RNA Banks Supple entry 2011

advertisement

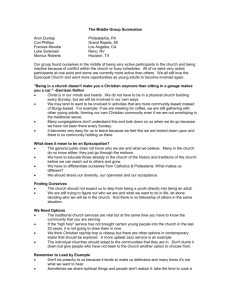

RNA Banks Supple entry 2011 June 29, 2010 Churches torn on whether to allow molesters in pews | By Adelle M. Banks (RNS) “All are welcome” is a common phrase on many a church sign and website. But what happens when a convicted sex offender takes those words literally? Church officials and legal advocates are grappling with how—and if—people who’ve been convicted of sex crimes should be included in U.S. congregations, especially when children are present: -- Last week (June 23), a lawyer argued in the New Hampshire Supreme Court for a convicted sex offender who wants to attend a Jehovah’s Witnesses congregation with a chaperone. “What we argued is that the right to worship is a fundamental right, and the state can only burden it if it has compelling interest to do so, and then only in a way that is narrowly constructed,” said Barbara Keshen, an attorney with the New Hampshire Civil Liberties Union who represented Jonathan Perfetto, who pleaded guilty in 2002 to 61 counts of possessing child pornography. -- On Monday (June 28), the Seventh-day Adventist Church added language to its manual saying that sexual abuse perpetrators can be restored to membership only if they do not have unsupervised contact with children and are not “in a position that would encourage vulnerable individuals to trust them implicitly.” Garrett Caldwell, a spokesman for the denomination, said the new wording in the global guidelines tries to strike a balance between protecting congregants and supporting the religious freedom of abusers in “a manifestation of God’s grace.” -- On Thursday (July 1), a Georgia law will take effect that permits convicted sex offenders to volunteer in churches if they are isolated from children. Permitted activities include singing in the choir and taking part in Bible studies and bake sales. The Rev. Madison Shockley, pastor of Pilgrim United Church of Christ in Carlsbad, Calif., whose church publicly grappled with whether to accept a convicted sex offender three years ago, said he hears from churches several times a month seeking advice on how to handle such situations. “The key lesson for churches is this: The policy, however it winds up, must be a consensus of the congregation,” Shockley said. “I talked to so many pastors who decided they’re going to make the decision because they know what’s theologically and spiritually right—and that’s absolutely the wrong thing to do.” Shockley’s church will soon commission a minister to address prevention of child sex abuse; the church also distributes a 20-page policy on protecting children and dealing with sex offenders. Shockley declined to say how the church handled its admission of a known abuser in 2007, citing the congregation’s limited disclosure policy. Beyond the thorny legal questions, theologians also find that there are often no easy answers to the quandary of protecting children and providing worship to saints and sinners alike. “My own theology of forgiveness is not that it’s a blanket statement—`You are forgiven; go and sin no more,”’ said Rev. Joretta Marshall, professor of pastoral theology at Texas Christian University’s Brite Divinity School. “Part of what we have to do is create accountability structures because damage has been done.” Sometimes, legal and religious experts say, crimes are so severe that convicted offenders must lose their right to worship. New Hampshire Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Cort argued in court documents that Perfetto should not be permitted to change the conditions of his probation to attend a Manchester congregation because “restricting the defendant’s access to minors was an appropriate means of advancing the goals of probation—rehabilitation and public safety.” Barbara Dorris, outreach director of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), said it may be possible for convicted offenders to attend worship if “proper safeguards are in place,” but offenders “forfeit many rights when you commit this kind of a felony.” In other cases, the wording of laws has made it difficult for offenders who want to worship to be able to attend church legally. In North Carolina, attorney Glenn Gerding is representing James Nichols, a convicted sex offender who is contesting a state statute that made it illegal for him to be within 300 feet of a church’s nursery. He was arrested in a church parking lot after a service. “Technically a person could go to an empty church and violate the statute if that church has a nursery,” said Gerding, whose client was convicted in 2003 of attempted seconddegree rape and released from prison in 2008. In Georgia, the Atlanta-based Southern Center for Human Rights successfully argued for the removal of a legal provision that would have prevented registered sex offenders from volunteering at church functions, said Sara Totonchi, executive director of the center. Experts say churches need to abide by state laws and be prepared to handle the possible presence of sex offenders, which could mean ministering to them outside the church building. Steve Vann, co-founder of Keeping Kids Safe Ministries in Ashland City, Tenn., said children’s safety must be paramount, but giving convicted abusers social support could help reduce additional offenses. “We talk