his own academy, Acordon has gone against a number of practices taught by his own mestre (Mestre Bimba), including the use of belt rankings. See Bira Almeida, “Capoeira: an Introductory History,” <http://www.capoeira.bz/articles/history.html>, 1996. 7 or the earlier dance-fights of Africa,8 it is also true that the notion of a continuity of “bodily history” has remained largely unaddressed. In other words, instead of limiting my attention to what has changed in the practice of capoeira, this thesis will also try to focus on what has probably stayed the same. As a matter of “faith,” then, I will often write from the view that, despite some changes on the surface, the core principles of capoeira have survived relatively intact. (With regard to the problematic use of the word “faith” in a work of scholarship, I shall simply acknowledge, for now, that it is my faith in the traditions of capoeira angola that has allowed me to access some of its deeper truths, and to gain the [always provisional] trust of my own mestre, without whom this work would be irrevocably diminished.) REV IEW OF R ELAT ED L I T ERAT URE As already noted, capoeira has in recent years attracted students and scholars from a variety of academic disciplines. While this has led to a “mini-boom” of articles and books on the subject, the number of scholarly writings on capoeira (especially in English) has remained relatively small. This may be attributed in part to the fact that the sources of academic and historical knowledge about capoeira are also relatively scarce. As stated earlier, research into the historical record of capoeira is riddled with difficulties. Moreover, before the 1930s, capoeira was considered a criminal activity unworthy of attention or serious research (a stigma that remains prevalent even today).9 Because of this, older scholars of Brazilian and capoeira history—notably, early 20th century writers such as Manuel Querino, Edison Carneiro, and Arthur Ramos—have generally relied on the same set of primary materials: consisting of a few tourist accounts, romantic pulp novels, police and military records, and the rare ethnographic morsel 8 Indeed, M. Acordeon has made the reasonable (Western) assertion that we cannot “reconstruct” the capoeira of even 100 years ago. See Capoeiragem na Bahia, Dir. José Umberto. IRDEB/TVE, Bahia, Brazil, 2000. 9 Nearly all of the Brazilian Dictionaries I have consulted have identified “capoeira” with criminality, even into the 1970s. Even today, middle-class Brazilians look at capoeira with disdain. A member of our group who revealed his devotion to capoeira to a 20-something ladyfriend in Bahia was immediately chastized for “not being serious.” 8 from the 1800s. They often turned towards ethnographic research on their own, investigating the capoeira of their own time and making forays into the oral histoy of Afro-Brazilian culture. These descriptions provided intriguing glimpses into Bahian capoeira at the turn of the 20th century. However, because they were not practitioners, their accounts are of limited value today. Others, such as the Rio de Janeiro author of a 1907 guide to capoeira training, even published anonymously, so as to avoid legal attention during the long prohibition of the form from 1890–c. 1940. With the exception of a few other “manuals” of capoeira practice, very little additional scholarship was made available until the publication of Waldeloir Rego’s Capoeira Angola: ensaio sócio-etnográfico (1968), a 400-page volume collecting a wide range of materials from Bahia, primarily songs and etymologies. Even so, almost twenty years would elapse before anyone else attempted to follow this work up more thoroughly. While a handful of historians such as Muniz Sodré, Robert Farris Thompson, and Luís César de Souza Tavares published essays and related tracts in the 1980s, most readily available writings about capoeira published after 1968 have been by practitioners with a mixed level of academic experience. Students of the famed Mestre Bimba, father of the modernized form of capoeira regional, have dominated the discussion thus far. Works by these students, including Jair Moura (1980), Mestre Itapoan (1992), Angelo Augusto Decânio Filho (various), and Mestre Acordeon (1986), along with other notable books by Nestor Capoeira (1995) and Mestre Bola Sete (1989), have mostly documented personal experiences, the teachings of their own mestres, or the recollections of other old mestres. Since 1990s, however, another generation of scholars—including more from the U.S. (and even some of the earlier writers such as Nestor Capoeira, who has since gained an academic title)—have taken on the more ambitious task of uncovering the history of capoeira