CUTTING EDUCATION SLACK

advertisement

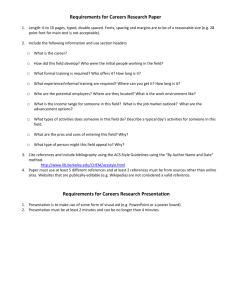

CUTTING EDUCATION SLACK-POLICY DECISIONS Key points: summary -The evidence base for career guidance in schools, gained from Dept of Education and Skills’ evaluation reports and from other (ESRI, FORFAS, NGF) public surveys in Ireland, suggests that more time and not less should be provided for career guidance in schools -Studies undertaken by economists of the cost-benefit effects of career guidance suggest that school career guidance provision contributes significant returns to the economy across a range of outcomes, and, at a minimum, pays for itself -Career guidance provision in schools contributes to the achievement of a range of public policy economic and social goals including educational and labour market efficiency and social equity -The Budget 2012 cut to career guidance services in schools will obstruct the requirement for schools to implement the relevant section of the Education Act -The governments decision to cut career guidance services to schools runs completely contrary to international principles/values/positions (EU Council of Education Resolutions, European Social Charter, ILO Recommendation on Human Resource Development, OECD’s policy review findings) which Ireland is party to -Evidence from countries (New Zealand, Netherlands, England) where schools are given responsibility for the provision of career guidance at their discretion shows hugely negative results -Evidence from countries with high performing education systems (Finland, Singapore) shows career guidance as an integral part of education provision, well resourced and with qualified staff -In addition to the economic, educational, employment and social consequences of the cuts alluded to above, direct consequences will be the end of free public career guidance services, the development of private sector guidance for those who can afford to pay, inequality of opportunity and of progression, inequality of access to comparable services. Introduction Governments make policy decisions. Citizens’ lives are affected. How can we know whether those decisions are good ones or not? Six characteristics of good policy development stand out: consultation with stakeholders, consideration of evidence – particularly economic cost-benefit, political/social ideology, legal obligations, international references and international comparative evidence. Let us consider the recent Budget 2012 decision to eliminate the ex-quota career guidance1 posts in secondlevel schools against each of those good policy development characteristics. 1 School career guidance provision in this article refers to a range of career learning activities that assist young people (and their parents) to make informed and meaningful educational and occupational decisions and transitions/transfers. Such activities include career counseling, career classes, work experience, work shadowing, work simulation, workplace visits, careers talks, parental consultation, consultation with teaching colleagues, aptitude and occupational preference testing, and where appropriate, counseling on personal issues that may affect educational performance and educational and career choices. 1. Consultation with stakeholders The major stakeholders in the education/career guidance field are students and parents who are the direct beneficiaries and users of publicly funded education and career services. They were not consulted either formally or informally on the Budget 2012 decision. Indirect beneficiaries are other teaching colleagues, school managements, further and higher education and training institutes and organisations, employers, and taxpayers. They were not consulted. 2. Evidence base School inspection and public consultation evidence The evidence base for policy decisions for career guidance in schools available to the Department and the Minister comes from several sources, none of which point to eliminating career guidance: the Department’s own Inspectorate of Guidance, opinion research undertaken by the ESRI and others, and opinion research from other public consultation exercises undertaken for the National Guidance Forum and for the Expert Group on Future Skill Needs (FORFAS). The report of the Department’s Inspectorate, Looking at Guidance2 based on 55 school inspection reports and on discussions with all school partners in those schools, concluded that a high quality of career teaching and learning took place through a range of educational experiences managed by the guidance counselor. It noted that more attention should be paid to Junior Cycle students and that some schools did not use the full guidance allocation for the purpose of guidance and that a few used unqualified/untrained staff. In the ESRI’s longitudinal study From Leaving Cert to Leaving School3, students expressed positive perceptions about career learning experiences in school but were critical of the limited time available for individual career discussions due to the guidance counsellor’s dual role of subject teaching and career guidance. The report highlighted the need to target career activities to Junior Cycle as decisions made there had significant impact for Senior Cycle and post Leaving Cert learning and work opportunities. Perceptions of the General Public on Guidance Services4 was a study undertaken on behalf of the National Guidance Forum. The majority of people who participated in the study reported their experience of career guidance in school as being very helpful or helpful, again stressing the importance of targeting Junior Cycle. 