Assignment 1 Proposal – Taxation and Internet Commerce

advertisement

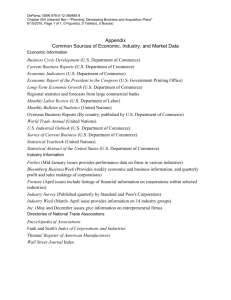

Taxation and Electronic Commerce Ross Thomas Rosst_99@yahoo.com.au Taxation and Electronic Commerce Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND AND REVIEW .................................................................................................................5 THE US EXPERIENCE ....................................................................................................................................5 1998 Internet Tax Freedom Act ...............................................................................................................5 Sales Tax, Use Tax and Nexus .................................................................................................................6 The US Retail Industry ............................................................................................................................6 THE AUSTRALIAN EXPERIENCE ....................................................................................................................7 THE UNITED KINGDOM EXPERIENCE ............................................................................................................8 THE ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT (OECD) ....................................9 CROSS-BORDER TRADE ................................................................................................................................9 OTHER PROPOSALS.....................................................................................................................................10 The UN ‘Bit Tax’ ...................................................................................................................................10 Taxing Internet Access...........................................................................................................................10 TAX COLLECTION METHODS / SOLUTIONS / SOFTWARE .............................................................................11 “The Sales Tax Clearinghouse” ............................................................................................................11 “TAXWARE” .........................................................................................................................................11 ISSUES AND CONCERNS ........................................................................................................................13 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ..........................................................................................................17 REFERENCES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .....................................................................................19 APPENDICES .............................................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. APPENDIX A – ASSIGNMENT 1 PROPOSAL ............................................ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. APPENDIX B – PRODUCT INFORMATION – THE SALES TAX CLEARINGHOUSE ......ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. APPENDIX C – PRODUCT INFORMATION – TAXWARE ........................ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Introduction The rapid growth of the Internet and of Electronic Commerce around the world can be partially attributed to the fact that, to this date, no new taxes have been applied specifically to Internetbased commerce activities. Buying a book over the Internet does not attract any extra taxes than what would normally apply if you bought that book at your local bookstore. People are generally very wary of taxation, and any announcements or imposition of new taxes are looked upon unfavourably. Consequently, quietness on the taxation front concerning the Internet has contributed to the continued growth and acceptance of the medium. However, the quietness about Internet taxation has been shattered in recent months. Governments around the world are beginning to take notice of the continued increase in Internet Commerce activities, and the potential/subsequent decrease in traditional commerce activities. As Internet Commerce becomes more widespread and accepted, the notion of ‘shopping on the net’ will gradually become just shopping. And the longer people are able to purchase goods online and not be subjected to additional taxes, or even traditional taxes in some cases, the harder it will be to change if and when tax rules are attempted to be applied to the Internet. Governments have been able to enjoy a stranglehold on the regulation of traditional commerce, and the imposition and maintenance of taxation on these activities, but this is now threatened. Governments have realised that Internet Commerce activities may actually result in some tax revenue that they are unable to collect. And what is the natural response to such an awakening? Why, “how can we tax it?” of course. The problem is that the taxation rules that apply to traditional commerce activities may not be appropriate for, or may be difficult to enforce on, Internet Commerce activities. The Internet has been traditionally subject to industry self-regulation, and excessive heavy-handedness of any Government on the Internet will not be looked upon very favourably by anyone with a vested interest in Internet Commerce (for example, merchants and consumers). The imposition of any new taxes strictly on Internet Commerce-related activities would be viewed by many as being detrimental to the future growth of Internet Commerce. 