through more rigorous archival, historical, phenomenological, anthropological, socio-political, and even theological research. Authors such as Carlos Eugênio Líbano Soares (1994, 2002), Antônio Liberac Cardoso Simões Pires (2002), Greg Downey (1998, 2005), Letícia Vidor de Sousa Reis (1997), J. Lowell Lewis (1992), T. J. Desch-Obi 9 (2000, 2004), Augusto Januário Passos da Silva (2003), and Floyd Merrell (2005) have greatly expanded the scope and depth of the literature of capoeira. Of these, Desch-Obi and Soares are the most thorough. In his Ph.D. dissertation (2000) Desch-Obi provides a very convincing argument about the transmission of African foot-fighting techniques to Brazil, while Soares (in A Negregada Instituição, 1994, and A capoeira escrava, 2002) has pored through police and military records on three continents to provide a very detailed record of capoeira in 19th-century Rio de Janeiro, encompassing nearly 1000 pages thus far. Soares’ recent move to Bahia suggests he may move onto the history of Bahian capoeira next. Yet even such towering works of scholarship have done little to describe, let alone analyze, the movements of capoeira themselves. This astonishing fact calls attention to the scarcity of research into what is seemingly the most important aspect of capoeira: the movement. Aside from the capoeira “manuals” of Nestor Capoeira and others (which are of limited use for actually learning the form) the only authors who have thus far attempted any kind of preliminary analysis of capoeira movements have been J. Lowell Lewis (1992), who interspersed his highly detailed semiotic analysis with terms culled from Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) and Dance Dynamics; and Greg Downey (1998, 2005), who has examined capoeira movements from a phenomenological viewpoint. Still, the movements of the form have yet to be thoroughly investigated as a primary source of data in a work of serious academic scholarship. This thesis will attempt to partially address an unfortunate lack. 10 MET HODOLOG Y DES IGN OF T HE ST UDY This thesis will be structured in two sections. In Section One, I will focus on historical issues, such as an outline of Brazil’s early history, and an examination of various African, rural, urban, and recent influences on the form. I shall attempt to incorporate historical, contemporary, and oral sources in this effort. Section Two will focus on the movements of capoeira angola using observational and kinesthetic techniques based primarily on the framework of Laban Movement Analysis. This section will focus on Effort Qualities, Body/Shape, Space Design, and Dance Dynamics, and will also include an as-yetundetermined number of examples of capoeira movements and sequences written in Labanotation, designed to provide future scholars with a glance into the form’s overall characteristics, strategies, and performance style. These examples may also serve as the beginning of a more thorough documentation of the form. An appendix on the music and instruments of capoeira angola, with some thoughts about the dialogue between music and movement, will also be included. PROCEDURES In exploring the central themes of this thesis, I have come about my hypotheses by combining deductive and inductive research procedures. For example, at times, I have approached capoeira with a specific idea about its function throughout history (i.e., “capoeira as a martial art”), and have pursued material that would support this idea. At other times, I have tried to examine capoeira from its own discourse, allowing its philosophies and movements to inform my analysis. Much of this discourse has been ascertained from my own conversations with mestres and fellow students, as well as the experience of taking class and performing capoeira in a wide variety of situations myself. 11 In reconstructing a meaningful narrative about the history of capoeira, I have tried a similar approach: combining (often contradictory) written, photographic, oral, anecdotal, sartorial, pedagogical, and bodily sources into a cohesive whole. In this, I have at times allowed myself to engage in “speculative history,” in order to understand otherwise inaccessible psychological aspects of the form. While this procedure cannot in and of itself provide verifiable data in the traditional research sense, I believe it has been a valuable tool, perhaps similar to the exobiologist’s use of imagination to describe possible (but unprovable) conditions for the evolution of alien life forms. My position as a scholar, practitioner, and even teacher of the form has also offered me an invaluable, insider’s point of view to this form, which arguably offsets any potential dangers of the “speculative” approach. As