about covenant partners,” he said, using his ministry’s phrase for chaperones. “They’re not just there to watch what the person does. They’re there to assist the person in spiritual growth.” Andrew J. Schmutzer, a professor at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, is editing a book called “The Long Journey Home,” which includes essays from theologians and ethicists about how churches can both address sexual abuse and predators. “The churches are on the cusp of trying to figure out what they can do,” he said, “without scaring the public and without breach of confidentiality.” -30- October 13, 2010 After teen suicides, gay opponents look inward By Adelle M. Banks (RNS) When Rutgers University freshman Tyler Clementi killed himself after his roommate allegedly broadcast his sexual encounter with another man, the Rev. R. Albert Mohler wondered if anything could have prevented the 18-year-old’s suicide. “Tyler could just have well been one of our own children,” said Mohler, a father of two and president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, who criticized the Christian treatment of gays on his blog. “Christians have got to stop talking about people struggling with sexual issues as a tribe apart.” In the wake of a spate of gay youths who were bullied—and some who took their own lives—Mohler and some other vocal opponents of homosexuality are taking new steps of introspection. While defending traditional Christian teaching against homosexuality, they say divisive and condemnatory rhetoric needs to be replaced with actually getting to know a gay neighbor or classmate. Some have gone even further. Exodus International, a leading “ex-gay” group, pulled its sponsorship of the annual “Day of Truth,” which encourages students to express their disapproval of homosexuality. Alan Chambers, president of Exodus, recalled the pain of being a middle schooler who was bullied because peers thought he was gay. The recent suicides led him to think his organization needed to lead the way in encouraging less “polar” ways of addressing sexuality. “I think the church really needs to approach these issues in a much more conversational, relational, service sort of way,” Chambers said. “Not to change our position about biblical truth—because we haven’t done that—but to really understand that whether someone agrees with us on this issue or not doesn’t mean that they’re not our neighbor.” On Tuesday (Oct. 12), Mormon officials received 150,000 signatures on a petition that criticized a top church leader for condemning gay marriage and declaring that a homosexual orientation can and should be changed. Noting Mormons’ own history of persecution, church spokesman Michael Otterson said there is “common ground” between Mormons and gay rights supporters on the topic of standing against bullying and harassing young gays. “Our parents, young adults, teens and children should therefore, of all people, be especially sensitive to the vulnerable in society and be willing to speak out against bullying or intimidation whenever it occurs, including unkindness toward those who are attracted to others of the same sex,” he said. The current issue of an Assemblies of God ministers’ journal discusses pastoral counseling on homosexuality, and while the church maintains that homosexual behavior is “against God’s word,” leaders say hatred and bullying are entirely inappropriate. “It’s that balance between conviction and compassion and we are really trying to walk a line,” said the Rev. James Bradford, general secretary of the Pentecostal denomination. Gay rights groups, meanwhile, remain skeptical. Such sentiments are a positive “step in the right direction,” said the Rev. Rebecca Voelkel of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, but they do not go far enough. “If we reach out in love, and yet our real message is that who you are as a lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender person is not beloved in the sight of God, then that reaching out may in fact be under false pretenses and could in fact be even more dangerous,” said Voelkel, a minister of the United Church of Christ. In recent weeks, blogger John Shore has found many evangelicals grappling with these issues in their comments on his blog post that connected Christian opposition to homosexuality with gay teen suicide. Shore, a progressive Episcopalian from San Diego, said he can’t applaud evangelicals who say they are sympathetic to gays but also condemn their behavior as sinful. “It doesn’t matter during the course of the day how often I move to defend the gays if at the end of the day I am convinced that the way they are is an abomination to God,” he said. Pastor Mike Cosper of Louisville, Ky., said he agrees with Mohler that the church could be less judgmental about homosexuality, and believes evangelicals shouldn’t get any more “fired up” about it than they would about greed or any other sin. Yet he disagrees with advocates like Voelkel who wish conservative churches would change their viewpoint on sin. “The reality is we have historic faith, we have a belief and we have plenty of anecdotal and testimonial evidence of people who’ve said I’ve walked away from this lifestyle,” said Cosper, whose Sojourn Community Church has hosted conferences to help pastors “shepherd people through that journey.” Religious