3 Taxation and Electronic Commerce In this essay I will be investigating the development and progress of the Internet Taxation issue, and discuss some of the issues and concerns that Governments are dealing with concerning the taxation of Internet Commerce. I will look at how the US, Australia, and the UK have approached Electronic Commerce, and their specific concerns about taxation. I will also identify some software solutions for the collection of sales tax on Internet-based sales, looking at their details, and the challenges faced by these companies in the current, uncertain Internet taxation climate. Also, I will look at the guidelines proposed by The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to follow in the development of taxation systems for Electronic Commerce. I will close by discussing issues and concerns identified from the areas I have researched, and also discuss the next steps for countries to take. 4 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Background and Review The US Experience 1998 Internet Tax Freedom Act In 1998 the US Congress passed the Internet Tax Freedom Act, which is an effort to control the US Government’s influence on the taxation of Internet Commerce. The Act placed a suspension on the development and imposition of any new Internet taxes until the year 2001 (Grebb, 2000, p.1). The ‘no-net-tax’ lobby groups (for example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the E-Fairness Coalition and the E-Freedom Coalition) have seen this as a small victory, but there are two main concerns about the Act. The first concern is that the Act prevents any new Internet taxes – the key word here being ‘new’. This appears to leave the door open for those in Government to extend existing tax rules to the Internet, without breaching the Act. Secondly, the freeze expires in 2001, and there is an air of uncertainty about what will happen when it expires. Senator John McCain has introduced a bill to extend the standstill on new Internet taxes indefinitely (Grebb, 2000, p.1). As a result of the Internet Tax Freedom Act, the Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce (ACEC) was appointed by Congress to develop recommendations on options for Internet Taxation, on the local, state, federal, and international levels. ACEC is investigating various issues, including how the imposition of barriers in foreign markets to US goods, services, and information engaged in Electronic Commerce will affect US consumers, US businesses trying to become established and compete in foreign markets, and the growth of the Internet as a whole. ACEC has met three times so far, and has published its recommendations. ACEC is essentially the face of the industry to the US Government, and has the ability to influence and shape any future changes to taxation, as it relates to Electronic Commerce. 5 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Sales Tax, Use Tax and Nexus In the US, there are two types of taxes that must be paid by consumers on purchases that they make. The first is sales tax, which generally is added to the purchase price of the good, and remitted to the appropriate authorities by the vendor, on behalf of the consumer. The second tax is known as use tax, which is defined as ‘…a tax imposed by states to collect taxes on sales which do not take place in their state. The tax is meant to ensure that all purchases are taxed, whether purchased locally or from out of state sellers” (The Sales Tax Clearinghouse, 1999 – 2000, p.1). It is up to the consumer to pay the use tax and remit the details, after the purchase has been made. Not many people, if any at all, comply with this tax, and the US Government has put in little, if any, effort to enforce this. In effect, use tax is supposed to be paid when you buy goods outside your state, and is supposed to supplement the sales tax not collected due to the company not having a nexus in the consumers home state. Consequently, the question being asked is should consumers who buy goods online be subjected to the same use tax rules, given the largely ungoverned usage of this law? Nexus refers to a physical presence, and companies in the US are not obliged to collect sales tax made on sales in states where the company does not have a nexus. This law is the result of a US Supreme Court decision in 1992 (Quill v. North Dakota), and applies across the board, including the areas of catalogue / mail order sales, and Internet sites (Wolverton and Macavinta, 1999, p.2). The nexus issue has one main loophole, which we will visit further in this report. The US Retail Industry The retail industry in the United States is especially interested in the taxation of Internet Commerce activities, and is one of the most vocal groups involved in the current discussions in the US about