“Ellis Island is a reminder of the hope for freedom and prosperity that

advertisement

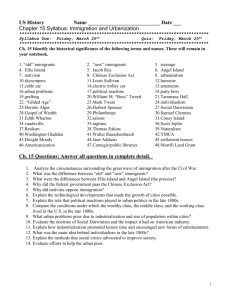

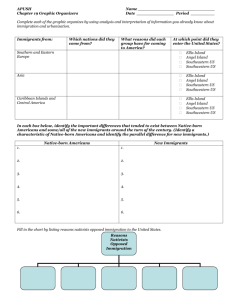

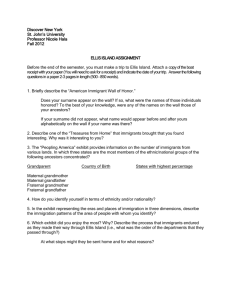

Island of Dreams, Island of Fears: Conflicting Representations of Ellis Island Rebecca Ewing Ewing 2 “Ellis Island is a reminder of the hope for freedom and prosperity that the United States offered to the poor, tired, hungry, and downtrodden of the world,” proclaimed the legislation designating January 1, 1992 as National Ellis Island Day (United States 1991). Congress’ patriotic view of Ellis Island is just one among a host of opinions which have been expressed about the famous island over its century of identity as an immigration facility. From the opening day of the immigration station’s operation on January 1, 1892, through its phases of use and disuse, and finally to its present conception as a National Historic Monument and a museum, the island has been the center of debate over whose meaning should be the official one. Immigrants, historians of immigration, the general public, immigration officials, and the National Park Service have all viewed the island through different colored glasses, some rosier than others. The debates have been especially heated because of the unique nature of the island. Over 12 million immigrants passed through the station during the sixty-odd years it operated, and about 40 percent of all Americans are connected to Ellis Island by an ancestor or relative, giving a broad base of opinions from which to draw praise and criticism (United States 1991). The Ellis Island Immigration Museum, which opened in 1990, is the most recent product of the struggle to give an official meaning to the island and the experiences associated with it. As national opinions change and as new ways of viewing immigration and its effects on society come into vogue, the competition for an official meaning is certainly not yet dead. Although the most significant portion of Ellis Island’s history occurred after the first immigrant station opened in 1897, the island has actually been in use since Colonial times. Under the various names of Bucking, Oyster, and Gibbet Island, through the 1600s and half of the 1700s New Yorkers used the island for various purposes, including oyster catching, oyster 2 Ewing 3 feasts, and state executions (Pitkin 1975). Its present name comes from the last private owner, Samuel Ellis, who owned the island from 1778-1794 and set up a successful tavern and shadand herring fishing business on the three acres exposed above the water (Pousson 1986). The U.S. government subsequently acquired the property and built earthen fortifications to protect New York from the threat of war with France in 1798; a small fort with a twenty-gun battery, Fort Gibson, was finished just in time for the War of 1812 and may have deterred the British from attacking New York. By the 1840s, the Army and Navy shared use of the fort and the circa 1835 gunpowder magazine and did so throughout the Civil War. Not until 1890 did New Jersey congressmen create legislation to remove the magazine, clearing the way for a project to dredge a channel to provide access to the island and build cribworks containing fill to enlarge it. This prepared Ellis Island for construction of the first immigration station, which opened in 1892 (Pousson 1986). The first station operated until 1897, when it burned to the ground, and the present main building was completed in 1900. During the first decade of the 20th century, most of the larger structures on Ellis Island were built, including the hospital complex, contagious disease ward, and psychiatric hospital run by the Marine Hospital Service (later the Public Health Service) (Unrau 1981; Ellis Island 1993). From 1900 to 1914, Ellis Island operated at full capacity processing thousands of immigrants daily; 11,747 travellers entered the record books on one day in April 1907, the most ever processed. This is the classic phase in the island’s history, and our image of the immigrants’ experience comes from this time period. For those who passed through it, Ellis Island held two paradoxical meanings. Some immigrants believed “It was the magic portal of transformation from Europe to America,” (Brownstone, et al 1979), the Golden Door into a land of opportunity and promise. The island 3 Ewing 4 was also the place where people could finally rest after a long journey across the ocean and get a decent meal, families and lovers could reunite after long separations, and job connections could be made for a new start in America. Tied closely to these sentiments, and more present in the minds of the immigrants as they made their way through the main building, was fear. “They shut you up in the ‘Kestlegartel’ [Castle Garden, the previous immigration station, which was often confused with Ellis Island], they take off all your clothes