Here's - MathBench

advertisement

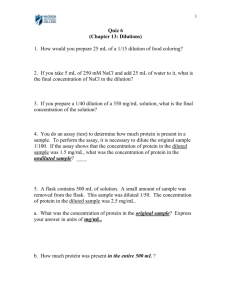

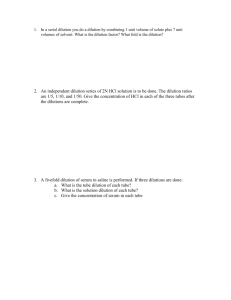

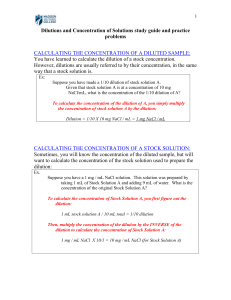

www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 1 Population Dynamics: Serial Dilution URL: http://mathbench.umd.edu/modules/cell-processes_serial-dil/page01.htm Note: All printer-friendly versions of the modules use an amazing new interactive technique called “cover up the answers”. You know what to do… Recap the story Remember Frank? Frank who had roommate from Sweden? Frank, who accidentally managed to host a few super-virulent meningicocci -- the kind that are common in Sweden, but rare here? Frank, who is now sitting in the doctor's office, looking a bit like one of those angsty teenage vampires, with a jacket over his head to protect his eyes, a rash all over his body, and a neck as stiff as a board? Yeah, that Frank. Well anyway, when the young medical intern (you!) cultured some meningicocci, you found that they double just about every half hour. If Frank's body is as nice a place for meningicocci as the petri dish is, you decided Frank should be dead by now. Poor Frank... Ah, but luckily Frank's body is not quite as cushy as a petri dish, due to his killer immune system, and also the inconvenient fact (if you're a meningicoccus, that is) that Frank's blood keeps its iron safely tucked away inside red blood cells. Curses, foiled again! Nevertheless, even though Frank's not dead, he's not doing so well either. And what we need to do is to find out just how badly off he really is. We need to measure that infection. But how? Count 'em all? Let's get one thing out of the way, right away. Given that Frank has been sick for a half day or so, there could be millions, even billions, of meningicocci in his blood. Do we want to count every single one? Yes, I love to count: Hmm, try again. No, because that would mean filtering all of his blood: That's true, and there's another reason as well. No, because it takes a really long time to count a billion: Yes, this is a really good reason not to count every meningicoccus. So, having established that we can’t count’em all, what else can we do? We could sample a little of his blood: Yes, we could. We should. We will. We could give up: Hmm, I don't think that's the way into med school... www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 2 Direct count So, Frank's got about 5 liters of blood, and he probably won't miss a few mLs all that much. Let's say we took that 10 mL, centrifuged out the gigantic stuff like red blood cells, put the rest on a slide under a microscope, and counted every thing that looked like a meningicoccus. That's certainly one way of quantifying the population. We'll call it ... Direct Count. Pretty easy, conceptually speaking, although it takes a bit of time to do the centrifuging and to make the slide, and even more time to actually count. But, that's what underpaid lab interns are for, right? OK, so you've counted using a Petroff Hausser chamber under the light microscope and found that you have 326 meningicocci in 10mL of blood. What does that mean? A less experienced lab intern might run off to tell the doctor that Frank has a total population of 326 meningicocci living in him. Not you, however, because you remember that you only sampled 10 mLs of Frank's blood. What you need to know is what fraction of Frank's blood you sampled: 10mL/5000mL = 1/500th So, in Frank as a whole, you would expect to find about 500 times as much as you did in your sample. 500 * 326 = 163,000 meningicocci This scaling up method (sometimes called multiplying by the inverse) is absoluately critical for successfully calculating the actual population from a sample. The online version of this module contains an interactive applet which allows you to practice scaling up. To find this applet go to: http://mathbench.umd.edu/modules/cellprocesses_serial-dil/page03.htm Light scatter (using spec) Direct count is a straightforward way to figure out how many meningicocci Frank is harboring, but it is a bit labor intensive. Wouldn't it be nice to get a machine to do the counting for us? One way we can do this is to use a photospectometer. A spec doesn't exactly count the cocci, but it does measure how much they interfere with a light beam, and based on that, we can use a calibration to decide how many cocci we've got. Then we can do the scaling up trick to get the total population size. www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 3 This is a great method if you already have a calibration curve -- perhaps