Poor Law Amendment Act, 1834 - Beechen Cliff School Humanities

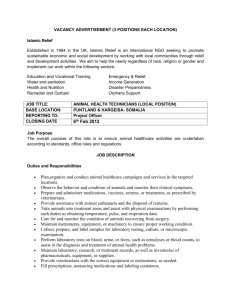

advertisement

Poor Law Amendment Act, 1834 AS British History Depth Study - Poverty By Mr R Huggins Government Response to Poverty Throughout history governments have debated about how they should deal with poverty and decide who should be entitled to help from the community. Today everyone in Britain pays into the National Insurance scheme. If someone loses their job they are entitled to receive unemployment benefit for six months so long as they are looking for work. Once your six months are up you then transfer to another benefit which is based upon your income and takes into account how much savings you have. Whilst you are unemployed you can receive all sorts of benefits and discounts ranging from housing benefit to reductions in Council Tax. The government closely monitors your attempts to find work through a network of job and benefit centres. If you become what is called ‘long term unemployed,’ the government will link your benefit to attendance on work training schemes that are aimed to get you back into work. This system has its critics. On the one hand people object to the high social cost and taxes of providing benefit for people who are unemployed, whilst others argue that unemployment levels can make it very difficult to find work. They point out that if you don’t help the unemployed and people living in poverty then it leads to social unrest and high levels of crime. During the twentieth century this debate was particularly intense during periods of economic depression. For example, during the Presidential Elections of 1932, the two main political parties were split between the Republicans on the Right, led by Herbert Hover, who believed in Rugged Individualism; and the Republicans on the left, led by Roosevelt, who believed in Government Action to end the Depression. A famous Republican quote from this period said ‘If you want a dog to hunt let it go hungry, if you want a man to find a job, let his family go hungry and he will soon find a job.’ A similar attitude could be found amongst some politicians today. This ‘liaise faire’ attitude towards economics and poverty began in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century when the population of Britain began to rapidly increase along with the cost of providing for the poor. The focus for the debate was how to reform the existing Poor Law, which had been passed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, to deal with the threat of ‘able bodied beggars.’ The key principle which had underpinned this system was that the local communities were responsible for the poor and unemployed from their own town or village. Three hundred years later, this system was in need of reform and not suit the needs of a country moving away from agriculture towards a largely urban, industrial economy. One of the features of this period is the changing attitudes towards change. In the past people respected the traditions of the past and were unwilling to make significant changes. The new scientific revolution and age of enlightenment led to people questioning everything in a bid to find better ways of doing things. Page 2 Government Response to Poverty The Age of Reform The age of reform is a term used to describe British politics during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with special focus on the years between the fall of Lord North in 1792 and the passing of both the Great Reform Act of 1832 and the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834. Politics in this period were dominated by two political parties, the Tories and the Whigs. Opinion was often split within these two groups, but as a rule Whigs were advocates of change as well as civil and religious liberty, whilst the Tories were defenders of court, Church and established institutions. Both groups clashed on critical issues of the time such as Catholic emancipation, parliamentary and economical reform, the royal prerogative, ministerial conduct and public order. The French Revolution had a profound impact on British politics. Initially, the French experimented with a constitutional model similar the British Monarchy. Many politicians, especially amongst the Whigs welcomed these changes. However, with the execution of Louis XVI, The Reign of Terror and Napoleon’s attempt at world domination, there was a conservative backlash against radical change, which benefited the Tories. With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, both the industrial the agricultural sectors of the British economy went into depression with the import of cheaper goods from abroad. At the same time over 400,000 troops were demobilization and along with the introduction of new machines, this led to an increase in unemployment and social unrest. This prompted the government to introduce the Corn Laws and various import duties (tariffs), which tried to protect British farmers and industries. These changes resulted in higher prices which were unpopular with working class people. The French