and examine your eyes,” went a typical story at home in Europe. “If your eyes are healthy, it’s all right. If they aren’t, they make you go back to where you came from” (Sholom Aleichem quoted in Perec and Bober 1995: 22). Every immigrant had to pass a two minute medical exam in order to be admitted, and while only two percent were ever turned away, all dreaded the possibility of being detained or sent home (Perec and Bober 1995). The physical environment in which the medical examinations took place was intimidating, as well. Before 1911, the floor of the Great Hall where most of the examination process took place contained bars to keep lines orderly and wire mesh cages to separate immigrants who did not pass the initial health inspection. To many, the bars and cages resembled cattle pens and stalls, and the uniformed Public Health Service officials looked for all the world like soldiers (Brownstone et al 1979). Combined with the swift medical exam, the overtaxed nerves of the U.S. Immigration Department workers, and the disorientation of being ordered around in and surrounded by a cacophony of languages, it is easy to imagine how frightening a place Ellis Island could be. The island symbolizes much of the controversy which surrounded immigration laws from the 1920s through the 1950s. The First and Second Quota Laws, enacted in 1921 and 1924 respectively, sharply restricted the number of immigrants allowed to enter from each country, favored emigrants from northern European rather than southern European countries, and 4 Ewing 5 provided for examination at overseas consulates. After the laws were enacted, Ellis Island’s role changed dramatically; it became a detention center for new immigrants with problematic paperwork or questionable health and a point of deportation for aliens who entered the U.S. illegally or violated the terms of their admission (Unrau 1981; Novotny 1971). During both World Wars, the government used hospitals and dormitories on the island as detention centers for suspected enemy aliens, especially those of German, Italian, and Japanese (WWII) descent. Edward Corsi, commissioner during the early 1930s saw the deportation and detention programs as a “weeding out of ugly and sick elements in our national life,” a sentiment which the government and many Americans shared (quoted in Tifft 1990: 124). The Golden Door was not completely closed, however, for the 1948 Displaced Persons Act allowed extra numbers of immigrants to enter, opening America’s shores to refugees with no homes after WWII. For many of those same people, the door wildly swung shut again in 1952 with the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act which rigidified the quota system and barred all aliens who had been or were members of totalitarian, and especially Communist, organizations (Novotny 1971; Tifft 1990). Once again, Ellis Island became a sad place of travellers marooned on their way to new lives and people puzzled by bureaucracy. By 1954, numbers of people entering Ellis Island had dropped so low and the buildings were in such poor shape that officials decided the facilities had finally run their course of usefulness. Accordingly, the remaining immigrants were released on parole or transferred to the Immigration Services offices in New York, and on November 12, 1954, the last immigrant left, the last official locked the door behind him, and the gateway which had stood open for sixty years closed forever (Novotny 1971; Pitkin 1975). The U.S. Immigration Service no longer needed Ellis Island, and in March 1955 the 5 Ewing 6 General Services Administration (GSA) declared it to be “surplus to the needs of the federal government” (Unrau 1981:86), setting into motion a twenty year debate about what to do with the island. First, the GSA attempted to sell the property, offering it to New Jersey, New York, and private interests. Many proposals for public projects came in, but ultimately the GSA rejected them all because of inadequate funding. Next, the island was offered for commercial development as a prime site for an “oil storage depot, import and export processing, warehousing, manufacturing,” and other similar activities (Blumberg 1982: 96). Millions of protest letters were sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and other officials connected with the island expressing such sentiments as, “To millions and millions of Americans Ellis Island was the 19th and 20th century counterpart of Plymouth Rock,” and suggesting that the island be turned into a shrine to all the immigrants who passed through the facilities (anonymous letter quoted in Blumberg 1982: 97). The GSA once again offered the island for sale in 1958, because no definite decisions had been made, but once again, such an outcry from government and public officials arose that Congress decided to study further options. In 1964, the National Park Service (NPS) issued a study declaring “permanent recognition of the national historical importance of Ellis Island should have first place in plans for its future use” and it should be placed under the auspices of the NPS (Novotny 1971: 141). President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law Proclamation 3656 on May 11, 1965, adding the island to Statue of Liberty National Monument under the direction of the National Park Service. He also took advantage of the signing ceremony’s theme to make a political call for passage of his immigration reform bill, which loosened the quotas set in place in the 1920s, as well as to approve a new Job Corps Conservation Center on the New Jersey shore near the island to help in the restoration work (Blumberg 1982; Pitkin 1975; Novotny 1971). 6 Ewing 7 Actually implementing plans to create a national monument and museum on Ellis Island proved to be much more difficult than simply signing a proclamation. The NPS agreed that an immigration museum somewhere in the Port of New York would be appropriate, since in the opinion of William H. Baldwin, a trustee of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, “the cold war with the Soviet Union had produced a need for national unity, . . . and such a museum would be a strong force to this end” (Pitkin 1975: 181). The NPS was divided on where the museum should be placed. At that time, a fund-raising campaign for an American Museum of Immigration (AMI) planned for the base of the Statue of Liberty was in the works. Officials with the campaign saw plans for a similarly themed museum on Ellis Island as a grave threat to their own museum and fund-raising campaign, and the co-chairmen issued a joint statement to the New York Times proclaiming, “It is inconceivable to us that [Ellis Island] should be considered as appropriate for a national tribute to immigration. . . . No immigrant was ever attracted to America by Ellis Island. . . . The lodestar for all of them was the Statue of Liberty. . . . Liberty Island is a happy place of continuing inspiration, not a depository of bad memories” (David J. McDonald and Pierre S. duPont III quoted in Blumberg 1982: 97-98). Putting the monetary needs of the museum before concerns of practicality (the space in the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal is quite limited), and not even bothering to consider what immigrants themselves might think about where to create a museum, AMI officials ultimately created a museum which inadequately represented immigration and presented it with the outdated view of a unified American society, ignoring the cultural pluralism that more realistically exists (Holland 1993). Despite public interests and attempts to get money appropriated from Congress for Ellis Island’s upkeep, the Vietnam War interrupted plans, and no one paid much attention to the 7 Ewing 8 island. The buildings languished, falling literally into disrepair, since the National Park Service had a pitifully small amount of funding with which to heat or care for any of the buildings. Ceiling plaster fell, paint flaked, vegetation grew to jungle-like conditions, curtains rotted off rods, machinery and furniture rusted in place and collapsed. The roof leaked, pipes burst, windows broke in, and vandals stole valuable copper from the cupolas (Benton 1985; Tifft 1990). The NPS created a Master Plan for use of the island, presenting a development concept that included interpretation for visitors focused on the examination process in the baggage room and main hall, exhibits of information on immigration in general, and a park for ethnic group activities which reflected immigrants’ cultural origins (United States 1968). Despite having the plan and the public’s support for a museum on Ellis Island, Congress still appropriated no money, and the island sat vacant and decaying for another ten years (Tifft 1990). No attempt to create a meaningful monument to the immigrants occurred until a determined citizen, Dr. Paul Sammartino, lobbied Congress to finally pay out money authorized in 1965 for use in rehabilitating the island in time for the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations. Because so little money ($1 million for repairs and $500,000 to the NPS for running the site) was finally appropriated, the island which opened to the public in May 1976 was a sad form of its earlier self. As a reporter from the New York Times described the main building, which was the only one open, This one had been shored up and rendered safe, but it is moldering. Interior walls have crumbled. Mounds of fallen plaster and pools of rainwater from leaking roofs spread darkly across some of the floors. Dust and peeling paint are the most benign signs of the slow rot. Windows are out, and in one room moss and small trees are growing, and pigeons have settled in. Here and there bits of salvaged old furniture have been arranged forlornly in an attempt to recapture the