you work in a lab that has been studying this critter for years... Otherwise, you may need to spend a couple of days doing the calibration (growing the cultures, taking the spec readings, comparing them to counts under the microscope... that sort of thing). Here's an example of a calibration curve: For example, if you prepared a sample and got a spec reading of 0.5, you would find 0.5 on the x-axis and read the bacterial count off the y-axis -- about 26 million look at the graph! How about a spec reading of 0.9? (Be careful with the log scale for bacteria!!) about 75 million If your sample had about 12 million bacteria, what OD reading would you expect? OD = 0.2 The dilemma of the dead cell So far we have one hard way (Direct Count) and one easy way (Photospec) to quantify Frank's meningicoccal load. But both ways share a big problem ... the dilemma of the dead cell. If you were counting, say, cats ... this wouldn't be a problem. A dead cat and a live cat are generally not easily confused. If in doubt, you could poke the cat, and you would know for sure. However, bacterial cells are much less lively than cats. Yes, there is plenty of stuff going on inside, but in general you're not going to see that from the outside. Under a microscope, cells that are alive and cells that are dead look a lot alike. And to a spec, live and dead cells look exactly alike. www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 4 Based on the dilemma of the dead cell, which would you predict? Direct count and photospec will...? Overestimate the population: yes, these methods overestimate, because the dead cells get counted as if they are alive Underestimate the population: the population won't be underestimated, because too many cells get counted, not too few. Get the population just right: the population will not be accurately estimated, both methods count too many cells. If we care about getting the number of live cells right, we need a better way… Viable plate count So we can't poke a cell to see if it's alive -- how else can we make the call? What do live cells do that dead cells don't? Well, one big thing is, live cells grow and reproduce. And they do it fairly quickly (remember, every half hour or so in the case of meningicocci). So if we were to take a batch of cells and wait a day or so, we would soon know if they were alive or not. Let's refine this idea a little, by following... A day in the life of a microbe Out in the real world (like in your nose, throat, or bloodstream), meningicocci are limited by temperature and nutrients. In the lab, we're going to put the meningicocci on a media, which will do two things: 1. take away limiting factors, and 2. fix each individual cell in one place, so it doesn't get moved around. So, let’s watch a single meningicoccus cell, conveniently named Minnie, sitting in the middle of a batch of media. The media has every creature comfort that Minnie could want, and she pulls in sugar as fast as she can. Soon she’s grown out of her membrane and she splits in half, creating little Minnies 2 and 3. These two also pull in sugar as fast as they can, and a half hour later, they too start to feel ready to split, so they do. Minnies 4, 5, 6 and 7 keep going. time: 0 min time: 50 min time: 1 hr 40 min time: 2 hrs 40 min www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 5 Luckily, none of the Minnie's move around much. Although some bacteria can move over the surface of agar, meningicocci are good at doing this. So, they’re all stuck sitting in a little pile, but they don’t mind, as long as there’s plenty of sugar to go around. And pretty soon we have a pile consisting of Minnies 8 through 15, all descendents of Minnie the First. And so on. Eventually (after about 24 hours) this pile will be big enough for one of us hulking human beings to see without even using a microscope. This tiny but visible pile is called a colony, and the original Minnie was the original colony-forming unit, or CFU. Of course Minnie was probably not the only CFU around. Over on the other side of the agar, Ginnie was sitting around, minding her own business, enjoying the warmth and sugar, and growing at the same rate. So while a few million descendants of Minnie formed a colony on one side of the plate, a few million descendants of Ginnie form a colony of the other side. And so on, one colony for each original colony forming unit. Comparison of methods We've talked about 3 methods so far: just plain counting under a scope, using a photospectometer to do the dirty work, or growing bacteria in a dish to count the piles of