2 Department of Education and Science Looking at guidance-teaching and learning in post-primary schools Dublin: DES, 2009 3 Education and Social Research Institute From Leaving Certificate to Leaving School Dublin: ESRI, 2011 4 National Guidance Forum Perceptions of the general public on guidance and guidance servicesconsultative process report Dublin: NGF, 2007 Respondents to Careers and Labour Market Information in Ireland5, a study commissioned by the Expert Group on Future Skill Needs (FORFAS), stated that guidance counselors were the most helpful source of careers information and the easiest way to access such information. Respondents also expressed a preference for individual career counseling. The report concluded that given the key role of parents in young people’s career choices, the best way to reach parents with careers and labour market information was through the schools network. Conclusion: The evidence base available to the Department and to the Minister at the time of the Budget cut shows that more and not less ex-quota school time is required to provide career guidance in schools, and in particular at Junior Cycle. Evidence studies of the economic value of career guidance6 Two studies on the economic value of career guidance have recently been undertaken by economists in Northern Ireland and in Scotland. In 2008 the Educational Guidance Service for Adults (EGSA) had the economic value and impact of its work examined by Regional Forecasts, a division of Oxford Economics Ltd. The findings showed the employment outcomes attained through career guidance provision to adults produced net additional tax revenue of 9.02 GBP for every 1 GBP of public money invested in the service7. Careers Scotland (2007) used DTZ Consultants to address the question: does career guidance make a difference? It examined this from the perspectives of both outcome measurement (learning, economic and social) and the impact of its work with young people and adults. The findings8 show that someone who has received career guidance is more likely to: - gain a qualification, have stronger educational ambitions and expectations, and more likely to have achieved an advanced qualification (learning outcomes) - be in a job, stay in the workplace and be financially successful (economic outcomes) - experience higher confidence levels, especially young people from a lower socioeconomic background (social outcomes). The combined impact of those outcomes was estimated at 250 million GBP per annum in Scotland, a country with a population of 5.2 million. Conclusion: While no similar study has taken place in Ireland and while there are some differences in terms of inputs, data from neighboring countries suggest significant economic benefits from the provision of career guidance. One can safely 5 FORFAS-Expert Group on Future Skill Needs Careers and labour market information in Ireland Dublin: FORFAS, 2006 6 In the context of the government’s new approach to allowing schools the discretion to decide what they wish to provide to students as core curricular learning experiences, such as career learning, it is important for government to be able to show the value to the economy (cost-benefit ratios) of each area of the core curriculum, particularly in a tight Budget situation 7 EGSA Examining the impact and value of EGSA to the NI economy Belfast: EGSA, 2008 8 Careers Scotland Demonstrating Impact-Final Report Edinburgh: Careers Scotland, 2007 hypothesize that the careers guidance service currently provided in schools in Ireland at a minimum pays for itself. Taking into account the economic value and impact of the broader learning, employment and social outcomes of career guidance as illustrated in these studies, it is very difficult to understand the decision of Budget 2012 to cut career guidance. 3. Political values: the contribution of career guidance to public policy goals Career guidance in schools is not just about helping individuals and their parents. It is a socio-political activity that plays a significant role in achieving some of the public policy goals espoused by present and past governments. Career guidance in schools contributes to learning goals/benefits by improving the efficiency of education systems. It contributes to increased educational access, school achievement and course completion rates at second level education. But such investment of a preventive nature at second level has a critical economic value for participation, motivation, and course completion at further and higher education and training levels where only ten years ago the annual costs to the taxpayer of noncompletion and early drop-out (without counting the cost to individuals and their families) dwarfed the 32 m. euro spent annually on career guidance provision9. Labour economists have long recognized the role that career guidance can play in labour market efficiency. Career guidance can improve the match between supply and demand by helping young people to search for a better fit between their interests, abilities and qualifications, and the available work opportunities. It also helps them to consider learning new skills for new/emerging occupations. As educational and labour market pathways become increasingly complex in nature and increasingly involve local, regional, national and international dimensions, career guidance is more critical than ever. Career guidance contributes to social equity goals. It helps to ensure that education and employment opportunities are distributed equitably, and that people make maximum use of their talents regardless of their gender, social background or ethnic origin. Certain sections of the population are likely to be less familiar with educational and labour market information than others, and need more help in overcoming barriers to accessing these opportunities. Conclusion: The Budget decision to cut career guidance services to schools runs completely contrary to stated Irish government public policy goals in the education, employment, and social spheres, and will ultimately hurt its knowledge economy aspirations. 