Revolution had let the genie out of the bottle. High prices and low wages led for increased calls for change amongst the working and middle classes. There was a real fear amount the upper class that unless the middle classes were given the vote, this social and economic unrest could turn into revolution. This fear helped to drive the 1832 Reform Act through Parliament and led to a new age of reform based on utilitarian and humanitarian ideas. These two competing ideas led to debates in Parliament that introduced laws which regulated factories, new housing, mines and changed the administration of the Church of England and local government. The Key focus of these changes was to find ways of reforming British society to make it work smoothly and to avoid a potential revolution in the future. Both the Poor Law Amendment act of 1834 and the later Public Health Acts were key pieces of legislation which were designed to reform British Society for the benefit of everybody, although they were very controversial at the time, Page 3 Government Response to Poverty The Elizabethan Poor Law During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the government was frightened by the emergence of what was termed the ‘able bodied beggar.’ The changes to religion, agriculture and society had increased unemployment and poverty. Large bands of men used to roam the countryside in search of work. This led to all sorts of social problems including high levels of crime and begging. The 1601 Elizabethan Poor Law divided the poor into two groups 1. The impotent poor - the sick, elderly, those unable to work due to the seasonal nature of agricultural work - who were to be helped via outdoor relief or either almshouses or poorhouses. These people were classed as 'would work but couldn't'. 2. The other group was labelled as the 'able-bodied beggar' who could work but wouldn't'. This group was to be put to workhouse or house of correction and severely beaten until they realised the error of their ways. Page 4 Government Response to Poverty Key Features of the Old Poor Law It relied on the parish as the unit of government, and therefore on unpaid, non-professional administrators. Parishes were small and their finances were feeble so unusually heavy burdens such as those experienced between 1815 and 1821 would be disastrous at parish level Overseers or Justices of the Peace might be petty despots. Elizabethan Poor Law’ aimed to provide social stability, to alleviate discontent and distress and to prevent riots and disaffection through outdoor relief. As the system of poor relief developed, not all parishes had a poor-house or house of correction. It soon became obvious that some parishes were more sympathetic and generous towards their poor. This led to economic migrants and resulted in paupers moving from less generous parishes to ones which were more generous. To prevent this, parliament passed the 1662 Settlement Act which stated that a person had to have a 'settlement' in order to obtain relief from a parish. This could be secured by: Being born in the parish Marrying someone who came from that parish. Working in the parish for a year and a day Under this new law, if a labourer moved away from his parish of origin in search of work, then his local JPs had to issue him with a certificate of settlement saying that if he fell on hard times, his own parish would receive him back and pay for him to be 'removed'. The 1662 Settlement Laws caused problems: They hindered the free movement of labour, which is vital to an expanding industrial economy. They prevented men from leaving overpopulated parishes in search of work on the 'off-chance' of finding employment. They led to short contracts of, for example, 364 days or 51 weeks. A man might live in a parish for 25 years, working on short contracts, and still not be eligible for poor relief later in life. Improvements to agriculture meant that fewer people were needed to work on the land in the countryside. The new factories and coalmines were desperate for labour during times of prosperity. During times of depression, some of the unemployed had to return home to parishes, which could barely afford to support them. Page 5 Government Response to Poverty 1782 Gilbert's Act – Early Poor Law Unions Under the Elizabethan Poor Law, some parishes struggled to find the money to build a poorhouse or house of correction. In 1782, after 17 years of campaigning an MP called Gilbert finally managed to persuade Parliament to pass a law which allowed parishes, if they wished to form a Poor Law Union to share the costs of building a workhouse or a house of correction for the poor in their area. These Poor Law Unions were successful in helping to cut costs in the areas where there were set up, but the workhouses they set up were not always very well run or regulated as the Royal Commission found out during its investigation under Edwin Chadwick in 1833: Report from the Commissioners Inquiring into the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws, 1834, p. 303 In parishes overburdened with poor we usually find the