Fulbright & Jaworski Document

advertisement

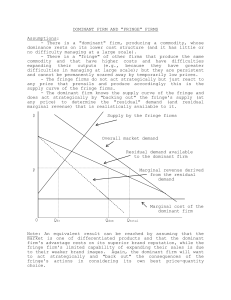

Brandon Todd HIST 6393, Spring 2007 Karger, Howard. Shortchanged: Life and Debt in the Fringe Economy. San Francisco: BerrettKoehler Publishers, Inc, 2005. With Shortchanged, Howard Karger has painted a compelling portrait of life in the fringe economy. For people who live at or below the poverty line, or people who fall dangerously into debt or have bad or no credit, life in the fringe is a nearly inescapable trap of high interest rates and predatory lenders. Shortchanged analyzes in detail the many various financial pitfalls of the fringe and in general gives the reader and overall feeling of despair with regards to the unfortunate families forced to live under these conditions. Karger describes the “fringe economy” as “corporations or business practices that have a predatory relationship with the poor by charging excessive interest rates or fees, or exorbitant prices for goods or services.” For most of the people forced to deal with the fringe economy, they do so because it is the only option. Most have bad or no credit and insufficient funds to start a bank account and pay bank fees. With traditional banking services closed off, that leaves only lenders willing to give our high-risk loans at a high interest rate. On the surface, higher interest rates for higher risk loans makes perfect logical sense. After all, lenders have to protect themselves in the eventuality of a default. However, as Karger discovers, on the fringe economy, interest rates often exceed by several times the rate necessary given the risk. Over the course of several chapters, Karger examines the more common fringe servicespayday advance loans, check cashing services, pawn shops, subprime mortgage lenders, used car lots, etc. Throughout all these various businesses, a common thread connecting them all is the lender’s desire to string the payments along for as long as possible. Paying off the principle of a loan is the last thing that any of these businesses want. Credit Card Issuers (CCIs) come Todd-Karger.doc -1- immediately to mind as an example of this type of practice. CCIs, usually a bank (not VISA, et al), issue a line of credit to the customer, with payment being due at a set time each month. However, the payment that is due is a minimum monthly payment, not the full amount of charges up to a person’s credit limit. The CCI then charges interest on the balance based on a set rate, sometimes as high as 20%-30% for customers with bad credit scores. Karger argues that in an ideal situation, the customer would only make a monthly payment large enough to pay off the interest earned on the balance, thus multiplying the total amount paid many times over. If a customer pays off the monthly balance completely each month, the worst kind of customer for a CCI, the CCI will often begin charging annual fees to make at least some money off of the customer. This type of lending practice, offering minimum payments well below the amount owed and charging extremely high rates on the balance, is common among all fringe lending businesses. Another common theme discovered by Karger involves the idea of high interest rates for high-risk loans. Nearly all lending organizations charge a higher rate on a loan that is, in there opinion, less likely to be paid off. If the borrower defaults on the loan, the lender will have collected more interest on the portion of the loan that was paid off, thus decreasing their losses. However, Karger argues that fees and interest rates in the fringe economy wildly exceed those normally expected for the given risk. The most glaring example comes in the form of pawn shops. Pawn brokers collect collateral in the form of household items-appliances, jewelry, etc.in exchange for a loan. Along with the loan, the borrower is given a pawn ticket for their item. After a month, the borrower either pays back the loan and redeems the pawn ticket for their item or pays a fee to extend the loan term. If neither of these options are exercised, then the item goes on sale in the pawn shop, at a price greater than the loan amount. The fees associated with pawn Todd-Karger.doc -2- shop loans, $150 monthly fee on a $1000 loan for example, can range anywhere from 150% to over 300% APR (annual percentage rate) in most cases. These rates are clearly predatory and greatly exceed the reasonable amount for a high risk loan. Compounding this, argues Karger, is the fact that pawn shop loans are in fact very low risk. Studies show that over 70% of borrowers return to collect their items, with most extending their payments with monthly fees. Fees collected from this 70% more than make up for the 30% who abandon their items. Moreover, those items that are abandoned are sold for prices greater than the amount of the loan they purchased—pawn shops traditionally appraise items for less than 50% of their value. The risk for pawn shops then is virtually zero. Nearly all businesses in the fringe economy justify their predatory rates as the cost of doing business with high-risk customers, when in fact the reality of the situation is that many of these business face no more risk than traditional lending organizations. In fact, Karger reports that financial reports issued by the corporations behind these fringe shops report losses of less than 1% each year. There is no doubt regarding the situation in Karger’s opinion—fringe lending is all reward and very little risk. At the end of each chapter discussing the various types of fringe lending, Karger offers thoughts on how the situation can be improved. In general, Karger believes that the all fringe business should be more closely regulated. However, he also knows that the corporate power behind these businesses will always be able to find a legal loophole around regulations. For instance, in 1979 the Supreme Court ruled that national banks could charge interest rates at the highest rate allowed by their home state. Banks rushed to move their official home to the states with the highest rates, allowing them to bypass the lower limits approved by the other states. The only way to truly solve the problems on the fringe, according to Karger, is for banks to offer safe, traditional lending practices to the poor. Several small local banks and credit unions have Todd-Karger.doc -3- come up with creative ideas allowing them to extend their services to sectors of the population that had not had access to those services previously. In order for the problems of the fringe to be more completely stamped out, however, the larger national banks will have to show the same initiative. Thus Karger does not conclude on a hopeful note. Unless millionaire bankers and CEOs learn to start hating money, the likelihood is that the poor will continue to be taken advantage of in the fringe. Todd-Karger.doc -4-