9 We tend to forget that one of the functions of career guidance at second level is to produce efficiency of transfers to further and higher education and efficiency of student performance once they get there. View: NCGE Staying power: colloquium on increasing retention rates in higher education Dublin: NCGE, 2000 4. Legal obligations Schools are required by Section 9 (c) of the Education Act to “ensure that students have access to appropriate guidance”. What this looks like in reality is spelled out in the Department’s Guidelines on the implications of the Act10. The Guidelines cover (i) the aims and importance of guidance and counseling provision, (ii) the planning of a school guidance programme, (iii) elements of the school guidance programme, and (iv) resources and supports for guidance. Given the Budget decision to withdraw the ex-quota staff resource for guidance in schools, the Guidelines are now just aspirational. It leaves schools with no way to turn the Education Act guidance requirement into a reality for students and parents. The Budget cut in fact makes a mockery of the Act and of the Guidelines. 5. International reference points: review findings and common principles In developing policies for education, employment and social equity, governments take as reference points international review findings, policy indicators, and commonly agreed principles and values, particularly as a Member State of the European Union. The following is a brief summary available to the Department of Education and the Minister, all of which require that particular attention be paid to the provision of career guidance for the achievement of public policy goals. OECD The OECD is often used by Education ministers in Ireland as a stimulus for reform of social (includes education) and economic policy areas. The OECD undertook its last review of policies for career guidance in 2001-3, covering 14 countries that included a country review of Ireland at the invitation of the Department. In its conclusions on Ireland, the OECD referred to the strengths of career guidance provision: -a solid legislative base -a climate that favours initiation and experimentation -a committed profession, and -a service well received among the population11. The OECD’s final report12 highlighted the importance of career guidance provision in schools: “…career services are necessary for effective transition systems…. career management skills are an essential literacy alongside other literacies for successful transitions into, within, and from education, training and work”. World Bank In its review of policies for career guidance in developing and transition economies,13 the World Bank suggested that as such economies develop and restructure, the provision of career guidance can be an important ingredient in supporting social and economic development. 10 Dept. of Education and Science (2005): Guidelines for Second Level Schools on the implications of Section 9(c) of the Education Act (1998), relating to students’ access to appropriate guidance. 11 OECD Review of Career Guidance Policies-Ireland Country Note Paris: OECD, 2002 12 OECD Career Guidance and Public Policy-Bridging the Gap Paris: OECD, 2004 13 World Bank Policies for Career Development Washington DC: World Bank, 2004 International Labour Organisation Member states (including Ireland) agreed the Human Resources Development Recommendation of 200414 to assure and facilitate citizens’ access to career guidance and information throughout their lives including through ICT, to involve a range of stakeholders in such provision, and to promote the role of enterprise in increasing growth and decent jobs. European Social Charter (revised 1996) Article 9 of the European Social Charter refers to European citizens’ right to vocational guidance. Signatories to the Charter including Ireland undertook to provide a service to assist persons to solve problems related to occupational choice and progress, and that such a service should be free of charge to young people, including school children15. The EU Council of Education Ministers The provision of career guidance in a lifelong learning context has been the subject of two EU Council Resolutions, the first proposed under the Irish Presidency in 2004 and the second under the French Presidency of 2008. The 2004 Resolution16 noted the importance of career guidance in schools: “Guidance provision within the education and training system, and especially in schools or at school level, has an essential role to play in ensuring that individuals’ educational and career decisions are firmly based, and in assisting them to develop effective selfmanagement of their learning and career paths. It is also a key instrument for education and training institutions to improve the quality and provision of learning”. The 2008 Resolution17 confirmed the importance of career guidance in assisting citizens through multiple transitions, particularly from school to vocational education and training, higher education, or employment. Other Resolutions of the Council: Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (2006)18, New Skills for New Jobs (2007)19, and the Joint Progress Report of the Council and the European Commission on delivering lifelong learning for knowledge, creativity and innovation (2008)20 all noted that particular attention must be given to lifelong/career guidance. Conclusion: It is very clear that the Budget cut on career services in schools runs completely contrary to European social policy values and education positions to which it is a party and to international knowledge and experience. 14 http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?R195 Council of Europe European Social Charter Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 1996 16 http://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/2010/doc/resolution2004_en.pdf 17 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/educ/104236.pdf 15 18 OJ L 394, 30.12.2006, p.10 OJ C 290, 4.12.2007, p. 1 20 Doc. 5723/08. 