this issue. Their concern is that traditional, ‘main street’ retailers rely solely on sales made through their stores, and must consequently inflate their prices to include the sales tax component that must be paid. For example, if you were to purchase a book from a book store in New York, the price you pay would include the sales tax applicable in that state. However, if you were to log on to the Amazan.com site, and purchase the same book, the price you pay would not 6 Taxation and Electronic Commerce include the sales tax component, and therefore be cheaper and more attractive to purchase online rather at the ‘main street’ store. The National Retail Foundation (NRF) in the US has taken the position that ‘merchandise sold on the Internet should be taxed just the same as items sold in “brick-and-mortar” stores (Krebb, 2000, p.1). NRF members believe that a tax-free Internet would assist its members that have ecommerce businesses, hurt their ‘main street’ members, and be a mixture of good and bad for businesses with both physical and online commerce activities. Consequently, the NRF is actively pursuing this topic, and have taken the stance described above, in order to reduce inequities across the retail (and e-tail) industry. The Australian Experience Australia is currently undergoing massive taxation reform, which includes the abolition of several existing taxes, and the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax. The timing of this tax reform process in Australia could not be better from an Electronic Commerce perspective. Many of the issues regarding taxation of Electronic Commerce are being investigated and considered by the Government as they move along the tax reform road. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has produced two discussion papers on Electronic Commerce and taxation, being 1) Tax and the Internet (1997), and 2) Tax and the Internet Second Report (December 1999). Many other countries have been performing similar investigations, and producing similar reports, but not many are currently undergoing the process of tax reform themselves. Therefore, Australia is poised to become a forerunner in the implementation of taxation changes to prepare for the everevolving electronic economy, provided the opportunity is grasped and used wisely, and any decisions (about taxation and Electronic Commerce) are made carefully. During 1997-98, the Australian Customs Service collected over $3.7 billion in duty/sales tax on imports (DFAT(1), 1999, p.178). Customs is the second largest collector of commonwealth revenue, behind the ATO. The increasing popularity of Electronic Commerce in Australia, and the subsequent increase in imports of goods from overseas, has seen the Customs Service and the ATO work jointly to monitor these imports, and assess the (potential) impacts on their tax revenue base. Additionally, the increase in trade volumes from Electronic Commerce activities is also being monitored, to identify any effects on Customs processing ability. 7 Taxation and Electronic Commerce So far, the volume of additional trade generated from the Internet ‘…has not reached levels that impinge significantly on the efficiency or effectiveness of Australian Customs procedures’ (DFAT(1), 1999, p.180). However, it is perceived that if the trend of low value imports continues to increase, some impacts on Customs resources would begin to be felt. Popular ‘goods’ that are downloaded from the Internet, such as music and software, are not seen as ‘goods’ under the Customs Act, and therefore no duty is collectible by the Customs Service on the import of these. The Australian Government in December 1997 announced a new tax exemption for goods delivered (ie downloaded) via the Internet (Lawrence, E., Corbitt, Tidwell, Fisher, and Lawrence, J.R., 1998, p.176), which was viewed as a positive decision by the industry. The United Kingdom Experience In recent discussions concerning reform of the taxation system, the United Kingdom Government has included Electronic Commerce as a major topic for discussion, and an influencing factor in any proposed reform. The Government believes that the following basic principles must be applied to the taxation of Electronic Commerce: neutrality, certainty, transparency, effectiveness, and efficiency (Russell, D. (Year unknown), p. 2). These principles should be abided by in order to ensure that taxation will not prevent the growth of Electronic Commerce, and that “tax rules and compliance in the area should be neutral between e-commerce and other more traditional forms of commerce, but tax revenue should remain secure.” (Russell, D. (Year unknown), p. 1). However, the UK Government do share some familiar concerns about the taxation, and the new Internet economy. These include: (Russell, D. (Year unknown), p. 4) the possibility to trade for short periods on the Internet without informing tax authorities, the ease of moving assets offshore, the exploitation of low-tax jurisdictions, and the anonymity of electronic money. These are fairly standard concerns that are shared in general by the many other countries cross the globe, who are also looking at the potential impacts Electronic Commerce might have on their own tax revenue bases. 