descendants they leave. There is one other way that we could (theoretically) figure out how many cells there are: we could gather them all in one place and weigh them. This would be the biomass method. Biomass is an important way of measuring populations in the lab, but in Frank's case it would not help us -- we would need to collect about 10 million bacterial cells before we could weigh them, and if we could do that, we could probably just cure Frank then and there. So, let's compare the 3 practical ways we have of measuring the infection: Which one requires the least time (for example, the boss wants the answer before lunch)? Which one requires the least effort (think lab intern pain)? Which one can distinguish live from dead cells? And one more question: Direct Count NOT TOO BAD -although counting can be timeconsuming Spec FASTEST -- but only if you already have the calibration curve!!! Viable Plate Count SLOWEST -- we have to wait an entire day for the cells to grow UGH -- counting under a scope gets old fast! WOO-HOO -- very easy to do, even if you didn\'t understand the math -unless of course you're the one that has to make the calibration curve SORRY, you're outa luck SOME WORK -- but most people prefer it to counting under a scope. NOPE, no can do. YES!! That's the genius of this method. www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 6 One day an overzealous intern decided to compare all 3 methods. Here's what she found, but she forgot to label which reading came from which method: 347 organisms/mL 520 organisms/mL 510 organisms/mL Can you tell which reading is which? And what phase of growth (lag, growth, stable, death) is the population in? Which is which? The first reading is definitely the viable plate count, which doesn't include dead cells. And no, you can't really tell the difference between the other two. Lag, growth, stable, death? The population is probably in the death phase, since there are a lot of dead cells around. Why we need to dilute For the remainder of this module, we're going to stick with the Viable Plate Count method -the only method that can tell a live cell from a dead one. But we still have another problem -- the possibility of lots of lots of colonies to count. For example, 500 colonies on a petri dish would look something like this: What if you are trying to count a population in the thousands or millions? You could literally have a carpet of colonies (also known as a 'confluent lawn') growing on your petri dish. This is where dilution saves the day. Not just dilution, but serial dilution... meaning dilution over and over again. Why do we dilute? To have less to count Why do we do it repeatedly? Because we don't know how much dilution we need. Every time we dilute, we'll also make a new plate to incubate. So we might do 5 dilutions and grow up 5 plates. Then we'll end up throwing away 4 of them. Sound wasteful? Well, dilution and plating is quick and easy compared to the pain of starting your experiment all over again. www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 7 Interlude: Diluting Cold Press Coffee So let's see what the process of "diluting" looks like. Here's an everyday example: Cold Press coffee is a superstrong form coffee made without heating the water. The brew starts out with about a zillion molecules of caffeine per cup. In order to actually be able to drink the stuff, you have to dilute it. For example, you could put one cup of cold press coffee into a pot and add 4 cups of water. How many molecules of caffeine are in the pot? a zillion How many cups of coffee are in the pot ? 5 (1 cup of cold press + 4 cups of water) If you pour 1 cup from the pot, how many molecules of caffeine will it have?a fifth of a zillion That would work for a true coffee aficionado, but many of us are less hardy (or more wimpy) so we might want another dilution. Let's take 1/2 cup from the pot, and add 4.5 cup of water to make a wimpy pot. How many caffeine molecules were in the 1/2 cup? 1/2 cup is a tenth of the entire pot, so there should have been one-tenth of one-fifth of a zillion caffeine molecules in the half cup. How many caffeine molecules are in our final (wimpy) pot of coffee? all the caffeine from the half-cup goes into the wimpy pot, and no more get added from the water, so again, onetenth of one-fifth of a zillion. The Sunbucks across the street makes a wimpy coffee with exactly 13,000 caffeine molecules in a cup. Assuming they used the same dilution scheme, how many caffeine molecules were 1 cup of the original brew? Here's the dilution scheme: 1 cup brew + 4 cups water 5 cups strong coffee, then 0.5 cup strong coffee + 4.5 cup water 5 cups wimpy coffee Another way of saying this is, The first time we diluted, we kept 1/5 of the caffeine from the brew The second time we diluted we kept 1/10th of the caffeine from the strong coffee 1/5th of 1/10th = 1/5*1/10 =1/50. So, working backwards, the original brew must have contained 50 times as much caffeine, or 50*13,000 = 650,000 molecules caffeine / cup www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 8 The dilution factor When you're thinking about dilution, it helps to simplify your actions into dilution factors. For example, if you 1. 