building called a workhouse occupied by 60 or 80 children (under the care, perhaps, of a pauper), about 20 or 30 able-bodied paupers of both sexes, and probably an equal number of aged and impotent persons, the proper objects of relief. Amidst these, the mothers of bastard children and prostitutes live without shame and associate freely with the youth, who have also the examples and conversation of the frequent inmates of the county gaol, the poacher, the vagrant, the decayed beggar, and other characters of the worst description. To these may often be added a solitary blind person, one or two idiots and not infrequently are heard among the rest, the incessant raving of some neglected lunatic. In such receptacles the sick poor are often immured. One of the many arguments put forward by the Royal Commission was that these poor houses should be properly regulated and controlled under a new uniform workhouse system. Page 6 Government Response to Poverty The Speenhamland System Another attempt to modify the Elizabethan Poor Law was the Speenhamland System. This idea first saw light of day in 1795. The magistrates in the Berkshire village of Speenhamland introduced it in an effort to relieve the poverty that was caused by the low wages and seasonal nature of agricultural work by topping up workers wages. This system was so popular that it was adopted widely in southern England. It offered any one, or several forms of relief: 1. Wages were supplement or 'topped up' depending upon the size of the family. The amount of relief to be given was calculated on the price of a gallon loaf of bread (weighing 8lb. 7oz.) and the number of children a man had. Some areas allowed between 1/6d and 2/6d per child. This method was later criticised by Malthus who commented that poor labourers had large families so they could claim more relief (benefits) on the poor rates. 2. The Roundsman System, the able-bodied unemployed worked in rotation. They were sent in turn to farmers who paid a part of the wages and the parish paid the rest. In this way the unemployed were put to work. However, some unscrupulous farmers deliberately paid their workers low wages knowing that the local tax payer would top up their wages. The Roundsman System was heavily criticised by the Poor Law Commission for artificially keeping wages low and wasting tax payers money. The Speenhamland system became widespread in southern England and was extensively used in the so-called 'Swing' counties. When the Swing Riots broke out in 1830, some people linked the generous benefits under the Speenhamland System in the south of England with the rioters. Critics of the old system claimed that the Old Poor Law had created an army of unemployed people who depended on benefits who were idle and prepared to break the law. They called for changes to the system to cut taxes and punish the less deserving poor until they found themselves a job. Page 7 Government Response to Poverty Conflicting Views of the Old Poor Law The Speenhamland System was widely adopted during the French Wars. However, it had the unintended effect of increasing the cost of poor relief. In 1815, there was a sharp increase in the numbers of unemployed. Farmers were also struggling as they had got themselves into debt by investing in new machinery and farming techniques to increase production using fewer people. Once the war with France was over, cheap imports from Europe flooded the market and many of them started to go bankrupt. This alongside the increased taxes to pay off the national debt and the cost of local taxes to pay for poor relief started changing attitudes towards the poor. There was a growing belief in the rural south that charity, over and beyond the relief of dire necessity, led to idleness and vice. There was also a belief that allowances and subsidies that had evolved under the Speenhamland System and the Gilbert Act, encouraged people to have large families which in turn increased poverty, unemployment or and crime. These subsides or ‘benefits’ then had to be paid for by rate payers who were unhappy at the constantly increasing cost of the Poor Law. See the chart below: However, in the industrial north, attitudes towards poor relief were different from those to be found in the south. As industry developed, there was a need for workers and if there was work, then most people were employed. If there was no work, then everyone was unemployed. This was particularly true in the textile districts where the anti-Poor Law campaign was at its strongest. It was generally believed that the existing poor relief were more than adequate to meet the needs of the unemployed and others in need of relief. Page 8 Government Response to Poverty Movement for Reform The Swing Riots of 1830 focused attention upon the question of law and order and its relationship to poverty. Amongst the people singled out for attack by the rioters were the parish overseers of the poor relief. One connection made by some politicians at the time was that the worst riots had occurred in places were relief payments were at their highest. It could be argued