8 Taxation and Electronic Commerce The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) The principles the UK Government have adopted are in line with the guidelines presented by the OECD in their “Electronic Commerce: Taxation Framework Decisions” paper. In this paper, the OECD identified the following taxation principles that should apply to Electronic Commerce (OECD, pp5, 6): 1) Neutrality – taxation should be neutral and equitable between conventional and electronic forms of commerce. 2) Efficiency – compliance and administrative costs for taxpayers and authorities should be minimised where possible. 3) Certainty and simplicity – tax rules should be simple to understand by the taxpayers, so they are aware of what to expect in their transactions. 4) Effectiveness and Fairness – the right amount of tax should be produced at the right time, and tax avoidance/evasion potential should be minimised. 5) Flexibility – the taxation systems should be adaptable to keep up with changes. These principles are clear, simple guidelines that Governments are encouraged to utilise in the development of their taxation policies for Electronic Commerce activities. These guidelines can be applied to conventional taxation systems as well, not just the applicability to Internet-based sales. Research has uncovered that all of the US, Australian, and the UK Governments have chosen to follow these guidelines, in one form or another (DFAT(2), 1999, p.189). The guidelines provide the base for the development of an equitable taxation system which will encourage the growth of Electronic Commerce, whilst ensuring the appropriate levels of tax revenue can be collected to provide the necessary life services to citizens. Cross-Border Trade Cross-Border Trade has always been an issue for Governments around the world. Primarily, Governments want to protect their local industries, and the import of goods from overseas presents a threat to local industry. Consequently, Governments have elected in the past to develop and impose customs duties on imports, in order to make the import less attractive than purchasing locally, and also to act as an additional boost to taxation revenue for the Government. 9 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Such customs duties have been viewed as a major hindrance to the development of international, cross-border trade. However, the appearance and evolution of Electronic Commerce has presented a major opportunity to assist the growth of international trade. Obviously, Governments still need to protect their local industries, and protect their tax revenue base, but they are aware they must not be overly restrictive in the area of Electronic Commerce. As a result, no country currently imposes duties on electronic transmissions (Abelson, 1999, p.1). Other Proposals The UN ‘Bit Tax’ In July 1999, the United Nations Development Programme released a report (the Human Development Report 1999) in which it recommended the Internet be subjected to taxation in order to help underdeveloped countries get access to the Internet. The suggestion by the UN is a ‘bit tax’, which they envision being a ‘tax of one US cent on every 100 lengthy emails’ (Reducing the Gap, 1999). The UN state that this ‘bit tax’ would generate al least $70 billion per year, which would be more than enough to provide the necessary funding for developing countries to keep up with the Internet revolution. Not surprisingly, industry experts and the ‘no-net-tax’ lobby groups have met this proposal with outcry. Such a tax would be a large burden to the Internet, and would seriously impede the progress of its development and usage across the globe. The key question to be asked here is which organisation or body would be the enforcer of such a tax, as the UN has expressed its desire not to be so. If there was one central agency responsible for the monitoring and enforcement of such a strict policy, who would monitor them to ensure they did not abuse their position of power, and misuse the confidential and private information contained in the e-mail messages? Perhaps as a sign of the unpopularity of this proposal, the ‘bit tax’ does not currently appear on anybody’s Electronic Commerce taxation agenda. Taxing Internet Access The US, Australian, and UK Governments have each discussed this issue, and have arrived at the same conclusion – that it would be detrimental to the growth of Electronic Commerce and the 10 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Internet in general, if any new taxes were imposed on Internet access. The Australian Government announced its stance on the issue in December 1997, by vowing not to introduce a tax on Internet access (Lawrence, et al, 1998, p. 176). It is widely recognised that a tax on Internet access would hinder the adoption of Electronic Commerce across the globe, and the growth of the Internet would slow down markedly. Tax Collection Methods / Solutions / Software “The Sales Tax Clearinghouse” The Sales Tax Clearinghouse (STC) is an American company that provides software to online merchants that computes the taxes applicable to online purchases, which integrates with the merchant’s existing business