a practitioner who has fully given himself over to the traditions, logic, and philosophy of capoeira angola, I have been given unprecedented access to the secrets of the form. In ethnographic terms, this would be described as a reflexive ethnography, permeated by my own personal findings and experiences. SOURCES OF DATA For the historical section of the thesis, I have drawn primarily from the major texts on capoeira, as well as a few lesser known sources (see Bibliography). I have also relied on secondary sources at The Ohio State University to provide a more general context about the African experience in Brazil. Specific research was also conducted at the NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Academic research in Bahia was limited to the Biblioteca Central dos Barris in Bahia, due to a strike of university library workers. I have also relied heavily on a number of internet sites, some of which contain quite extensive scholarly information, often including: translations of primary texts, transcriptions of and/or essays on historical texts, collections of personal research, and critiques of current scholarship. Capoeira internet forums have also been a useful way of crosschecking certain information; they also offer a window into current, worldwide conversations about capoeira, from beginners trying to clear up misconceptions, to 12 longtime practitioners arguing about the fundamental issues of capoeira history. While use of the internet remains a slippery affair, I have tried to corroborate most information obtained there with other sources. My most important resource (for movement, as well as oral history) has been my mestre and teacher, Mestre Caboquinho. As of this writing (January, 2005), I have studied with Mestre Caboquinho for two and a half years, and also joined his organization for a five week stay in Salvador, Bahia (August, 2004). In Bahia, I had the opportunity to train, perform, and research capoeira with members of T.A.B.C.A.T. and on my own. Since 2001, I have also participated and observed at the New York City academy of Mestre João Grande, a Bahian now in his 70s, who is considered the foremost representative of the older lineage of capoeira angola in the U.S. The other source of data is my own teaching of the form at The Ohio State University, which has involved several quarters worth of 10-week classes through the Department of Dance, as well as nearly four years of leading a capoeira group (now an official T.A.B.C.A.T. satellite) in Columbus. Through these experiences, I have had the unique opportunity of transmitting capoeira to new students in the midst of learning it myself. This has led to some misrepresentations, miscommunications, and confusions (especially with my own mestre), but the process of sorting through these problems has also yielded a number of interesting discoveries (including new pedagogical tools, and better understanding my role as “mestre” or leader of a capoeira group) as well as questions (such as the relevancy of a “traditional” but ambiguous form to a more “modern” and literal-minded North American audience). DATA COLLECTION METHODS Academic materials—books, articles, texts, etc.—as well as internet materials have already largely been compiled. These may be further honed and sorted as the thesis progresses. As a number of materials are written in Portuguese (at which I am an acceptable reader), some translations for the benefit of the reader may therefore be required. 13 My classroom experiences with Mestre Caboquinho (and others) have been compiled by means of extensive class notes and occasional photographs and recordings. My teaching experiences, discoveries, and questions have been collected by means of teaching notes, personal anecdotes, student assignments, questionnaires, take-home examinations. I may also conduct a number of interviews with current and former students to clarify any questions. DESCRIPTION OF DATA-GATHERING INSTRUMENTS Most of the written materials have been collected by means of standard research methods such as extensive library and web searches. Class and other “live” cultural materials (primarily in Bahia) have been gathered by means of a Mini-disc recorder, videotape, and digital still photography. However, because transmission of the form is so dependent on physical demonstration (and because most mestres are uncomfortable with the use of recording devices, for reasons which I hope to adequately convey), my own “muscle memory” (aided by written notes and recollections) will often serve as my primary “instrument.” In using these reflexive ethnographic methods of data gathering, from my own personal experience, and the memory of struggling and sweating with the movements and philosophies of capoeira angola, it is hoped that this thesis may be an appropriate addition to the nascent field of “capoeira studies.” 