that it was precisely in these districts that unemployment and social deprivation were at their peak and therefore the cause of the working class or labourers acute desperation that led to the riots in the first place. However, in official circles this coincidence-reinforced dissatisfaction with the existing Poor Law and stereotypes of the causes of poverty and the growing cost of paying poor relief. In 1817 and 1819 national expenditure on poor relief had reached a peak of almost £8 million per year, compared to less than £2 million a year spent from 1783 to 1785. Although the figure then fell back again, the amount spent remained around about £7 million a year. It was felt amongst the propertied classes that the labouring men no longer regarded the receipt of relief as a social stigma. Some argued that the current levels of poor relief undermined their desire or efforts to find themselves a wellpaid job. Page 9 Government Response to Poverty The Royal Commission It was against this background that a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws was appointed in 1832. Many historians have argued that the Royal Commission was prejudiced right from the start, but there is little doubt that the ‘facts’ it presented were accurate. However, the commissioners did ignore data or facts which did not agree with their interpretation of the working of the old Poor Law. For example, at Swallowfield in Berkshire, it was customary to ‘make up’ wages out of the poor rates to what was considered an adequate sum, bearing in mind the price of bread and the size of a man’s family. ‘The bread money is hardly looked upon by the labourers in the light of parish relief,’ the Report declared: ‘They consider it as much their right as he wages they receive from their employers, and in their own minds make a wide distinction between “taking their bread money” and “going on the parish”.’ The ‘bread scale’ policy had been initiated by magistrates meeting at Speenhamland in Berkshire during 1795, as a response to the shape rise in food prices caused with the war with France. This system was soon adopted in a number of adjoining counties and later approved by Parliament. Only in the north of England, where competing employment in manufacturing and mining kept wages high, did such devices prove unnecessary. The problem of with this system was that some unscrupulous employers would deliberately underpay their labourers knowing that they could top up their wages using the poor relief or ‘bread money.’ The deduction made by the Royal Commission was that the Speenhamland system was suppressing wages at the expense of both the local taxpayers and the labourers. Abolishing this system would result in labourers demanding higher wages and a reduced tax burden. Another system investigated by the Royal Commission was the ‘roundsman’ system under which the unemployed were sent from one ratepayer to another until they found someone willing to engage them, at a wage subsidised by the parish. Not surprisingly, the workers concerned took little interest in the tasks they were given as they were paid or given relief whether they performed well or not. For example, at Pollington in Yorkshire: ‘They send many of them upon the highways, but they only work four hours per day; this is because there is not employment sufficient in that way; they sleep more than they work, and if any but the surveyor found them sleeping, they would laugh at them.’ The deduction made by the Royal Commission was that the work being set was inappropriate, encouraged laziness and not cost effective. Page 10 Government Response to Poverty When the commission’s report appeared in 1834, it led to immediate demands for widespread reform. The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act was designed to address the problems of the old system. |A Central Board was to oversee the whole poor law system, while at the local level outdoor relief, save for medical attention, was to be ended for the able-bodied. Instead they were to receive indoor aid only, within a workhouse, with paupers classified and separated according to age and sex and with families divided. The primary objective of the Poor Law of 1834, was to make the paupers’ position ‘less eligible’, that is more unpleasant, than that of any independent labourer and as a result put people off from applying for assistance or help. The Workhouse was to become known as the ‘New Bastilles,’ a place of last resort where the discipline and hard work would encourage none but the truly desperate to willingly enter its gates and seek help. The Poor Law Amendment Act, 1834 The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, embodied the main recommendations of the Royal Commission’s Report and provided for the creation of a national system of poor law administration. At the local level parishes were reorganised into poor law unions with resources sufficient to maintain a well regulated workhouse with elected boards of guardians and paid permanent officials. Each parish remained responsible for the care of its own paupers. Overseeing