system. Additionally, STC provides merchants with a complete range of compliance services, from licensing to filing and remitting, performed by STC on the merchant’s behalf. Before a customer’s online purchase is finalised, the STC’s TaxCalc module is called by the merchant’s business system to calculate the sales and use taxes applicable to the order. These taxes are then added to the order, so the customer can complete it. The tax calculations are performed in real time, ‘…with an SSL connection to our high-speed, secure servers so the results are always 100% current and accurate’ (The Sales Tax Clearinghouse, 1999 – 2000, p.1). STC then collates all of a merchant’s transactions, in order to determine the amount of tax to remit to each of 6,000 tax authorities across the US, completes the appropriate forms and performs the actual remittance on behalf of the merchant. The merchant is able to logon to the STC’s website to examine all past and pending transactions and transfers. “TAXWARE” Another US company with sales tax collection software is Taxware International, Inc. Taxware has three major tax software systems, being – 1) the Sales/Use Tax System, 2) the Internet Tax System, and 3) the WorldTax System. The Internet Tax System is the interesting offering of Taxware, in the context of this paper. The Internet Tax System has been developed to calculate the appropriate sales, use, and international tax for online sales transactions. Web merchants have 11 Taxation and Electronic Commerce the option to use Taxware as a service bureau, where the merchant’s server passes the transaction information to the Taxware server, where the appropriate calculations are performed, and the resultant figures sent back to the merchant’s server. After the purchase has been made, the software can review the sale according to various sales and use tax data, including ‘…customer exemptions, product taxability, and geographical jurisdictions’ (TAXWARE, 1999, p. 2). The sales tax amount for the transaction is calculated, and the system records all the tax information of the transaction, to ensure the merchant is compliant with their tax legislation, and also to enable management reporting on the transactions. The whole process is transparent to the customer; they do not even know the complexity behind the sale. The system also features a “Product Taxability Matrix”, which provides the ability to track a large number of product categories in the internationally, and to incorporate information on varying tax rates in countries, states, counties, and cities. These are just two companies at the forefront of developing and providing comprehensive solutions to the challenges posed by Electronic Commerce and the associated taxation challenges. These solutions cover all aspects of taxation, (especially for the US as this is the companies base) including international taxation complexities as well. It is no longer a question of if, rather a question of when and how taxes will be applied to Internet based sales, and these companies are well poised to dominate the market with their solutions. However, these companies are faced with significant challenges to keep their products up to date with any future changes to tax rules implemented by the US Government (and other international Governments), and to rollout the changes to their installed customer base. 12 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Issues and Concerns Ernst and Young released a report in 1999 (The Sky Is Not Falling: Why State and Local Revenues Were Not Significantly Impacted By the Internet in 1998) that investigates the impact of Electronic Commerce on state and local revenues in the US, for 1998. Two key findings of this report demonstrate the relative infancy of Electronic Commerce, and the minimal impact it has had on tax revenues, in that: 1. Business to Consumer (B2C) sales over the Internet in 1998 totalled approximately US$20 billion, which represents ‘less than three tenths of one percent of total consumer spending’ for that year; and (Cline, 1999, p. i) 2. The sales and use tax not collected from these sales across the Internet totalled less than US$170 million, which represents ‘one tenth of one percent of total state and local Government sales and use tax collections’. (Cline, 1999, p. i) Additionally, Ernst and Young found in their report that approximately ’63 percent of current Electronic Commerce business-to-consumer sales are intangible services’…’or exempt products…not subject to state and local sales and use taxes’. (Cline, 1999, p. ii) These figures put the impact of Electronic Commerce on tax revenues in perspective, as in this year (1998) the figures were relatively small. However, Governments are fearful that the continual shift of commerce activities to the Internet will have a much greater impact on their tax revenues in the years to come. This is a valid concern, and the challenge at hand is to (re) design the taxation methods for Electronic Commerce activities (and perhaps traditional commerce methods also) in order to ensure consistency and a balance between the two. It is worth noting that these figures were based on the research of the Electronic Commerce activities in 1998. This was the year the Internet Tax Freedom Act was introduced, and also the first big year for business-to-consumer Electronic Commerce activities. In the years since then, the dollar amounts of Electronic Commerce activities have increased substantially, and we are now in a position where the Act’s moratorium expires in approximately one year’s time. Supporters of taxing Internet-based sales activities can simply extrapolate these figures to be based on more current B2C sales over the Internet figures, which might add more weight to their argument, as no doubt they would be somewhat inflated from the 1998 figures. 