leaders aren’t ready to lay the blame of the suicidal deaths of gay teens like Clementi on themselves. But Mohler said gay friends in his congregation have helped him realize he should not consider homosexuality “someone else’s problem.” “Do I think the church is primarily to blame? No,” said Mohler. “But does the church have a responsibility? You bet. ... I’m not suggesting there was some congregation that failed (Clementi). My concern is that we’re failing many others.” -30- November 25, 2010 Play examines South’s black church arsons By Adelle M. Banks WASHINGTON (RNS) For playwright Marcus Gardley, the theater is his pulpit and plays are his sermons. His latest production, “every tongue confess,” seeks answers to the questions that swirled around the spate of arsons that hit black churches in the South in the 1990s. “How deep does your forgiveness go?” Gardley asks in an interview. “Do you have the capacity to forgive someone even if they burn down the church?” As a high school senior, Gardley, now 32, would rush home to check the latest news on the fires between reports on the O.J. Simpson murder trial. “That decade, 300 churches burned in the South—300,” he said. “I thought, well, why is that not getting at least the amount of coverage or more? They haven’t found the people that are burning these churches. Why is this not considered a big deal?” Actress Phylicia Rashad, best known for her role as the smart and savvy Clair Huxtable on “The Cosby Show,” portrays Mother Sister, the preacher of a Baptist church in Boligee, Ala., whose members fear the next arson could hit them. Her character echoes Gardley’s sentiments as the church faces the fires that burn around and within them. “Three hundred churches have burned in the last 10 years and the government ain’t done nothin’ but turned its back,” Mother Sister preaches. “They can’t see that our church is all we got. It’s where we baptize our babies, marry our young’ins, bury our dead. It’s where we embrace God.” The play, commissioned by Washington’s Arena Stage, premiered Nov. 9 and is scheduled to run through Jan. 2. Rashad called the play “epic” in its treatment of broad themes of recognition and forgiveness that transcend beyond the arsons that shook the South a decade and a half ago. “The church burnings, yes, that’s a very big part of it but it’s more about what’s going on in people that leads to church burning,” she said in an interview. “How is it that you profess love for God but can’t accept another human being?” As he researched the fires, Gardley was struck by the news accounts of Timothy Welch, a member of the Ku Klux Klan who was convicted of burning two churches. Years earlier, he had sat outside a church he later torched, listening to the service inside. “He didn’t realize he had community all along,” said Gardley, who believed the church should have been his community instead of the Klan. The playbill includes a note of forgiveness from a burned church’s pastor to Welch. Rashad and Gardley compared the outreach to rebuild the churches, which spanned racial and regional lines, to the play’s message about discovering how people are more alike than they are different. “I felt like the big message of the play is these are all our churches,” said Gardley, the son and nephew of ministers who was raised in the Church of God in Christ and now attends Times Square Church at the heart of Broadway. Rashad, who was christened an Episcopalian and now says she has “great faith in God and in God’s presence in all things,” said the play aims to build human, not just racial understanding. “I think the real understanding comes when we recognize our humanity in each other,” she said. “That’s not just between blacks and whites. That’s between all religions as well.” Clocking in at just under two hours, “every tongue confess” captures the ethos of the black church, with recordings of gospel artist Shirley Caesar, a tambourine-playing black woman and a white female soloist who comforts Rashad’s character with a stirring rendition of “His Eye is on the Sparrow.” Humor slips in as the characters remark on the summer heat—“hotter than a hooker house on nickel night”—and the playbill’s church bulletin cautions against mayonnaise in potluck dishes. As his characters struggle with interracial relationships, lynchings and dreams of a better life in the big city, Gardley demonstrates how interconnected they all are. Their names invoke both the church and the fires around them: Gossiping church members are called Brother and Elder. Mother Sister’s son Shadrack, and Benny Pride, the daughter of an arsonist, are plays on the names of Shadrach and Abednego, two of the three men who survived the fiery furnace in the Old Testament book of Daniel. As the title implies, every character has a confession to make. And as the fires grow, they do. “Looks like we ain’t got much time left,” says Elder. “Should I pray? Should I sing a hymn from back in the day? Should I gossip?” Gardley said the play was shaped by his experience as a teenager attending a Foursquare Gospel church in Oakland, Calif., where the words of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. hit home. “What I learned at the church is more about the power of diversity,” he said, “and about what it really means to accept people for the content of their character.” -30-