1 mL coffee + 4 mL water = 1 in 5, or 0.2 dilution factor 2. 1 mL coffee + 9mL water = 1 in 10, or 0.1 dilution factor 3. 1 mL + 99mL water = 1 in 100, or 0.01 dilution factor As you've probably guessed, this works exactly the same whether you're talking about caffeine or meningicocci. Here's what a dilution factor of 0.01 looks like on the lab bench: Notice that it really doesn't matter how much of the original stock you started with, as long as you had at least a mL to put into the new container. What matters is how much you transfer and how much water you add. The dilution factor is then defined as amount transferred / total amount = amount transferred / (amount transferred + amount water added) = 1 / (1+99) = 1/100 = 0.01. Overall dilution What if you do dilute and then dilute again? For example, in our cold press example, the original dilution factor was 1/5, and the second dilution factor was 1/10. So, strong coffee had 1/5th of the caffeine in the brew, and wimpy coffee had 1/5th of 1/10th = 1/50th of the caffeine in the brew. As you can see, it makes sense to multiply the dilution factors to find the overall dilution factor. This works regardless of how many dilutions you do. www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 9 overall dilution factor = dilution factor 1 * dilution factor 2 * dilution factor 3 * ... Over at Sunbucks, the manager would like to make a kids version of the drink that will only have 1/100th of the caffeine of the original brew. How can he do this? He could take the wimpy coffee (dilution factor 1/50) and apply a dilution of 1/2, since 1/50 * 1/2 = 1/100. And how can he achieve a dilution factor of 1/2? He could transfer 1 cup of wimpy coffee and add 1 cup of water. Or if he had a big group coming, he could transfer 6 cups of wimpy coffee and add 6 cups of water. Or there are lots of other ways of making a 1/2 dilution. Could he make the kids drink in some other way (not involving a 1/2 dilution)? Sure, he could start with the strong coffee (1/5 dilution) and make a second dilution: 1/5 * 1/20 = 100. (One cup coffee plus 19 cups water) Or he could do it in two extra steps: 1/5 * 1/5 * 1/4 = 1/100. As you can see, there are lots of ways of getting to the same overall dilution. Back to the lab: (PIC to illustrate) We start with a concentrated stock of meningicocci virus and perform the following dilutions: Add 1 mLto 9 mL water: Dilution factor 1/10 = 0.1 Then, add 1 mL to 99 mL water: Dilution factor 1/100 = 0.01 Then, add 1 mL to 99 mL water: Dilution factor 1/5 = 0.2 What was the overall dilution factor?: 1/10*1/100*1/5 = 1/5000 = 0.0002 As a way to double-check, you can think the dilution process through logically. Often it helps to think through the whole process using some concrete number. For example, if you did two 1/100 dilutions, you could think about it like this: "I started with 300,000 cells in a mL, and put them into 99 mLs of saline, and took out a mL, so there must have been 3,000 cells in that mL. Then I put those 3,000 cells into 99 mLs of saline, and took out one mL again, so there must have been 30 cells in that mL. Overall my dilution must have been to 30 from 300,000, which is the same as to 1 from 10,000 (1:10,000)." Of course, the idea that you started with 300,000 cells is pure fiction, but it can help you make sure that you've done the dilutions correctly. www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 10 How to scale back up "Scaling up" means starting from a sample and figuring out how many were in the original brew, or stock, or whatever was originally there. For example, we can start with a cup of wimpy coffee and figure out how much caffeine was in the original brew. All we need to know is what the overall dilution factor was. In the case of wimpy coffee, it was 1/50, or 0.02. So, when we count the caffeine molecules in a cup of wimpy coffee, we know we got 1/50th of what was in a cup of the original brew -- or in other words, there was 50 times as much in a cup of the original. This method is called multiplying by the inverse (of the dilution factor). If the dilution factor is in the form of a fraction, you can "flip" the fraction (i.e., 1/50 becomes multiply by 50/1). If the dilution factor is in decimal form, multiply by 1 over the decimal (i.e., 0.02 becomes multiply by 1/0.02). Finally, notice that I'm telling you the total number of caffeine molecules ONE CUP of the original brew. If I don't know the actual amount of original brew, I also won't know how much caffeine there was total. Back to the lab Here are some problems, ranging from easy to a bit hard... I did a series of dilutions with an overall dilution factor of 1/20,000, and then plated a grew a 1mL sample. After 1 day, I counted 27 CFUs on the petri dish. How many CFUs would there be per 1mL of the original stock? Inverse of 1/20,000 is 20,000 27*20,000 = ... Answer: 540,000 per mL I did a series of dilutions, with dilution factors of 0.1, 0.1, and 0.01. At the end I plated and grew a 1mL sample, and counted 48 CFUs. How many CFUs would there be per 1mL of the original stock? What's the overall dilution factor? Overall dilution factor = 0.1*0.1*0.01 = 0.0001 Multiply by the inverse... Overall dilution factor = 0.1*0.1*0.01 = 0.0001 Answer: 48 * 1/0.0001 = 480,000 CFUs per mL www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 11 I did a series of dilutions as follows: *1 mL added to 9 mLs water *1 mL added to 99 mLs water *1 mL added to 49 mLs water If the final 1mL sample had 152 colonies, what was the original concentration? The dilution factors were 1/10, 1/100, and 1/50 The overall dilution was 1/50,000 Answer:152 * 50,000 = 7,600,000 cells/mL Why we plate more than one dilution Remember the picture of the hell-to-count petri dish with 500 colonies? No one wants that to happen to them, especially late on a Friday afternoon. But on the other hand, how can we avoid it? Very easily ... while we're doing our dilutions, we just keep plating each intermediate step. Then the next day, we decide which plate looks like the most reasonable for counting. Since we cleverly labelled each plate with its overall dilution factor, we also know how to scale back up to get the original concentration. So, now we finally have all the pieces of serial dilution assembled: Dilute Calculate dilution factor Plate Repeat To make things easier, the standard operating procedure is to go by factors of 10, and to do about 5 or 6 plates altogether. The online version of this module contains an interactive applet which allows you to look at different serial dilutions. To find this applet go to: http://mathbench.umd.edu/modules/cellprocesses_serial-dil/page13.htm So, for example, if I believe that I have about 42 million CFUs per mL, I might want to start with a first dilution of about 1/1000, and plate that. Then I make 4 more 1/10 dilutions, plating each www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 12 one in turn. In the end, I have 5 plates, labeled as shown below. And, if you roll over the image, you will see the plate counts I expect if my original guess (42 million) was correct Picking the plate count For this, we have any easy rule of thumb: the plate you count should have between 30 and 300 colonies. This rule of thumb has the undeniable advantage of being easy to use. But why does it work? Let's imagine that we have a sample with exactly 183,000 cells per mL. And let's say that our technique is flawless. If we count a 1:1000 diluted plate, we should find 183 CFUs (remember, we have magically flawless technique). But the exact same thing would happen if our sample started with 183,001 cells. Or 183,100 cells. Or 183,400 cells. Or 182,800 cells. In fact, even with our absolutely flawless technique, the best we can say is that there are between 182,500 and 183,500 cells. So our absolutely unavoidable error is plus or minus 500/182,000 -- about 0.27%. That's pretty good. Let's look at some other ways we could count the same 183,000 cell sample: Dilution Factor Plate count Resolution Ease of counting 1830 182,950 to 183,050 +/- 50 = 0.027% great!! 