13 Taxation and Electronic Commerce The retail industry in the US has seen some interesting developments by companies with both a traditional ‘Main Street’ presence, and an online presence. Some companies have elected to ‘spinoff’ the on-line component of their business into a new, stand alone company. Wal-Mart is one example of a company that has done this (Bloomberg, 2000). Wal-Mart has created a new company, Wal-Mart.com, which is solely responsible for Wal-Mart’s Internet sales operations. Wal-Mart is not the only company to make such a move, with Barnes and Noble making a similar business decision. The reasoning behind this move is Wal-Mart has stores in more than 2000 locations across the US. Due to such market reach, it is fairly safe to say that Wal-Mart would have to collect sales tax on just about every sale made online to anywhere in the US, due to the nexus reasoning. However, Wal-Mart.com will have a nexus, or presence, in only three states – California, Arkansas, and Utah. This greatly reduces the number of states and local Governments Wal-Mart will be required to collect sales taxes for. The Ernst and Young study reported that ‘for companies that must collect sales tax in multiple jurisdictions, the collection costs can be as high as 87 percent of taxes collected’ (Bloomberg, 2000). It can therefore be presumed that Wal-Mart stands to make considerable savings on the reduction in sales tax collection requirements through its online arm. By creating an online branch for Internet sales, companies have the ability to seek out the states with the most lenient sales tax rules, and elect to base their operations there. The EY report also states that although ‘… out-of-state sellers without physical nexus have no legal obligation to collect sales and use tax from in-state consumers, the in-state consumers still have a use tax liability. The potential erosion of tax collections is due to lack of effective enforcement of the existing use tax by state and local Governments’ (Cline, 1999, p. 16). This identifies where the potential tax shortfall will arise from – the use tax collections (or lack thereof). The US Government will need to radically redefine how the use tax system operates, or perhaps even abolish it and replace it with something more enforceable, to ensure adequate inflows of tax revenue in the future. However, it must be ensured that the traditional, ‘main street’ retail organisations are not disadvantaged by taxation changes and applicability to the Internet, in order to keep in line with the OECD taxation principle of neutrality. 14 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Latrobe University undertook a study in 1997 on Electronic Commerce ant the Australian Taxation System, and researched the potential areas of concern across six industries: Computer Software, News and Information, Recorded Music, Gambling, Travel, and Retail Goods. In the News and Information Industry, it was found that a considerable movement of advertising to the Internet from traditional print media could possibly lead to a decline in newspaper and magazine production, due to the loss of revenue from the advertising. This could lead to a reduction in the amount of sales tax that could be collected from the sales of newspapers and magazines. Therefore there lies the potential for some erosion of the Australian tax base, because sales tax currently being paid on paper would not be replaced with a new sales tax on inputs to electronic publication. The other major industry in Australia to be affected by Electronic Commerce is the Retail Goods industry. The report states that ‘at the applicable sales tax rate of 22%, Australia stands to lose $132 million of sales tax if all paper catalogues were to be turned into untaxed, electronically distributed information distributed on the World Wide Web (Richardson and White, 1997, p. 15). Therefore, there would be some erosion of the tax base from this industry as traditional goods and services move from a ‘taxable form and become an untaxed electronic service’ (Richardson and White, 1997, p. 16). However, the report also states that a major barrier to the adoption of Electronic Commerce in Australia in the Retail Goods industry is the need of consumers to be able to touch and feel the goods prior to a purchase being committed. One of the most attractive features of using the Internet is that it is essentially ‘free’, making it accessible to people even in the most remote regions. Any attempt to tax Internet access would no doubt see growth come to a standstill in developing nations, as