era (Sidney H. Schanberg quoted in Tifft 1990:171-172). What the NPS ultimately presented to the public was the image of an immigrant heritage about which the government cared very little. Its forlorn appearance, which was supposed to 8 Ewing 9 evoke the sense of immigrants arriving during the first two decades of the 20th century, instead elicited puzzled sorrow. French filmmaker Georges Perec (1995) recorded, “what I find present here / are in no way landmarks or roots or / relics / but their opposite: something shapeless, on the outer edge of / what is sayable, / something that might be called closure, or cleavage, / or severance.” Polls conducted during these tours in the late 1970s indicated the majority of visitors wanted to see the island partially or fully restored (Blumberg 1982)—once again, the government and the people had two very disparate meanings that neither side could manage to combine into one. The final and most recent phase in Ellis Island’s history was marked by the Department of the Interior’s decision to organize a commission to head all the private groups wanting to lead fundraising efforts for the island. President Reagan chose Lee Iacocca to be head of the Centennial Commission and later the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. As the son of immigrant parents who had passed through the island, a man who had climbed the ladder of American success, and a prominent businessman who had recently rescued a floundering Chrysler Corporation, he was the perfect person to raise money effectively (Holland 1993). Appointing Iacocca was a calculated move for Reagan, since it not only upheld and further romanticized the “American dream,” but also was to prove “how much more effectively private enterprise and fund raising could accomplish a historic restoration than a government bureaucracy like the National Park Service” (Bodnar 1995: 18). The Ellis Island Immigration Museum, which opened its doors in 1990 after nearly forty years in formation, reflects a complicated set of ideals from the perspectives of both of the new social historians and the Reagan administration, a combination which does not always work. The museum has nine exhibit areas which tell the story of immigration through general facts and 9 Ewing 10 the specific case of Ellis Island. Although the NPS has no designated path to follow, the one favored most by park rangers and outside professionals follows the route immigrants took and begins in the old Baggage Room and proceeds up a restored stairway to the Registry Room, or Great Hall. After that, visitors are free to see the exhibits “Through America’s Gate,” which gives step-by-step details of the processing procedure; “Peak Immigration Years: 1880-1924,” about the origins of immigration and immigrants’ lives in the U.S.; “Ellis Island Chronicles,” an overview of the island’s history to 1954; “Silent Voices,” which pictorially documents the process of abandonment and restoration; “Treasures from Home,” a display of artifacts immigrants brought with them from their homes; “The Peopling of America,” situating Ellis Island’s role in the broader context of global immigration; and the memorial American Immigrant Wall of Honor, which lists the names of over 500,000 immigrants whose progeny made a minimum donation of $100 to the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation (Tifft 1990; Smith 1992; Wallace 1991; Yans-McLaughlin and Lightman 1997). While the exhibits and displays do give a broad overview of immigration, present a full picture of the immigration process before, during, and after Ellis Island, and deal specifically with the facilities on Ellis Island, the official meanings intended by the creators do not always transfer well to the public’s interpretation. For instance, according to Ellis Island and the Peopling of America: The Official Guide, the interpretive plan for the museum documents the island’s function as an immigration station. A major exhibit is “The Peopling of America,” which “contextualizes [the immigrant processing] story by documenting immigration to the United States from all the world’s continents including Africa, Asia, and South America over the course of American history” (Yans-McLaughlin and Lightman 1997: 78). However, most visitors concentrate on the Great Hall and the exhibits which more directly pertain to 10 Ewing 11 immigration as they see it than “The Peopling of America’s” colorful graphics and bountiful statistics (Wallace 1991; Smith 1992). The same guide says a popular exhibit is the American Immigrant Wall of Honor, but for early visitors to the museum, “Treasures from Home” seemed to be the favorite exhibit, and Smith’s (1992) and Wallace’s (1991) scholarly reviews of the museum ignore it completely (Yans-McLaughlin and Lightman 1997). Overall, the exhibits on display present a progressive process through which such people as Irish, Italians, Germans, Hispanics, Chinese, and