14 B) SELECT ED SAMP LES FROM T HES IS -I N PRO GRESS From: MODERN IZAT ION: T HE 2 0T H CENT URY . . . . Even as capoeira was beginning to be documented as a criminal phenomenon in such coastal cities as Rio de Janeiro, Salvador (Bahia), and Recife throughout the 19th century, very little was recorded about the form’s physical appearance. A recent 600-page work on capoeira culture in Rio from 1810–1850 (Soares, 2002), for example, effectively contains no description of the form’s appearance. A further 40 years of harsh repression and prohibition (c. 1890–1940) by the Brazilian Republic ensured that the movements of capoeira remained mostly secret. In Rio, it is believed that capoeira was all but abolished, surviving only in the seedy underground culture of the favela shantytowns,10 and as a brutal martial art taught in military academies, with little ritual or musical context. In Recife, where capoeira was associated with colorful street processions, it disappeared into another dance, called the passo. It was only in the old colonial capital of Salvador, Bahia, where capoeira managed to live on as a as a musical game-dance-fight symbolizing the subterfuge and resistance necessary for everyday survival. It was in Bahia that capoeira may have taken on the more deliberate appearance of a dance, hidden through the use of drums, tambourines, and an ancient African bow instrument called the berimbau. Throughout the prohibition, many streetwise mestres (masters) of capoeira remained active in Bahia. Among these were two remarkable men who fought for the recognition of the form. It is largely because of their efforts that the movements and mythologies of capoeira were finally revealed to the world. Mestre Bimba (c. 1899–1974), originally a much-feared mestre of traditional capoeira, decided to ‘clean up’ what he saw as a dying and ineffective fighting form. By the early 30s, he had created his own, streamlined version of capoeira, initially called luta regional baiana (or ‘regional fight of Bahia’) to avoid the illegal word, capoeira. Under the guidance and influence of several of his students (including the doctor and ju-jitsu enthusiast Cisnando Lima), he discarded many of the ritualized movements of 10 The recent Brazilian film Madame Satã (Dir. Karim Aïnouz, 2002) documents the life of João Francisco dos Santos, one of the notorious malandros (rogues) of Rio’s Lapa district. In addition to being a drag queen, Santos was also said to have been a powerful capoeira player. 15 capoeira, and brought capoeira indoors; introducing formalized sequences of movements, acrobatic throws, uniforms, and specific ‘rites of passage’ for his students (such as baptisms and graduations). Bimba’s efforts served to bring an unpredictable, unsavory, street-fighting form in line with a new kind of Brazilian nationalism that saw the country as a seamless mixture of Amerindian, Portuguese, and African cultures. This codification also allowed capoeira to become more widely accessible and acceptable to lighter-skinned, middle class Brazilians, which played an important role in its eventual decriminalization. Under Bimba, capoeira regional also became Brazil’s de facto “national sport,” as well as a devastating fighting form that could equal (and often defeat) other martial arts in challenge matches. However, this modernization of capoeira also resulted in a number of problems, often stemming from a misunderstanding about Bimba’s intentions in creating his luta baiana, or capoeira regional. Mestre Bimba himself does not appear to have tried to “replace” the traditional capoeira of his own upbringing, but rather to create a streamlined version of the form that was a completely new system—a stylization that suited his personality, and that, coincidentally, suited the needs of a new national identity. It is also interesting to note that Mestre Bimba was the only traditional capoeira practitioner to have split from the tradition to make his own style of capoeira; a fact that is readily apparent when listing the dozens of traditional mestres from Bimba’s heyday, who are completely unknown today. By the 1960s, new groups in other parts of Brazil (most notably, the Grupo Senzala from Rio de Janeiro) followed in Bimba’s footsteps, by taking the basic, streamlined template of regional and adding their own stylizations. Most introduced new training methods, movements, belt rankings, and techniques from other martial arts or bodily practices (such as tae kwan do, gymnastics, wrestling, and even yoga); while others claimed to be recuperating remnants