this system was a central board of three Poor Law Commissioners, guided by Secretary Edwin Chadwick and supported by an inspectorate of assistant commissioners, which sought to impose national standards and practices. The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act led to immediate and visible savings and a rapid fall in the cost of relief in most areas because conditions deliberately were made harsh. The national poor rate expenditure fell from £7 million in 1831 to between £4.5 and £5 million per annum in the decade following its implantation, while for twenty years after that, it fluctuated between £5 and £6 million. However, some of the 'evils' it was designed to destroy were made worse. It started a new administrative structure but probably harmed the relatively defenceless, rather than the idle able-bodied. On the positive side, it limited the power of the local rural tyrant. The changes brought in by the poor law administration saw the rise of the professional administrator at the expense of the local elites. This growing professionalism reduced the role of the landed classes and the magistracy. However, in the long run, indoor relief proved more expensive than outdoor payments and this led to some Poor Law Guardians keeping the old system of 'Outdoor Relief' right up to the start of the 20th Century. Page 11 Government Response to Poverty Opposition to the Poor Law Amendment Act Opposition to the New Poor Law was mixed. The new system was quickly introduced in the south of England, which was mainly agricultural. However, when the Poor Law Commissioners tried to implement the new system in the north there was an explosion of opposition from all sections of society. In the Anti-Poor Law movement was formed in Lancashire and the West Riding, led by Oastler, Fielden (Quaker) and Stephens. The new Poor Law was attacked in the press and on the platform. Richard Oaster, The Rights of the Poor to Liberty and Life What, Sir, is the principle of the New Poor Law? The condition imposed upon Englishmen by the accursed law is, that man shall give up his liberty to save his life. That, before he shall eat a piece of bread he shall go to prison, under circumstances which I shall speak of hereafter, in prison he shall enjoy his right to live, but it shall be at the expense of liberty, without which life itself becomes a burden. 1837 also saw the beginning of a downturn in the economy and poor harvests which began with a trade depression. Industrial workers feared the workhouse, which they called the Poor Law 'Bastilles'. There were riots in Bradford (1837) and Dewsbury (1838). Two failed attempts were made to build work houses in Doncaster which were burnt down. The Poor Law Commissioners had to flee under a hail of bricks and stones. In 1839, Thomas Carlyle a rich land owner wrote: The New Poor Law is an announcement ... that whosoever will not work ought not to live. Can the poor man that is willing to work always find work and live by his work? A man willing but unable to find work is ... the saddest thing under the sun. Another cause of opposition was that the administrators of the old relief system were outraged at the interference of central government or 'London men' in local affairs because they felt the old system worked well. They said that there were few able bodied poor when trade was good, and too many for even the biggest workhouse when trade was bad. The Poor Law Guardians in the north obstructed the implementation of the Poor Law Amendment Act and often refused to build workhouses and often knocked down old houses of correction to prevent the Poor Law Commissioners from ordering their replacement with new workhouses. Page 12 Government Response to Poverty When the Poor Law Commission sent the Assistant Commissioners into northern England to organise the new system, they found themselves faced with a resistance whole organisation and ferocity was unlike anything they had met before. As the source below show, the workhouse system was never fully enforced in industrial Unions in Lancashire and Yorkshire: outdoor relief and supplements to incomes continued. SE Ayling, The Georgian Century, 1714 - 1837, 1966 When the Commissioners went north in 1837 to apply the New Act there, they were met by such a violent and organised hostility that in many areas the principles of 1834 proved impossible to apply, and outdoor relief continued .. its threatened abolition was regarded as a piece of upper class vindictiveness and greed. The proposal to introduce the Poor Law Amendment Act into these areas increased the workers' fears since they might now have to go into the dreaded workhouse in periods of distress rather than receive a small 'dole' from the Poor Law Guardians. Many of the local elites agreed with these fears and could not see the sense in building workhouses big enough to accommodate the thousands of people who would be made unemployed when factories or mines closed due to the ups and downs of international trade. The northern counties not only distrusted the Poor Law Amendment Act but also were well organised to