19 6. International comparisons: evidence from experiences on devolving responsibility for career guidance provision to schools We already have evidence from the Department’s Inspectorate’s report (see Section 2 above) that under existing devolution arrangements, some schools do not use all of the ex-quota guidance allocation for guidance purposes – they divert it into subject teaching, and that some schools use unqualified/untrained staff to provide a service. With the Budget cut, one can expect that schools will quite quickly have to use existing guidance counselors for subject teaching part-time or full-time, and that, within a year or two, all existing guidance counselors will be full-time subject teaching. This will be an unsurprising consequence of schools no longer having a separate staff resource allocation for career guidance. As the recent Department circular nicely put it “schools will have discretion to balance guidance needs with the pressures to provide subject choice.” (emphasis added). In that context it is worth examining how this discretion, through devolved decisionmaking to school management on career guidance provision, has operated/operates in other countries. Here are some examples. 6.1 New Zealand In New Zealand, a country of comparable size to Ireland, schools are legally required to provide careers education to all students. How they do it is at their discretion. School principals tend to appoint long-serving subject teachers to the position of Careers Advisor on a part-time basis for which they are awarded a management allowance in addition to their teacher’s pay. Nearly all of the teachers appointed to the position are untrained and unqualified21. The public perception (students, parents in particular) of the service provided is generally negative22. Successful completion rate at upper secondary education is significantly less than in Ireland23. While participation in tertiary education (VET and further education) is high by OECD standards, completion is low and there is concern about tertiary course drop out. There is general public concern that young New Zealanders do not have the knowledge and skills sets for a knowledge based economy. 21 A New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) national survey of careers staff in schools found that just 15% of respondents had a careers qualification in addition to their teaching qualification (a further 6% were studying towards a careers qualification). It also found that two-thirds of careers staff had been teaching for more than 16 years, making them longer-serving than their teacher counterparts when compared with findings from the 2006 NZCER National Survey of Secondary Schools (See Vaughan and Gardiner (2007) Careers Education in New Zealand Schools. Wellington: NZCER). 22 Education Review Office The Quality of Career Education and Guidance in Schools. Wellington: ERO, 2006. The ERO reported that only 12% of schools provided high quality careers education and guidance to their students. All schools are given a Careers Information Grant to cover internal staff costs, resources, and travel for careers staff. Many schools use it for unrelated purposes. 23 OECD Education at a Glance 2011 Paris: OECD, 2011 6.2 Netherlands24 Career guidance provision in schools in the Netherlands developed historically as extra paid duties for any subject teacher for hours in addition to his/her teaching load. There was no requirement for the teacher to have a qualification. Since the 1990s this approach has been replaced by giving schools a grant to use as they wish to provide career guidance in schools. As in New Zealand, this discretion has led to schools purchasing services from outside the school or not at all. There is no quality assurance of provision. Student perception of career guidance in schools is very negative. Participation, completion, and achievement rates at all levels of education and vocational training are major public concerns. Significant numbers of students change courses after the first year of higher education. 6.3 England Schools in England have statutory responsibility for the provision of career guidance. But schools must pay for this from their existing budget-they receive no specific allocation for guidance provision. They are required by the Department to purchase it from an independent impartial source and this may include unqualified sources. Equally schools can refer pupils to online resources and that will meet their statutory responsibility. The net impact is that there is huge variability among the career learning experiences of students according to the school he/she attends. This is evident from the following results of the FutureTrack longitudinal study where in response to questions about access to careers guidance and information prior to applying to higher education, first year higher education students reported25 that they did not have enough or none at all of: -individualized career guidance: 48% -classroom guidance: 54% -information on alternatives to HE: 52% -information on the relationships between courses and jobs: 60% -information on the range of HE courses: 58% -information on the implications of subject choices post age 16: 74%. 6.4 Conclusions on the discretionary approach It is very clear that a discretionary approach that includes giving resources to schools to provide career guidance to students produces a hit and miss result. A young person (and their parents) may be lucky or not, depending on the school he/she attends. There may be a service or not, from a qualified person or not. The service may be quality assured or not. In essence the discretionary approach promotes inequality of access to services for school students (and parents) and inequality in obtaining comparable career learning experiences and quality assured experiences. The effects of such inequities will be more marked in schools in Ireland where no separate staff resource allocation for career guidance will be given to schools from next August. 