South Africans became Americans (Bodnar 1995). Exhibit themes such as “Through America’s Gate” and “The Peopling of America” reinforce this impression, which ties into the larger image America has frequently promoted of itself as a nation ever moving forwards and upwards (Bodnar 1987). Yet, the exhibits contradict themselves. Displays in “The Peopling of America” such as a globe displaying major migration pathways since 1700 (Wallace 1991), which are meant to emphasize the multicultural nature of the U.S., could easily become a way to trace only one family’s or country’s emigrants and ignore those from other places. “Treasures from Home” could just as easily reinforce pride in a visitor’s ancestors and the home country as prompt one to think about why the immigrants chose to bring the artifacts they did. The new social history, at work in so many of the exhibits, does not extend to all of them, and there are a few glaring gaps in the immigration story being told. Those gaps are ones that historians more than the general public would be likely to notice, but they are vital to a complete story, even more so because few laymen are aware information is missing. From the exhibits in the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, one would little guess many unsavory characters came through the gate. Gangsters and criminals are not mentioned, although they surely came; prostitutes concerned immigration officials, as well, as attested by strict early 20th century rules mandating that no single female could be accompanied off the island by a male (Wallace 1991). 11 Ewing 12 From the descriptions of exhibits given (i.e. Bodnar 1995; Smith 1992; Wallace 1991; YansMcLaughlin and Lightman 1997), psychiatric patients receive little attention as well, even though a specific hospital facility was built to house them. And most glaringly absent from the story presented in the museum is the deportation center phase, half the lifetime Ellis Island saw in immigration service. As a visible and physical witness to changing U.S. immigration policy and public attitudes, the museum should acknowledge the island’s role in directing the flow of immigrants in both directions over the Atlantic. If the museum directors and curators are willing to display an exhibit on America’s adverse reactions to immigrants, they should certainly be willing to offer a complete history of the island and of U.S. immigration policies to visitors. Ellis Island’s symbolism over the years can be seen through a number of diametrically opposed relationships. One of them is the conflict between immigrants and officials working on the island. Many officials probably saw their jobs as part of a bureaucratic routine and a necessary step in the process of being admitted into America. The immigrants, however, had a much more personal reaction to the process, finding the experience both hope-inspiring and sadness-provoking. Two other antagonists in the argument about its meaning have been those who used the island and those who funded the island. After the great need for large facilities passed with the signing of the First and Second Quota Laws and the McCarren-Walter Act, officials on the island had to struggle with Congress to find enough money to fix buildings and implement programs to make detained immigrants’ stays more comfortable. The public and Congress have had their share of run-ins, as well, witnessed by the GSA’s repeated attempts to sell Ellis Island for commercial development despite huge outpourings of public sentiments to the contrary. Even the public has been divided over the course of the 20th century. At the beginning of the century, Americans saw Ellis Island as the source of many evils entering 12 Ewing 13 society—drinking, gambling, prostitutes, anarchists, and the like (Novotny 1971). Now, however, when over 40 percent of Americans can trace their heritage to someone who came through Ellis Island, “it represents the hopes and aspirations of all people who came—and are still coming—to this country in search of the American Dream,” as Lee Iacocca summed up the symbolism (Foreword in Tifft 1990: xii). Historians, in many instances the creators of history just as much as those who actually participated in historic events, have been at odds with each other over how to present immigration. The fierce arguments which arose around the American Museum of Immigration at the base of the Statue of Liberty stemmed partly from disparate opinions of which symbol could best represent immigration. Those with the AMI felt the Statue of Liberty’s welcoming message of hope, freedom, and liberty was the most appropriate one to support their image of a unified American society. New social historians working on Ellis Island argued from a much broader perspective and emphasized America’s culturally pluralistic nature, where many elements of all different backgrounds are mixed