of Rio’s own capoeira carioca. This “contemporary” style of capoeira, only a secondary derivative of Mestre Bimba’s regional, has become the primary force in the modernization, globalization, and homogenization of the form. It is also the most popular, visible form of capoeira, practiced throughout North and South America, Europe, and Asia. While emphasizing competition, fast games, fighting techniques, and powerful acrobatics, the 16 popularity of ‘contemporary’ capoeira has arguably come at the expense of the African and Bahian roots of capoeira, where, by contrast, capoeira is still understood as a playful (and somewhat secretive) pastime. Throughout the development, rise, and dominance of capoeira regional and its competitive derivations, traditional capoeira continued to be performed as an informal, ironic, street game that was deeply connected to Afro-Brazilian culture. In the 1940s, it became known as capoeira angola, to distinguish it from the growing style of regional, as well as to acknowledge the possible Bantu origins of the practice. Among dozens of mestres of capoeira angola, the gentle and philosophical Mestre Pastinha (1889– 1981) became the most widely known. His academy, established in the 1940s, was an important focal point for capoeira angola, and Bahian culture in general (author Jorge Amado was a frequent visitor). It is largely thanks to the elder Pastinha, and the angoleiros who passed through his doors, that many of the traditions of capoeira angola were compiled, preserved, and passed on. Still, by the 1970s capoeira angola was nearly lost, thanks to the continuing growth of competitive capoeira, as well as the informal teaching methods of many of the old mestres themselves—who taught only a handful of students at a time, often without structured lessons. A revival of capoeira angola in the 1980s, mostly by ex-students of Pastinha, borrowed heavily from the “academic discourse” of regional, by bringing classes indoors, formalizing lessons, and adding a renewed emphasis on African and AfroBrazilian consciousness. Through the process of capoeira angola’s own “contemporization,” and its reactionary opposition to capoeira regional, a largely intuitive, informal art has itself risked standardization, politicization, and loss of tradition. Because of this, a number of lesser known mestres from other lineages have begun to emerge. Teachers (such as the author’s own Mestre Caboquinho) have more or less resisted such modernizations, trusting that the traditions themselves may continue to sustain capoeira angola in the modern world. 17 From summary of Movement Analysis section: . . . . This analysis will focus on Effort Qualities, but will also pay attention to issues of Body/Shape, Space Design, and Dance Dynamics. For example, in traditional capoeira angola training, attacks emphasize the Effort Factors of Time/Weight, with an affinity for the qualities of Sustained/Light. This serves to build trust between partners working to learn new sequences of movements. However, in the actual performance of the form, this tendency is interrupted by frequent use of Quick/Strong for surprise attacks. Additionally, because the form is not intended to harm the opponent, players must also have immediate access to Bound/Flow, to avoid impacts. These tendencies, put together, are suggestive of the feinting movements seen all over the African diaspora in the Americas, where the body is repeatedly “opened” and “closed” (i.e. the grandstanding gestures of hip-hop). Capoeira angola also uses terms suggestive of Dance Dynamics, The form is often ironically brincadeira (“joking around”) or vadiação (“doing nothing in particular”), indicating a relaxed but highly alert attitude appropriate to a street-oriented form. This attitude is demonstrated dynamically in a series of casual feints called mandinga (or ‘sorcery’), used to distract the opponent and disguise one’s true intentions. Likewise, a player adept at malícia (“treachery” or “double dealing”)11 may collaborate closely with the opponent, only to interrupt the game with a surprise attack. 11 After Lowell Lewis (1992), it should be recalled that malícia should not be translated literally as “malice,” but rather as a much milder, ambiguous term akin to “cunning.” 18 C) B IB L IOGR APH Y SELECT ED PR IMAR Y SOU RCES Abreu, Frede. O Barração do mestre Waldemar. Salvador, Bahia: Organização Zarabatana, 2003. Almeida, Bira. Capoeira: A Brazilian Art Form: History, Philosophy, and Practice. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1986. Browning, Barbara. “Headspin.” Samba: Resistance in Motion. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1995. Capoeira da Bahia. Angelo Augusto Decânio Filho, Ed. <http://planeta.terra.com.br/esporte/capoeiradabahia/>. “A Capoeira de Sinhozinho.” Dec. 2004 <http://rohermanny.tripod.com/>. Capoeira do Brasil. Brazil: <http://www.capoeiradobrasil.com.br/>. Capoeira Ginga Nâgo. France: <http://www.ginganago.com/>. Capoeira, Nestor. Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game. Berkeley, California: Books, 2002. ----------. The Little Capoeira Book. Revised ed. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2003. Cascudo, Luís da Câmara. Dicionário do Folclore Brasileiro. 5th ed. revised. São Paulo: Edições Melhoramentos, 1979. Debret, Jean Baptiste. Viagem Pitoresca e Histórica ao Brasil. São Paulo: Biblioteca Histórica Brasileira—MEC, 1975. Desch-Obi, Thomas J. “Engolo: Combat Traditions in African and African Diaspora History.” Ph. D. Thesis UCLA, 2000. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2001. Downey, Greg. “Incorporating Capoeira: Phenomenology of a Movement Discpline.” Doctoral dissertation, U of Chicago, 1998. 19 North Atlantic Freyer, Peter. Rhythms of Resistance: African Musical heritage in Brazil. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 2000. Karasch, Mary C. Slave life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP, 1987. Kazadi wa Mukuna. Contribuição bantu na música popular brasileira: perspectivas etnomusicológicas. São Paulo: Global Editora, 1978. Kubik, Gerhard. Angolan traits in Black music, games and dances of Brazil: a study of African cultural extensions overseas. Lisboa: Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar, 1979. Lewis, J. Lowell. Ring of Liberation: Deceptive Discourse in Brazilian Capoeira. Chicago: The U of Chicago P, 1992. Mattoso, Kátia M. de Queirós. To be a slave in Brazil, 1550-1888. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer; foreword by Stuart Schwartz. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers UP, 1987. Mestre Bola Sete. A Capoeira Angola na Bahia. 4th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Pallas, 2003. Pires, Antônio Liberac Cardoso Simões. Bimba, Pastinha e Besouro de Mangangá: Três personagens da capoeira baiana. Tocantins: Fundação U de Tocantins, 2002. Powe, Edward L. Danced Martial Arts of the Americas. Madison, WI: Dan Aiki Publications, 2002. Rego, Waldeloir. Capoeira Angola: Ensaio Sócio-Etnográfico. Salvador, Bahia: Editora Itapuã, 1968. Reis, Letícia Vidor de Sousa. O mundo de pernas para o ar, a capoeira no Brasil. São Paulo: Ed. Publisher Brasil, 1997. Rugendas, João Maurício. Viagem Pitoresca através do Brasil. São Paulo: Livraria Martins Editora S.A., 1954. Silva, Augusto Januário Passos da. A Capouêra e a Arte da Capueragem: Ensaio Socio-etimológico. Salvador, BA: Fundação Gregório de Mattos, 2003. 20 Soares, Carlos Eugênio Líbano. A capoeira escrava e outras tradições rebeldes no Rio de Janeiro (1808–1850). Campinas, São Paulo: Editora Unicamp, 2002. ----------. A negregada instituição: os capoeiras na Corte Imperial, 1850–1890. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Access Editora, 1999. Vieira, Luiz Renato. O jogo da capoeira: corpo e cultura popular no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Sprint, 1998. SELECTED SECONDARY SOURCES Carneiro, Edison. Candombles Da Bahia, 2a. ed., revista e ampliada, com 14 desenhos de Carybe. Rio de Janeiro: Editorial Andes, 1964. Johnson, Paul Christopher. Secrets, Gossip, and Gods: the Transformation of Brazilian Candomblé. New York: Oxford UP, 2002. Nishida, Mieko. Slavery and Identity Ethnicity, Gender, and Race in Salvador, Brazil, 1808–1888. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2003. Mendes, Luiz António de Oliveira, Memória a Respeito dos Escravos e Tráfico da Escravatura entre a Costa d’África e o Brazil. Memoria Apresentada à Real Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, 1793, 2 ed., Porto: Publicações Escorpião, 1977. Ramos, Arthur. O negro na civilização brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria-Editôra da Casa do Estudante do Brasil, 1971. Reis, João José. Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1993. Rodrigues, Nina. Os Africanos no brasil. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. Sweet, James H. Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the Portuguese World, 1441–1770. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2003. 21 V ID EO ‘Capoeiragem’ in Bahia. VHS video. Dir. José Umberto. IRDEB/TVE, Bahia, Brazil, 2000. Capoeira Angola do Mundo. DVD. Capoeira Angola Center of Mestre João Grande, NYC, 2003. O Pulo do Gato. DVD. Feat. Mestre João Grande & Mestre João Pequeno. Capoeira Angola Center of Mestre João Grande, NYC, 2002. Pastinha! Uma Vida pela Capoeira. VHS video. Dir. Antonio Carlos Muricy. 1999. 22