ucla department of english

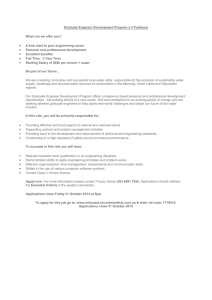

advertisement