182,500 to 183,500 +/- 500 = 0.27% still pretty good 175,000 to 185,000 +/- 5000 = 2.7% not too good 150,000 to 250,000 +/- 50000 = 27% ACK! NOPE, can't do it, this is too much to count 1:100 183 1:1000 18 1:10,000 2 1:100,000 Boring but count-able Easy to count Chimpanzees can count this plate! The more we dilute, the easier the counting, but the higher the error. So you can see that the 30 to 300 guideline is really a compromise between countability and error. Putting it all together The online version of this module contains an interactive applet which allows you to quantify a bacterial population. To find this applet go to: http://mathbench.umd.edu/modules/cellprocesses_serial-dil/page15.htm www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 13 More dilution problems The online version of this module contains an interactive applet which allows you to practice different dilution schemes. To find this applet go to: http://mathbench.umd.edu/modules/cellprocesses_serial-dil/page16.htm And one problem you'll really need to think about... Starting with a dilution made by a TA, you add 1 mL to 49 mLs of water to get a 1:500,000 dilution. What was the TA's dilution factor? Your dilution factor is 1/50 The overal dilution factor was 1/500,000 1/? * 1/50 = 1/500,000 Answer: 1/10,000 Quickies Below, you can practice a couple more times. I also included a few unusual situations ... things do go wrong, of course, and you should be able to recognize that. If you think the dilution series is not valid, click on "re-do the dilution". Oh, and "TNTC" means "too numerous to count". Dilution factor 1:100,000 TNTC 1:1,000,000 674 1:10,000,000 68 1:100,000,000 7 Count Answer Nope! TNTC means "too numerous to count" ! Nope! 674 is definitely more than 250! Yes -- And the answer is ... about 680,000,000 cells/mL Nope! 7 is too few to be valid No, each count is about 10th of the count before it, so the dilution looks good. www.mathbench.umd.edu Dilution factor 1:100,000 Serial Dilution 1:1,000,000 Dec 2010 1:10,000,000 1:100,000,000 1 375 105 11 Nope! 375 is too many to count Something is wrong! The second count dropped only by a factor of 3, rather than a factor of 10 Nope! 11 is too few to be valid page 14 Count Answer Dilution factor 1:100 TNTC 1:1000 1:10,000 Nope! 1 is too few to be valid Yes, you should redo the dilution since the second plate seems to have too many CFUs. 1:100,000 249 24 0 Nope! TNTC means "too numerous to count" ! Yes -- and the answer is 249,000 cells/mL No -- 24 is too few to be valid Nope! 0 is not valid for scaling up 1:10 1:100 Count Answer Dilution factor 954 96 1:1000 10 No, each count is about 10th of the count before it, so the dilution looks good. 1:10,000 0 Count Answer Nope! 954 is definitley more than 250! Yes -- The answer is 9,600 cells/mL Nope! This is too few to be valid Nope! 0 is not valid No, each count is about 10th of the count before it, so the dilution looks good. www.mathbench.umd.edu Dilution factor Serial Dilution 1:10,000 1:100,000 1:1,000,000 TNTC 567 58 Nope! TNTC means "too numerou s to count"! Nope! 567 is definitely more than 250! Yes -- although it looks like there was a problem with the next dilution. The answer is ... about 58,000,000 cells/mL Dec 2010 1:10,000,000 1:100,000,00 0 12 1 page 15 Count Answer Nope! 12 is too few to be valid Nope! 1 is not valid No, although it looks like something happened to the 4th plate, it doesn't affect the plate you will use. Is he dead yet? Remember Frank? He's still sitting on the examining table with a coat over his head. In fact about 50% of people with meningitis will die when the bacterial levels in their blood stream reach 500 / mL. The worried nurse hands you a vial of 10 mLs of Frank's blood. How can you decide whether the infection is at a lethal level? What counting method will you use? Unfortunately, a direct count or a photospec would require separating the meningicocci from the red blood cells. If we could do that, we could probably just cure poor Frank. So we're stuck with a viable plate count. What dilution scheme will you use? We need to get plate counts between 30 and 300, and we think that the concentration in his blood might be as high as 500 per mL, but it could be much lower. So, we should go ahead do the first plate without even diluting! After that we could do standard 1/10th dilutions. How many dilutions do you need? You definitely need at least 1 dilution, in case Frank is somewhere in the 300 or 400 per mL range. Without a dilution, that wouldn't be countable. But really, a single 1/10th dilution would suffice. If Frank has >300 colonies in a 1/10th dilution, he has >3000 actual cells per mL, and that would be fatal. (Of course, he'd also be dead, but let's not be morbid). www.mathbench.umd.edu Serial Dilution Dec 2010 page 16 However, you could keep going with a standard 5 dilutions and not waste much time or energy, plus it would allow you to make an accurate estimate regardless of his actual level of meningicocci in the blood.