they simply would not be able to afford to be a part of it. So far, taxing access has not been on Government’s agendas, but one technological advance that may see this change is the increasing usage of the Internet for traditional ‘voice’ calls (ie phone calls over IP), as this may impact tax revenue Governments now collect from telecommunications carriers. It is widely recognised that excessive taxation or regulation of the Internet would harm rather then foster to continued growth of the medium. The Australian Government has recognised that it ‘…must continue to resist measures that might damage Internet commerce, such as imposing taxes that distort the balance between online and offline trading, and developing and imposing 15 Taxation and Electronic Commerce uniform technical standards for Internet commerce.’ (DFAT(1), 1999, p.42). However, it is also recognised that the Government should leave national and international standards ‘…to the market to sort out, with the caveat that Governments have a role ensuring that standards are useful and are not disguised non tariff barriers.’ (DFAT(1), 1999, p.42). The Government must be involved in the discussions about taxing Electronic Commerce, but the industry is in a more useful position to prepare the guidelines and proposals. This is similar to the self-regulation of the telecommunications industry, where codes of practice are developed by industry bodies, and presented to the Government regulators for approval. Of course, with taxation, the Government has the final say in what laws are imposed, but the industry can provide valuable input nonetheless. An important area that the Australian Government needs to work on is producing laws and standards for digital signatures. Digital signatures are seen as an essential building block to the adoption of Electronic Commerce for international trade, along with the development of crossborder treaties. Standards for digital signatures must be developed, presented, and accepted by the international community, as the ‘mutual recognition of electronic signatures by various countries would foster international Internet commerce’ (DFAT(1), 1999, p.286). Clearly defined taxation rules and obligations, along with uniform protocols and requirements for digital signatures, will assist the growth and popularity of using the Internet and Electronic Commerce for international trade. The issue of ‘who collects what tax’ from cross-border transactions is a major concern to many Governments, and Australia ‘needs to actively participate in international forums on this topic; the aim should be to preserve fairness and build international cooperation to police firms which flout agreed commercial standards of behaviour.’ (DFAT(1), 1999, p.369). The clarification of this issue, by close working relationships between Governments, will help Electronic Commerce flourish across the international community, as the tax questions will be resolved, and participants will be able to enter into a transaction, with full knowledge of the tax implications of the transaction. 16 Taxation and Electronic Commerce Summary and Conclusions I strongly agree with the principles for taxation that the OECD has put forward. These principles allow for an equitable tax system, which is fair to both the Government’s requirement for tax revenue and also fair to the taxpayers as well. The other issue the OECD principles would assist in resolving is in ensuring that both retail and e-tail organisations are treated equitably. I believe there is no justifiable case for e-tail organisations to be treated more favourably with taxation rules than traditional retail organisations. A common definition of ‘nexus’ for all forms of commerce (be it ‘main street’ or Electronic Commerce) must be determined in the US to remove the confusion on this issue. For the US, I see there being the need for national reform of the taxation system, across all states, to reduce the imbalance in sales tax rates and collection rules. This may even result in the federal Government providing some form of ‘sponsorship’ to smaller states that may be more heavily impacted by any tax reform. A common sales tax rate, across all states, and across all forms of sales, would provide an equal base for commerce and e-commerce across the US. Considering that the use tax is not widely enforced, this could be abolished, and the sales tax rates inflated accordingly to include this. I believe that the answer to the taxation of Electronic Commerce does not lie in new taxes, but rather tax reform. Reform of the current tax system, without singling out taxing Electronic Commerce activities (but of course including Electronic Commerce in any proposals/reform), would be the fairest way to introduce equalities to the tax system, for taxpayers and for the Government. The outcomes of the ACEC discussions in March will be interesting to take notice of. The moratorium on new Internet taxes is rapidly approaching its expiration, and the industry is now beginning to take notice of this. Questions of ‘what will happen next’ are beginning to be asked, and a clear path must be laid put by ACEC. This will then have flow on impacts or at least influence to how other countries around the world decide how to tax Electronic Commerce. I believe that the Electronic Commerce activities will be taxed in the future, and I am hopeful that the decision-makers will ensure that this is fair for all parties involved. Taxation and Electronic Commerce is a very large area, covering local, state, federal, and international levels, it is in the best interests of all countries to actively participate in discussions around this issue. 