The Incoherent Left

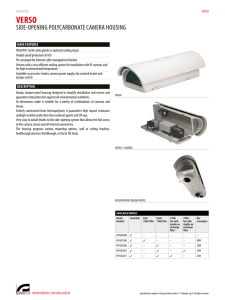

advertisement

The Incoherent Left By Todd Gitlin Chronicle of Higher Education, Chronicle Review, Jan. 23, 2011 Once upon a time, in a century far, far away, there was an idea of a single, interconnected left in a single, interconnected world—a unified force, or a vanguard, or a virtual chamber of the deputies of the people, some entity whose mission was to lead the way toward the realization of a collective and universal ideal. In one sense, the origin of this grand metaphor lay in the millenarian monotheism shared by the three Abrahamic religions. In an earthier way, it lay in the seating arrangements of the post-Revolution French Parliament, which positioned the left as the party of the future against the right, which stood for the already done, the established, the past. Just as time was bifurcated into past and future, teetering on the knife-edge of the present, so were the two tendencies. This was not—there never is—an idea without precedent. The past had been full of struggles for justice and equality. But only occasionally did seers hazard the notion that there was a single, overarching, or undergirding structure to all of them. One attempt to formulate a common root was the couplet attributed to John Ball, the English priest who helped inspire a peasant revolt in 1381: "When Adam delved and Eve span/Who was then the gentleman?" (No small inspiration: The 1888 novel A Dream of John Ball was written by a founder of England's Socialist League, William Morris.) The colonists gathered in Philadelphia in 1776 held it "self-evident" that "all men"—not just white men, Englishmen, propertied men, men of the late 18th century, or denizens of the Northern Hemisphere—are "created equal." Then Marx lent the idea a universal and analytical as well as normative sweep—perfect for an age of globalizing production, communication, and culture—with the ingenious proposition that history was passing into the grip of a single, unitary agent of change and deliverance. He borrowed Hegel's imagery of the "universal class" to posit that history—all of it— tended toward a grand, apocalyptic conclusion in which distinct conflicts would be subsumed into the Final Conflict, to be won when all the oppressed were gathered by inexorable processes into one Big Class to End All Classes. For roughly a century and a half after Marx and Engels's Communist Manifesto, the left—or, if you like, Left—was more or less the name for those who honored and heralded that One Big Class. Even a good deal of 19th- and 20th-century nationalism was motivated by the idea that in seeking the independence of their respective nations, hitherto colonized, imperialized peoples were pursuing a universal project—the peoples were willy-nilly a people in the making. The lyrics might vary from place to place, but under the tutelage of One Big Party, the melody would be the same. Beginning in 1960, the editors of London's New Left Review began composing the theoretical music for a revised revolution, and they hit their stride as Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, and Mao Zedong strived to conscript the global South into a sort of universal liberation front, and some Westerners fancied themselves its allies. In 1970, the New Left Review spun off a publishing company, Verso, from which now emerges The Verso Book of Dissent: From Spartacus to the Shoe-Thrower of Baghdad. "Dissent" is the new rubric—a chastened choice in the post-1989 world—but then where shall the editors, Andrew Hsiao and Audrea Lim, draw the line? The book, an anthology of quotes and excerpts to commemorate Verso's 40th anniversary, superficially looks like a heap of loose ends, but it is both more and less. Tariq Ali writes in his preface that the figures who appear in the book are the "dissenters and rebels who have attempted to move mountains, to improve, change, transform the world since the earliest times." But if the category of world-changer is to be so all-welcoming, why not Mussolini, who in his own way "attempted to move mountains, to improve, change, transform the world"? Why honor the black nationalist Robert F. Williams but not the organizers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee? Why toss a credit to the Stalinist hack Louis Althusser for having called Spinoza "the first materialist thinker" (was Democritus chopped liver?). It's good to represent the ex-colonial world, but why a Palestinian poet who heralds "the glory lost since Umayyad conquests"? Why reproduce bumpersticker slogans from groups like the Crips and Bloods, while omitting Albert Camus? Why may