together but remain separate entities (Holland 1993). Throughout its long and intricate history, Ellis Island has been a place of symbols and a source of conflicting meanings. Because so much of the island’s history is intensely personal and emotional, the symbols associated with it become that much more volatile. From the wooden halls the first immigrant passed through in 1892, to the crowded rooms of the 1910s, to the almost empty island of the enemy aliens of the 1950s, to the abandoned hulk of a building in the 1970’s, to the Great Hall’s restored splendor of the 1990s, Ellis Island has represented far more than simply a place where some 12 million people entered the United States or where 2% were returned to their homelands (Perec and Bober 1995). It has stood as a gauge for Americans of how welcoming their shores really were. How ironic that the island which was seen for so 13 Ewing 14 many years as a place of fears and tears is now associated with the Statue of Liberty, the universal symbol of America’s freedom and brotherhood with all nations and all peoples. While historians have struggled with exhibits at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum to present the many facets of immigration, the old notions the public has about emigrants and the reasons why they came have changed little. One could question the effectiveness of the new social history at elucidating the complexities of immigration in a museum setting, but what might be more illuminating is to examine members of society. They are the ones who must ultimately accept or reject historians’ new ideas, and, because they want to believe it or because for some of them it was true, the public insists on holding fast to the romantic notion of immigration as a search for freedom and liberty. As historians develop new ways of viewing America’s history, as those who actually passed through Ellis Island become fewer in number, and as Ellis Island fades to the back of Americans’ memories, the debates over Ellis Island’s symbolism will surely continue. Ellis Island’s restored main building has not seen the end of conflicting hopes and frustrated tears, nor will it for many years to come. 14 Ewing 15 BIBLIOGRAPHY ----1993 Ellis Island: America’s immigration cornerstone. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Washington D.C. ----1997 Doctors at the Gate: the U.S. Public Health Service at Ellis Island. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Washington, D.C. Benton, Barbara 1985 Ellis Island: A Pictorial History. Facts On File Publications, New York. Bodnar, John 1986 Symbols and Servants: Immigrant America and the Limits of Public History. Journal of American History 73:137-151. 1995 Remembering the Immigrant Experience in American Culture. Journal of American Ethnic History 15:3-27. Blumberg, Barbara 1985 Celebrating the Immigrant: An Administrative History of the Statue of Liberty National Monument 1952-1982. Division of Cultural Resources, North Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Brownstone, David M., et al 1979 Island of Hope, Island of Tears. Rawson, Wade Publishers, New York. Holland, F. Ross 1993 Idealists, Scoundrels, and the Lady: an insider’s view of the Statue of LibertyEllis Island project. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. Novotny, Ann 1971 Strangers at the Door: Ellis Island, Castle Garden, and the Great Migration to America. The Chatham Press, Riverside, Connecticut. Perec, Georges with Robert Bober 1995 Ellis Island. Translated by Harry Mathews and Jessica Blatt. The New Press, New York. Pitkin, Thomas M 1975 Keepers of the Gate: A History of Ellis Island. New York University Press, New York. 15 Ewing 16 Pousson, John H 1986 An overview and assessment of archaeological resources on Ellis Island, Statue of Liberty Monument, New York. Eastern Team, Denver Service Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Smith, Judith 1992 Celebrating Immigration History at Ellis Island. American Quarterly 44:82-100. Tifft, Wilton S 1990 Ellis Island. Contemporary Books, Chicago. United States 1968 A Master Plan for Ellis Island, New York. National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 1992 Joint Resolution Designating January 1, 1992 as “National Ellis Island Day.” U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. Unrau, Harlan D 1981 Historic Structure Report, Ellis Island, Historical Data, Statue of Liberty National Monument, New York/New Jersey. Denver Service Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. 1984 Historic Resource Study, Ellis Island, Statue of Liberty National Monument, New York-New Jersey. Vol. 1. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington, D.C. Wallace, Mike 1991 Exhibition Review. The Journal of American History 78:1023-1032. Yans-McLaughlin and Marjorie Lightman 1996 Ellis Island and the Peopling of America: The Official Guide. The New Press, New York. 16