17 Taxation and Electronic Commerce One of the major difficulties is ensuring any legislation, standards, and/or new taxes developed are consistent across all countries around the globe. The Internet has created a truly global marketplace, penetrating even the smallest countries in the world. The US is at the forefront of confronting the issue, however the global community must be careful that the US rules and standards do not become the defacto industry standard, if they do not meet their specific requirements. Tax rules implemented by Australia and other countries around the world for ecommerce activities must be neutral with other traditional commerce activities. This is to ensure that taxation is not seen as a hindrance to e-commerce, but also to ensure that tax revenue does not lose out. Over the next few years, Electronic Commerce and the Internet will no longer be a curiosity, but an integral part of a business’s strategies, and many traditional commerce activities will have been migrated to the Internet. Governments, practitioners, and key industry players will need to come together to deal with the consequences of this shift of business to the Internet. If Governments are not involved, they will be the losers, as their tax revenue base will certainly be reduced, and increased cross border trade through the Internet may blur the lines of control a country’s Government currently has. Developing, implementing, and ensuring this balance is the challenge faced today, and action must be taken fast, as this is already a reality. 18 Taxation and Electronic Commerce References and Acknowledgments Abelson, D. (1999, Jun. 22). Duty-Free Cyberspace: What It Means, Why It Is Important. Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce [Online]. Available: http://www.ecommercecommission.org/document/DonAbelson.doc (1999, Jun. 22). Bloomberg News. (2000, Jan. 07). Wal-Mart’s Net spin-off to provide tax relief. Cnet News.com [Online]. Available: http://news.cnet.com/news/0-1007-202-1518612.html (2000, Jan. 07). Cline, R.J., and Neubig, T.S. (1999, Jun. 18). The Sky Is Not Falling: Why State and Local Revenues Were Not Significantly Impacted By the Internet in 1998. DFAT(1) (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). (1999, Feb. 12). Driving Forces on the New Silk Road: The use of Electronic Commerce by Australian business. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade [Online]. Available: http://www.dfat.gov.au/nsr/driving.pdf (1999, Feb. 12). DFAT(2) (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). (1999, Feb. 12). Creating a Clearway on the New Silk Road. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade [Online]. Available: http://www.dfat.gov.au/nsr/clearway.pdf (1999, Feb. 12). Grebb, M. (2000, Feb.). The Taxman Cometh. Business 2.0 [Online]. Available: http://www.business2.com/articles/2000/02/text/nettaxes.html (2000, February). Human Development Report 1999 – Reducing the Gap Between the Knows and the Know-Nots. (1999, Jul. 12). United Nations Development Programme [Online]. Available: http://www.undp.org/hdro/E3.html (1999, Jul. 12). Krebbs, B. (2000, Jan. 21). Retail Organization Backs Internet Taxes. eMarketer [Online]. Available: http://www.emarketer.com/enews/012400_itax.html (2000, Jan. 21). Lawrence, E., Corbitt, B., Tidwell, A., Fisher, J., and Lawrence, J.R. (1998). Internet Commerce: Digital Models for Business. Milton, Qld, Australia: John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd. 19 Taxation and Electronic Commerce OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (1998, Oct. 08). Electronic Commerce: Taxation Framework Conditions. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [Online]. Available: http://www.oecd.org//daf/fa/e_com/framewke.pdf (1998, Oct. 08). Russell, D. (Year unknown). Electronic Commerce – the United Kingdom’s Taxation Agenda. BNA International, Inc., London. Richardson, C.L., and White, P. B. (1997, Aug. 04). Electronic Commerce and the Australian Taxation System: An exploratory study of six industries. Australian Taxation Office [Online]. Available: http://www.ato.gov.au/content.asp?doc=/content/Businesses/ecommerce_Latrobun.htm (1997, Aug. 04). TAXWARE. (1999). Internet Tax System. TAXWARE – Internet Tax System [Online]. Available: http://www.taxware.com/Zproducts/Internet/Internet.htm (1999). The Sales Tax Clearinghouse. (1999 - 2000). Products and Services. The Sales Tax Clearinghouse [Online]. Available: http://www.thestc.com/Services.stm (1999 - 2000). Wolverton, T., Macavinta, C. (1999, Dec. 14). E-commerce Commission Struggles With Sales Tax Decision. Cnet News.com [Online]. Available: http://news.cnet.com/news/0-1007-202-1495393.html (1999, Dec. 14). 20 Taxation and Electronic Commerce 21