kibbutzniks not apply? Why honor the Sartre who declined the Nobel but not the Sartre who for decades defended the State of Israel's right to exist? There is plenty of agitprop in this collection, but explanations are wanting for how saints become sinners and what the two might have to do with each other. When does the Mao celebrated in 1927 for declaring, "Down with the local tyrants and evil gentry! All power to the peasant associations!" pass over into the Mao satirized in 1961 as an oppressor of the masses? The editors strain to represent bottom-up rhetoric, however boilerplate, and select cultural snippets (John Lennon at his most banal) alongside high-flying theory. A passage from Foucault, harnessing forces of control to forces of resistance in "perpetual spirals of power and pleasure" (his italics), is followed two pages on by Adam Michnik celebrating "the end of the utopian dream," which in turn is followed, five pages on, by a hope for "peace with social justice" expressed by a Peruvian community organizer assassinated by the Maoist Shining Path. Lenin is celebrated; then, poker-faced, a few pages on, so are the rebellious sailors of Kronstadt. Perhaps the principle is that boilerplate is admissible as long as it is Manichaean, as when Bolivia's president, Evo Morales, speaks of "the confrontation of two cultures: the culture of life represented by the indigenous people, and the culture of death represented by the West. I believe only in the power of the people." Hugo Chávez makes a show of dispelling the sulfuric fumes left on the United Nations General Assembly rostrum by George W. Bush, and declares "readiness to fight to save the world and build a new and better world." Seven pages later, the book quotes from an anthem of Iran's Green Movement, which arose to oppose the "allegedly fraudulent presidential election results" that renewed the tyrannical power of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, ally of ... Hugo Chávez. Does one big movement enfold Hugo Chávez and the democrats of Tehran? The Verso Book of Dissent is a project that not only does not cohere, but also cannot. History is too messy to fit a grand story of Establishment vs. Dissent. Does Tristan Tzara, who rants "against action," who "hate[s] common sense," really belong to the same One Big Union with Eugene V. Debs who, on the next page, heralds "the rise of the toiling masses"? And what do they have to do with the Internet guru John Perry Barlow, telling "Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel" that he comes "from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind"? Is it not, to say the least, problematic to tell "the past to leave us alone" in a volume that celebrates tradition? For the sake of ecumenism, it is helpful to see the former Sandinista vicepresident Sergio Ramirez acknowledging that his government "many times los[t] a proper perspective of ... what was just and desirable," that fell into the hands of "power in perpetuity." But then it is also interesting to see where the editors' limits lie. They quote Albert Einstein when he opposes the terrorist Menachem Begin in 1948, when he writes compellingly about socialism in 1949, when he co-signs a humanist, anti-cold-war manifesto with Bertrand Russell in 1955, but not during the many occasions when he declared himself a Zionist. It would seem that one single nationalism in the world is not admissible to the editors' almost-United Nations, though a banal 1997 anti-Oslo Accords statement from an official of the theocratic Hamas is found worthy of inclusion, as is a simple-minded statement in favor of boycotts, divestments, and sanctions against a certain nation whose name must not be spoken. Often enough, The Verso Book of Dissent resembles the 16th-century Foxe's Book of Martyrs, in which a sort of unity was composed from the premise that what Christians (mainly Protestant) had in common was less what they believed than what was done to them. It was popery that unified the potpourri. Later, it was European empires. And now? "The left" exists in quotation marks. Lacking coherence, The Verso Book of Dissent heads smack into an intellectual dead end. Nothing unique there: The right suffers its own incoherence. But in a time of ideological decomposition, it would be good to see people so sure of themselves come down from their high horse. Todd Gitlin is a professor of journalism and sociology at Columbia University. His latest book, with Liel Leibovitz, is "The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election" (Simon & Schuster, 2010). His novel, "Undying," will be published next month by Counterpoint.