24 McCarthy, J. Het Ontwikkelen van het personeel van morgen:een reflectie op de huidige stand van zaken rondom loopbaanbegeleiding in Nederland’s (trans. Developing the workforce of today and preparing the workforce of tomorrow – a reflection note on career guidance provision in the Netherlands)-Hertogenbosch : Euroguidance Nederland, 2008 25 Higher Education Careers Service Unit and Warwick Institute for Employment Studies Applying for Higher Education – Career Choices and Plans Manchester: HECSU, 2007 7. Evidence from high performing countries (OECD education indicators) When making policy decisions in education, it is prudent to examine evidence from high performing countries as per the OECD indicators of the performance of education systems. Here are two examples. Finland26 In Finland, guidance is a compulsory subject within the curriculum, and each school must produce a plan indicating how the relevant goals are to be reached both by all teachers and by the school counsellors. All comprehensive schools have at least one fulltime-equivalent counsellor, who has normally had a five-year training as a teacher, plus teaching experience, followed by a one-year specialist training; alternatively, guidance can be selected as an option within the five-year initial teacher training. Their role includes individual career counselling, and running guidance classes focusing on careers education and study skills. In addition, most pupils have at least two one-week workexperience placements. Alongside this, pupils have access to career guidance provided by vocational psychologists within the Ministry of Labour: they have had six years’ training as psychologists, plus a 55-day specialist vocational training. There are clear guidelines for comprehensive and upper secondary schools, specifying the minimum level of guidance services permissible, together with a web-based service to support institutional self-evaluation of guidance services. Steps have also been taken to embed guidance policy issues in national in-service training programmes for school principals. Singapore In Singapore, the career guidance counsellor’s role tends to be a co-ordinator of a more broadly based careers programme. There is strong emphasis on individualised guidance, as part of a policy of implementing an ‘ability-driven’ education that seeks to develop the full spectrum of talents and abilities in every child in school. More recently, a developmental programme of Education and Career Guidance (ECG) has been introduced, with primary schools focusing on career awareness, secondary schools on career exploration, and upper secondary schools on career planning. This is delivered through a variety of means, including career education lessons, counselling, talks, workshops, visits, work experience/shadowing, projects, e-resources and career portfolios. In addition, each school has a school counsellor plus teacher-counsellors, who may provide some career counselling to pupils. Conclusion: In countries with high performing education systems, well developed career learning provision forms an integral part. Schools are well resourced with specific staff allocations for career guidance provision and well qualified staff. Career learning is part of core curriculum learning. 26 For more details on Finland and Singapore, see Watts, A.G. The Emerging Policy Model for Career Guidance in England: Some Lessons from International Examples Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, No.27, November 2011, pp.32-39 8. Summary and conclusions In making major policy decisions in a western democracy, good government requires that consideration is given to the target group for whom the decision is intended and to the consequences for this group. The economic costs and benefits are weighed up and normally the economic benefits, immediate, short-term and long-term, should well outweigh the costs. Joined up government thinking, a good practice in any government, requires other types of benefits such as social outcomes to be considered. This is particularly true in social policy areas where the cost of remediation is always hugely more expensive than the cost of prevention. As a means of increasing the PTR (pupil teacher ratio), the Budget 2012 decision to cut the career guidance allocation to schools does not pass any criteria of good government and makes no economic or social sense. There is not a shred of national or international evidence, or any principles or values that support this move. The cut places the Irish education system back to the 1960s when no career guidance service was provided in schools. It is as if time has marched on in respect of the complexity of education and labour market pathways but the Government has not. The government response to a problem (increasing the PTR to improve public finances) for which it has other optional solutions looks like a Dark Ages response in light of the knowledge and information society in which we now live. It is back to a time of trial and error in making education and employment choices. With schools unable to provide what students have received as a free public service up till now, parents will have to look to the private sector for career guidance and to pay for it, at a time when those who are lucky enough to be employed find diminished pay packets with additional taxes to pay for the failed banks and poor bank regulation. Equality of opportunity, equality of access and progress in education and employment have slid off the political table with one stroke of the Minister’s pen. Was it a decision to cut slack in education or just a slack political decision? I leave the reader to decide. Dr John McCarthy, Director International Centre for Career Development and Public Policy c/o Careers NZ 4th Floor CMC Building Courtenay Place Wellington New Zealand Email: jmc@iccdpp.org www.iccdpp.org Tel: 006449770367 Mobile: 0064211342397 25 January 2012