resist it. The Ten Hour Movement of the early 1830s had led to the establishment of a network of Short-time Committees throughout the textile districts of Lancashire and the West Riding and these committees now opposed the implementation of the Poor Law. Local anti-Poor Law committees were set up and their work was co-ordinated by a West Riding anti-Poor Law Committee and a south Lancashire anti-Poor Law Association. Meetings were organised and petitions calling for the repeal of the legislation were sent to Westminster. The leaders of the Ten Hour Movement - Richard Oastler of Fixby near Huddersfield, William Busfeild Ferrand the squire of Bingley, Joseph Rayner Stephens a Non-conformist preacher from Ashton Under Lyne, and John Fielden the cotton manufacturer of Todmorden - now became the leaders of the anti-Poor Law movement. Oastler and his colleagues addressed anti-Poor Law meetings and wrote pamphlets and letters to sympathetic newspapers like the Leeds Intelligencer and the Sheffield Iris in which they denounced the Poor Law Amendment Act as being cruel, unchristian and dictatorial. Most of these speeches and writings Page 13 Government Response to Poverty consisted of highly charged emotional outbursts full of prophetic violence and often of lurid tales of cruelties inflicted on the paupers in workhouses in the south of England. Most of the alleged cruelties were investigated by the Poor Law Commission which found that although some of them were true, many were at best half-truths and others - like the Marcus affair of 1839 - were total fabrications. The anti-Poor Law agitators were determined to portray the Poor Law Commissioners as inhuman tyrants. Emotional speeches and tales of cruelty roused northern workers to fury. In some areas, attempts to put the new system into operation were met with riots. The job of the Assistant Commissioners was made more difficult because many overseers, magistrates and members of the new boards of guardians were determined to obstruct the operation of the new system. In the face of this hostility, the Poor Law Commission was forced to tread carefully and were urged to proceed with caution by Lord John Russell, the Home Secretary, who was alarmed by the amount of violence in the north. Consequently, Boards of Guardians were initially set up to carry out the provisions of the Registration Act of 1836. Even when they were asked to take over poor relief duties from the parishes, the regulations given to them by the Poor Law Commission allowed then to continue to give relief under the old system. Popular resistance to the Poor Law Amendment Act in the north did not survive long. When the workhouse system and its alleged cruelties failed to materialise in northern towns, many working men left the paternalistic anti-Poor Law movement for Chartism, which seemed to have more to offer. Suspicion of the Poor Law Commission did remain strong among many members of Boards of Guardians, however. Having been granted considerable powers of discretion in the performance of their duties, they were determined to defend them against central interference. One Assistant Commissioner noted in 1838, 'The rabble are easily quieted but where a majority of a Board of Guardians is opposed to the Commissioners, the whole proceedings are attended with extreme difficulty.' The new Poor Law was also attacked by many Tories who hated the idea of increasing centralisation of government and the interference in local affairs. Disraeli himself, as a leading member of the ‘Young England’ wing of the Tory party, was a strong opponent of the 1834 legislation, introduced by a Whig government. He condemned the substitution of centralised relief for the old system based on local administration and paternalistic principles. In his novels he painted very critical pictures of leading Whigs who supported the new Poor Law such as Lord Marney and lord Everingham. Many Tories and traditionalist were unsettled by what they saw as the movement away from moral economy to political economy and from relationships regulated by custom to relationships regulated by cash. Page 14 Government Response to Poverty The Andover Workhouse scandal, 1845-6 The Andover scandal of 1845-6 highlighted the hardship of the workhouse regime. McDougal, the Master of the Andover workhouse, had a reputation for inhumanity; rumours of excess cruelty eventually led to a public enquiry. Bone crushing was a normal occupation for paupers. The bones of horses, dogs and other animals (and there were hints that some from local graveyards) were crushed for fertiliser for local farms. The paupers were so hungry that they scrambled for the rotting bones. Bonecrushing became the focus of a case which was reported extensively by The Times and was followed avidly by the public. Edwin Chadwick emerged particularly well and reached the height of his prestige and power at this time. Andover was only the most notorious example of workhouse cruelty. There were several other major scandals and incidents, all recorded by the press in minute detail. Doncaster Workhouse Menu Page 15